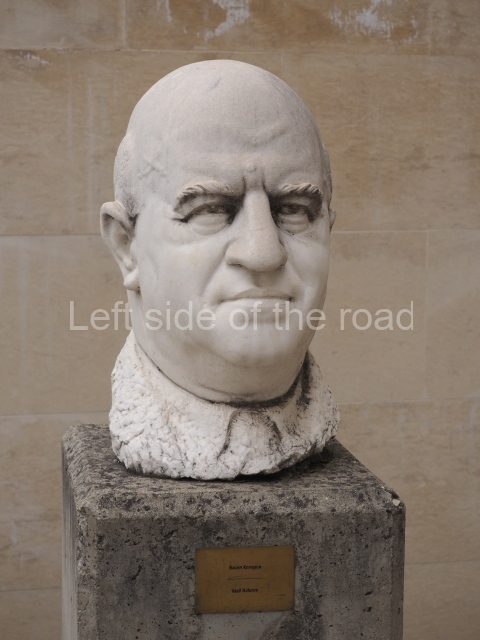

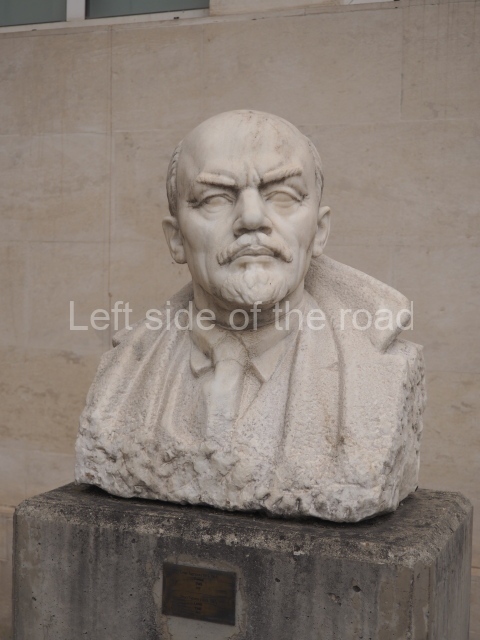

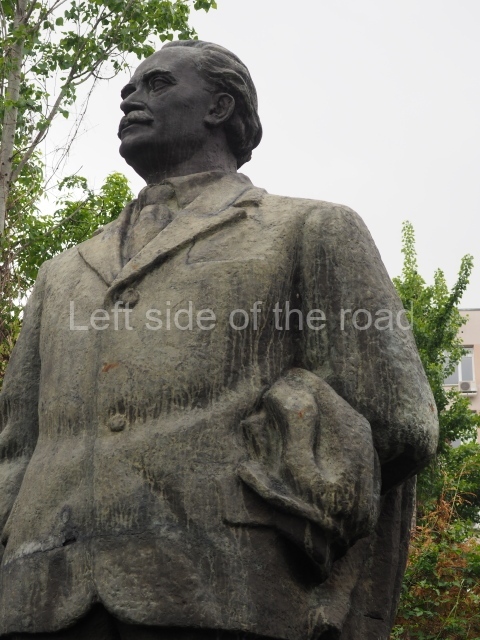

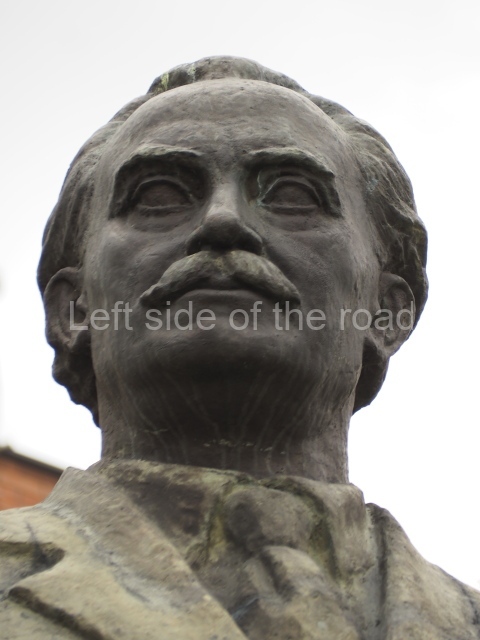

Tribute to Enver Hoxha – on the occasion of the 40th anniversary of his death

by Gjon Bruçi, Gazeta DITA, April 11, 2025

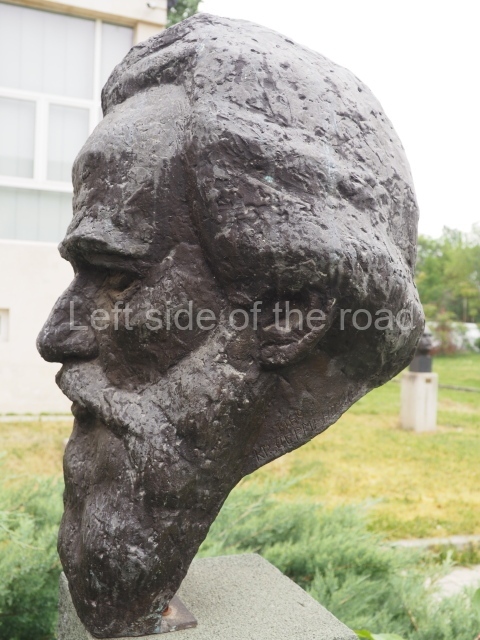

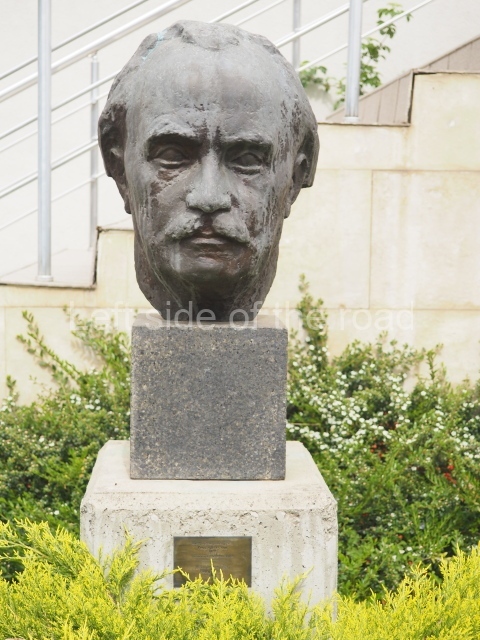

April 11, 1985 – Albania held its breath, lowered its flag and put on mourning clothes. The Leader had died – the National Pride, the Renaissance figure of modern times, the greatest man in the history of the Albanians, Enver Hoxha.

But who was Enver Hoxha? A communist? A partisan? A commander? A commissar? A leader of the people? A strategist and reformer? A legend? Or a truth?

‘History is made by the masses, individuals play a particular role’ – so teaches the history of human society. But Enver Hoxha’s role in the 50-year era of the new and modern Albania was immense. He embodied, in a single person, the highest and most refined virtues of the Albanian, while at the same time being the most brilliant fulfiller of his people’s aspirations.

