Labna

Labna – Yucatan

Location

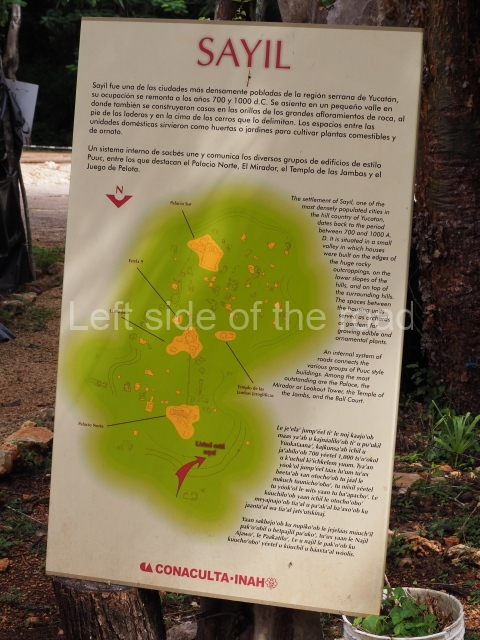

The Labna ruins are situated in the Bolonchen district, 9 km east of Sayil and 3 km from Xlapak. The studies conducted in this archaeological area suggest that the area around the centre of the pre-Hispanic settlement occupied just over 1 sq km with an estimated population of 2,000. A suburban area of an additional 25 ha is also known, situated on the hills that define the south-west corner of the urban area, where there is a small group of masonry constructions inhabited by people of a relatively high social standing. Labna is one of the most important examples of a class of settlements which are distinguished by their relatively common dimensions and populations and which represent the majority of the Maya people who lived and prospered in the Puuc region during the two centuries that the Terminal Classic is estimated to have lasted (AD 750-950) in the Yucatan Peninsula.

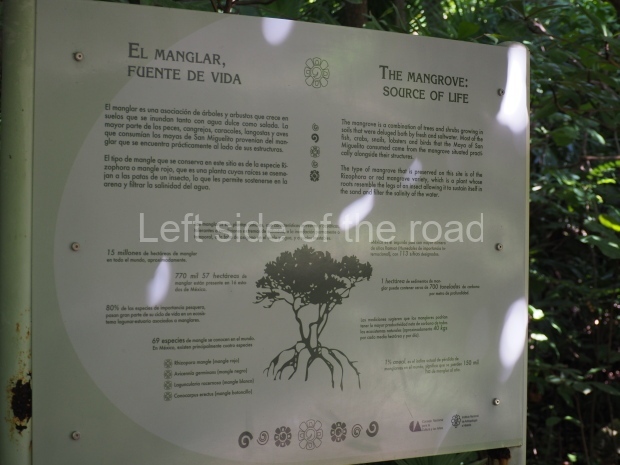

According to experts such as Pollock, Edward Kurjack and Nicholas Dunning, the layout of the main architectural precinct at the site and the types of structures it comprises are typical of many archaeological sites in the region. However, Labna is regarded as the most characteristic Puuc site and is well worth a visit for those interested in gaining a more complete picture of the social organisation of the population who lived in this undulating landscape, of the types of buildings they constructed to accommodate the community and of the principal spaces they created for conducting their civic and religious activities. Like many other mountain sites, it was first recorded by the American traveller John Stephens and the British artist Frederick Catherwood in the late 1830s. However, the first archaeological explorations took place some 50 years later, led by the American consul in Yucatan, Edward H. Thompson, an archaeologist affiliated to the Peabody Museum at the University of Harvard. His excavations were the first ever conducted in the Maya area by a researcher linked to this institution, which to this day continues to promote the studies of numerous distinguished Mayanists. Although many of his activities were controversial, Thompson authored a study on the chultunes at Labna, the first ever publication devoted to the numerous cisterns designed to collect and store rainwater. These bottle shaped tanks tend to be situated in the courtyards of residential units, which served as collecting areas; the same purpose was served by the roofs of the constructions around the courtyard, which descended steeply towards the mouth of the cistern. This was reduced in width by a stone ring-shaped parapet, on which sat a round slab stone that acted as a movable lid. This minimised the loss of water through the process of evotranspiration and may well have also reduced the entry of rubbish as the parapet was several centimetres higher than the surrounding collecting area. Many cisterns were excavated with a long neck to cross the bedrock and reach the relatively soft sascab or limy layer in the process of petrification. In addition to offering an example of the Maya’s ingenuity in adapting to the extreme conditions of their environment, the chultunes also played a vital role in guaranteeing the survival of the inhabitants all year round by providing water, a precious commodity, during the dry months.

