TOS-1a firing

The war in the Ukraine – what you weren’t told – 2022

The war in the Ukraine – what you weren’t told – 2024

The war in the Ukraine – what you weren’t told – 2025

The war in the Ukraine – what you are not being told – 2026

The war in the Ukraine – what you weren’t told – 2023

01 January 2023

Drone strike; Russia enters Klesheevka; with analysis of Putin’s New Year Address: conclusion is the west is not trusted.

New Year Address to the Nation – Vladimir Putin

02 January 2023

New Year missile and drone strikes continue across Ukraine as NATO recognizes scale of conflict.

03 January 2023

Ukraine: when will it reach the end of its propaganda line?

03 January 2023

Russia strikes Druzhovka; admits 63 killed at Makeyevka [later revised up]; Polish mobilisation and entry into the Ukraine war and how that would impact on the future of NATO.

04 January 2023

Can NATO and the Pentagon find a diplomatic ‘off-ramp’ from the Ukraine War?

04 January 2023

Ukrainian soldiers considering a plan to withdraw from Bakhmut.

04 January 2023

Russia approaches remaining roads in Bakhmut; Ukraine offensive fails in Kremennaya; Makeyevka 89.

04 January 2023

Putin’s plan to stop Ukraine turning to the west has failed – our survey shows support for NATO is at an all-time high. [What these ‘academics’ don’t realise is that Ukraine hasn’t acted independently for years – since at least 2014. And considering so many are now out of the country – and unlikely to return – the fate of the country continues to be decided by others. This ‘analysis’ is simplistic in the extreme and totally ignores reality. As always, follow the money.]

05 January 2023

Ukraine and Russia: waiting for the next phase?

05 January 2023

Wagner assault units are storming SOLEDAR! [An annoying presentation style – but makes some interesting points nonetheless.]

05 January 2023

US admits Russia Bakhmut advance; Russia claims Solidar gains; US and France to provide light armour; what are the circumstances of a Russian offensive; the consolidation of Russian society.

05 January 2023

The Establishment Left and Corporate America – the Jimmy Dore show on the redundancy of the so-called ‘progressives’ in the US Democratic Party.

05 January 2023

Despite Russian setbacks, an end to the conflict is not yet in sight. [Yet another article from The Conversation which demonstrates that a not inconsiderable number of British ‘academics’ are shamelessly acting as paid propagandists for the the Ukraine/NATO narrative. As always, follow the money.]

06 January 2023

Western escalation in Ukraine: sending in armour – but is it too little too late?

06 January 2023

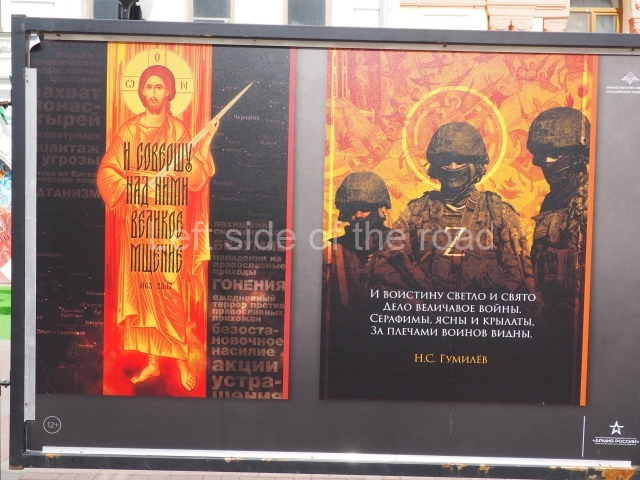

Zelensky’s bloody war against the Ukrainian Orthodox Church.

06 January 2023

Russia breaks through in Soledar; Putin Announces Ceasefire, US Germany Send Armour To Ukraine.

06 January 2023

The Grayzone live on; Nicaragua; Nazis in the Ukraine; situation in the Donbass; the implications of the election of the US Speaker McCarthy and the possible implications on the war in the Ukraine; Twitter’s Russiagate files exposed. [A long discussion which covers many issues.]

06 January 2023

Why Russian soldiers’ mothers aren’t demonstrating the strong opposition they have in previous conflicts. [Whatever the aim of this article the most important idea here, as far as we are concerned, is that IF there were such huge Russian casualties, as are claimed by both the Ukrainians and their NATO backers, then the existing structure in Russian would have broken through this supposed move of opposition on to social media. Contrast that with the structure that doesn’t exist in the Ukraine. So many family members are no longer in the country that they don’t even know what might have been the fate of their sons, fathers, etc., let alone make a public statement to that fact.]

07 January 2023

Has NATO support been beneficial to the Ukraine – or not? Douglas Macgregor.

07 January 2023

Russia on brink of capturing Soledar; Ukrainian Bakhmut defences crumble; West rushes weapons to the Ukraine – whether they are of use is not taken into consideration.

07 January 2023

Military summary and analysis.

08 January 2023

Latest US arms shipment to Ukraine cannot solve Kiev’s fundamental problem.

What’s ahead in the war in Ukraine. [The last article referenced in the podcast above.]

08 January 2023

Ukraine admits heavy losses as Russia takes Podgorodnoye, most of Soledar and encircling what’s left.

08 January 2023

Biden’s existential angst in Ukraine.

09 January 2023

BBC and it’s claim of ‘impartiality’

Contrast both the headlines and the content of two articles that address to similar events that took place in the Ukraine in the space of 8 or 9 days. Although the facts (at the time of writing this) about the Russian attack on barracks in Kramatorsk are still to be confirmed before any more information becomes available the BBC is already banging the Ukrainian propaganda drum. Now that should come as no surprise, this has been the case for the last ten months and a bit.

Neither should it be a surprise that the BBC follows the dictat of the UK government when it comes to the news about a war in which, officially, Britain is not involved. Keeping people stupid is the name of the game. The problem arises when the BBC argues that it is being impartial in its news reportage – as claims the rest of the British mainstream ‘media’. Through this maintenance of the line that whatever everything Ukraine says is true (and thus that they are ‘winning’ the war – against all rational analysis) this allows western governments to continue to expend huge resources in support of the Nazis in the Ukraine in a desperate attempt to do serious damage to Russia. But, ultimately, those who will really suffer from this propaganda campaign are the Ukrainians themselves. As the corrupt Oliver North said recently the fight against Russia will be carried out by American bullets and Ukrainian blood.

Ukraine claims hundreds of Russians killed by missile attack (3rd January 2023)

Ukraine denies Russian claim it killed 600 soldiers (9th January 2023)

09 January 2023

Biden has never had a grasp of international politics. Was an arrogant fool in 1997 and remains so to this day – with added age degeneration.

09 January 2023

Russia claims Ukraine collapse and retreat from Soledar; Russian arms production; protests in Brazil.

09 January 2023

Military summary and analysis.

28 December 2022 (but only encountered 10 January 2023)

Russia winning the electronic war in Ukraine.

10 January 2023

Russia presses Ukraine in Soledar and Bakhmut; Ukraine mulls retreat; Patrushev says Russia fights West – not Ukraine.

10 January 2023

Washington has trouble refilling the Strategic Petroleum Reserve after 220 million barrel draw.

10 January 2023

Colonel Douglas Macgregor on Bakhmut battle – and huge Ukrainian casualties; danger of NATO confronting Russia directly. Ideas on a possible Russian offensive. No one in the ‘west’ is prepared to admit they have lost.

11 January 2023

What (more reasonable) Western analysts say comes next for Ukraine.

11 January 2023

Life on Russia’s home front after ten months of conflict.

11 January 2023

Russia claims Soledar captured and remaining Ukrainian troops surrounded; West debates sending tanks to Ukraine.

11 January 2023

Military summary and analysis.

11 January 2023

Poland verges on total collapse, the government caught hiding the truth from Polish people.

12 January 2023

The Russian sledgehammer is beginning to fall in Ukraine. Another Macgregor interview. [The of the best of Macgegor’s analyses of the Ukrainian situation – taking into account the present situation with historical comparisons.]

12 January 2023

Large number of Ukrainian soldiers suffering from tuberculosis.

12 January 2023

Can a nuclear war be avoided? — Scott Ritter. Emphasising the reality that Russia doesn’t have any trust in the ‘West’.

12 January 2023

Russia consolidates control of Soledar and focuses on Bakhmut; Russia reshuffles military command structure; Kiev floats and rejects armistice.

12 January 2023

180 million barrels of crude may never be returned to the [US] Strategic Petroleum Reserve.

12 January 2023

Military summary and analysis.

12 January 2023

The bloody battle for Soledar and what it tells us about the future of the conflict. [Yet another ‘analysis’ by this so-called ‘academic’. As always with The Conversation (when it comes to the Ukraine, on other matters it’s quite good) ‘follow the money’.]

12 January 2023

Can the United States provide an ‘off-ramp’ for Putin?

12 January 2023

The Ukrainian Demilitarized Zone – ‘negotiations’ start at a dead end.

13 January 2023

Will western main battle tanks turn the tide in Ukraine? What do Russian gains in Soledar mean?

