Victorious Fatherland Liberation War Museum – Panorama

More on the DPRK

Victorious Fatherland Liberation War Museum – Pyongyang

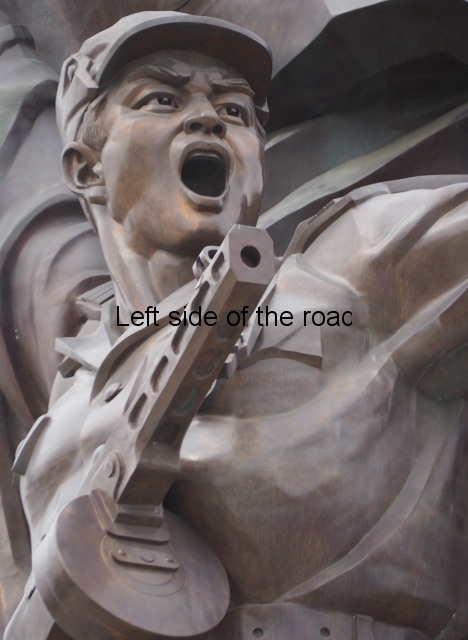

The complex that is the Victorious Fatherland Liberation War Museum contains one of the largest collections of Socialist Realist art in Pyongyang, the Democratic People’s Republic of Korea (DPRK). Comprising of ten slightly more than life-size tableau, stand alone statues, bas reliefs and mosaics these amazing works of art tell the story of how the people in the north of Korean peninsula stood up against the invading forces of the United Nations – puppets of United States imperialism – during the just over three years (25th June, 1950 – 27th July, 1953) of what the west calls ‘The Korean War’ but which the people of the north call the ‘Victorious Fatherland Liberation War’.

(The other large concentration of Socialist Realist Sculptures are at the Mansudae Grand Monument where the two huge statues of Kim Il Sung and Kim Jong Il are flanked by two tableau, comprising 228 bronze figures which depict, on the left, the War of Liberation and, on the right, the Construction of Socialism. This is considered the most sacred site in the DPRK and photographing, in detail, the tableau is not really possible.)

From the introduction to the book ‘Victorious Fatherland Liberation War Museum’ (Foreign Languages Publishing House, DPRK, 2014):

The Victorious Fatherland Liberation War Museum is located on the bank of the picturesque Pothong River in Pyongyang, the capital of the DPRK.

Under the auspices and energetic guidance of Marshal Kim Jong Un, the museum was renovated in July Juche 102 (2013) on the occasion of the 60th anniversary of the victory in the war in order to hand down to posterity the brilliant tradition of invincibility and immortal patriotic exploits performed by Generalissimos Kim Il Sung and Kim Jong Il and the indomitable fighting spirit and heroic feats displayed by the DPRK service personnel and people in the struggle for national defence.

Covering an area of 93,000 m², it comprehends the protracted history of the Korean people’s struggle, ranging from the periods of the anti-Japanese revolutionary struggle and the Fatherland Liberation War to the anti-imperialist, anti-US showdown in postwar years. On display there are over 300 revolutionary relics, 120,000 war relics, materials and data in their original state.

With a total floor space of 51,000 m² its main building consists of three storeys above and one storey under the ground.

In the central hall stands the colour statue of Generalissimo on Kim 11 Sung who is acknowledging enthusiastic cheers of the Korean service personnel and people in the plaza of war victory in July 1953.

On the first floor are a hall displaying the materials relating to the anti-Japanese revolutionary struggle which was organized and led by Kim Il Sung, especially those relating to main operations and battles fought in those days, a hall displaying the materials about the building of regular armed forces for the first time in Korea after its liberation, and a hall displaying material evidence that the US imperialists who had occupied southern half of Korea committed, in collusion with the south Korean puppet army, armed provocations against the north and at last unleashed the Korean war.

On show on the second floor are the materials relating with the strategic policies for every period and stage of the Fatherland Liberation War advanced by Supreme Commander Kim Il Sung, brilliant military strategist and iron-willed commander, main battles and heroic struggle of soldiers and civilians who defended every inch of their country at the cost of their lives to carry out the orders of the Supreme Commander and other relics.

On the same floor are also halls dedicated to the Chinese People’s Volunteers who participated in the war upholding the slogan “Resist America, aid Korea, safeguard the home and defend the motherland,” to the peoples over the world who rendered selfless material aid and moral support to the Korean people, to the materials about brutal atrocities committed by the US forces during the war and their bitter defeat, and to the brilliant victory won by the soldiers and people in the hard-fought war for national defence. On this floor are the halls of peculiar style dedicated to the anti-Japanese revolutionary fighters, leading commanding officers of the Korean People’s Army during the Fatherland Liberation War and internationalist fighters.

On the corridor linking the main building with the hall dedicated to the battle for liberating Taejon are exhibited the photos showing war heroes’ feats that would go down in national history and their relics.

On the third floor are the halls displaying the materials relating with Party political work Kim Il Sung conducted energetically to enlist all the soldiers and people in the effort to achieve victory in the war and those showing the struggle of the officers and men of services, arms and corps and the brave activities of the people in the rear.