Pre-Hispanic history

The excavations undertaken by archaeologists from the Yucatan INAH Centre have revealed the existence of constructions and materials that confirm that the first settlers occupied Labna from as early as the late Middle Preclassic (c. 500 BC). However, the presence of buildings with Early Puuc architecture, such as the Colonnette and Mosaic styles, associated with Cehpech slate ceramic vessels, indicates that the site was primarily occupied during the Terminal Classic (AD 700-900), when Labna experienced its greatest splendour. Thereafter, the population declined considerably. There are also remains of various later constructions, regarded as transitional buildings between the Terminal Classic and the Early Postclassic (AD 1000-1100), but otherwise everything seems to suggest that the site had been totally abandoned by the end of the Early Postclassic (AD 1200).

Site description

The architectural groups inside the area open to visitors are the Arch Group, the North Square, the Mirador Group, the Temple of the Columns and the Palace. The first three belong to the same architectural complex and are connected to the Palace by a sacbe or internal causeway.

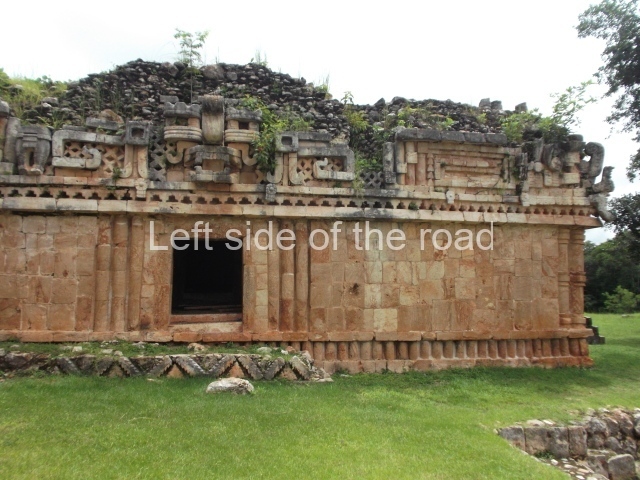

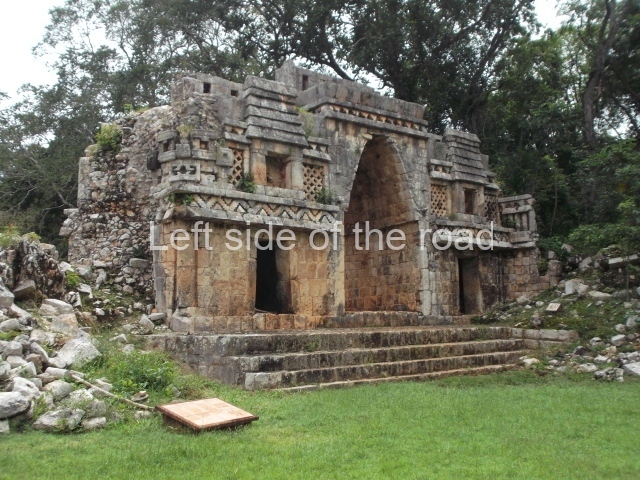

Arch group.

