5 Heroes of Vig – Dobraç,

More on Albania ……

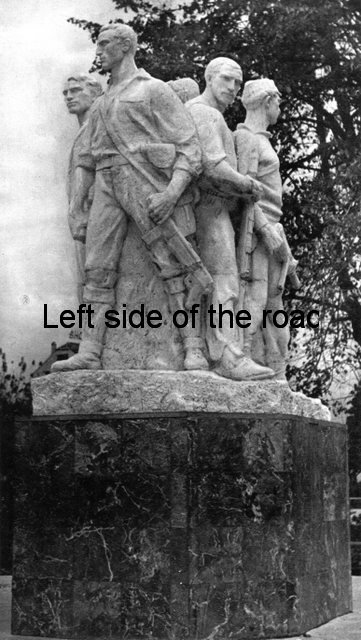

Five Heroes of Vig – Skhodër

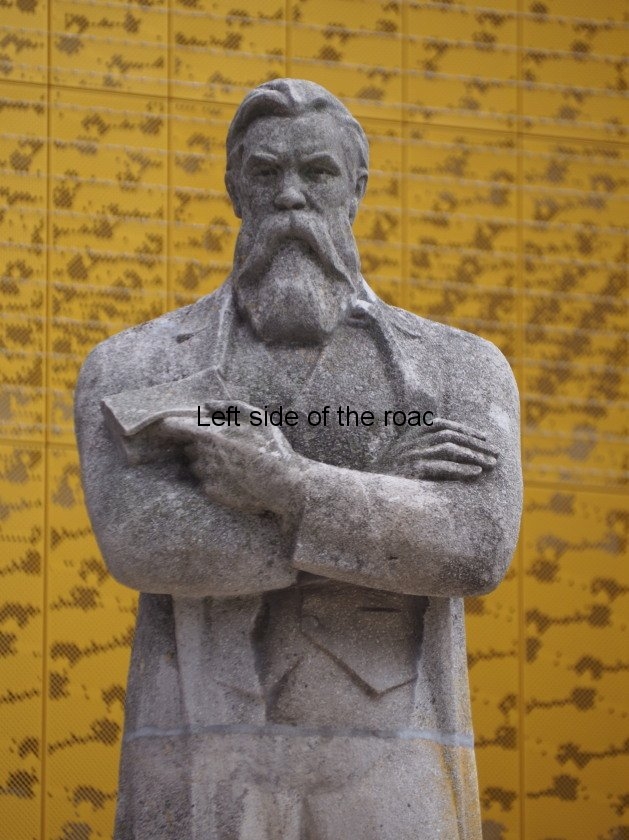

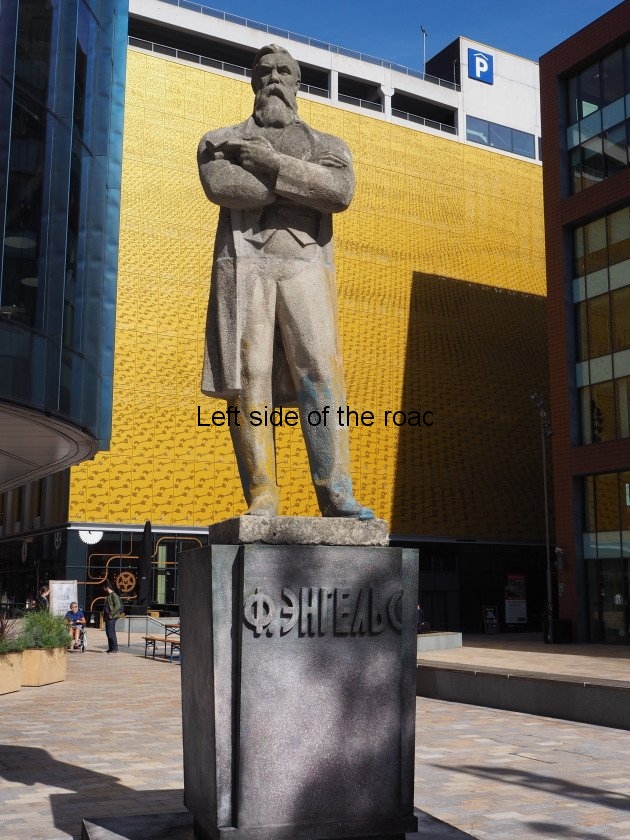

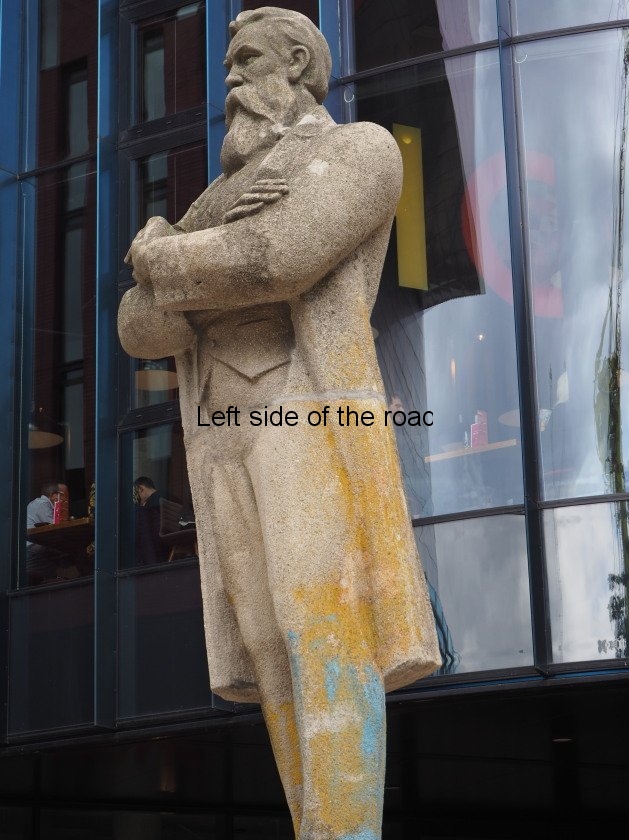

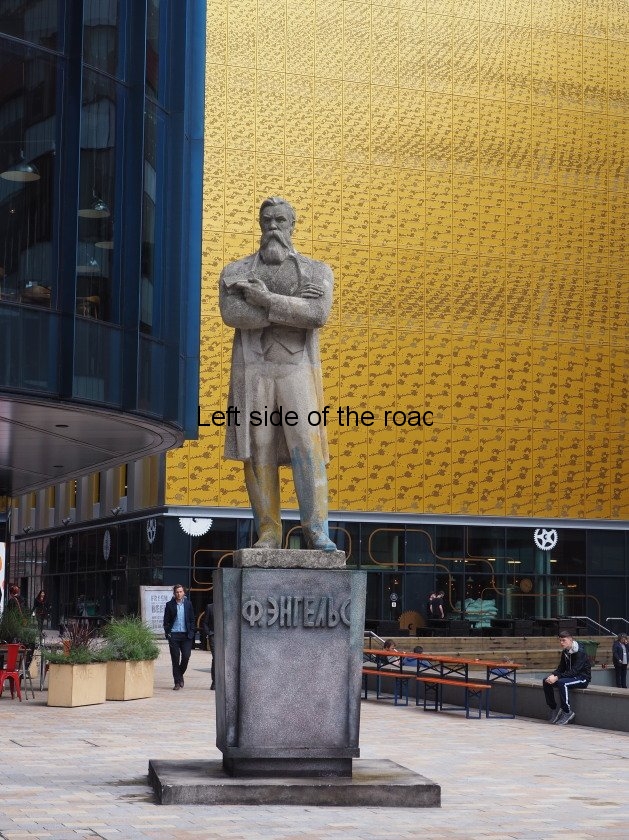

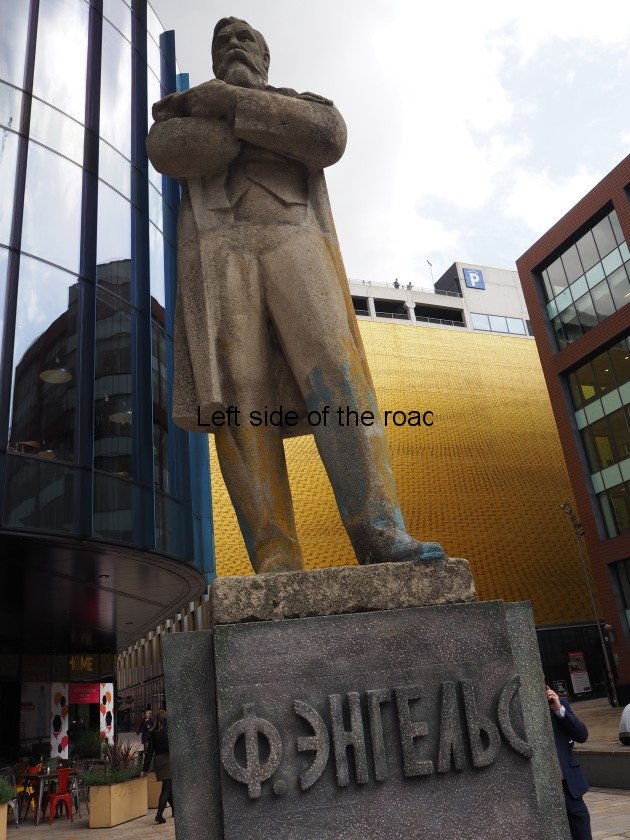

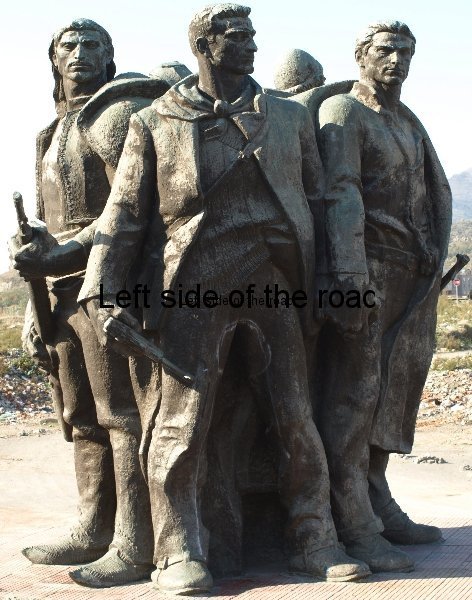

Celebrating solidarity and the willingness towards self-sacrifice in the common cause the statue of the Five Heroes of Vig once stood in one of the central squares of Skhodër, in northern Albania. After a period ‘out in the wilderness’ – close to the city rubbish dump and subject to crass, petty thievery it has now found a new permanent home in the centre of a roundabout to the north of the city.

The statue commemorates events that took place in the small village of Vig in 1944, just before the victory of the Partisans over the Germany Fascists, their hangers-on, collaborators and lackeys.

On August 21, 1944, at Vig in the Mirdita highlands, 5 long time partisans went to talk to the peasants who were under the thumb of the feudal chief, Gjon Markagjoni, ‘a tool of the fascist occupiers’.

5 heroes of vig

From left to right: Ndoc Dedo (Teli), Ndoc Mazi (Minuku), Naim Gjylbegu (Besniku), Hidajet Lezha (Hida), Ahmet Haxhia (Tigri).

Informers let the fascists know of their whereabouts and 200 Nazi troops were sent to capture or kill the five. The fight went on for 6 hours, the Communists fighting to the last bullet, and all of them being killed.

5 Heroes of Vig – Pandi Mele

The incident was depicted in an Albanian film of 1982 called Besa e Kuqe (Red Faith), directed by Pirro Milkani.

Ahmet Haxhia 1926-1944

Nom de guerre Tigri (Tiger). From a lower middle class family from Skhodër. Joined the Albanian Communist Party at the beginning of 1943 and worked in the town as part of the organising resistance amongst young people. In December of that year joined the Partisan unit based in the Miradita region. The youngest of the five.

Hydajet Lezha 1920-1944

Nom de guerre Hida. Born in the town of Lezha. Joined the Albanian Communist Party in early 1943 and, as an orphan, it was here where he found his true family.