In the hall dedicated to the Liberation of Taejon there is a large-scale panorama showing the victorious battle, which was recorded as a “living example of modern encirclement battle,” fought in line with the original tactics and under the adroit command of Supreme Commander Kim Il Sung.

The museum has also a hall that comprehensively shows the immortal exploits of Generalissimo Kim Jong Il who adorned the history of anti-imperialist, anti-US showdown with victory on the strength of Songun-based revolutionary leadership.

On show outside the museum are the merited weapons in the war, enemy military hardware captured during and after the war, and the Pueblo, a US armed spy ship which was captured in 1968 while committing espionage acts in the territorial waters of the DPRK.

The museum, built in a characteristic way in conformity with the architectural and aesthetic demands of the new century, will remain a structure representing the unshakeable faith and will of the Korean service personnel and people who are determined to defend the exploits of victory performed by the Generalissimos and carry them forward through generations under the wise leadership of Marshal Kim Jong Un, and a symbol of eternal victory of Songun Korea with great traditions.

The uniqueness of Korean Socialist Realist sculptures

Those of you who have visited this site before will be aware of the respect I hold for the art that’s represented in the Albanian lapidars – and that respect remains undiminished. But (why is there always a but?) the examples you will see in the DPRK are different. They tell the same story – more or less – but the images (and this is in all the main sculptural fields – sculpture, bas reliefs and mosaics) seem, in a sense, to be more refined. There’s a, dare I say it, finesse to the images in Pyongyang and the rest of the country which is missing from those in Tirana and other parts of Albania.

I’ve discussed this difference between different Socialist countries and the ‘feel’ you get from observing those images which were produced during the period of the construction of Socialism. For example, although both fine sculptures in their own right there’s a marked difference in style between the two bronze statues of Comrade JV Stalin which now stand neglected behind the National Art Gallery in the centre of Tirana.

As I consider the matter more I believe it’s possibly a difference between European Socialist Realist Art and that produced in Asia. The art traditions of the far east were finer than those of the west even before the first Socialist Revolution in Russia in 1917. The fine prints that have been produced on all sorts of materials in Asia are reflected more in some of the examples of British realism of the early part of the 20th century rather than the work of the Soviet Union or the paintings inside the actual National Art Gallery in Tirana.

When it comes to sculptures I believe the Asian examples, of both the DPRK and Socialist China, have been able to capture emotions in a manner that was much more subtle than their European counter-parts. The finest example I know of in China is the series of clay statues which were produced in 1968 (during the Great Proletarian Cultural Revolution) depicting the suffering of pre-revolutionary peasants. This series of statues telling the story of how poor peasants had to make payments in kind to oppressive and exploitative landlords is called ‘Rent Collection Courtyard’ (with the interesting Introduction to photographic version) which were displayed in what used to be a landlord’s house in Szechuan Province.

(I don’t know the fate of this collection of 114 statues. They were reproduced and put on show in Beijing but the politics represented by this story of the peasantry doesn’t fit with the present capitalist regime in China. The post 1976 (the date from which all the revolutionary achievements of the People’s Republic of China began to be reversed) regime even has an impact upon the public art, witness the tableau outside of Chairman Mao’s Mausoleum in Beijing – impressive in many ways but lacks the passion of the likes of ‘Rent Collection Courtyard’. Their sense of aesthetics also doesn’t bode well – just have a look at what they used to celebrate the Anniversary of Chairman Mao‘s Declaration of the People’s Republic in October 2017.)