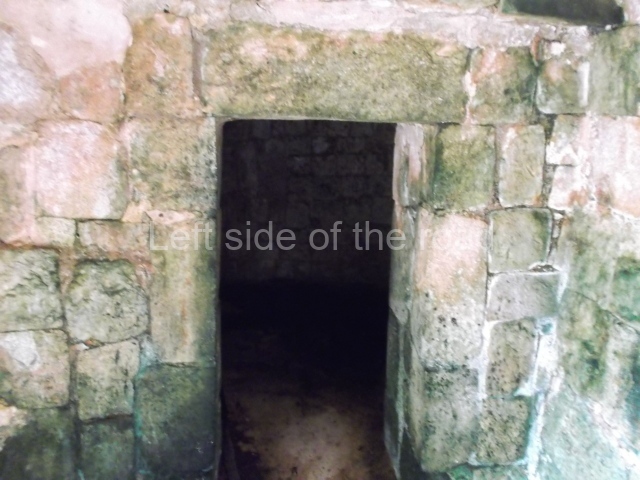

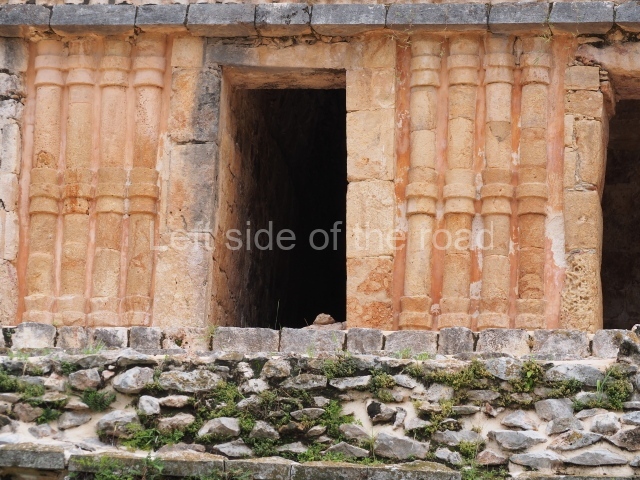

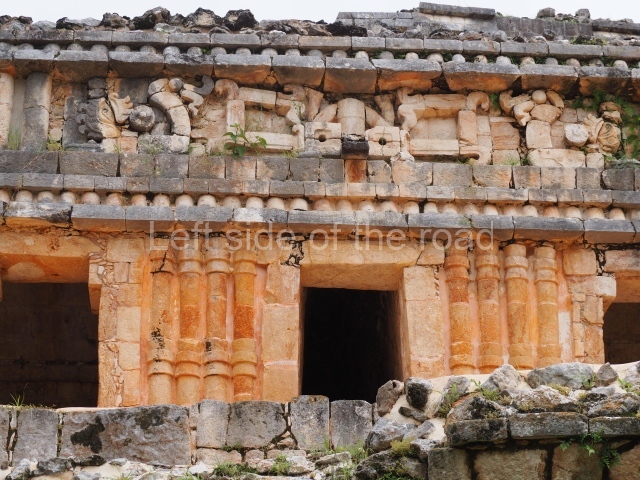

This comprises several adjacent structures, the most outstanding of which in terms of its state of repair and architectural merits is the Arch or vaulted doorway connecting the group to the North Square and the causeway. When Stephens and Catherwood visited Labna over 170 years ago, part of the structure adjoining the Arch was still standing, forming the south wing of the group. This construction survived upright until the first half of the 20th century, and we therefore know that it was a palatial building, with a double bay in the central section and a frieze decorated with tiny columns in the Puuc Colonnette style. Although now in ruins, the buildings on the west and north sides probably date from the same period, including Structure 13, which forms the north-west side of the group, and Structure 12, a circular platform with a monolithic altar which must have originally stood at the centre. The Arch displays several details that suggest it was a late construction, abutted to its neighbours several decades afterwards. Its interior decoration or north-west facade consists of a columnar corner, a mask at the north corner, panels of latticework with two niches where it is still possible to see fragments of stucco-modelled quetzal feathers with traces of green, blue and red pigmentation. The feathers formed part of the headdress of different figures seated in a cross-legged position, of which the only remaining element is the butt which must have anchored them to internal wall of the niche. Above the niches are miniature representations of Maya huts. Visible on the roof are three sections – the highest one in the middle – of a roof comb. This composition bears a great similarity to that of the interior face of the arch leading to the Nunnery Quadrangle at Uxmal. The other side of the Arch displays a frieze with geometric decoration in the form of the stepped frets commonly found in the Maya area and made in the Puuc Mosaic style, which reinforces the theory that the vaulted doorway at Labna is a late construction.