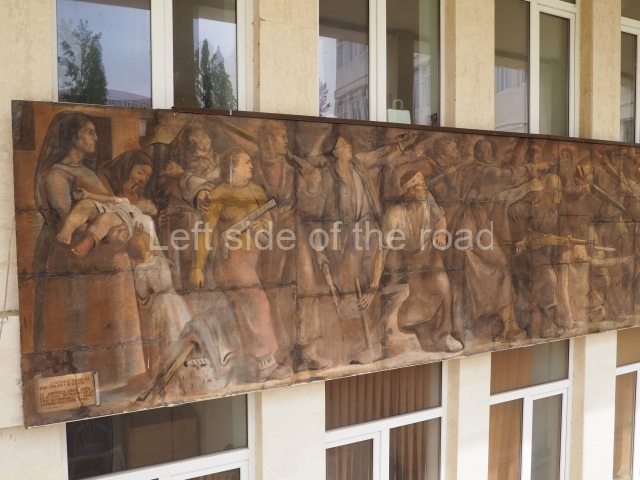

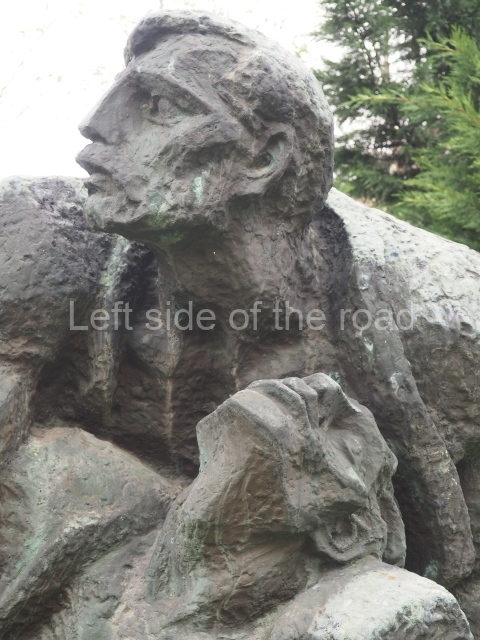

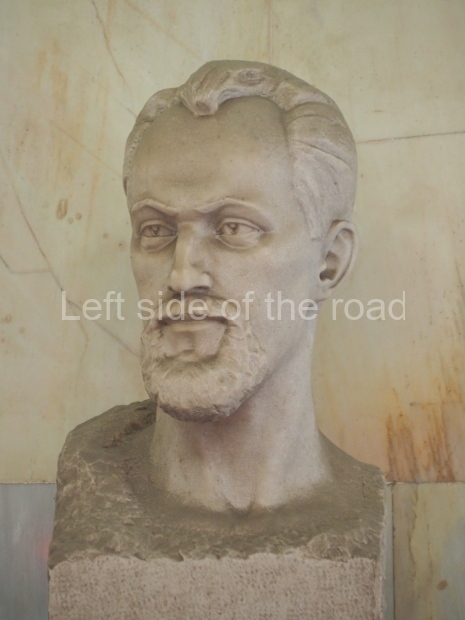

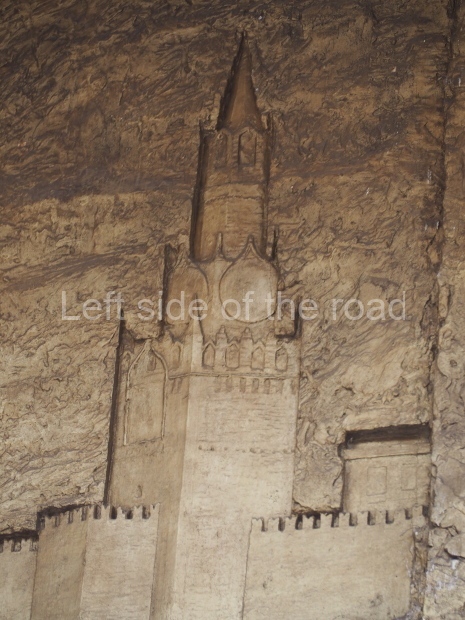

In two thousand years of the New Era, the Arbër people produced dozens and hundreds of giants of both intellect and the sword. Among them shone the Hero of the Nation Gjergj Kastrioti-Skanderbeg. He was granted many titles by the chanceries of the time, such as: ‘Prince of Arbër,’ ‘Iskander,’ ‘Knight of Christ,’ and others. But his people called him with simple words – ‘The Bravest’ and ‘The Leader.’

Five hundred years later, Arbër – now Albania – would once again have its Heroes of the pen and the rifle, of thought and action, of movement and revolution, who stood up for the homeland in its most critical moments. Among them, like a mountain eagle, rose the Glorious Leader Enver Hoxha. Time gave this National Hero dozens of titles too, but the people who loved him so deeply simply called him ‘The Commander’ and ‘The Man of the Land.’

Writing about Enver Hoxha on a memorial anniversary is as easy as it is difficult. It is easy, because his monumental deeds are still alive – not only in the minds and hearts of us, his contemporaries, but also because, despite the slander of the bourgeoisie and its mercenaries, they rise like mountains and shine like the sun across the Albanian horizons and beyond. At the same time, writing about Enver Hoxha is extremely difficult, because our writings, no matter how beautifully crafted, cannot capture – in either quantity or quality – the work and legacy of this Colossus of Communism, this Great Man of Albanianhood. That is why I will attempt to focus only on two or three of the most significant moments of our unforgettable Commander and Commissar – moments which, when viewed today through the lens of time and the events we are experiencing, take on multiplied value, a value that exceeds the dimensions of an ordinary leader’s life and work.

Enver Hoxha was the most authentic embodiment of the well-known Albanian expression ‘The Man of the Land.’ To earn this title requires many qualities and high virtues that set a person apart from ordinary people. Among other things, to be or become such a man, one must possess wisdom, bravery and the courage of true men. These qualities – along with many others – Enver Hoxha possessed to the highest degree.