Naim Gjylbegu 1920-1944

Nom de guerre Besniku (Faithful). Was involved in the Skhodër Communist Group, the forerunner of the Albanian Communist Party, when still in his teens. In October 1942 became a member of the regional Committee of Communist Youth. Soon after arrested and tortured for his activities but once released became commander of the local CETA – guerrilla organisation.

Ndoc Deda 1918-1944

Nom de guerre Teli (Wire). Born in a village in the Milot region into a peasant family. Organised revolutionary activity in the ranks of the old army later leaving to join the Partisans in the middle of 1943 and in October of that year joined the Albanian Communist Party.

Ndoc Mazi 1920-1944

Nom de guerre Minuku. Was born into a poor working class family in Skhodër. Was a member of the Skhodër Communist Group before it morphed into the Albanian Communist Party, Suffered from tuberculosis but still worked underground in, first, Durrës and later in Skhodër before joining the Partisan army in the Mirdita region.

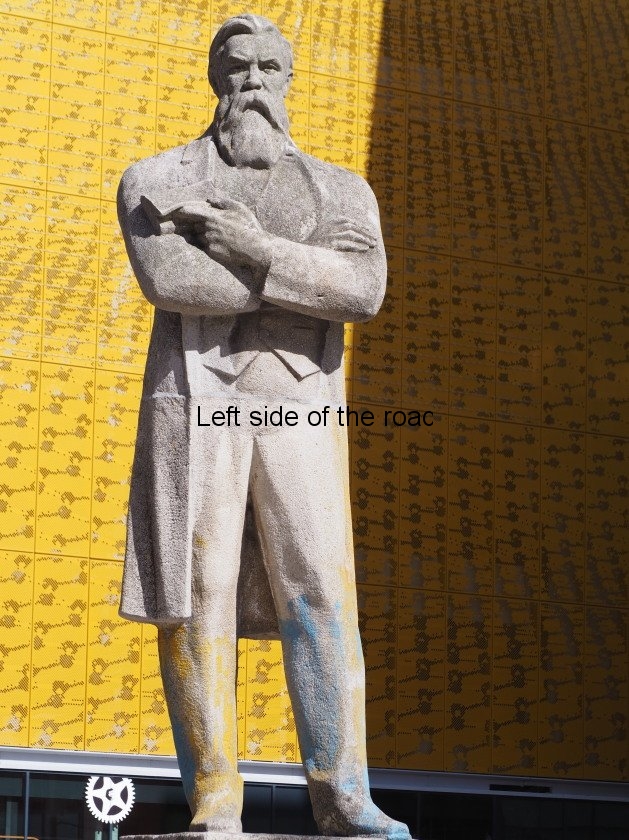

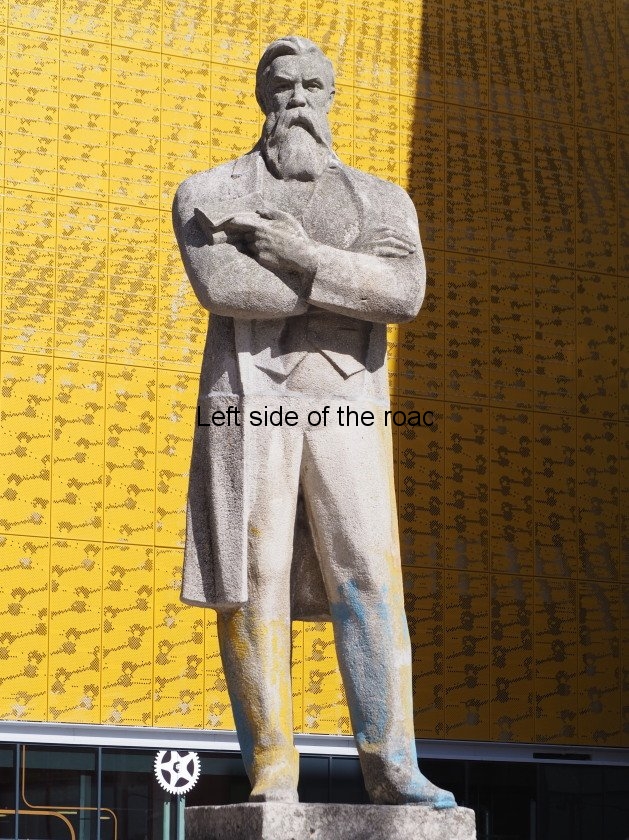

The statue, whose name in Albanian is ‘Monumenti i Heronjve të Vigut’, is the work of Shaban Hadëri (28th March 1928 – 14th January 2010) who created the statue of Isa Boletini – also in Shkodër – and collaborated on two of the most important existing monumental statues in Albania – Mother Albania, in the National Martyrs’ Cemetery in Tirana, and the Independence Memorial in the city of Vlorë.

Hadëri joined the Partisan resistance to the Fascist invasion at the age of sixteen in 1944 and was able to follow his artistic education following the success of that war of liberation and the opportunities the Communists provided in terms of education.

This statue has gone through good times and bad. It originally started out as a concrete statue, of a little more than life-size, and was installed in the square beside the Rozafa Hotel in the centre of Shkodër in 1969.

5 Heroes of Vig in concrete

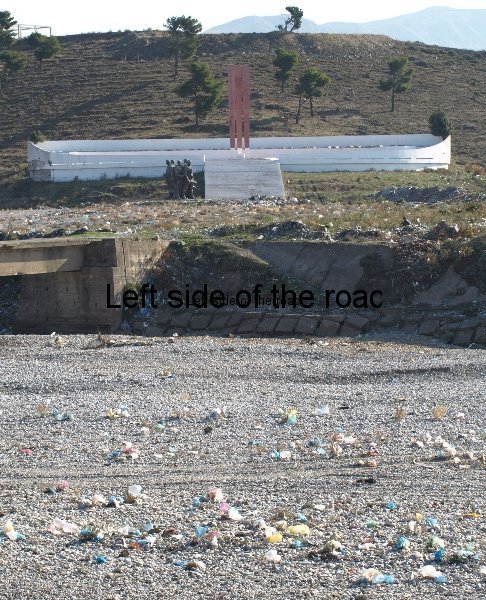

This original was replaced by a much larger, 5 metres high, statue of bronze. This new statue was similar, with the same idea as the original, but with a few differences. This was mainly in the form of dress and the way they carried their armaments. It remained there until 31st January 2009. On that date it was transported to a site beside the Martyrs’ Cemetery on the banks of the River Kir.