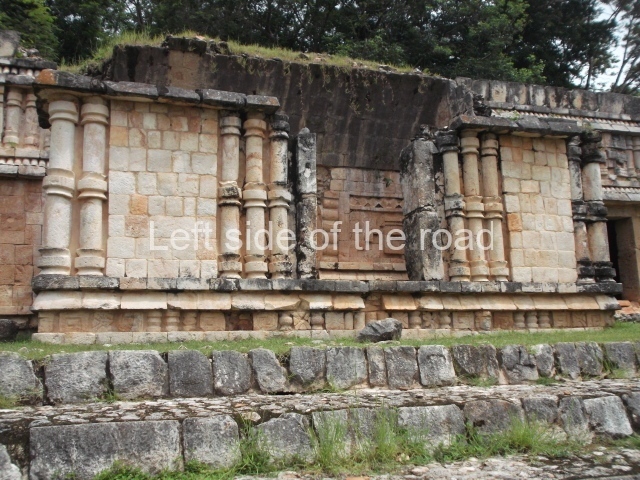

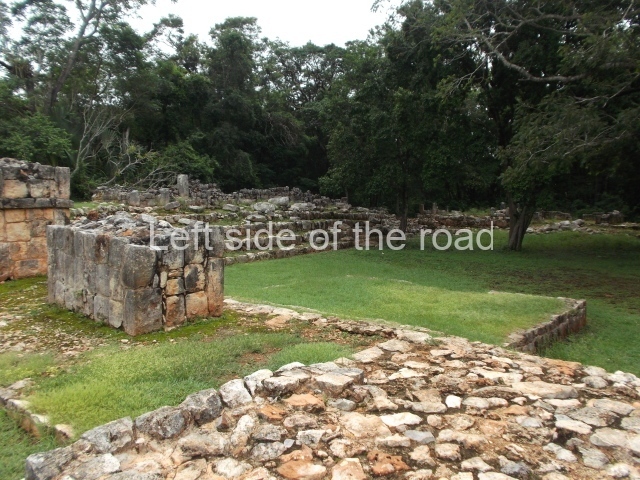

North Square.

This is composed of the north wing or Structure 8, Structure 7 which seals the east side, Structure 9 on the south side, Structure 10 (a small pyramid that has not been restored) and the Arch that defines its west side. The sacbe or raised causeway links this space to the Palace. On reaching the north wing it adopts the form of a ramp leading to the interior of the square. The east side of the ramp is occupied by the remains of two solid constructions which according to the explorations conducted by the INAH between 1993 and 1997 formed two free-standing towers, similar in shape to the towers at Nocuchich and Chanchen. They once stood over 7 m high and had a stucco decoration affixed to the tower by means of butts embedded in the masonry, like the decorative figures on the Mirador’s roof comb. The remaining structures are open at the front and preceded by columns. The elongated structure that forms the east wing was simply decorated with ‘broken mouldings’ above the entrances, while the structures on the south-east side had friezes decorated with stucco anthropomorphic motifs. Both these constructions and the one that seals the east side had slab stone roofs, which indicates that they are the oldest buildings at the site. The shape and the absence of domestic utensils suggest that this space was used for civic and religious functions and was probably the principal ceremonial precinct at Labna as early as the beginning of the Late Classic. A ramp at the centre of the south wing provided access to the South Square, where there are more early structures preceded by columns; these have not yet been restored but they must originally have formed a single plaza with the North Square.