Tienanmen Square – October 2017

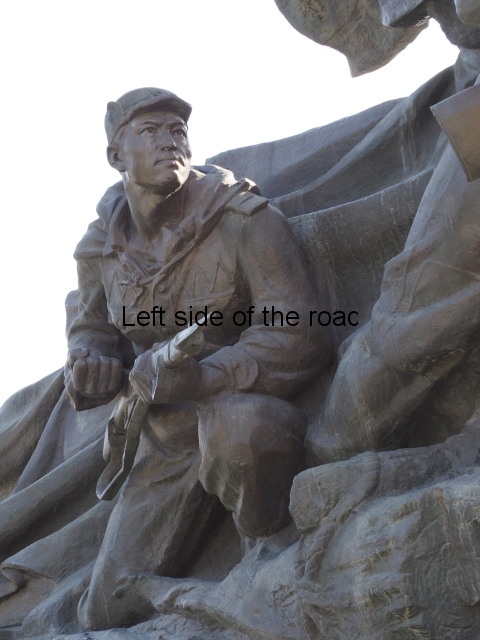

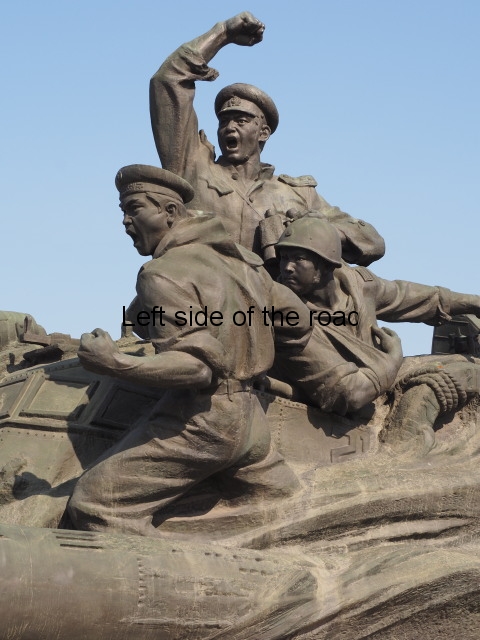

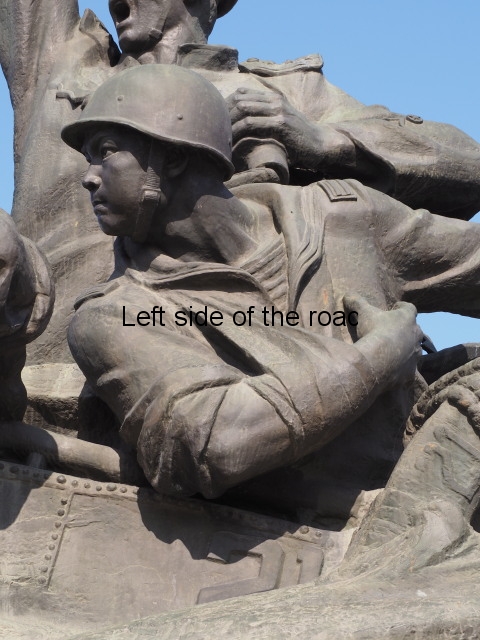

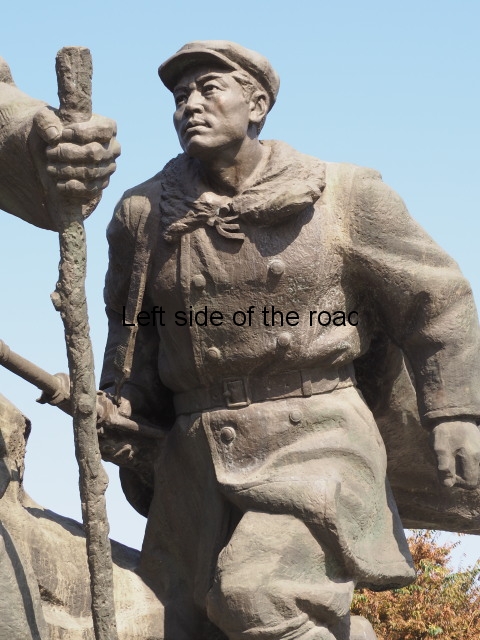

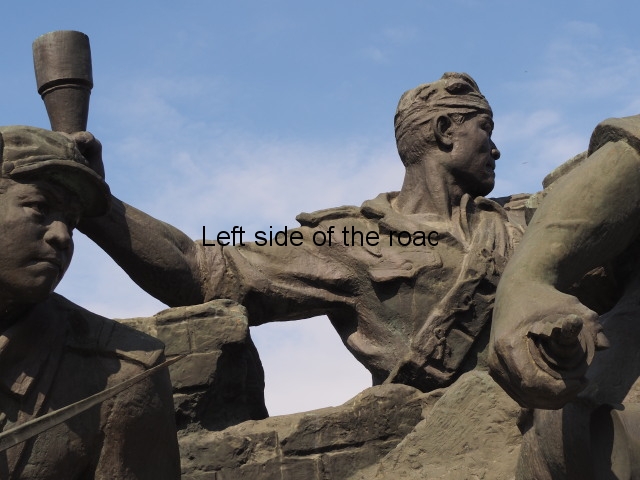

It’s revolutionary passion that determines the feeling and impression the viewer gets from the tableau at the Victorious Fatherland Liberation War Museum. The artists believed in what they were creating. Believed in the story they wanted to tell. Believed that it had a purpose over and above their own personal vanity. Yes, they should be proud of what they had created but their names will not be found on the results. They subsume their personal ego to the common good – which should be the aim of artists, as with all other workers, in a Socialist society. Celebrity status is an anathema to Socialism. All of these artists work out of the Mansudae Art Studio in Pyongyang.