13 January 2023

Russia claims Soledar victory; Ukraine troops trapped in Bakhumt; Ukrainian Soledar counter-attacks fail.

13 January 2023

Russia claims Soledar victory and trapping of Ukraine troops in Bakhumt; Ukraine Soledar counter-attacks fail.

14 January 2023

Russia missile strike; advances in Bakhmut; German public criticism of tank transfers; US Navy weapons stocks depleted.

15 January 2023

Kiev says Ukraine cannot shoot down ballistic or supersonic missiles; Washington Post says Kiev may retreat from Bakhmut.

15 January 2023

Military summary and analysis.

16 January 2023

German general tells US generals to lose the Ukraine War as soon as possible to prevent losing the Empire in Europe.

The two links below are not ‘directly’ connected to the war in the Ukraine but it does put the approach of the UK government to the conflict in context.

16 January 2023 (published 10 January 2023)

The UK’s 83 military interventions around the world since 1945.

16 January 2023 (published 12 January 2023)

Britain’s 42 coups since 1945.

16 January 2023

As West sends more armour to Ukraine why ‘turning the tide’ is still fantasy.

Some statistics from around minute 20;

Russia has; available on the battlefield 2,800 tanks and 13,000 armoured vehicles;

in storage 10,00o tanks and 8,500 armoured vehicles.

16 January 2023

Russia prepares Bakhmut ‘cauldron’; German ex-General calls for peace and says West risks defeat and/or World war Three; an analysis of the failure of western sanctions against Russia and the fundamental reasons why by French anthropologist Emmanuel Todd.

16 January 2023

Military summary and analysis.

17 January 2023

What if Russia won the Ukraine War but the western press didn’t notice?

17 January 2023

Ukrainian Bakhmut crisis deepens; Zelensky fires key adviser; Bloomberg confirms Russian oil surge; ‘life is normal in St Petersburg’ and the failure of economic sanctions; the ‘blow-back’ on the USA of their irrational desire to destory the Russian Federation.

17 January 2023

NATO wonder weapons. [A discussion about the practicalities of the ‘game changer’ weapons that the west is proposing to send to the Ukraine. I can’t find anything which doesn’t hold together. The first hour deals with that issue, the second a Q+A which also includes some interesting points.]

18 January 2023

Supply of advanced tanks will give Kyiv an edge over Russia and move it closer to NATO. [Yet another contribution form a NATO/US/UK/EU paid ‘academic’ flunky. Again follow the money And who is the Kyiv Transatlantic Dialogue Center?]

[This is a strange site, referenced in the above article, which seeks to ‘prove’ Ukrainian claims on the number of Russian armour either destroyed or captured. But it’s merely a site with links to pictures that could have ben taken anywhere and at any time in the past. This ‘academic’, nonetheless considers this ‘credible’ evidence of what the west is promoting.]

Attack on Europe: documenting Russian equipment losses during the 2022 Russian invasion of Ukraine.

19 January 2023

Russia captures Kleshcheyevka; Bakhmut ‘cauldron’ looms; Zaluzhny warns about dangers to Siversk; Biden and Scholz quarrel about supplying tanks to Ukraine.

19 January 2023

Spoils of the Sanctions War – NATO lion meets Russian tit for tat.

19 January 2023

Jeffrey Sachs: The war in Ukraine and the missing context and perspective.

20 January 2023

US and allies send more weapons to Ukraine in the absence of real solution.

20 January 2023

Bakhmut operationally encircled; Russian advance in Zaporozhye; West talks tank deliveries in Ramstein; retired German General Kujat criticises NATO’s action in the Ukraine.

20 January 2023

Will Russia opt to continue the war into 2024?

21 January 2023

Russia offensive make rapid gains in Zaporozhye; Ukraine operational crisis in Bakhmut; Germany says ‘No’ to sending tanks to the Ukraine.

22 January 2023

Viewing Ukraine through the Davos lens.

22 January 2023 (Originally published by The Guardian newspaper in 2017.)

So, perhaps, surprising that The Guardian is now beating the ‘support democratic Ukraine’ drum.]

Ukraine’s far-right children’s camp: ‘I want to bring up a warrior’.

22 January 2023

Russia advances further in Bakhmut, Siversk and Zaporozhye; US tells Ukraine it is losing attrition war and should leave Bakhmut.

22 January 2023

War to the last Ukrainian. Violent handout of draft notices in Ukraine, January 2023 (Videos).

22 January 2023

Military summary and analysis.

23 January 2023

Russia fighting west of Bakhmut and closing the trap; Russia pushes towards Zaporozhye City, threatening a new military crisis for Ukraine. [Also three interesting articles from Americans questioning the war. Links in video information.]

23 January 2023

Russian gains; US gears up for Crimea escalation; US proxies strike China/Pakistan in train bombing.

24 January 2023

German Greens on the warpath.

24 January 2023

German General Kujat warns the Ukraine War is lost, revives the stab-in-the-back charge against the US and NATO for ‘exposing Germany to Russia’.

24 January 2023

Russia begins new Vuhledar offensive; Russia advances in Bakhmut and Zaporozhye; big purge of politicians strikes Kiev; the debate about supplying western ‘modern’ tanks – from about 42 minutes to end.

25 January 2023

Russia closing Bakhmut cauldron; Belarus rejects Ukraine offer of a ‘non-aggression pact’; West escalates and sends Kiev tanks; interesting articles references around 45 minutes; Russian casualties discussed around 63 minutes.

25 January 2023

West risks war with Russia over escalating military aid – Geoffrey Roberts

25 January 2023

US to send M1 Abrams tanks to Ukraine; US-backed terror targets Myanmar’s upcoming elections.

25 January 2023

Douglas Macgregor – What are the damages for the Russian side? [Includes an analysis of casualties on both sides.]

26 January 2023

Russia aims to surround Vuhledar; most recent missile strike against Ukraine; more on western tanks – and the problems associated with their provision, west mulls giving Kiev fighter jets and even more missiles.

26 January 2023

John Helmer: Blinken concedes war is lost – offers Kremlin Ukrainian Demilitarization; Crimea, Donbass, Zaporozhe; and restriction of new tanks to Western Ukraine if there is no Russian offensive.

26 January 2023

Zelensky admits: ‘Ukraine war is good for business’!

26 January 2023

Ukraine’s Zelensky sends love letter to US corporations, promising ‘big business’ for Wall Street.

26 January 2023

Douglas Macgregor – A huge offensive. [What the Russians might do and the failings of the Ukrainians. Although Macgregor is informative on the military aspects of the war but his right-wing political views always come through.]

27 January 2023

USAID quietly unveils plans to export Ukraine’s digital governance model around world.

27 January 2023

Russia close to capture Vuhledar; launches big missile attack; Blinken and Nuland floats ‘peace offer’.

28 January 2023

How tanks from Germany, US and UK could change the Ukraine war. [Yet another ‘game changer’.]

‘Western officials had hoped that Ukraine may be able to mount an offensive as soon as this spring. They believe there is now a window of opportunity while Russia struggles to recruit and rebuild its battered forces, and to replenish its dwindling supplies of ammunition.’ ]Assertions which are never accompanied with proof.]

28 January 2023

Russia presses forward in Bakhmut, Vuhledar and Orekhov; the western weapon ‘game changers’; Rand warns US overinvested in Ukraine and the prolongation of the war is not in the interest of the USA;

28 January 2023

The Russian Battalion Tactical Group, the New Atlas with Alex of Donbass Devushka. [A valuable introduction to Russia’s military organisation – useful for those not versed in the world’s militaries.]

A very much throw away comment, but important in the context of the NATO tanks that are supposed to be supplied to the Ukraine some time in the indeterminate future, that all Russian conscripts are trained of how to work with armoured ordinance in order to not be crushed by their own side. There is no way that Ukrainian conscripts will have any understanding of this idea. That point is made around minute 16.

But perhaps the most important thing to take from this discussion is that the Russian army has a strategy (it might not always work) whereas the Ukrainians don’t. Taking their decisions on the initiative of the British this is not surprising. The last ‘war’ the Buffoon had to fight was the pandemic. There was never any hint of a strategy then – and even now such a strategy doesn’t exist.

29 January 2023

‘Mainstream media’ admits Russia about to capture Bakhmut; Ukraine Vuhledar counter-attack fails; US equipment crisis – logistical and training problems of sending western material to Ukraine and the consequent depletion of all NATO nation’s military resources.

30 January 2023

Western volunteer in Bakhmut admits Ukraine is losing; is the western tank card a bluff?

Avoiding a Long War – US policy and the trajectory of the Russia-Ukraine conflict, RAND, January 2023. Document referred to above.

30 January 2023

Putin just pulled off the ultimate sneak attack against the West. [Not too sure about the advert for the ‘sponsor’ at around 10 minutes to the end.]

30 January 2023

Imperial dominance disguised as democratic deterrence.

30 January 2023

Wall Street Journal admits Bakhmut almost cut off; Russia pushes forward in Vuhledar; militaries in western Europe (especially Germany and Britain) concerned about armour and other war materiel being sent to Ukraine; US military wants end Ukraine War – as it feels itself weakened against their main enemy – China. [Sound not particularly good for first 17 minutes.]