5 Heroes of Vig – Shkoder

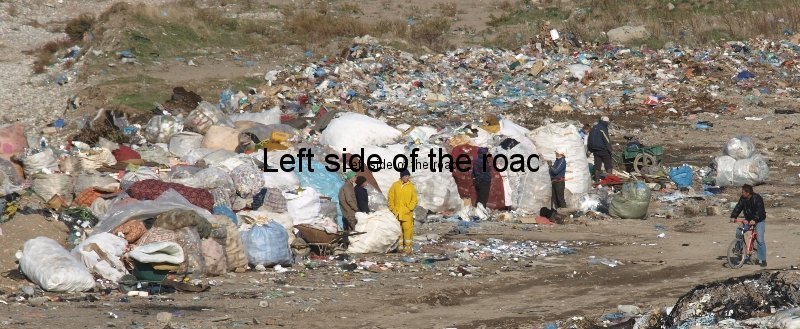

When this cemetery was established the location would have been enviable – outside of the city, close to a river and with the mountains of the Dukagjin highlands behind it. However, since the arrival of ‘democracy’ in the 1990s many things have changed. The river, which only has significant water just after the snow melts in the spring, is now a tragic site.

The town’s rubbish dump has been created beside the river, very close to the Martyrs’ Cemetery. One of the results of the greater availability of consumer goods has been a massive explosion in the number of plastic bags. Once they are just dumped in the open air (there’s no attempt at a landfill in Shkodër) all it takes is a light breeze and the bags are everywhere. OK if you like your river beds multicoloured but generally disastrous for the environment.

Rubbish in Kir River

Another legacy of the re-introduction of capitalism is the job of sifting through rubbish dumps, a trade that now spans the globe where, on some of the huge dumps, people both live and work on the detritus of others. At the Shkodër dump there are small groups bagging up whatever there might be of value and now they are really the only ones who visit the area in any frequency.

I’m assuming it must have been someone amongst this group that decided, at the end of 2012, that there was monetary value in the bronze statue of the 5 heroes and have been helping themselves to bits of it. There were certain amongst the politicians of Shkodër city council who, I’m sure, were glad of this news, that being part of their plan in the first place. In the centre of town any vandalism would be obvious but outside in a totally unpopulated area anything could, and did, happen.

This is what you would expect from a council that has changed the name of the road to the railway station to ‘Hungarian Anti-Communist Revolution Road’ as well as pandering to the US with celebrating nationals of that country who have had nothing to do with Albania apart from trying to make it a vassal to a greater imperialist power either in the distant or recent past. It’s in such a fundamentalist Catholic environment that Mother Teresa appears everywhere and the anti-Communist paintings have been commissioned in the Franciscan Church.

The present day ‘so-called’ Socialist Party made noises about the destruction of national heritage and that this showed a total lack of respect for those who had fought for the country’s liberation from Fascism. Despite their silence in the past – when such desecration has occurred and their almost non-existent opposition to the return of Ahmed Zogu’s remains to Tirana in November 2012 – their efforts have resulted in the re-siting of the (cleaned up if not renovated statue) on the northern perimeter of the city.