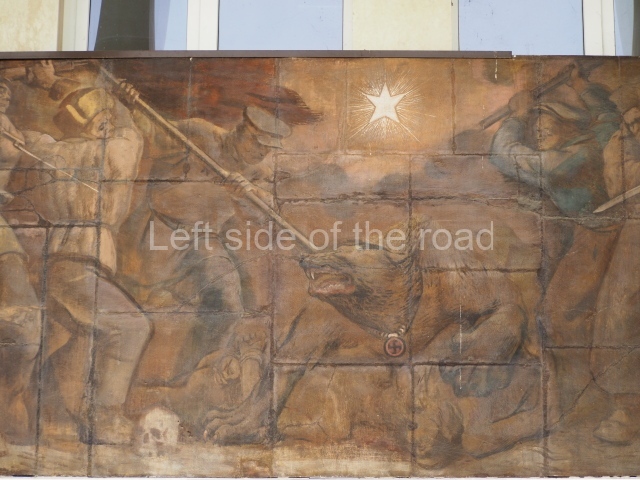

It was the harsh winter of 1943. In the mountains of Çermenika, the General Staff of the National Liberation Army was in a critical situation. The routes leading to the free zones were blocked by snow and by German and Ballist forces. British General Davies, who was stationed as an ally near the General Staff, was terrified by the dire conditions. In a debate with Enver Hoxha, he urged him to halt the war and surrender:

‘Mr. Hoxha, you’re mistaken… you’ve lost the war… you’re surrounded… you have only two options: either be killed or surrender…’

Enver Hoxha, who had been trying to calm the British ally, exploded when he heard those defeatist words:

‘Who lost the war? Who should surrender? Never! You, Mr. General, are a defeatist and a capitulator. The Albanian partisans do not know defeat, let alone surrender. They know only resistance and victory!’

And it was Enver Hoxha’s unmatched courage – his absolute conviction in victory – that led the General Staff of the National Liberation Army out of that fierce German-Ballist siege, during that unforgettable cold of late December 1943.

In 1946, at the Paris Peace Conference, the outcomes of the Second World War were being finalized. The great victors – the United States, the Soviet Union, the United Kingdom and France – held the primary positions and were deciding the fate of nations. Little Albania, with fewer than one million inhabitants, arrived at this Conference with its head held high. Its contribution to the Anti-Fascist War, compared to its human and material capacity, was of the highest level. But neighbouring chauvinists refused to acknowledge this fact. The Greek representative at the Conference, Caldarisi, launched a storm of accusations against Albania, labelling it a collaborator of fascism in the attack against Greece. If these accusations were accepted as truth, then the territorial integrity of newly-liberated Albania would be called into question. As always, the great powers of the world had little concern for the fate of small countries and peoples. These could be traded among them, like gifts or relics exchanged at a simple celebration. Facing this potential threat to our country was Enver Hoxha. With unmatched courage, he declared at the Conference:

‘I solemnly declare that: Neither the Paris Conference, nor the Conference of the Four, nor any other Conference whatsoever, can take under consideration the borders of my country, within which there is not a single inch of foreign land… Let the whole world know that the Albanian people do not allow their borders and land to be discussed… The Albanian people have not sent their delegation to Paris to give an account, but to demand accountability from those who harmed them so greatly and whom they fought fiercely until the end!’

And after this historic declaration, Enver Hoxha walked out of the Conference proceedings, returning to the Homeland, to his people – from whom, like Antaeus, he drew endless strength and courage.