30 January 2023

Why, despite RAND’s recommendation, the Ukraine War is unlikely to end in a negotiated settlement.

31 January 2023

That didn’t take long: Latin American governments refuse to send weapons, Russian or otherwise, to Ukraine.

31 January 2023

Russia’s ‘sanction-proof’ trade corridor to India frustrates the Neocons.

31 January 2023

Russia’s Bakhmut ring tightens; UK mainstream media admits Russia close to Chasov Yar; Russia advances on Vuhledar.

31 January 2023

Preventing a long war, The Duran with Scott Ritter. [A very long discussion.]

31 January 2023

Ukraine: banned landmines harm civilians – Ukraine should investigate forces’ apparent use; Russian use continues. [Article gives the impression it’s holding Ukraine to account for its ise fo anti-personnel mines but then, slavishly, accepts Ukraine’s assertion that it’s a problem of rogue elements as they are going to ‘investigate’ the matter – as if they don’t know what’s going on on the front line. The article also ignores the documented incidents of the Ukrainian use of the very same mines in Donetsk City – which was documented more than six months ago, at least. Yet another NGO which claims independence but which is just another arm of the western propaganda machine.

Ukraine turns Donetsk into a minefield using banned ‘Petal’ mines – a video by a journalist, Eva Bartlett, who has been based in Donetsk City since the beginning of the Special Military Operation.

01 February 2023

The Pentagon’s plans for a perpetual three-front ‘long war’ against China and Russia.

01 February 2023

US threatens missiles, jets – but without taking into account the logistic difficulties; is the US merely trying to bluff Russia and hope that Putin will back down first; also US now starts to threaten Crimea; US seeks war with China by 2025.

01 February 2023

Mainstream media admits Bakhmut Encirclement is close; speculations on the recent (and continuing) purge of the Ukrainian ‘leadership’; Lavrov ridicules Blinken offer; the supply of western armour looks more precarious by the day; West pulls back on jets.

01 February 2023

Douglas Macgregor on the imminent destruction of the Ukraine and the effect this will have on NATO – a resume of the situation in the war at the beginning of February 2023. Interesting quote from podcast ‘The Polish army could invade Germany tomorrow morning and conquer it in a week’.

01 February 2023

Ukraine war: casualty counts from either side can be potent weapons and shouldn’t always be believed.

02 February 2023

EU snubs Zelensky on Ukraine’s membership; Setback ahead of Kyiv summit on Friday 03 February.

02 February 2023

Is NATO tired of Ukraine’s demands?

02 February 2023

Mozart pro-Ukrainian mercenary group meltdown over viral Grayzone video exposé. [Mozart’s founder admits to Ukrainian corruption and extra-judicial murders of Russian POWs.]

02 February 2023

Ukraine war: how US-built F-16 ‘Fighting Falcon’ could help Kyiv move on to the offensive. [Yet another jingoistic article – which just brushes off the issues of training and logistics, as if anyone could just jump into the cockpit and become an expert within weeks.]

03 February 2023

Russia new Kremennaya offensive; only one road in and out of Bakhmut; Pentagon tells Congress that Ukraine is unable to take Crimea; ‘press gang’ on Ukrainian streets; the village of Sacco and Vanzetti; who destroyed Nordstream?

03 February 2023

Douglas Macgregor talks about the training and logistical issues related to the introduction of western weapons to Ukraine. [An audio interview with an extremely annoying and meaningless video with dogs. But … very significant and important statement between 09.13 and 10.38 minutes. And calculates 150,000 Ukrainian dead at 12.18 minutes. Ukraine has lost.]

03 February 2023

As US proxy war rages against Russia, US seeks war with China by 2025. [Another long, yet still interesting discussion.]

03 February 2023

Grayzone live with Max Blumenthal and Aaron Mate – the Chinese ‘spy’ balloon and the US multi-million project on spy balloons; the end of the western Mozart mercenary group; the bogus story of ‘Russiagate’; British politicians starting to speak about sending NATO (and presumably British) troops to the Ukraine. A long discussion which covers many points but worth the effort.

04 February 2023

Jimmy Dore drops fiery anti-war monologue (this time on provoking China) on the Tucker Carlson show.

04 February 2023

As Russia encircles Bakhmut Zelensky decrees ‘No Surrender’; New York Times writes Ukraine using its conscripts as cannon fodder; discussion on Russian casualties; more on the attack on Nordstream; US mulls China conflict; rumours to end war.

05 February 2023

US fails miserably in efforts to isolate Russia.

05 February 2023

UK Ministry of Defence admits Bakhmut is isolated; EU struggles to find tanks; Russia massively increases arms production; potential Russian Spring offensive; Ukraine follows French and German lead by promising negotiations in bad faith; the errant balloon over the US.

05 February 2023

Energy saving light bulbs and Ukraine’s membership of the EU; US Department of Justice to transfer assets seized from sanctioned Russians to be sent to the Ukraine; western skilled engineers to be embedded with Ukrainian units to assist in the maintenance of western provided munitions – starting with hundreds, could it get up to thousands?; why doesn’t Zelensky not donate some of his private wealth for the Ukrainian war effort?; Mission creep as in Vietnam in the 1960s; long range weapons aimed at Crimea; China spy balloon

06 February 2023

Latest US arms package (and a list of weaponry that has still to be produced) and US provocations versus Russia and China. [Includes an interesting (short) discussion of the meaning of 14 and 88 – the Germans are sending 14 Leopard 2 and 88 Leopard 1 tanks at minute 26.00.]

06 February 2023

The economics of the Ukraine proxy war with Michael Hudson and Radhika Desai.

06 February 2023

For Ukraine continued resistance is futile. They should sue for peace now. George Galloway and Scott Ritter. [A few Ritter quotes; ‘Your mouths are writing cheques your body can’t cash’. ‘NATO can’t get out of the barracks’. ‘The British Army will run out of ammunition in one day’. ‘Everything the US government says is lies.’]

06 February 2023

Bakhmut on the brink of capture by Russia; big Russian gains in Kharkov; Zelensky loses key ally Reznikov and continuing changes in Ukrainian government; more on the German Leopard tanks; the affair of the wandering Chinese balloon.

06 February 2023

The Maidan sniper killings were pivotal for the 2014 Kiev coup – why is research into the massacre being censored in the West?

07 February 2023

Moscow provides update on Ukrainian losses.

07 February 2023

The new atlas – Chinese-Russian history with Mark Sleboda and Carl Zha – a comprehensive explanation of the last 800 years.

08 February 2023

Seymour Hersh: Navy divers + spooks + Norway took out Nord Stream 2 on Biden’s orders, using timer.

08 February 2023

Bakhmut about to fall; Russia says Ukraine leaving Kupiansk; will Britain be out on a limb when it comes to support of Ukraine when the rest of the ‘west’ pulls back?; report implicates Biden in Nord Stream attack in 2022.

08 February 2023

Russia-Ukraine War: Ex-Israel PM Naftali Bennett’s shocking revelations about US/UK/NATO/EU interference to prevent bringing the war to an end in March 2022.

09 February 2023

Elite splits over Ukraine shed a tiny bit of light on factions.

09 February 2023

Propaganda in the Ukrainian proxy-war, with Noam Chomsky, Alexander Mercouris and Glenn Diesen. The ‘unprovoked’ invasion of the Russians.

10 February 2023

How did the German Greens become the party of warmongers?

10 February 2023

Missiles, earthquakes and pipelines – US hegemony fighting on all fronts. Again on the difficulties of introducing western weapons in Ukraine and all it will do is extend the war. US refusal to lift sanctions against Syria following the recent earthquake and states it wants to destroy the country. Report that US destroyed the Nord Stream pipelines last year. Taiwan and the Solomon Islands.

10 February 2023

Big missile strike; Bakhmut siege tightens; Russia advances on Kupiansk; UK to send Typhoon jets, not F16s; Scholz and Baerbock ‘not speaking’.

10 February 2023

GrayZone – Rant against the war machine rally on 19th February 2023 in Washington, with Jimmy Dore; some of the US ‘left’ not being anti-war; the attack on the Nord Stream pipelines; the earthquake and the block on aid to Syria because of US sanctions; the Syrian ‘White Helmets’ the tool of US and western imperialism.

10 February 2023

The Duran – Nord Stream pipeline and sabotaging peace with Jeffrey Sachs.

10 February 2023

The Leopard’s Tale: U.S. weapons makers on a marketing spree.

10 February 2023

The West thought oil sanctions would cripple Russia, here’s why the plan backfired.

11 February 2023

Russia tests new systems most recent missile barrage; Bakhmut trap tightens; New York Times writes Russia may plan encirclement; threats against venues hosting meetings against the war.

12 February 2023

Russian soldier death rate highest since first week of war – Ukraine. [In this the headline says more than the body of the article. The Ukrainian figures are unsubstantiated – they never are – and the BBC always provides it’s (and that of the UK Ministry of Defence) get out by writing ‘The figures cannot be verified – but the UK says the trends are “likely accurate”.’ The word ‘likely’ appears in many BBC reports when it wishes to publicise matters that are, in all probability not likely.]