The Statue

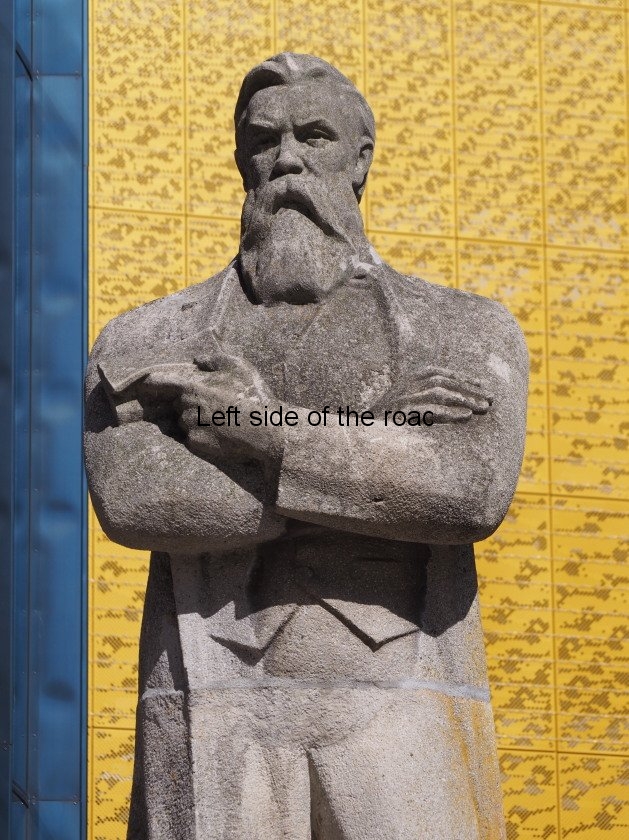

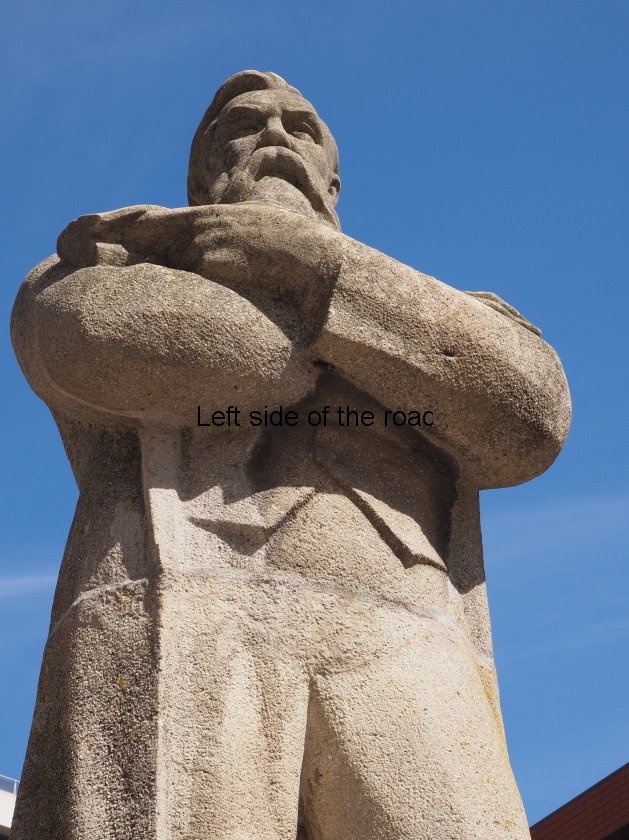

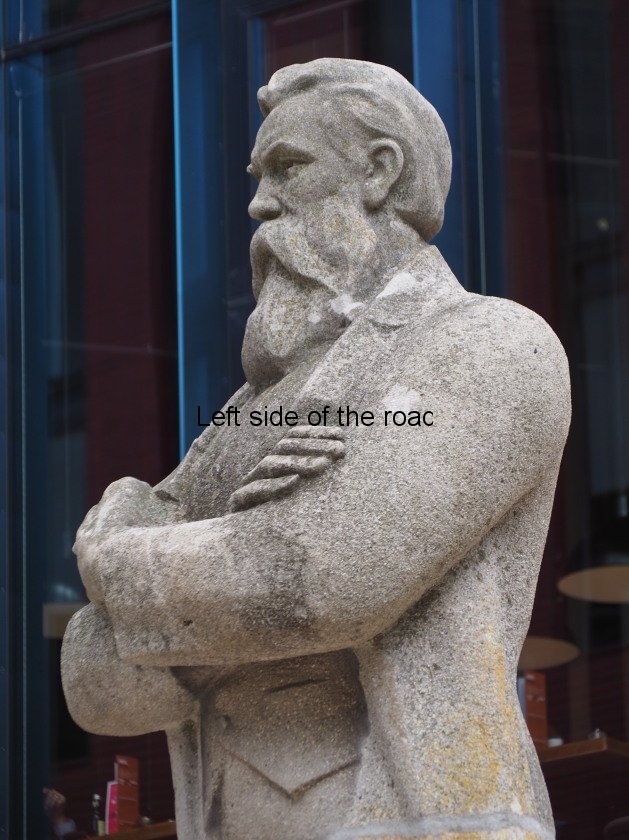

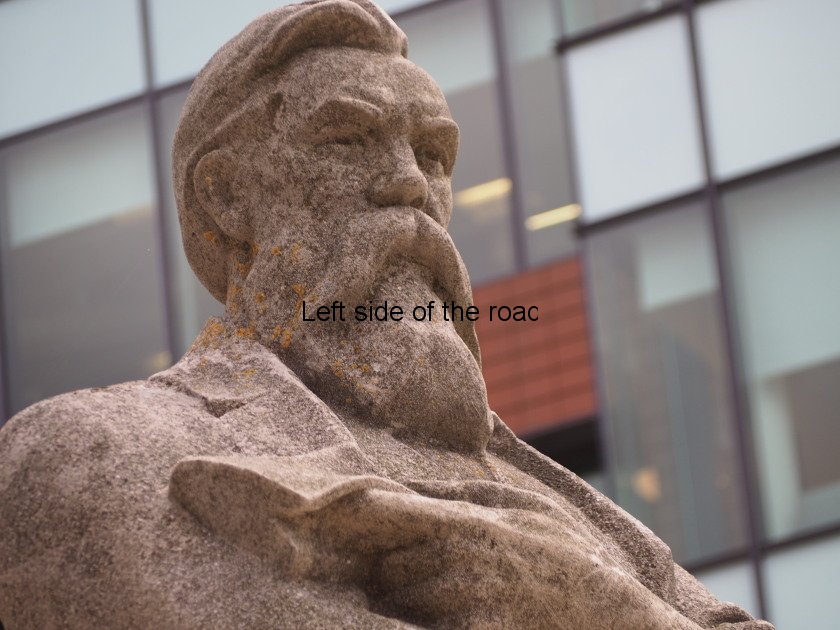

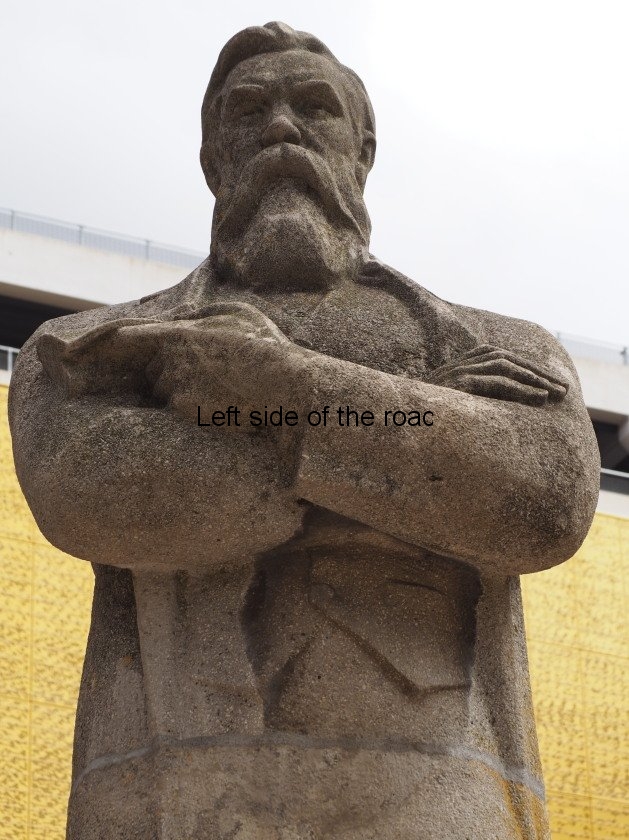

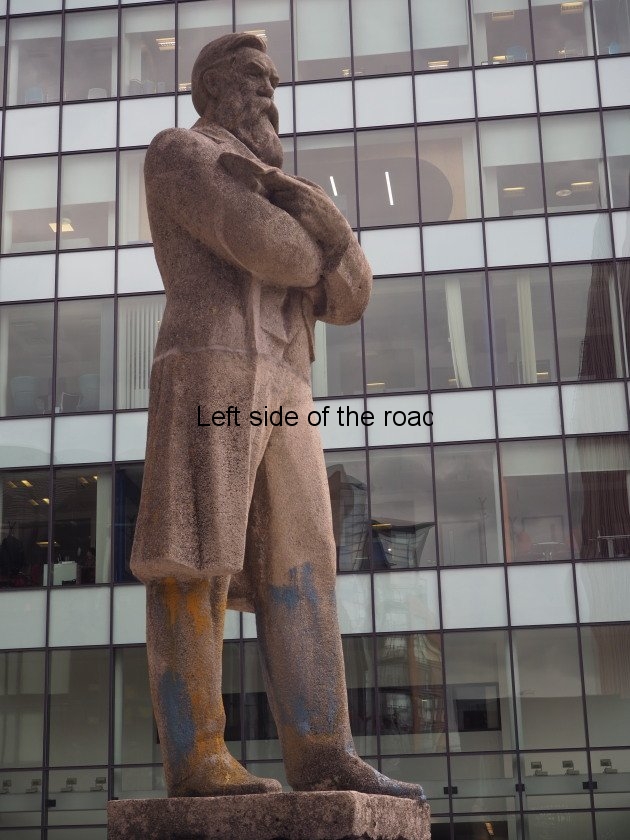

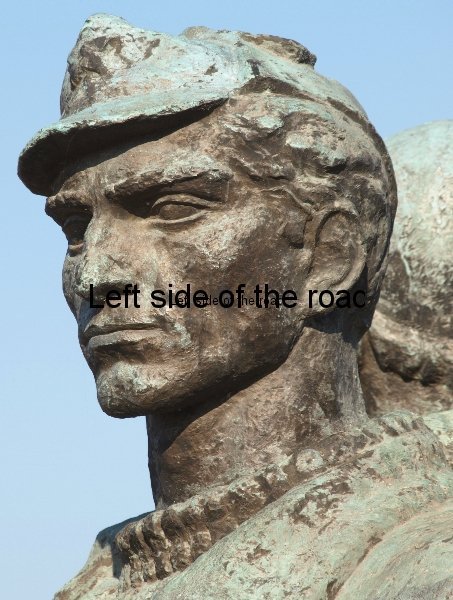

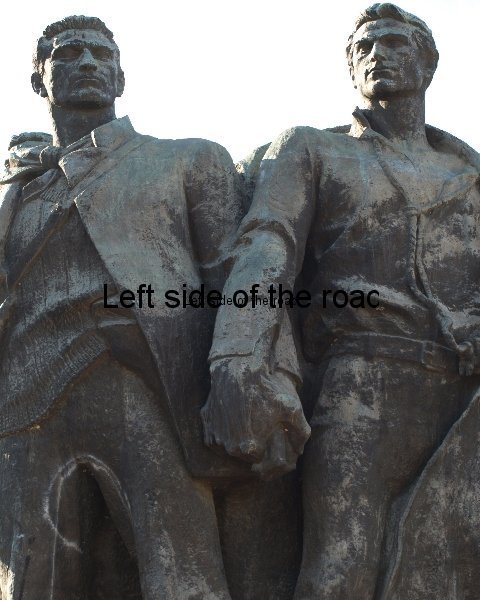

In its simple composition the statue epitomises the ideas of Socialist Realist sculpture. They form a tight circle so they are supporting, defending and depend upon each other and the direction in which they are looking gives the impression that they are covering the whole 360 degrees. It’s a defensive, rather than an attacking stance and in that way represents the way they dies – surrounded by an overwhelmingly superior force. But at the same time they wouldn’t have just been waiting for the enemy and the (imagined) depictions above try to give a more realistic representation of their ‘last stand’. What we have here is a symbolic representation of unity, solidarity and comradeship.