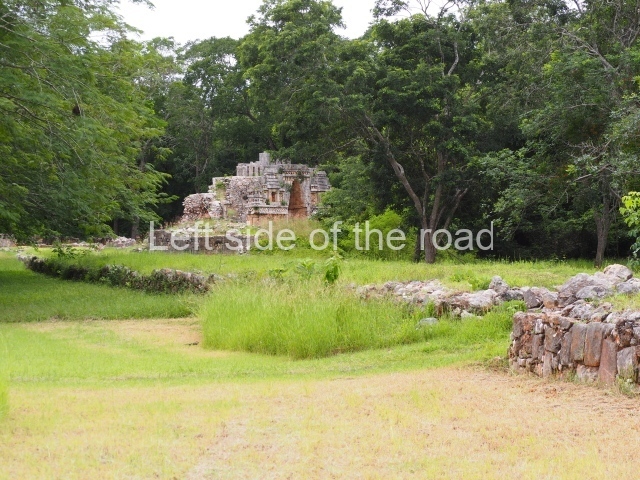

Mirador Group.

The Mirador is a stepped pyramid and the highest construction in the core area of Labna. Only the western section of the temple at the top of the pyramid has survived. It once had a stairway at the front, beneath which it is possible to see an exposed section of an earlier structure, which was completely covered when the stairway was built. Both the temple at the top of the pyramid and the substructure display the same Early Puuc architectural style, with simple rectangular-shaped medial moulding. The most interesting section of this construction is the roof comb or false facade on top of the roof, which still displays a fair number of butts that supported the stucco decoration and has retained its original height. Visible at the south-west corner of the building is half of a stucco bundle figure wearing a loincloth. There are also fragments of low and high reliefs, most of them anthropomorphic. This construction appears to have had a commemorative function, serving as a type of ‘billboard’ for announcing important events related to the former governors of Labna. Much of the building and its roof comb were still standing when Stephens and Catherwood visited Labna. Thompson also describes two human figures with a ball between them, as well as a large seated figure above the central door, which have now disappeared. The surveys conducted by the INAH’s Labna Project indicated that there is no ball court at this site, which means that the scene with the ball must be a reference to an event at a neighbouring site such as Sayil, where there is evidence of this type of construction. Opposite the Mirador, in the courtyard, is a circular construction and at its centre an altar in the form of a truncated cone. This monolith displays the remains of five anthropomorphic figures carved beneath an upper band of cartouches with hieroglyphic writing which it has not been possible to decipher. This group was accessed from the south side, where the remains of a ramp have been excavated and restored.

Sacbe.

This linear construction connects the Palace, a multi-purpose building, to the North Square and the Arch and Mirador groups, the two monumental precincts that formed the core area of the ancient city of Labna. The excavations conducted prior to its restoration indicated the presence of an earlier causeway, partly dismantled and buried when the new sacbe was built. During its first phase, the causeway led to the Central Wing of the Palace but was subsequently diverted towards the south-west corner of the East Wing of the Palace. The sections still visible today indicate that it was originally lower and a little narrower, and that its retaining walls were made of finely cut stones rather than the coarse ones of its final stage. The south side reached the North Square via a double ramp, whose exterior face (of the north side) was levelled during the final construction phase. During the dry season it is possible to see part of the east side of the ramp, in a hollow next to the remains of the east tower left for this purpose by the archaeologists.