12 February 2023

West admits jets for Ukraine will take years and US sanctions blocking Syrian earthquake relief.

12 February 2923

Bakhmut siege tightens; Russia captures Krasnaya Gora; London Daily Telegraph economics editor cast doubts on the effects of western’ sanctions against Russia; Russian oil caps ‘watered down’; NATO back-pedal fighter jets; Zelensky plays western leaders ‘like a violin’; the decision to destroy the Nord Stream pipeline made by a ‘secret cabal’.

12 February 2023

‘Rules based international order’ to be imposed on Hungary – whether they want it or not.

12 February 2023

Zelensky shares photo of Ukrainian soldier with Nazi insignia, again.

13 February 2023

Russians slowly takes ground around Bakhmut.

13 February 2023

Is civilization at stake in Ukraine?

13 February 2023

Toll of Ukraine conflict on NATO assessed – Reuters.

13 February 2023

More balloons or UFOs? Is it all a distraction? Interview with Seymour Hersh and his article about the US involvement in the sabotage of the Nord Stream pipelines starts at 33.40 minutes to near the end. And with a very instructive and informative short video of Condoleezza Rice speaking about 20 years ago at 36.35.

14 February 2023 (originally broadcast 03 February 2023)

What becomes of NATO after the loss in Ukraine?

14 February 2023

Ukraine retreating from Bakhmut; Russia reaches Kupyansk and Liman; NATO out of stock of munitions; Stoltenberg makes strange speech which shows panic and lack of real understanding of logistics; confused and contradictory advice coming from the Pentagon.

15 February 2023

West’s ability to arm Ukraine continues to wane; western weapon systems won’t arrive for so-called Ukrainian ‘Spring’ offensive – and no time to train Ukrainians to use them; mainstream media starts to accept problems developing; US denies reality and continues to repeat their fantastical claims of Russian failures.

15 February 2023

Blood, money and imperial war.

No Nazis in Ukraine – says US/UK/NATO/EU, but the facts say otherwise.

15 February 2023

US official deletes tweet honouring Nazi collaborator.

15 February 2023

Ukrainian ‘commander’ shown with ISIS patch.

15 February 2023

Zelensky decorates military unit with ‘Nazi’ title.

15 February 2023

Russia closes in on Kupiansk and Liman; UK mainstream media admits NATO can’t – and never will – match Russia in production of ammunition; US depletes its ’emergency’ oil reserve.

16 February 2023

Russia in Paraskovievka and Bakhmut; more concern in the west that their ammunition stocks are being depleted; fewer NATO tanks than promised – especially Leopard 2 tanks from Germany; developments following Seymour Hersh’s article on the sabotage of the Nord Stream pipelines; both Stoltenberg and Sullivan have questions to answer.

16 February 2023

Douglas Macgregor – The Russian onslaught. In the first few minutes three interesting video clips about the current situation and the amount of ammunition available for the Ukraine by Austin, Stoltenberg and Milley. Scoffs at the saga of the ‘surveillance balloons’. Seymour Hersh’s article on the Nord Stream sabotage ”more than credible’. [On the Ukraine I find it difficult to disagree with much of what Macgregor says about the military aspect of the war in the Ukraine. But, at foundation, he’s just a right-wing shit. He considers those in control of the industrial/military complex as ‘left-wing’ and constantly makes references, in a negative manner, to those crossing the southern border with Mexico.]

17 February 2023

China-Iran ties on the right side of history.

18 February 2023

How America took out the Nord Stream pipeline.

18 February 2023

Russian Bakhmut pincer closing; Paraskovievka captured and Russian forces approaching Kupiansk; Macron says there should be no regime change in Russia. [Although Mercouris offers a reasonable analysis he can sometimes waffle, especially when it comes to military matters. That’s the case here but his comments on the Munich Security Conference are worth a listen and start at around minute 30.]

18 February 2023

‘United States is corrupted!’ – The Russian-Ukrainian war explained. Commentary by Jimmy Dore. [With an interesting short video of US representative being caught out in justifying NATO expansion as not being a cause for the war.]

19 February 2023

Russia pushes west of Bakhmut; gloom over the Munich Security Conference – an ‘acceptance of the partition of the Ukraine; ‘the end of the world as we know it’; disappointment after the expectation that Russia would ‘implode’ following sanctions; bizarre (and hysterical) reaction of world leaders to China’s Wang Yi announcement that China will be publishing a ‘position paper’ later in the week; Sunak’s ‘double down’ an acceptance of Ukrainian defeat?

20 February 2023

Europe’s second largest industrial base [Italy] sinks under the weight of energy costs as divisions open up in the ruling coalition.

20 February 2023

Russia’s Special Military Operation one year on: How the US started this war and where it’s heading. [Includes a couple interesting video clips; Wesley Clark, retired US general, 17.43 minutes; Victoria Nuland and the US support for Ukraine, 36.33 minutes; as well as a couple of ‘forgotten’ articles/reports; EU report that Georgia started the war against Russia in 2008, 34 minutes; and a very different approach by the Guardian to the politics of the Ukraine in 2004, 29.15 minutes.

20 February 2023

Biden empty handed in Kiev – merely more propaganda and hot air; Russia advances in Bakhmut; Borrell begs for ammunition; leaders from the ‘global south’ shun the ‘west’ in Munich – Financial Times article about this analysed at 45 minutes; has Russian gained supremacy of the skies about Ukraine?

20 February 2023

Military summary and analysis.

21 February 2023

Putin’s February 21 speech: hot takes – Putin speaks for a strong, self-sufficient Russia.

21 February 2023

EU gas price cap: an exercise in futility.

21 February 2023

Russia 15km from Kupiansk; Lt. Col Daniel Davis, in the magazine 45, compares the respective strategy and tactics of the two opposing forces, from minute 4.25; Biden’s Kiev trip draws criticism from US politicians (17.10 minutes); fractious meeting between Wang Yi and Blinken at the Munich Security Conference; 34.45 minutes, editorial in Chinese Global Times; 39.45 Putin’s State of the Nation address.

21 February 2023

Ukraine forcing ethnic Hungarians to fight Russia, Hungary outraged.

21 February 2023

Vladimir Putin delivered his Address to the Federal Assembly. [The full text.]

Ukraine war: President Putin speech fact-checked. [Read the speech above and then consider if the BBC’s ‘fact checking’ holds water.

21 February 2023

‘I am ashamed to be a European’ Irish MEPs slam EU for silence on Nord Stream blasts.

22 February 2023

Who’s winning and losing the economic war over Ukraine?

22 February 2023

Russia Centre Bakhmut, Russian Ministry of Defence disputes Prigozhin claims about being starved of ammunition; M of D statement at minute 2.30 and Prigozhin’s response; a strange and worrying internal conflict which only benefits the Ukraine; 46.15, ‘Battle of the Speeches’; Biden insults Putin in Warsaw; Putin’s speech more measured and with no personal attacks, also says sanctions have failed.

22 February 2023

Where is Russia’s winter offensive? Why should Russia carry out a big offensive if what they have already been doing is achieving their aim, i.e., the demilitarization of the Ukraine. President Biden substantially empty-handed in Kiev – form over substance.

23 February 2023

Russia taking Berkhova and tightens grip on Bakhmut; Wang Yi meets Putin and Lavrov, 35.00 minute; China slams US foreign policy in position papers: ‘US hegemony and its perils’, (46.40) and ‘Global security initiative concept paper’, (51.04).

US hegemony and its perils. [Full text.]

23 February 2023

Center for Strategic and International Studies (CSIS) war game: US vs China over Taiwan – provoking war to preserve US primacy.

23 February 2023

Jeffrey Sachs at the United Nations Security Council meeting on the Nord Stream pipelines sabotage.

23 February 2023

Foreign Ministry Spokesperson Wang Wenbin’s Regular Press Conference on February 23, 2023. [In answer to a question from CCTV (Chinese Central Television) towards the end of the press conference he states ‘The US is the No.1 warmonger in the world’ and makes direct reference to the US’s maintenance of world ‘hegemony’.]

24 February 2023

Scott Ritter – the Russian onslaught coming.

24 February 2023

China’s position on the political settlement of the Ukraine crisis.

24 February 2023

Discussion between Gonzalo Lira and Yves Smith. [A long discussion, almost two hours, but covers many aspects of the current conflict in the Ukraine – as well as some thoughts on the covid pandemic.]

24 February 2023

Russian forces captures Bekhova; China’s Ukraine ‘Position Paper’ criticises ‘West’; UN resolution demonstrates ‘west’ out of ideas to isolate Russia (35.20); Russia and China deepen ties – ‘read out’ of meeting between Sergei Lavrov and Wang Yi in Moscow (53.30).

25 February 2023

5 reasons why much of the Global South isn’t automatically supporting the ‘West’ in Ukraine.