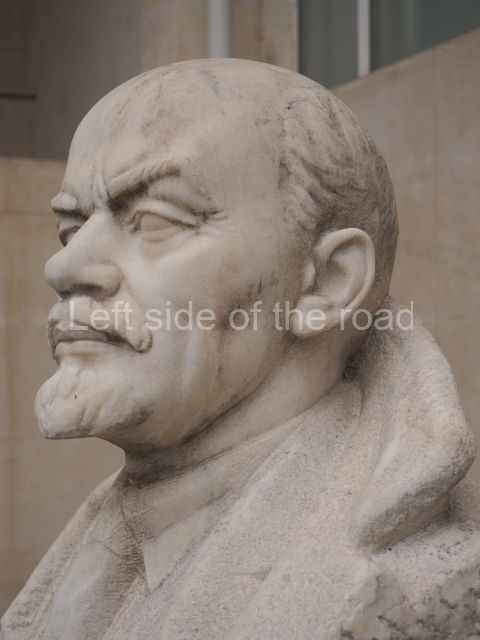

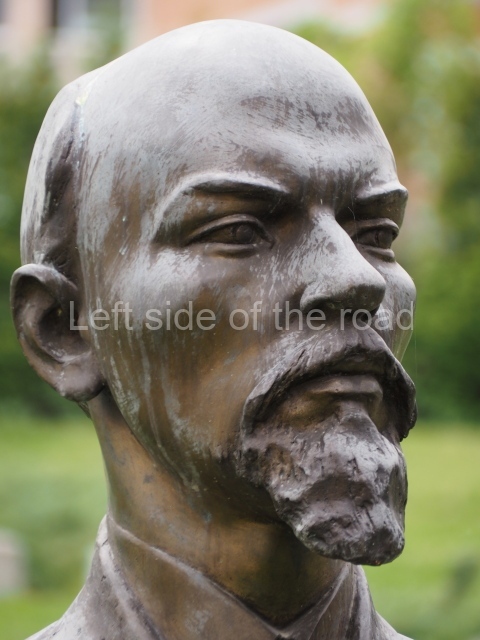

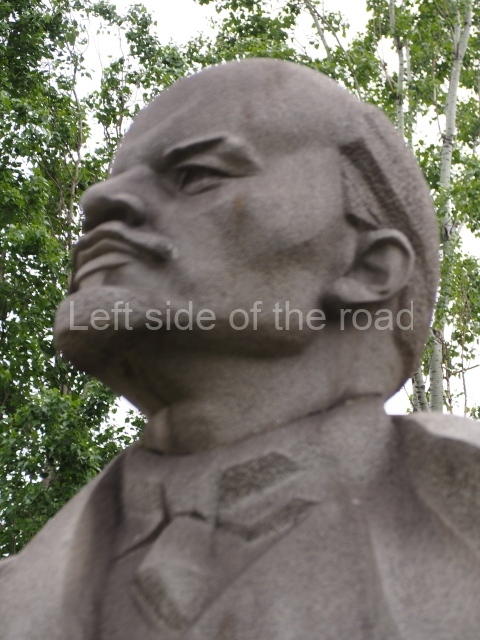

In November 1960, Enver Hoxha’s courage rose to legendary proportions. It was a moment of direct confrontation with a threat looming over the international communist movement and, at the same time, over socialist Albania. The clash was face-to-face with the leader of the vast state that made up one-sixth of the globe – the father of kukuruz (maize), Nikita Khrushchev. But this ‘Cyclops’ of the great Eurasian land, when confronted with Enver Hoxha in that bitter winter of the aged Kremlin, resembled the smallest copy of a Russian Matryoshka doll. The opposite was true for Enver Hoxha. His towering and expressive appearance matched perfectly the argument and truth he stood for, all accompanied by rare courage. This was because he came from Albania, where manhood is not measured by weight or position, but by resistance and bravery, by deeds and actions for the benefit of the nation. At the end of that fierce confrontation with Nikita Khrushchev, Enver Hoxha, with a loud and confident voice, would declare: ‘I defend the interests of my country!’

That phrase – delivered with Albanian fire and manliness, in front of Moscow’s treacherous leadership – needs no commentary. As history proved, the entire philosophy of Enver Hoxha’s life and work is encapsulated in that phrase: ‘I defend the interests of my country!’

For half a century, this ‘Man of the Land’ – like no one else in the old or modern history of the Albanians – defended and elevated Albania’s and his nation’s interests to the highest levels.

* * *

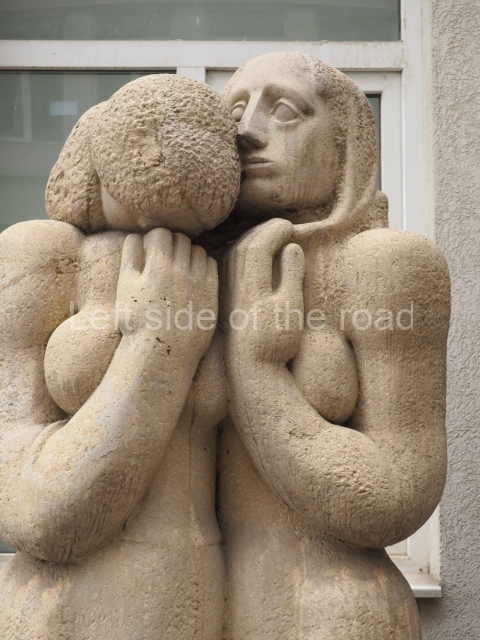

It cannot be said with certainty whether an era produces colossi, or whether colossi create an era. But in our case, we can declare without hesitation: Enver Hoxha created an era for Albania and the Albanian nation. An era that placed Albania on the map of the world, raising the Albanians and their country to the highest level of dignity as a nation!