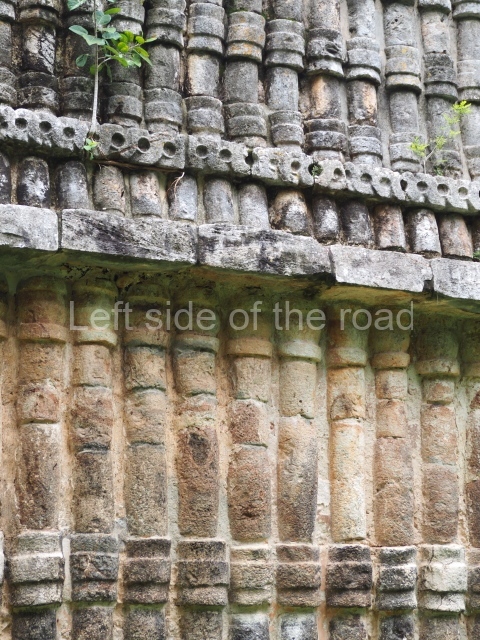

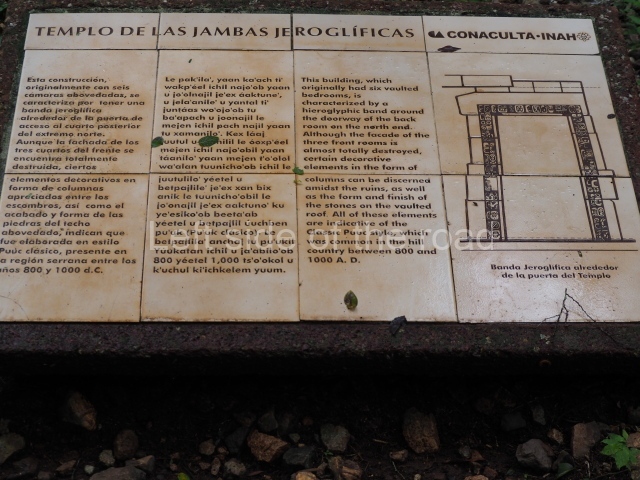

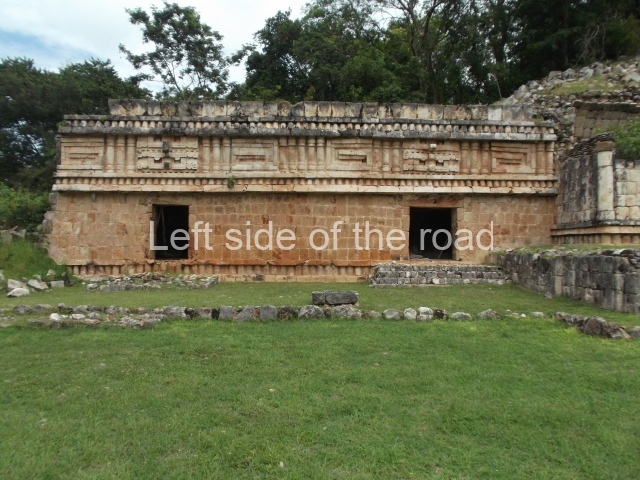

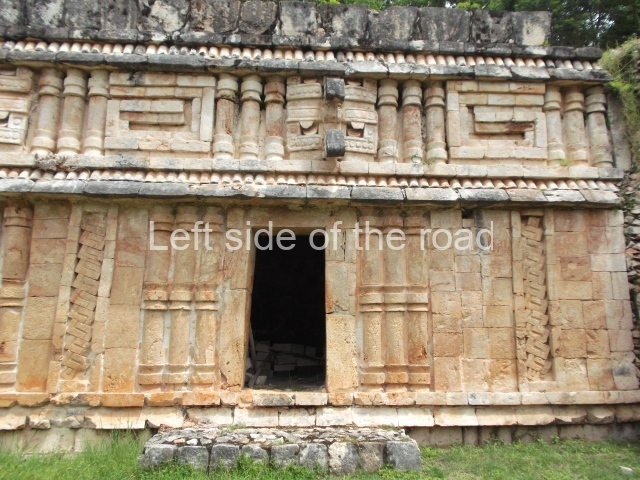

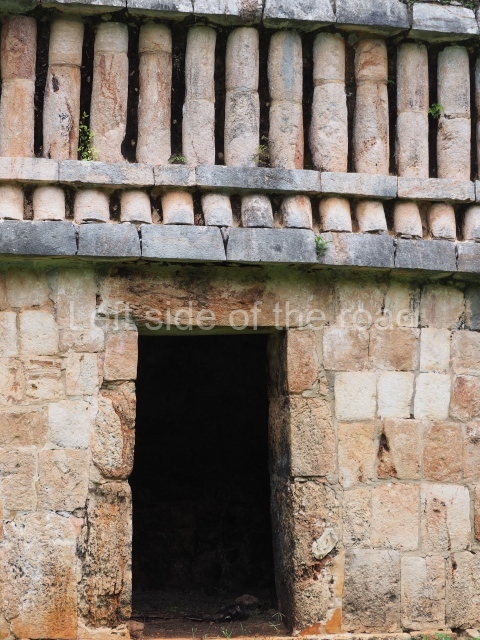

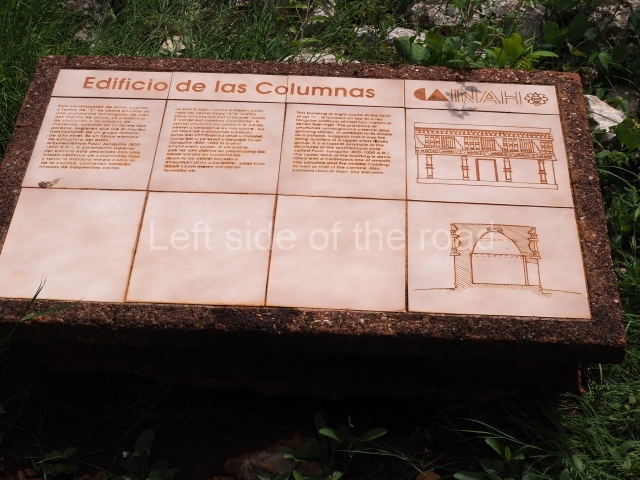

Temple of Columns.

This six-room building situated east of the Palace occupies a rectangular platform approximately 1.5 m high, which has not been restored. The access was on the west side, where there must have been a stairway. Both the front and back display a continuous decoration of tiny columns in the characteristic Puuc Colonnette style. The presence of an underground cistern at the front and service platforms probably used for preparing food at the front and back, both with additional cisterns, as well as its proximity to the Palace, indicate that it must have been the dwelling of a high-ranking family during the Late Classic.