25 February 2023

Western mainstream media declare ‘life expectancy of Ukrainians in Bakhmut is 4 hours’; discussion on actual Russian casualties (minute 10.00) followed by possible Ukrainian casualties; destruction of Ukrainian artillery (22.30 minutes); ‘peace plans’.

25 February 2023

NATO propaganda on Ukraine war one year later.

26 February 2023

Ukrainian fighters at Bakhmut reported encircled.

26 February 2023

West is out of touch with rest of world politically, EU-funded study admits.

United West, divided from the rest: Global public opinion one year into Russia’s war on Ukraine – report.

26 February 2023

Russia pincers close in Bakhmut; Zaluzhny warns Zelensky; More on Ukrainian and Russian casualties (27.00); China spooks west – Wang Yi’s meetings in Munich, read-outs, (51.50); CIA says Russia confident – report of the only proven meeting to have taken place between representatives of the US and Russia (60.30).

27 February 2023

Russia claims Bakhmut roads cut; Scholz and Macron mull ultimatum – but is this a cover for ammunition in NATO’s stockpiles?; Moscow warns of a declaration of war if Transnistria attacked (41.40).

27 February 2023

Professor Peter Kuznick on American secret history – Seymour Hersh and US History of Secret Operations.

28 February 2023

China reboots ‘no limit’ partnership with Russia.

01 March2023

Russia repels drones; Bakhmut to become a ‘cauldron’ for Ukrainians within 48 Hours; neocons (in two British mainstream newspapers) ‘double down’ (38.00); discussion on why China is becoming more vocal now (50.30).

01 March 2023

Douglas Macgregor: Ukraine will be destroyed.

01 March 2023

Military summary and analysis – second half a discussion on the next Russian mobilisation.

01 March 2023

Ukraine – a year later, US Department of Defence and State Department officials retreat into delusion.

01 March 2023

Colonel MacGregor: Ukraine has been destroyed and there’s nothing left. NATO membership is on the cards for Ukraine – which means, in effect, that there is no possibility of any negotiated settlement. Ukraine calls for US soldiers to be sent to the front.

02 March 2023

Ukraine, Russia, China and dealing with crazy people.

02 March 2023

The fiscal side of Europe’s energy crisis: the facts, problems and prospects.

02 March 2023

Early news about Ukrainian attack on Bryansk (Russia); Russia shrinks Bakhmut exit route; China greets Lukashenko (from Belorussia) in a grand manner (35.00); is China edging towards an anti-US alliance?

03 March 2023

Why Biden snubbed China’s Ukraine peace plan.

03 March 2023

At the brink of war in the Pacific? The nightmare of ‘Great Power’ rivalry over Taiwan.

03 March 2023

Macgregor – Nazis and corruption in Ukraine; failures of US ‘adventures’ in the recent past; no accountability for failure in the US military; Macgregor’s right-wing, anti-immigration etc., views; ‘NATO will crumble’.

03 March 2023

Grayzone – Nord Stream terrorism (07.00); Crimea (23.00); events in Ukraine (35.00); US and China – Taiwan, and using other countries and their populations to maintain US hegemony (43.00); US ‘progressives’ (58.20); Syria and sanctions – and the ‘progressives’ in favour of maintianing them (73.30); Sean Penn – a CIA mole? (84.00); anti-war protests worldwide (97.00).

03 March 2023

UK mainstream media reports the Russian taking Lupiansk (22.11); Russian air force becoming more active in bombing raids; Russian missile attacks on Ukrainian energy infrastructure – which also depletes Ukrainian air defence systems; Ukrainian ‘sabotage’ in Bryansk (44.50); US ‘hijacks and wrecks’ G20 (53.10).

04 March 2023 (originally posted 21 February 2023)

‘I am the President who delivers peace.’ [It sticks in the craw but included here out of interest.]

05 March 2023

The widening war: how the NATO-Russia confrontation is playing out in North Africa.

06 March 2023

The New Atlas – UK Ministry of Defence claims Russians fighting with ‘Shovels’ (08.50); Ukraine losing Bakhmut and low on artillery shells; Europe should convert to ‘war economy’ according to some EU ‘hardliners’; latest US military assistance package (16.00).

Russian reservists fighting with shovels – UK defence ministry. (BBC)

[The stories being published about the war in the Ukraine get more and more bizarre every day. If the Russian army is so badly equipped why are they winning the attrition war? If the Russians can take these highly fortified (prepared over a period of 7 to 8 years) towns, such as Soladar earlier in the year, and are winning – now accepted by more and more in the ‘mainstream media’ with just shovel wielding conscripts how pathetic does that make the NATO supported forces. The ‘journalist’ from the BBC was obviously aware of the ludicrous nature of this report as there is no byline. And if this is the quality of ‘intelligence’ coming from MI6 (which presumably is the source that provides the British Government with news from the front-line) then it’s no surprise that the British intelligence ‘community’ wasn’t on top of events that proceeded the Manchester Arena bombing. And if the Russians are sending troops into battle as suggested in this baseless crap, and simply pro-NATO/Ukraine propaganda, why are we being denied proof (photographic or otherwise) of these suicidal frontal attacks?]

06 March 2023

Wolf Richter: US natural gas production surges to record in 2022, up 33% from 2017. LNG exports hit record despite freeport terminal shutdown.

06 March 2023

America’s chips war with China: another sanctions backfire coming? [It’s starting to become more difficult to separate the events in the Ukraine with how the ‘west’ is acting in relation to China.]

06 March 2023

Russia claims Bakhmut ‘cauldron’ and 10,000 troops trapped; first NATO Leopard tanks to be used in Bakhmut?; west media admits Ukraine losses, blames Zelensky

06 March 2023

Ukraine is going to lose.

06 March 2023

Military summary and analysis. [Includes a speculative discussion about whether the Ukraine is using its defence of Bahkmut with inexperienced troops as a blind to build for a Spring offensive further south.]

07 March 2023

Wall Street Journal: ‘US is not yet ready for Great Power conflict’ yet still plots against China.

07 March 2023

Ukraine denies involvement in Nord Stream pipelines blast. [More irrational reporting from the BBC. And I deny any link to the Brink-Mats gold heist – but then no one accused me of being involved in the first place. This is just a screen to take the ‘heat’ off the US state terrorists. And in all the ‘debate’ about this non-news there’s no mention whatsoever about Seymour Hersh’s report, published earlier this year, that accused the US and Norway of planning and carrying out this terrorist act.]

07 March 2023

Russia presses Bakhmut ‘cauldron’; Zelensky vows Bakhmut defence; Ukrainian losses and inexperience (24.30); possible Ukrainian and Russian Spring offensives (37.21); Ukraine’s lack of infantry (44.50); Shultz in Washington for one hour meeting with Biden – and then back home (50.10).

08 March 2023

‘How stupid do they think we are?’ Nord Stream pipelines bombing edition.

08 March 2023

Douglas Macgregor – Russian methods of warfare.

08 March 2023

US General talks up war against China by 2025.

08 March 2023

Russia captures East Bakhmut; Zelensky admits strategic importance of Bakhmut (01.30); Intel: Nord Stream attack 6 guys and a boat (31.00); the limits of US power (60.00).

09 March 2023

The Financial Times’ Martin Wolf worries about Europe’s future.

09 March 2023

Georgia protests: US seeks to open 2nd front against Russia. [Listing other examples of where the US has interfered in the internal affairs of countries that follow a political line not in accord with US wishes.]

09 March 2023

Neocon fanatic Anne Applebaum confronted on Ukraine – a piece from the Grayzone’s longer piece published on 03 March 2023 – posted above.

09 March 2023

A feminist demand on International Women’s Day: Fire Victoria Nuland.

09 March 2023

Russian missile strike – using hypersonic missiles for the first time; failed Ukrainian counter-attack in Bakhmut; a different analysis of the Wager force by the Ukrainians (14.30); uncontrolled Ukrainian retreat; Financial Times criticises Ukrainian tactics in Bakhmut; 6 guys and a boat and Nord Stream terrorist attack (38.00); Haines, Director of National Intelligence sabre rattles against China(41.30); China’s Foreign Minister, Qin Gang, warns of coming conflict with the US at press conference (48.30).

Qin Gang meets the press: summary and full text.

10 March 2023

The Grayzone live – Nord Stream cover ‘story’ (03.00); Zelensky not invited to the Oscars, Ukrainian Nazis, (26.00); ethnic cleansing of Russians in Ukraine (31.05); US Democrats use McCarthyite tactics against journalist (45.00); Twitter files (77.00); the situation in Syria (86.00).

10 March 2023

Rashida Tlaib [of the so-called ‘progressive squad’ in the US Democrat Party] confronted about sending $100 Billion to Ukraine – and the general pusillanimity of the US democratic ‘left’. Jimmy Dore.

10 March 2023

Military summary and analysis. Any Ukrainian counter-offensive in Bakhmut suicidal? Bakhmut going to be biggest battle of 21st century – so far. What’s behind the argument between Prigozhin (of the Wagner Group) and the Russian Ministry of Defence?

10 March 2023

Ukraine counter-attack in Bakhmut; China linking arms to Russia to Taiwan; Russia sending SU35 aircraft to Iran.