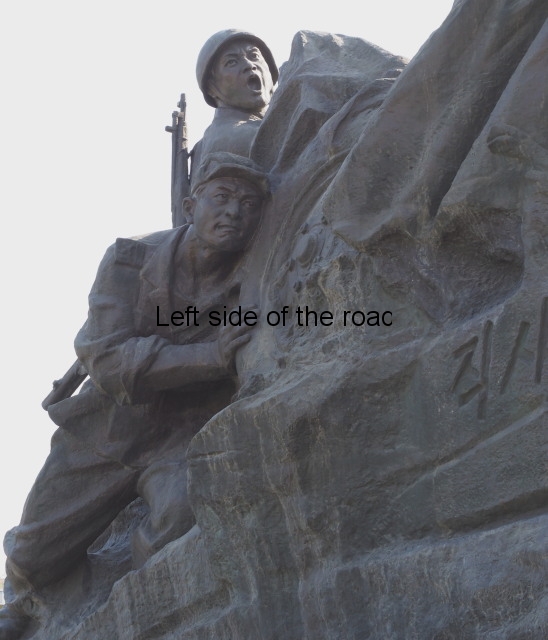

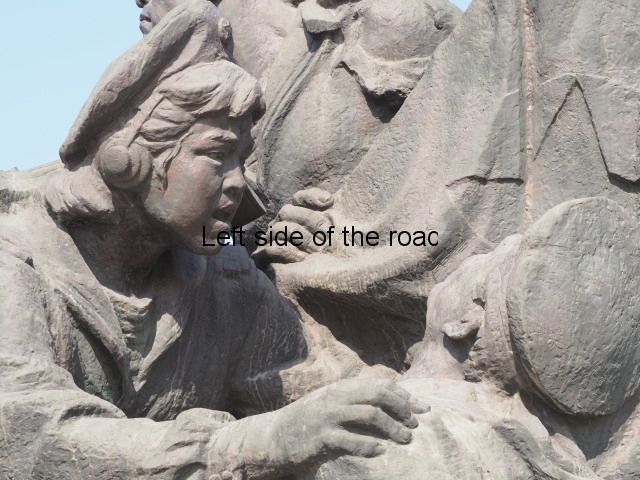

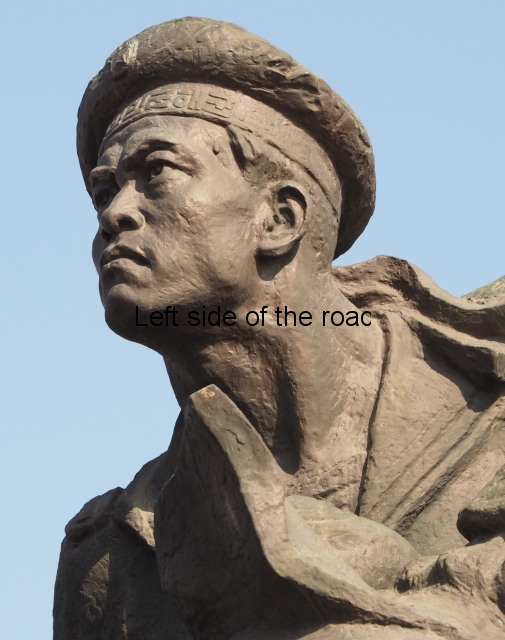

This finesse means that you get a much better impression of the emotions that the artists have wanted to create in their characters – anger, jubilation, compassion, determination, struggle, happiness and joy, etc.