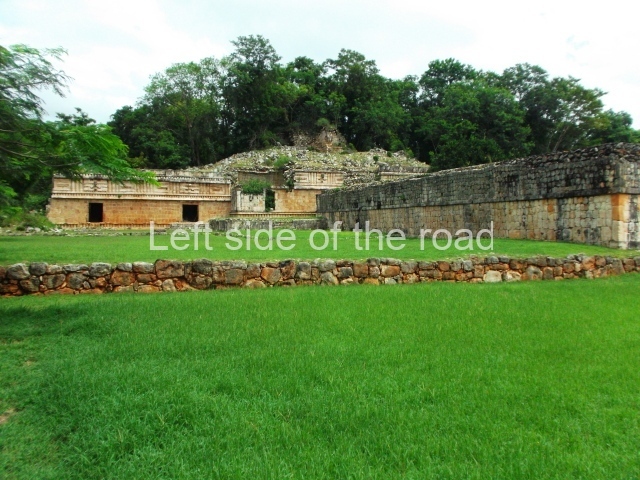

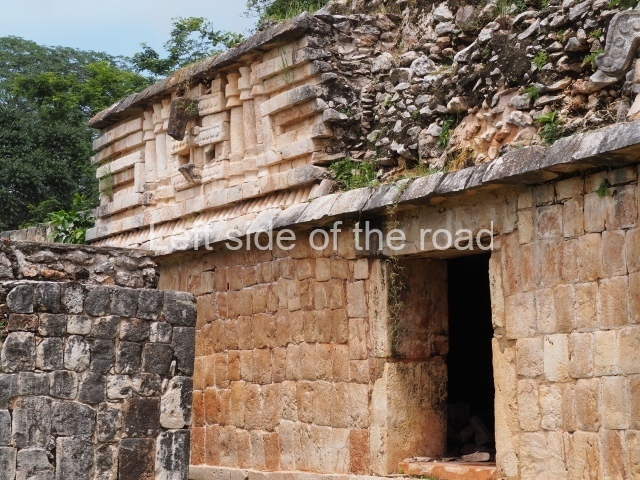

Palace.

This two-storey construction with 67 rooms is the most important building at the site. Although difficult to believe, several buildings on the top level pre-date the ones on the lower level. This is because the builders levelled and filled a natural hill, using several buildings on the lower level as retaining elements to increase the space at the front of the top level, including the roofs of the buildings. This ingenious building method was used in numerous other multistorey constructions in the Puuc region, filling and levelling to create large terraces on the slopes of karst hills and erect imposing buildings with less effort than if they were constructed on a totally flat surface. The area open to visitors is the lower level, which is composed of the west, central and east wings. Although the structure has yet to be explored in its entirety, the evidence uncovered suggests that it must have had a residential function; even so, the front buildings may have been used for another purpose. Situated in the West Wing are the only building foundations that did not have a corbel vault roof. Similarly, a large quantity of grinding stones and their respective quern stones were found nearby. At the rear of the structure, on the natural surface next to the platform, several caches of broken cooking pots were found. All of this suggests that this must have been the Palace’s service area, where food such as different types of tamales, atoles and tortillas were prepared for the occupants. The Central Wing contains the most elaborately decorated buildings. The excavations indicated that the west building pre-dates the central one, which in turn pre-dates the building on the east side. The west building was constructed in the Early Puuc style, while the north and east buildings correspond to the Puuc Mosaic, a much later style, which means that the time difference between these two must have been much shorter than between them and the west building. The sides of the central building display panels formed by interwoven mats, a symbol clearly associated with the nobility in the Maya area. Other interesting details are the heads carved in the lower moulding and the fact that the interior wall of the room is decorated as if it were an exterior wall and has benches flanking the entrance to the inner room. The decoration of the East Wing is much more elaborate, complex and illuminating. The central motif is a giant long-nosed mask originally flanked by anthropomorphic sculptures; the front of the nose is inscribed with a hieroglyphic date of the tun ahau type, corresponding to the year AD 862. In the southwest corner is a mask with complex symbolism. Although shaped like a reptile, it also has fins, feathers and the open jaws of a lizard revealing a human head inside. On the lower moulding of this corner is a sculpted head. These details, combined with the shape of the building and the dedication date, suggest a ceremony related to the accession to the throne of one of the last rulers of Labna. There are signs that the Palace was undergoing expansion when for some reason the site was abandoned. The north-east wing and sections of the upper level were never completed. There is evidence of unfinished building work at many sites in the mountain region.

Tomas Gallareta

From: ‘The Maya: an architectural and landscape guide’, produced jointly by the Junta de Andulacia and the Universidad Autonoma de Mexico, 2010, pp 367-371.

Labna

1. Arch; 2. North Square; 3. South Square; 4. Mirador; 5. Sacbe; 6. Temple of the Columns; 7. Palace.

How to get there;

Not easy if you don’t have your own transport. There are no buses or colectivos that run along this road. Although the three sites (Labna, Xlapak and Sayil) are all within a 15km stretch of the road unless you hire a taxi from Santa Elena (expensive) you have to depend upon your wits, imagination and good luck.

GPS:

20d 10′ 26″ N

89d 34′ 46″ W

Entrance;

M$70