They are dressed in various clothing styles with one of them appearing to be dressed in a Partisan uniform but whether that would have been the case is unlikely due to the very nature of their mission – the elimination of a locally known tyrant and collaborator.

There’s a look of determination on all their faces together with a tranquillity as if they understand the circumstances and the inevitable acceptance of their lot, their fate. In the sort of war they were fighting any Partisan had to realise that once they had taken up arms they had to accept that all might not go well. This was total war and the Nazis would give no quarter – but then neither would the Partisans. Anyone who didn’t accept this should stay at home, let others do the fighting. Victory necessitated sacrifices – aim should be to make those as small as possible.

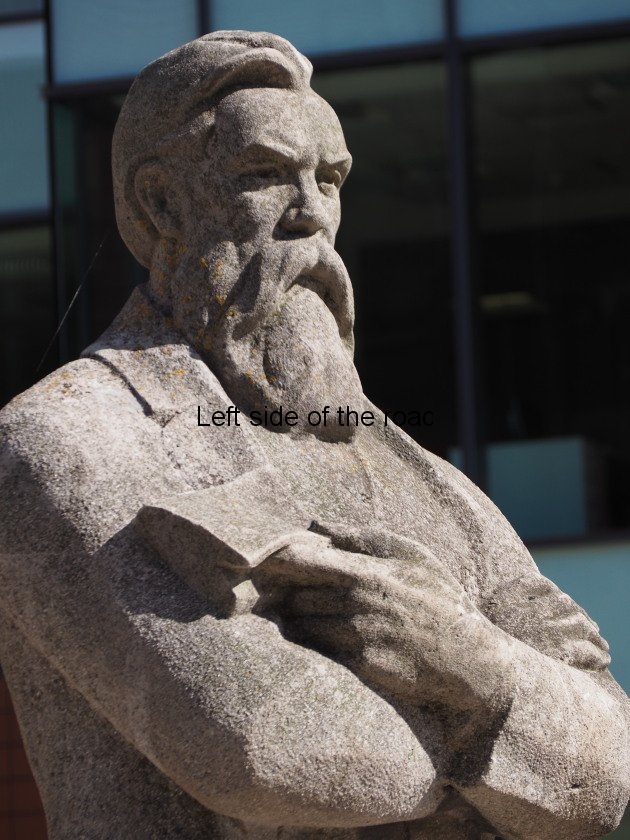

It’s very difficult with any degree of certainty to say exactly which of the five figures represents the real person and as they are in a circle there’s no real starting point so I’ll start with the figure that most clearly seems to be in uniform.