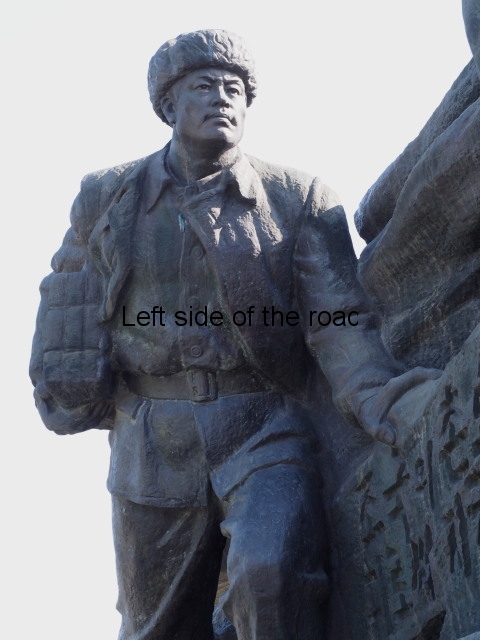

The sculptural aspects of the complex

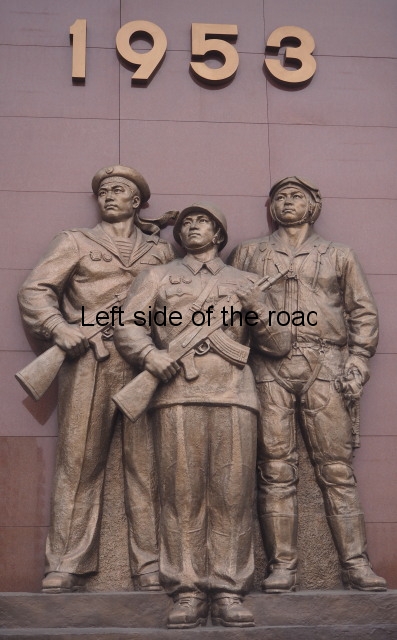

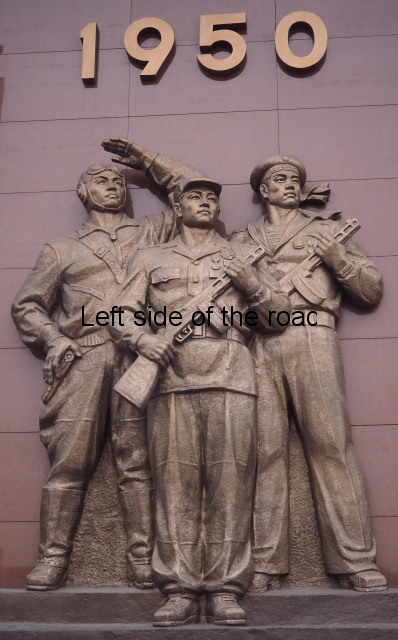

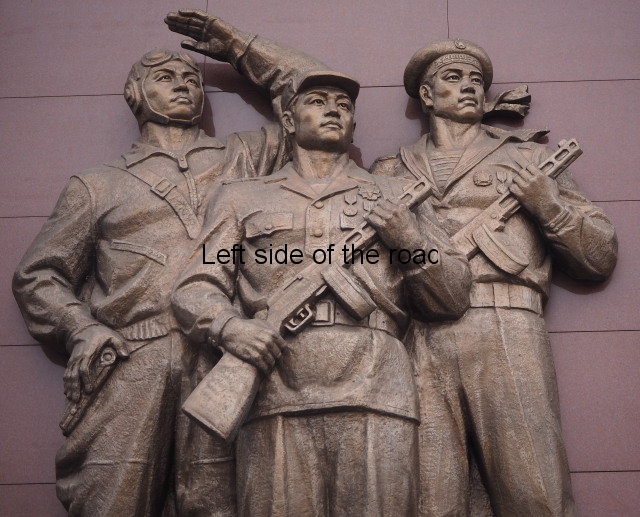

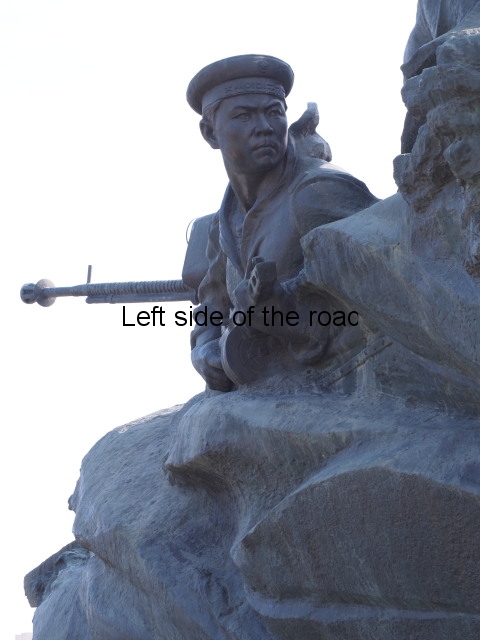

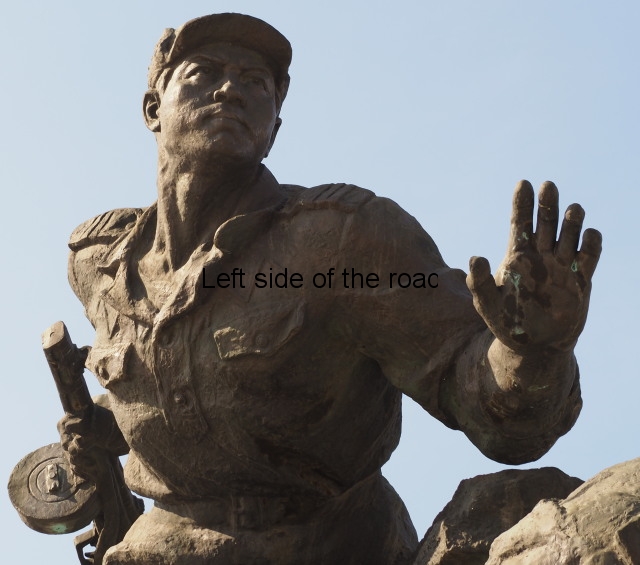

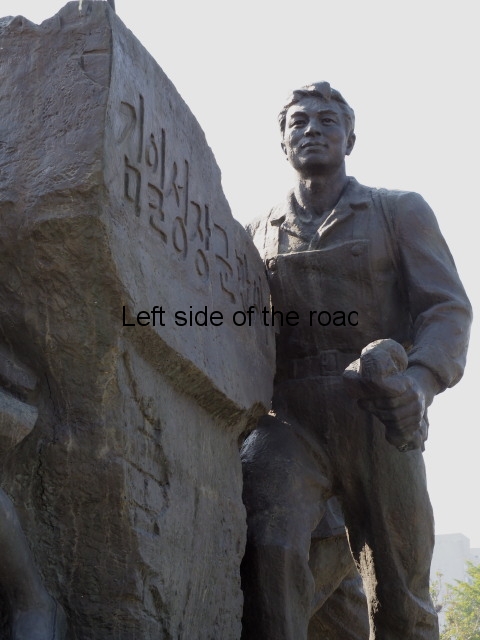

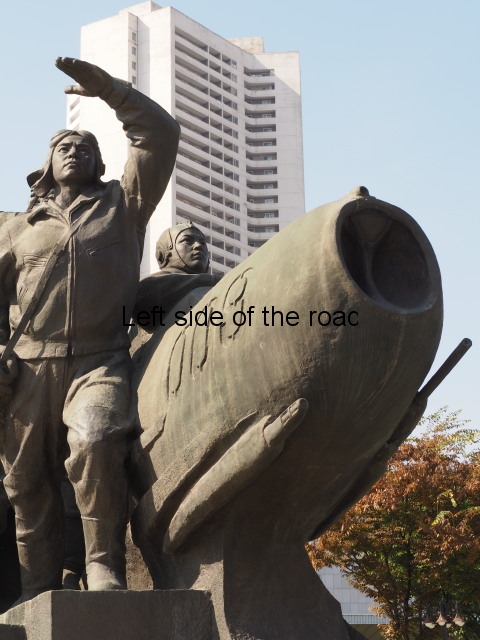

To enter the museum grounds you go through a triumphal arch. On the left side is a statue of three males representing the three military services – army, navy and air force. Above them is the number 1950, the year the War of Liberation started. They are dressed and armed with the weapons of that time. On the opposite side are three