11 March 2023

The New Atlas live – Russian missile campaign in Ukraine, respective casualties (02.00); Georgia street demonstrations (17.30); Taiwan (27.30); Nord Stream terrorist attack (53.00); Q+A (65.00).

11 March 2023

Russia in Bakhmut Centre; Kinzhal hypersonic missiles spook Kiev and the west; Nord Stream terrorist attack by 6 people in a yacht (38.00); China achieves a huge political coup as Iran and Saudi Arabia reconcile, Russia to supply aircraft and air defence systems – but all but ignored by the western mainstream media (43.00).

12 March 2023

Military summary and analysis.

13 March 2023

Bankruptcies soar across EU as companies hit wall at fastest rate since records began in 2015.

13 March 2023

Russia advances in Bakhmut and Slaviansk; Ukraine delays counter-attack; for the Kremlin there’s only a military solution; banking crisis hits US. [Time stamps can be found under disndat1000 in comments.]

13 March 2023

John Mearsheimer – the U.S. is destroying Ukraine.

13 March 2023

US ‘Imperial anxieties’ mount over China-brokered Iran-Saudi Arabia diplomatic deal.

13 March 2023

Different approaches to ‘foreign agent’ laws – depending if whether ot not you’re the US

EU may introduce ‘foreign agents’ law.

Echoes of Maidan: Georgia has a huge Western-funded NGO sector and regular outbreaks of violent protest, is there a link?

West blasts Balkan region’s plan to replicate US law.

Four views on the present (or is it best to say systemic?) banking crisis

13 March 2023

Why the banking system is breaking up.

13 March 2023

Silicon Valley Bank’s collapse shows little has changed for big banks since 2008.

13 March 2023

Silicon Valley Bank: how interest rates helped trigger its collapse and what central bankers should do next.

14 March 2023

Why central banks are too powerful and have created our inflation crisis – by the banking expert who pioneered quantitative easing.

14 March 2023

West mainstream media (Washington Post, Daily mail, Wall Street journal) pessimistic about the deteriorating situation of Ukraine (08.00); Russia advances in Bakhmut; Ukraine losses mount; doubts over offensive grow; Rissian economy (43.00)

15 March 2023

Rosneft refinery in Schwedt continues to be a microcosm of Europe’s sanctions-induced energy mess.

15 March 2023

Why China is unlikely to invade Taiwan.

15 March 2023

Jeffery Sachs – the United States is a madman.

16 March 2023

The not-so-winding road from Iraq to Ukraine.

16 March 2023

Washington’s downed drone and growing admissions of Ukraine’s military deterioration.

16 March 2023

Russian forces capture southern Bakhmut.

17 March 2023

Bakhmut ties Russians as Ukrainians prepare for the next counter-offensive. [A very much pro-Ukrainian analysis – which takes all its ‘information’ by unsupported Ukrainian government sources. Seems to go against all other commentators analyses and doesn’t accept the idea that the Russians are following their strategy of gradually eliminating Ukrainian force (both in men and material) rather than gaining land. Included here to see how valid the conclusions might become as matters pan out in the next couple of months.]

17 March 2023

How Microsoft is becoming more and more embroiled in the conflict in the Ukraine.

18 March 2023

The Iraq War 20 years on: end of the US’s post-9/11 neoconservative dream

18 March 2023

The illegal invasion of Iraq: never forget.

18 March 2023

Finnish PM honors ultra-right Ukrainian militant.

19 March 2023

US threatens to arrest ICC judges if they pursue Americans for Afghan war crimes. [An article first published on 10th September 2018. It seems that if the International Criminal Court ‘threatens’ the US or any of its allies then it is ‘unaccountable’ and ‘illegitimate’ but the opposite if it makes rulings against the ‘enemies’ of the west.]

19 March 2023

Anti-China propaganda dismantled on BBC.

Economist, policy analyst and Columbia University professor Jeffrey Sachs appeared on BBC in April 2021 to talk about international cooperation on climate change and instantly pushed back against the host’s framing of China as a rampant human rights abuser while letting the U.S. off the hook for minor offenses like the war in Iraq, Guantanamo and the CIA torture program. Sachs also challenged the host’s suggestion that Sachs was appearing as a stand-in for the United States government, a proposition he vehemently denied.

20 March 2023

Arresting Putin – or arresting all-out Western public revolt?

20 March 2023

Fiona Edwards speaking on behalf of No Cold War Britain at the NO2NATO NO2WAR Rally in London on 25 February 2023. [Video.]

21 March 2023

On the ICC, Putin, Netanyahu and Prosecutorial Discretion.

21 March 2023

Britain supplying depleted uranium rounds to Ukraine.

21 March 2023

The hidden proxy war Washington wages against China.

21 March 2023

Ukraine says Russian missiles destroyed in Crimea. [This claim was never verified and the story just disappeared from the ‘news’. The BBC, again, taking Ukrainian claims at face value without any attempt at verification. This is propaganda not news!]

21 March 2023

Banking crisis, de-dollarization and US Wars – a wide ranging discussion on the present financial ‘crisis’. Russia, due to sanctions, is immune from the banking problems in the collective west; bankers doing the same as in 2008 – banks ‘to big to fail’; effects of sanctions on Russia, incompetent financial policy in west, sequestration of Russian assets make other foreign ‘investors’ reluctant to invest in US Treasury Bonds; the market was going up during the pandemic ‘when the markets were closed’; 49.00 min., the start of the Petrodollar – but now the US is not a dependable partner; how Russia and China are different ‘friends’ than the US; why trust any of the old colonial ‘masters’ against Russia or China?; war to come with China in order for the US to get out of its financial mess; 75.00 min., explanation of derivatives market.

22 March 2023

Colonel MacGregor: The Gathering Storm in Ukraine spells doom for the West. [Includes, at the end, a video discussion the final part of which addresses the incident of the US drone that crashed into the sea off the coast of Crimea.]

22 March 2023

Send in the clowns.

22 March 2023

Depleted uranium to Ukraine. Putin and Russia forced to react. Lavrov, this will end badly for UK. Alex Christoforou. The UK government always first in line to escalate matters on the international scene. [Video podcast.]

22 March 2023

UK defends sending depleted uranium shells after Putin warning. [The normal uncritical response from the BBC.]

22 March 2023

Russia presses on Bakhmut and Avdeevka; Russia furious about UK supply of depleted uranium shells along with Challenger tanks; speculation on the situation of the production of armaments in Russia; China-Russia Mutual Defence Pact.

23 March 2023

What Europe got wrong about sanctions on Russia.

23 March 2023

West surges ammunition ahead of Ukraine’s all-or-nothing offensive; FT article admits problems in expansion of artillery shell production (18.00); US/NATO/EU/UK to deplete their own strategic reserves?; UK Telegraph article claims Russia not able to produce sufficient shells – but with no proof (23.26).

24 March 2023

The Nord Stream Cover-up – Seymour Hersh

24 March 2023

Slovakia offered US helicopters for giving jets to Ukraine.

24 March 2023

New Atlas Live: Ukrainian offensive; west giving Ukraine the illusion of support; UK supplying depleted uranium shells – for just 14 tanks, perhaps because that’s all they have so sending in desperation, and potentially polluting the country they are supposed to helping (in agricultural areas) with toxic chemicals; economic and social problems in the EU – regime change in the west rather than Russia?; Russia and China just waiting for the west to collapse?; AUKUS – and Australia buying nuclear powered submarines to defend their own country or to join the US/UK offensive against China?; what is real GDP/; who is buying US bonds any more?; west form over substance.

24 March 2023

Douglas Macgregor: Zelensky has thrown thousands of Ukrainian troops into the Bakhmut bloodbath – a horror story on the levels of WWI. Where will the soldiers come from to carry out the so-called ‘Ukrainian spring offensive’?

24 March 2023

Ukrainian counter-offensive ‘will shock the world’ – US adviser.

25 March 2023

NATO carried out ‘inhumane experiment’ in Balkans – health minister. [Now the UK plans to do something similar in the Ukraine.]

27 March 2023

End of unipolarity with Jeffrey Sachs, Alexander Mercouris and Glenn Diesen. [This writer is not such a big fan of ‘multipolarity’ as some – especially those on the ‘left’ who consider the People’s Republic of China still to be a socialist country. However, this discussion is included here for a little bit of historical context and also to illustrate the death of the present day world’s ‘hegemon’ – the USA.]

27 March 2023

Tactics, arms and ammunition: What will shape Ukraine’s offensive and the impact of its aftermath.

27 March 2023

Tensions rise in Crimea as Russia prepares for a likely spring offensive. [This is yet another ‘academic’ analysis which seems to go against all readily available information – other than that available from Ukrainian or western sources. Included here to see what happens in the next few weeks. I predict this argument will be conveniently forgotten as the Ukrainian forces descend into a debacle and chaos. But …. We shall see.]

27 March 2023

Ukrainian soldiers seen with depleted uranium ammo in UK.

28 March 2023

The Critical Hour: talking US-Russian tensions in Ukraine and US-Chinese tensions over Taiwan. ‘There seems to be no standard, no law which the United States will not ignore and break and then deny so long as it furthers its objectives’.