The uniform is typical of that seen on other lapidars throughout the country. He’s wearing a heavy jacket under which is a thick woollen jumper. He has a wide belt tied, not buckled, around his waist and into this is tucked a pistol. This pistol has a huge grip (similar to that carried by Bajram Curri in the statue to him in the town that bears his name). The pistol is attached to a twisted leather lanyard which goes around his neck, under the collar of the jacket. On his head he wears the typical Partisan cap, with the red star at the front. He is wearing sandals – with thick woollen socks – the strap and buckle on the left foot visible and cords crisscross the trousers of both legs, on the shins.

He is holding what looks like a Beretta Model 38 sub-machine gun with the forefinger of his right hand on trigger and his left hand supporting barrel in front of magazine, the bottom end of the magazine resting against his left knee.. Here is one of the examples of mindless vandalism which this monument has had to suffer and the end of barrel has been sawn off – this must have provided the thief with enough to buy a raki, not much else.

He stands with his legs slightly apart, standing steady, giving an impression of solidity, determination, of not going to move. He is looking slightly to his left.

5 Heroes of Vig – Solidarity

One interesting, human touch is that the left hand of the fifth in the group is placed protectively, supportively, on his right shoulder. This again emphasises the idea that these are Comrades united in a common cause – whatever might be the consequences.

5 Heroes of Vig – Haderi 1984

Carved into the rock against which he is standing, close to his feet be can see the name of the sculptor, Shaban Halil Hadëri, and the date 1984. As I have stated elsewhere, for example the Martyrs Cemetery in Lushnjë, it wasn’t until the mid-1980s that the name of the artist started to appear on Albanian lapidars, demonstrating a softening of the approach towards the idea of individuality in art. As I’ve stated above this particular statue (apart from moving around a lot more than most) existed in an earlier, plaster version which was created in 1969. Although it’s impossible for me to say given that that version was almost certainly destroyed when the new one was installed, I would very much doubt whether Hadëri’s name appeared on the original.

Hadëri also was responsible for the monument to 1920 in Qafe e Kociut (close to Vlora) and also worked with Mumtaz Dhrami and Kristaq Rama on the Vlora Independence Monument.

I must stress, again, that here I’m in no way denigrating the art, skill and imagination of the artist. But, in the end, he was only one of a number of skilled individuals who produced this fine example of Socialist Realism – where are the names of the others?

5 Heroes of Vig – Peasant Partisan

The next in the circle is not in uniform but is wearing the comfortable, winter clothing of a peasant. On his head he has a qeleshe (the felt skull-cap) on his head with a long headscarf wrapped around his forehead with the scarf trailing behind him. He wears a tight-fitting shirt and an open xhamadan (the traditional tight, short waistcoat) which has decorated trimming on the edges. He wears the traditional tight-fitting peasant trousers (tirc) which have the V shape at the front at the bottom, as they go either side the opinga (shoes) but these are without the sheepskin pompom. There are signs of decoration on the opinga. It looks as if there is a great coat hanging from his left shoulder, almost falling to the ground – the bottom edge of the coat can be seen hanging down behind his legs.

Around his waist is an ammunition belt with 4 pouches visible and 5 bullets in each. In holds a bolt-action rifle, his right arm fully extended and gripping the weapon at the trigger mechanism, his forefinger pushed through the trigger guard. His left arm is bent at right angles with his hand holding the gun at the point where the barrel departs from the rest of the mechanism – so the rifle is across his body from bottom right to left by his elbow. This weapon is not in a firing position but we know he is prepared to do so at any moment. Another small detail is the broken ring to which a strap would be attached which can be seen on the butt of the rifle. The end of barrel has also been stolen by the short-sighted, ignorant, rubbish rats.

His head is turned almost fully to the left and sports a moustache – almost always the differentiation that demonstrates a background of the country rather than the town (as is the sort of clothing depicted).

The third is basically in civilian dress, in the clothes of the urban working class. There’s a woollen jumper (with vertical stitching) under his jacket and he wears normal, contemporary trousers. On his feet are closed toe sandals – the straps and buckles of both feet visible. Around his neck is a large scarf, tied with large knot – this is not for warmth as this is the red scarf of a Communist. He is bare-headed.

A narrow, leather strap comes over his left shoulder, across his chest, to an unseen bag/pouch on his right hip. There’s an empty holster on a waist belt, seen under the left hand edge of open jacket, rucking up his jumper. In his right hand he holds an automatic pistol – possibly a luger taken from the enemy (this has also been vandalised and the end, just a few centimetres are missing). This gun, yet again, is not in a firing position but gives the impression that he ready to do so. There’s a sense of dynamism, movement, in his stillness. His arm is away from his body, the wrist bent in towards his leg and the gun pointing down it but could come up at any time – a coiled spring?

His stance the same as the others, feet slightly apart and steady and he is looking partially to his left.

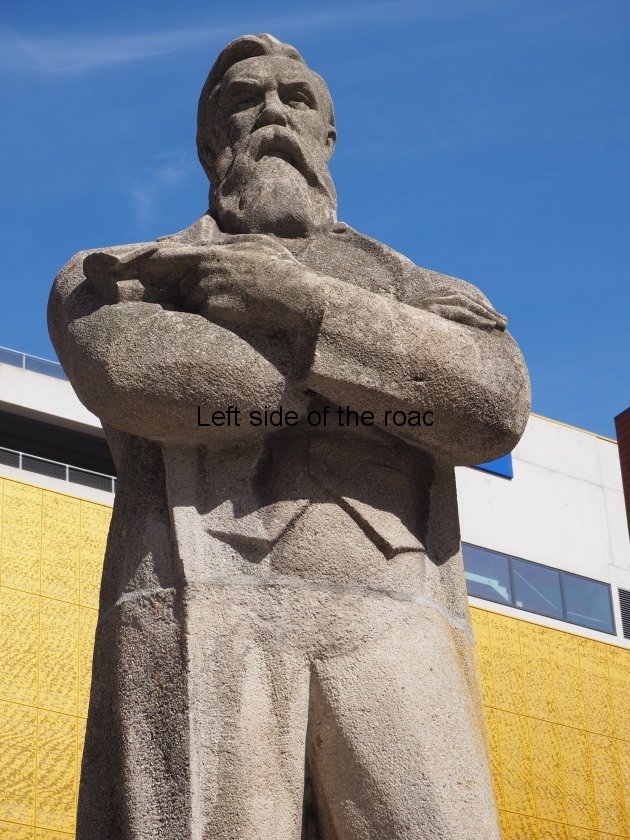

This statue is all about solidarity and comradeship and the connection between the third and fourth of the five heroes is something I’ve never seen before, not even in Albania where the lapidars celebrate unity in struggle and certainly never in any other country. Here we see the left hand of the Partisan being gripped by the right of his comrade.