other males, of the same military services, but now everything has moved on a few years and their weapons and clothing have been updated.

1950-1953 – How things had changed

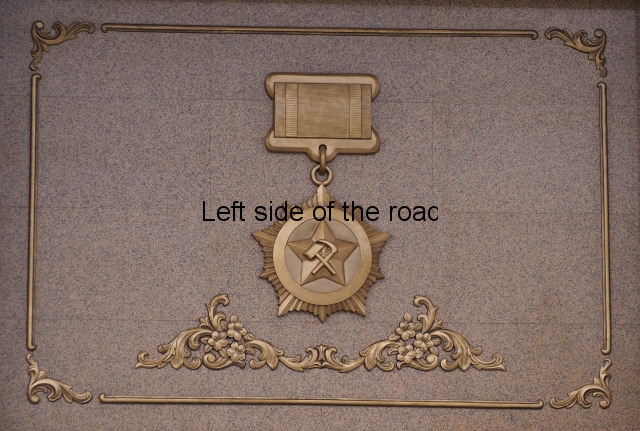

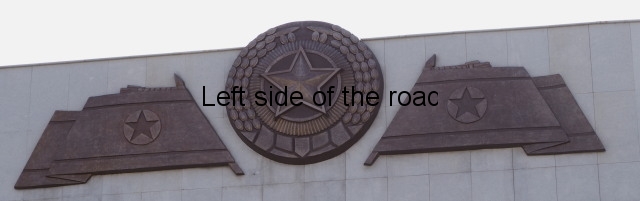

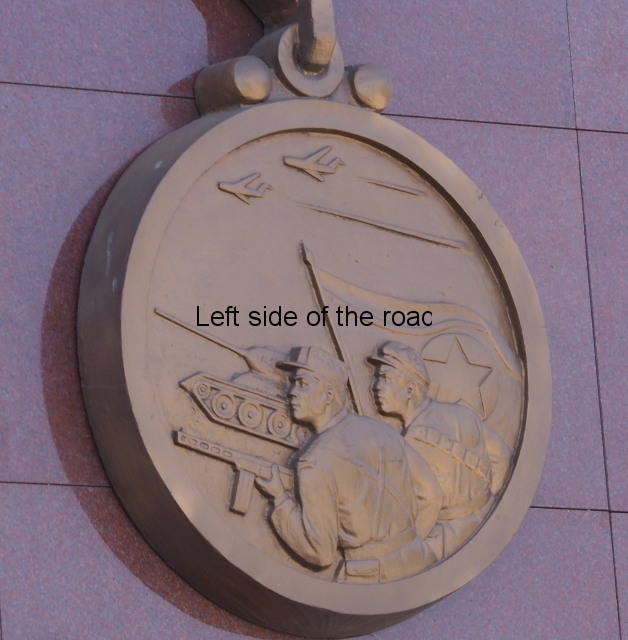

Above the vehicle entrance to the site, carved into the stone, are partially unfurled ceremonial banners, and in between the two sets of three banners is a campaign medal, the star in evidence.

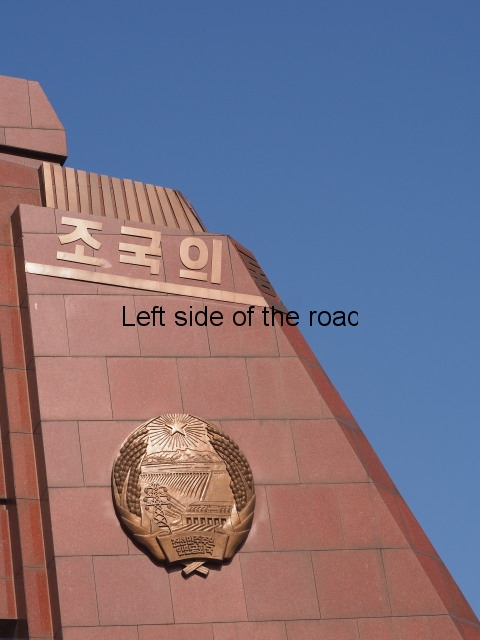

Going higher there’s a long, rectangular metal plaque with gold lettering where it is written in Korean (obviously) the words ‘Victorious Fatherland Liberation War Museum’.