28 March 2023

Russia more Bakhmut gains, taking Azom industrial area; Russian aircraft bomb Sumy; missiles targeting Kiev; speculation that Kiev unable to attack Crimea with missiles but might use Taiwan bought drones instead; Ukraine still short of ammunition and tanks; opposition in Ukraine to the use of UK supplied depleted uranium shells on Ukrainian soil; analysis of munitions situation in Ukraine by Chinese commentator; China stonewalls Xi-Biden talks, as well as Zelensky speaking to China.

28 March 2023

Russia negotiates PEACE between Saudi Arabia and Syria!

28 March 2023

Here’s why Human Rights Watch deliberately only scratched the surface in exploring Ukraine’s use of banned ‘petal’ mines.

28 March 2023

UK Army putting ‘outrageous spin’ on depleted uranium science.

29 March 2023

The anniversary of the March 2022 sabotaged (the the US and the UK) peace accord arrived at in Istanbul; the escalation of the conflict with the supply of more and more materiel to Ukraine in order to achieve the wished-for ‘collapse’ of Russia and the fall of Putin; what’s really needed for an effective counter-offensive; the historical danger of being a proxy for the United States – they lose their independence; Russia speeds Bakhmut advance; Russia strikes Ukrainian rear; Ukraine shells Melitopol; divisions in the Ukrainian structure over the impact of the loss of Bahkmut; Russian weapons output; any Ukrainian counter-offensive will be the last call for Ukraine.

30 March 2023

What Ukraine needs to learn from Afghanistan.

30 March 2023

US issues NATO weapons playing cards to help Ukraine avoid friendly fire. [A bizarre article with some wild assertions – but gives an indication of the problems of the pick-and-mix military equipment which is being supplied to the Ukraine.]

30 March 2023

Russia to offer food for North Korean weapons – US. [Another link included here as it is just another part of the strange and wonderful world of western propaganda. No ‘facts’ are presented to substantiate the argument and there are no ‘facts’ on the ground that indicate that Russia is in urgent need of weapons in its war against the Ukraine. Like many stories over the past year this one will, more than likely, just peter out.]

30 March 2023

Russia storms Central Bakhmut; Kiev and the US in denial; Zelensky depressed; Putin upbeat on the economy; EU to prolong cutback in natural gas use.

30 March 2023

Military summary and analysis – statement about destruction of NATO bunker, with the loss of mainly UK and Polish troops (08.00).

30 March 2023

‘Significant portion’ of £4.8bn UK lethal aid for Ukraine will remain secret.

30 March 2023

UK ‘unaware’ of Russia firing depleted uranium in Ukraine – while the British military is supplying toxic ammunition to Ukraine, it lacks evidence Russia has already used it in the conflict.

31 March 2023

It’s not Russia that’s pushed Ukraine to the brink of war – an article originally published on 30 April 2014 when the Guardian took a different point of view about the conflict.

31 March 2023

Indictment strengthens Trump; Ukraine admits Russian gains in Bakhmut; China rejects EU pressure for talks with Zelensky; who has the ‘best’ technology, the west or the the Russians?

31 March 2023

The Grayzone Friday Live – the Trump indictment (04.00); the Azov battalion and the Ukrainian fascists and their international hangers-on (31.00 min.); the International Criminal Court arrest warrant for Vladimir Putin and ‘children camps’ in Russia 41.00 min.; OPCW cover up of the supposed Syrian government chemical attack in Duoma (81.00 min.); the continued US occupation of the oil and wheat region of NE Syria (96.00 min.)

31 March 2023

Ukraine’s End Game approaches but more war may come.

31 March 2023

Once the Dollar loses Reserve Currency Status – there’s NO GOING BACK.

02 April 2023

International Criminal Court [ICC] irreversibly crosses the line of legal decency.

03 April 2023

The ‘Battle of Bakhmut’ – and Russian efforts to ‘grind down’ Ukrainian forces, where the intention is to minimise Russian losses whilst maximising Ukrainian casualties, in both manpower and weaponry; the supposed Ukrainian ‘counter-offensive’; the inability of the west to maintain the necessary level of military supplies; estimated Russian casualties (05.30); Russia’s GLONASS-Guided Glide Bombs (10.00); and Ukrainian air defence capabilities and the efforts of the Russians to destroy its infrastructure.

03 April 2023

Military summary and analysis. The Russians have caught the terrorist in St Petersburg. Bakhmut is now Artemovsk. Ukrainian missile attack in Melitopol.

03 April 2023

Russia captures central Bakhmut and raises flag over Town Hall; Russia outraged by Tatarsky murder in St Petersburg (32.00); expulsion of Orthodox monks from Kiev monastery (44.00); Saudi cuts oil output (47.30); and the disintegration of the oil price cap.

04 April 2023

First Russian shipment of (allegedly) diesel docks in Mexico since G7 Plus-imposed price cap, stoking controversy and confusion.

04 April 2023

The tragic U.S. choice to prioritize war over peacemaking.

04 April 2023

The Government is refusing to tell the public how billions worth of ‘lethal aid’ for Ukraine is being spent.

04 April 2023

Depleted uranium accident file censored – the government is hiding a paper on the ‘worst credible accident’ involving ammunition Britain has supplied Ukraine.

05 April 2023

US forces under fire in Syria: illegal occupation enters dangerous phase.

06 April 2023

Waiting for that too-much-discussed Ukraine Counter-offensive.

06 April 2023

Douglas Macgregor and Andrew Napolitano – what’s happening in the Ukraine at the beginning of April 2023.

07 April 2023

Telegram leak of US/NATO document paints grim picture of condition of Ukraine’s military.

09 April 2023

Europe must resist pressure to become ‘America’s followers’, says Macron.

09 April 2023

Ukraine’s coming offensive: leaked NATO plans and lack of arms.

10 April 2023

Pushilin visits Bakhmut; Ukraine suffers heavy losses; Ukraine air defence weakened; UK hints war may be lost.

10 April 2023

Pentagon in panic as second set of leaked documents gains traction, revealing spying on Allies and deteriorating Ukraine capabilities.

11 April 2023

Refugees from Ukraine recorded across Europe. [Note the large percentage of refugees who are in the Russian Federation or Belarus.]

11 April 2023

Pushilin claims Bakhmut advances and Marinka gains; Pentagon thinks Ukraine only capable of modest gains in any future ‘offensive’.

11 April 2023

U.S. intel leak reveals 50 elite British troops in Ukraine.

12 April 2023

Leak shows Western special forces on the ground. [The BBC reports it – will they pursue the issue and question the legality of their presence or just explain it away?]

12 April 2023

Ukrainian air defenses dwindling, West scours world for arms on eve of ‘Spring Offensive’.

12 April 2022

Prigozhin and Russian Ministry of Defence say priority is to resolve the conflict in Bakhmut; high casualties amongst western ‘mercenaries’; Russian air force active around Bakhmut; Russia claims it has captured the Marinka factory area; Crimea ready for ‘anything the Ukrainians throw at them’; Putin: Russian Economy Surging

12 April 2023

James K. Galbraith: The gift of sanctions – an analysis of assessments of the Russian Economy, 2022 – 2023.

12 April 2023

Ukraine Firepower v Russian Firepower, with Scott Ritter – leaked Pentagon briefing papers; seven to one kill ratio; Austin lying to Congress; Zelensky ‘out of his mind’ when he talks about Crimea; CIA using journalists as spies in Russia.

12 April 2023

Kiev votes to name street after WW2 Waffen-SS commander.

12 April 2023

Zelensky and team stole at least $400 million of US aid – Seymour Hersh.

13 April 2023

Russia repels Bakhmut counter-attack; Kiev postpones ‘offensive’; US ‘borrows’ shells; Brazil and China ditch USD in bilateral trade; Saudi Arabia defies the US and receives Syrian Foreign Minister.

13 April 2023

Pentagon leaks paint gloomy picture of long war that can’t be won but must not be lost. [This ‘academic’ – after months of just doling out Ukrainian government propaganda – starts to report the reality, but still will unproven and unsubstantiated claims about Russian casualties. As always, follow the money.]

14 April 2023

Larry Johnson and other former insiders debunk Air Guardsman-as-Pentagon-Leaker story as press cheers arrest – ‘six guys in a boat’ Part II.

14 April 2023

New Atlas LIVE: unrelenting Russian attacks in the Ukraine; the west talking sense after a year of misinformation; Germany shows it even more subservient to US interests; EU delegation to China treated exactly the same as any other foreign visitor; the perversion of the Dalai Lama; BBC complains about being described as being ‘state funded’.

14 April 2023

UK Ministry of Defence [interesting that western ‘information’ outlets are now seemingly following the reality on the ground – the question is ‘Why are they now telling the ‘truth’ when they have been lying for months?’ Everything is full of contradictions.]; Prigozhin’s estimate of Ukrainian casualties in the defence of Bakhmut; Ukraine retreats from Bakhmut, Russia advances Avdeyevka; US arrests ‘leaker’ – a young 21 year old; Hersh on Ukraine corruption.