5 Heroes of Vig – Solidarity, Comradeship and Unity

Their arms are touching from the elbow to the wrist and the hand of the fourth partisan is over that of his comrade hand, with his fingers in the palm and the thumb pressed against the fingers. This grip is returned in the same manner. There’s an impression that this has just happened, it has a vitality and feeling of immediacy. It seems to encompass the fate of the group as a whole. They know their fate, they are heavily outnumbered and the chances of survival are minimal – capture certainly would have led to an end in a Nazi torture chamber. They were not separated in life and wouldn’t be in death.

This is a slightly more intimate, but telling the same story, as the hand on the shoulder of the first Partisan described above.

It’s these little depictions of intimacy and the unexpected introduction of something that is so far from fighting and warfare that makes Albanian lapidars so unique in 20th century Socialist Realist sculpture and art in general. Another example of the unusual and unexpected is the small bunch of flowers in the left hand of the statue of Liri Gero, behind the National Art Gallery in Tirana.

The fourth hero is another who is more in civilian rather than military dress. He is wearing the clothes of the urban working class of the epoch. He has a tight-fitting shirt and his trousers have a turn ups which rest on top of sturdy boots. There’s a long, heavy overcoat but only his left arm is in the sleeve and the coat just hangs across his back. With his right hand grasping that of his comrade this stresses the closeness between them. He is also bare-headed and his stance is the same as the others, steady, rock solid, not going to give in. He looks to his right but not directly at his comrade as he is covering an area around them not necessarily covered by any of the others. An idea of continual vigilance, knowing what’s happening and what might happen next.

Around his neck, and under the collar of his shirt, is a lanyard and unites to become twisted just on his chest, beside a shirt button – many of the lapidars have these tiny details. This is attached to a ring on the butt of a pistol, in a holster, which is attached to his belt and rests on his left hip – most of the gun being obscured by the overcoat.

5 Heroes of Vig – pistol in holster

In his left hand he holds a Beretta Model 38 sub-machine gun, just behind the magazine. This is pointing up from right to left, with the barrel pointing into the air. This is not a firing position and he’s not ready, as some of the others are, to get into a firing position within seconds. He’s a fighter but in this image he is representing more the idea of comradeship and solidarity – which rests very much on the willingness and ability to use arms – rather than depicting the role of a Partisan. Although the end of the machine gun barrel is away from the main body of the sculpture this is still in place, not having suffered the attention of the petty thieves.

The stance of the fifth in the group is different from all the others. He stands side on so we only see the right hand side of his body. He has the look and wears the clothing of a peasant rather than someone from the city. He has short-cropped, curly hair (uncovered) and sports a moustache – often, though not always, an indication of a peasant background. Although his body is in profile he looks straight out at the viewer.

He seems to be dressed in similar clothing to the other peasant of the group already described, with a xhamadan over, this time a loose, short-sleeved shirt, the tirc but with sandals on his feet. Around his waist we can see a couple of ammunition pouches attached to his belt, a full one holding six cartridges and a partial one with two cartridges showing. In his right hand he holds a very long, bolt-action rifle which extends to just above his feet to the height of the shoulder of his comrade on the left. The machine gun of his comrade on his right is almost touching his knee.

5 Heroes of Vig – Weapons

As I’ve mentioned before his left hand is on the right shoulder of the comrade on his left thereby completing the circle and the show of unity.

Although this bronze version is relatively late in the history of Albanian lapidars it encompasses all those elements which had developed over the 40 years of socialist thinking about art. Even though it had its genesis in the 1969 version, where many of these elements were introduced, the present day statue, created 15 years later took those elements and made them much stronger, providing a vitality which was missing in the original and physically tightening the group so their unity is emphasised. In a sense the early version shows the group falling apart whereas the 1984 version shows us that nothing will ever break them apart – even death.

When the ‘Five Heroes of Vig’ had been exiled to beside the Shkodër Martyrs Cemetery – once a clean, quiet and pleasant location beside the river but now the site of the sprawling city rubbish dump – it had a feeling of dirt and neglect, and then it was vandalised. Before it was moved to its present location it obviously underwent a certain level of renovation and looks almost as good as it would have done in the centre of the town.

Apart from the damage done to the ends of the weapons there’s a small amount of written graffiti, more of the ‘I wus here’ kind but things are much better now than when I first saw the statue in 2011.

It’s location is not the best, it’s literally on the edge of town, on the last roundabout before the road leads to the border with Montenegro, but being placed on a circular, stone plinth it’s now in a place where more people can appreciate the story it tells.

Location:

From the roundabout next to the Rozafa Hotel (and the buses to Tirana) head north-east along Rruga Qemal Draçini which becomes the town’s market as stalls start to spill out on to the pavement. Continue north until arriving at Sheshi Ura e Maxharrit. This is coming to the end of the town proper and this is where you can find furgons to the towns to the north of Shkodër and the Montenegran border at Hani i Hotit as well as the early morning (07.30. more or less) departure to Thethi.

From the square continue along the SH1, passing the old, now very much overgrown, town cemetery and after about 10 minutes (walking) arrive at the roundabout with the lapidar in the centre.

GPS:

N 42.089302

E 19.507358

DMS:

42° 5′ 21.4872” N

19° 30′ 26.4888” E

More on Albania …..