On the highest point of the arch, in the middle, is a large, metal rondel with a large star in the centre. Flanking the star on either side is an almost semi-circle of ripe ears of rice. This follows the format established by the Soviet Union where the rice would have been replaced with ears of grain but in both cases stresses both the idea of providing the staple food as well as a reference to the importance of agriculture. On either side of this rondel is a DPRK National Flag, also of metal. This flag in reality is a red star inside a white rondel which sits on a red background. A blue strip, about a fifth of the width of the flag, is above and below the red portion. This design was adopted in 1948.

Once through the arch you enter a large, open esplanade. This, I assume, is where formal events take place at the location, especially anniversaries of the Liberation War, as this is the start of what is officially designated as the ‘Monument to the Victorious Fatherland Liberation War 1950-1953’. This was created in 1993 in time for the celebrations of the 40th Anniversary of the end of the war and extends from this esplanade to the single statue of the ‘Victory’ just before the entrance to the Museum building itself. This monument is dedicated to the Korean People’s Army and Korean People who defeated the US imperialists and its allies in the Fatherland Liberation War.

(I can understand why nations celebrate the end of wars but haven’t been able to get my head around the obsession that has gripped officialdom (and some of the population) in Britain over the start of the 1914 World War – the war that was supposed to end all war – and at every possible opportunity in the subsequent (almost) four years. I can only assume it’s part of a propaganda battle to keep the population numb with the idea of war and allows the country to threaten, and often take action, against other perceived enemies. There is only one year (1968) since the end of the Second World War in 1945 where British armed forces have not been involved in killing people in other parts of the world. On the other hand the DPRK has not invaded any country and they are branded as the aggressors. But then, why should we take facts into account?)

There’s a large, metal schematic of the complex, at the edge of the grassed area.

Schematic of the Museum Complex

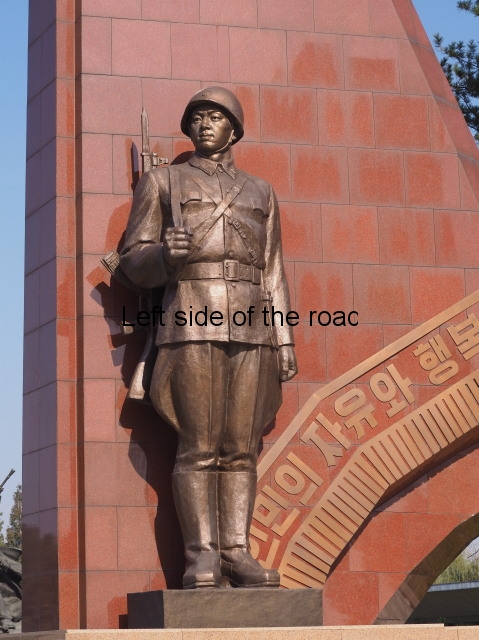

On either side of this plaque there are two Korean Soldiers – effectively on sentry duty to the monument. Standing to attention, with a rifle hanging from a strap over their right shoulders, they stand in front of huge stylised red flags, constructed of marble. They are looking slightly to their left, therefore covering the space between them. The soldier on the left stands underneath the symbol of the Korean Workers’ Party – the hammer, sickle and ink brush – and the soldier on the right stands beneath the emblem of the DPRK. At the top is a large red star, radiating light to all below. Beneath that is the outline of Mount Paektu, the highest mountain in the country and one which has had symbolic importance for centuries. Next is a schematic representation of a hydro-electric dam with a pylon taking the power to other parts of the country. Supporting these images, on both sides, are ripe ears of rice. Finally, in gold lettering on a symbolic red scroll is written the words ‘Democratic People’s Republic of Korea’.

From here on symmetry rules – as it does in many of the monuments in Pyongyang, both their construction and the relationship they might have with other structures in the city. One of the consequences of the blanket bombing of the North’s capital between 1950 and 1953 was that during reconstruction the architects were provided with a, more or less, blank canvas as there were virtually no buildings that survived intact in the city. That US bombing campaign saw more tons dropped on the north of Korea in those three years than were dropped by all combatant nations in the Second World War. That unenviable ‘record’ was broken when the US decided that it had the right to determine the future of yet another Asian people, when they interfered and invaded Vietnam in the 1960s.

Down the centre is an immaculately manicured lawn with seasonal flowers in the beds. There are also a couple of large and ornate fountains which are connected by a tunnel of water when operating. This whole area looks impressive at night (see the front of the booklet on the museum, link below) but, unfortunately a night time visit wasn’t on the cards when I was in the country.

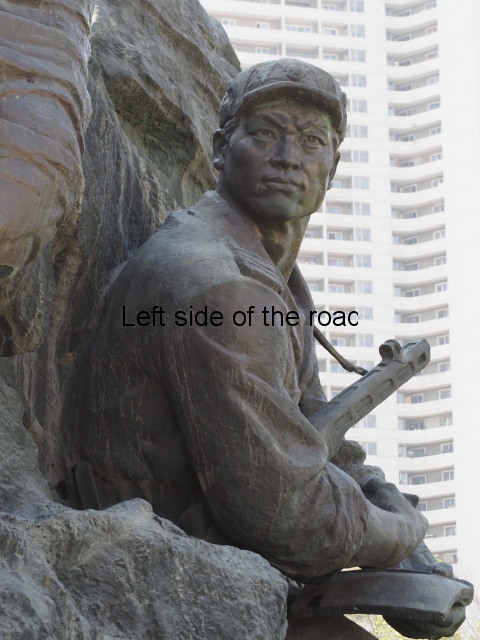

However, for me, the main interest is the collection of ten, large tableau which seek to tell the story of the Liberation War. There are four of these on each side of the lawns, then there’s a smaller esplanade where two others flank the large statue of the male allegorical representation of ‘Victory’.