15 April 2023

Russia leaves neoliberal ‘West’ to join world majority.

15 April 2023

Russia captures two Bakhmut districts; Prigozhin taunts Zelensky (15.30-25 min.); analysis of Ukraine’s ‘counter-offensive from what was revealed in the Pentagon documents leak – including thoughts of a British mercenary published in The Spectator (25-55 min.); Bloomberg casts doubt on a Ukrainian advance in 2023.

15 April 2023

Scott Ritter: NATO can’t do anything – following the fall of Bakhmut and the unravelling of the Ukrainian army. With an analysis of changing Russian tactics of its air war.

15 April 2023

Why the media don’t want to know the truth about the Nord Stream blasts.

15 April 2023

Is the Army all that you can be?

16 April 2023

The increasing number of trial balloons for Polish intervention in Ukraine.

16 April 2023

EU rejects Ukraine grain bans by Poland and Hungary. ‘Friends’ fall out.

17 April 2023

US rushes to provoke war with China over Taiwan, US think tanks admit Taiwan will be destroyed in whatever scenario. [It’s now becoming impossible to separate what happens in the Ukraine with that is developing in China/Taiwan.]

17 April 2023

Tracking the EU decoupling from Russia.

18 April 2023

Putin tours battlefronts and meets top commanders; Russia’s massive aerial bombing; Eastern European countries reject Ukrainian grain; ‘Global South’ continues to avoid supporting the ‘west’ in its conflict with Russia.

19 April 2023

Ukraine’s offensive: taking territory vs. the war of attrition.

19 April 2023

The official story of the Ukraine war grossly misleads.

20 April 2023

Leaks reveal reality behind U.S. propaganda in Ukraine.

20 April 2023

Russia advances on key Bakhmut Road; West splits on negotiations; reasons for the ‘counter-offensive’ from the interested players; west depending upon an internal collapse of both the Russian military and political structure; how the ‘leaked’ Pentagon Papers are being manipulated from all angles.

20 April 2023

U.S. Sends Troops To Taiwan! – even though the US officially recognises Taiwan as part of China under the acceptance of the ‘one China policy’.

20 April 2023

EU state [Latvia] bans WW2 victory celebration.

20 April 2023

Facebook labels Seymour Hersh’s reporting ‘false’.

21 April 2023

Ukraine conflict highlights key question for Africa: should we focus on the problems of the elite or those faced by the majority of the population?

21 April 2023

The Critical Hour: US sells 400 harpoon anti-ship missiles to Taiwan; update on Ukraine fighting – with Brian Berletic.

21 April 2023

New Atlas LIVE: US builds consensus for war with China and closer look at Taiwan with Carl Zha.

21 April 2023

Russia claims Bakhmut road cut; Ukraine troops caught in a true ‘cauldron’ in Bakhmut; G7 Russia blockade as Russia economy surges (22 min.).

21 April 2023

Did Russia destroy a deep underground bunker in March – complete with high Ukrainian officers and also numerous representatives from different NATO countries?

21 April 2023

Ukraine can retake Crimea within months, if we let it. [Another so-called ‘expert’ living in a fantasy world.]

22 April 2023

Road cut and encircled in Bakhmut; Kiev complains on lack weapons replenishment; General Ben Hodges lives in cloud cuckoo land – see article immediately above; Yellen’s arrogant, aggressive, condescending and paternalistic approach towards China (46 min.) and China’s response (54 min.); the present Sudan conflict and US interference.

23 April 2023

Ukraine shells Donetsk, killing multiple civilians.

23 April 2023

Biden told CIA to lie about Hunter Biden laptop.

24 April 2023

Russian air power over Ukraine increasing and more shortcomings appear ahead of the much awaited Ukrainian ‘counter-offensive’.

24 April 2023

The Russians are winning too slowly! And are the Poles going to send in troops against the Russians?

24 April 2023

Tucker Carlson has been fired.

24 April 2023

Dozens of foreign mercenaries killed in Iskander strike.

24 April 2023

Liberal media won’t cover FBI raid on black Socialists – for speaking out against the Ukrainian proxy war.

24 April 2023

Ukrainian commander laments state of army – El Pais.

24 April 2023

‘Crazy’ that Russia and Ukraine still trade – Seymour Hersh.

24 April 2023

War, what is it good for? [OK – until the very last few paragraphs where he loses the plot.]

25 April 2023

Is Zelensky’s international charm offensive, backed up with US bullying, finally paying dividends in Latin America?

25 April 2023

The empire of hypocrisy.

25 April 2023

The reality of war in Ukraine.

26 April 2023

Military summary and analysis. Bakhmut is in the cauldron. Nevelske has been encircled.

27 April 2023

Ukraine war changing the face of Europe with Alastair Crooke.

27 April 2023

Ukraine still holds 7.5% of Bakhmut; Ukrainian counter-offensive ‘inevitable’; BBC article admits Ukraine is exhausted and out of ammunition [see below]; the success of the Russian in ‘bleeding’ Ukraine of men and material; did Ukraine attempt to assassinate Putin?; Xi-Zelensky phone call, where Xi states that sovereignty also applies to Taiwan [Global Times editorial below].

Bakhmut defenders worry about losing support. [BBC article referred in the podcast above.]

Xi’s call with Zelenskyy demonstrates responsibility of a major country.

28 April 2023

Russia rains down missiles – and how this is a continuation of the Russian tactic to degrade the Ukrainians air defence system; Lavrov at the UN on Israel-Palestine; Turkey blames US/EU collapse grain deal.

29 April 2023

The Critical Hour: Growing doubt over Ukraine’s offensive and US difficulties recruiting new soldiers.

29 April 2023

UK: west must double down even if Ukrainian offensive fails; Medvedev: Russia will go for full victory.

29 April 2023

Military summary and analysis. A fierce battle for the south of Ukraine is about to begin. [With an interesting – and new, at least for me – presentation about the role of the Russian navy in any upcoming offensive and how the west might seek to mitigate its effectiveness.]

29 April 2023

The Grayzone live; end of the Tucker era; US Democratic ‘left’ just accepting Biden’s re-election bid; US involvement in the present crisis in Somalia; Lloyd Austin lies to Congress about the vitality of the Ukrainian forces and effectively using the Ukrainian population as cannon fodder; ;

30 April 2023

Ukraine hold only 6% of Bakhmut; Ukrainian tactics in the conflict with Russia being determined by political aims, here the idea to ‘spoil’ the Victory Day celebrations in Russia on 9th May; Russian bombing intensifies; dilemma that Ukraine has about where to deploy their depleted air defence systems; UK mass media express doubts about the viability of the long awaited Ukrainian spring/summer ‘counter-offensive’; a Polish general has similar doubts; and that live is being ‘forced’ to attack’ – even though totally unprepared, the Xi-Zelensky phone conversation (which took place in the Russian language) – unbeknownst to the US.

01 May 2023

Why is the US wiring Ukraine with radiation sensors to detect nuclear blasts?

01 May 2023

Russian missile hit ahead Ukraine offensive and Kiev’s obsession over territory amid war of attrition – with suggestions about how Russian defences anticipate the Ukrainian ‘counter-offensive’.

01 May 2023

Missiles strike Pavlograd; economic distortions caused by foreign ‘aid’; Ukrainian military admit – in the western media – that they are not ready for the so-called ‘counter-offensive’; US military: Russia more powerful now; would Ukraine actually consider an attack on the Russian mainland?; Biden looks for way out.

01 May 2023

Is the US narrative on Ukraine War changing? Ray McGovern. A discussion about the consequences of the recent leak of Pentagon documents.

01 May 2023

Will the EU sanction Russia’s nuclear industry?

01 May 2023

The single dumbest thing the Empire asks us to believe.

01 May 2023

The proxy war in Ukraine is an imperialist adventure.

02 May 2023

More than 20,000 Russian troops killed since December, US says. [The BBC publishes this as gospel even though the release of the ‘Pentagon Papers mark 2’ earlier in the year had proved that the US has been lying all the time in respect to the war in the Ukraine and that their statistics were only published for strategic, political aims. In this article the BBC doesn’t even question the veracity of the numbers and merely adds its normal, pathetic disclaimer; ‘The BBC is unable to independently verify the figures given’ adding, in this case, ‘and Moscow has not commented’. But then why should Moscow comment on fabrications? Neither the US nor the BBC show any evidence to back up these figures.]

02 May 2023

What happens if the west decides to negotiate an end to the war in Ukraine and Russia does not (really) go along?

02 May 2023

Ukraine counter-attack in Bakhmut fails; angry attack by Prigozhin (of the Wagner group) on the Russian Ministry of Defence [this is a bizarre situation in the middle of an important battle of an ongoing war – is this just a ruse to blind side the Ukrainians and their western allies?]; Kirby bizarre statement on Russia losses and Milley calls Zaluznhy – is this to push for even a disastrous Ukrainian offensive? (20-42 mins.)[see the BBC link above]; Sullivan industry hollowed out.

02 May 2023

What China is really playing at in Ukraine.

03 May 2023