The apologists of the bourgeoisie accuse us, the communists, of the ‘cult of personality’! But who created and continues to fuel the so-called ‘cult of personality’ for the leaders of the proletariat? It was – and still is – the dwarfs of history, starting from the bald Khrushchev to the confused, bearded, scarf-wrapped types of today, who, unable to climb the Great Mountain, spit at it from below – even though their spit only falls back on their own faces!

All the high epithets in the world would not be enough for Enver Hoxha, even if all the dictionaries of the world’s languages were combined. For nature has rarely crafted such a complete person – in stature and presence, in intellect and heart, in courage and bravery, in self-sacrifice and devotion, and above all in a monumental work for the benefit of his nation – as it did in Enver Hoxha.

The ‘cult of personality’? How laughable – and equally deceitful! For a priest said to have cured one or two blind people (surely with remedies unknown in ancient times), the Church and its propaganda perform canonization, and then raise a cult around him where thousands of believers pray. But for Enver Hoxha – who performed real, not imagined, miracles; who shifted history and created an era; who cured not one or two individuals of blindness, but three million Albanians; whose theoretical and practical work lifts not just two or three crippled men, but thousands and millions of proletarians across the world – we supposedly have no right to honour him with a cult?

Yes! Enver Hoxha fully deserves the cult. He is – and will remain – the cult of honourable Albanians. He is – and will remain – the cult of the members of the Communist Party and their supporters, because his majestic figure represents the true national ideals.

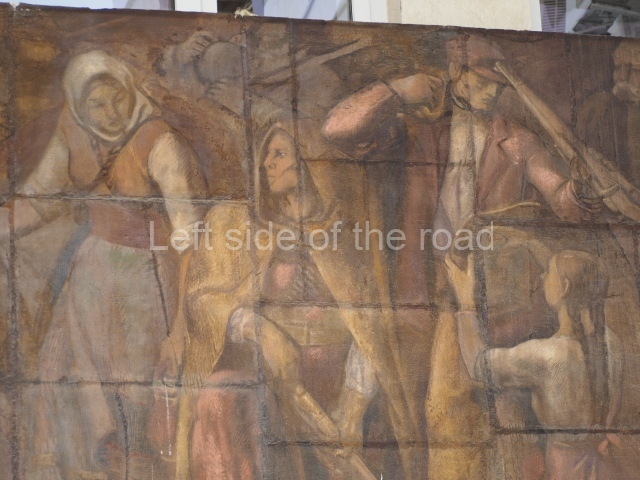

Our Albania today, as I wrote at the beginning of this piece, is without a Master of the House. A full 40 years without a master. And how can a house be without ‘its Master’? ‘See and write,’ says the people – and what is to be written is clear for all to see. In the absence of the ‘Master of the Hearth,’ the pack of wolves, along with the great she-wolf of capitalism, has overrun Albania and is tearing it apart without mercy – just as hyenas do in the dark!

On the eve of the March 22, 1992 elections – elections that marked the rise to power of the old bourgeoisie and its new offspring – the chairman of the Communist Party, the revolutionary poet Hysni Milloshi, made a call: ‘Albanian people, do not blindfold yourselves with a black cloth before the ballot box, because afterwards not even the cuckoo will be able to lament your fate!’ But the Albanian people, unfortunately, under the pressure of the horns and drums of ‘bourgeois democracy,’ did not heed the call of the chief communist of the time. With two fingers raised and their minds lowered, they cast their votes into the black bourgeois box – a box that for the past three and a half decades has darkened, and continues to darken, their lives in every aspect.

The Albanians must now remove this black cloth from their eyes. Three and a half decades are enough to understand that bourgeois democracy can bring nothing but the darkness into which the people have completely sunk. Until when will this continue? Has hope been lost for emerging into the light once again?

No! The Albanians will once again find the Master of the House – without whom the country, just like a family, cannot stand firm or move forward. It cannot be otherwise. History repeats itself. And in today’s world, this ‘repetition’ has a much shorter time span than in the past. Albania will soon give birth to the ‘Man’ who will lead it out of the tunnel of darkness – towards the true light!

(Translated by November Eighth Publishing House (Canada) from the Albanian original)

See also;

Enver Hoxha – Speeches and articles

Enver Hoxha – Memoirs, Diary Selections and Compilations of Articles