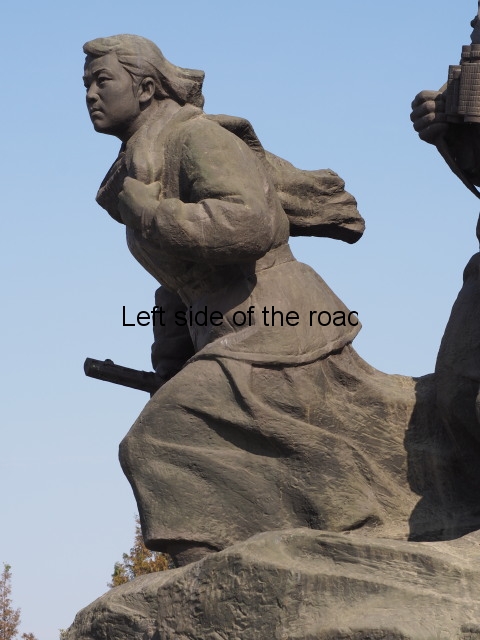

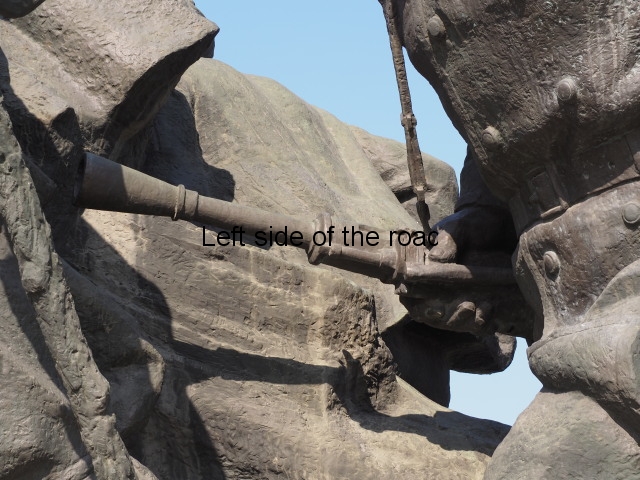

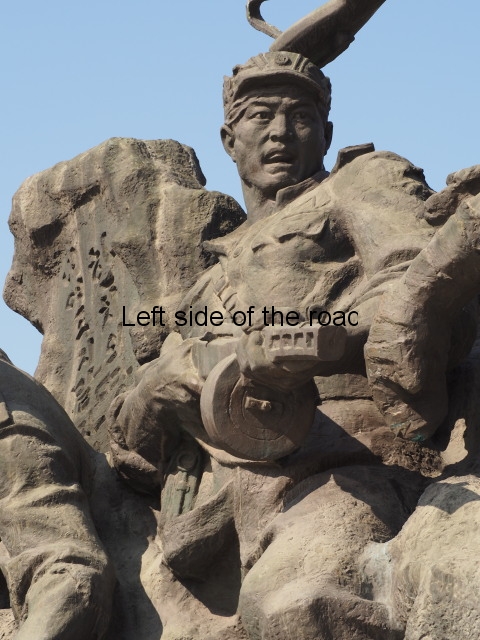

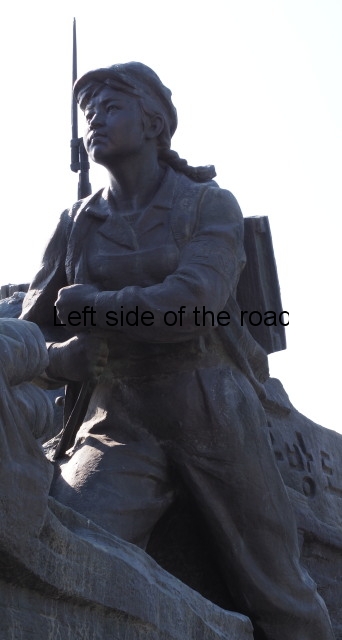

Some of those tableau represent specific battles or campaigns but in general they represent the whole nation’s struggle against the invading, imperialist forces. The three main strands of the armed forces, the army, navy and air force, are depicted as well as the ever important guerrilla forces and the role of the work carried out in the rear. Women are shown (although in a minority) both armed and taking part in battles as regular fighters or guerrillas, but also in supplying the front with necessary equipment and materials. As in the various battles and wars that the Union of Soviet Socialist Republics, the People’s Republic of China, the People’s Socialist Republic of Albania and the Socialist Republic of Vietnam had to fight to achieve and then construct Socialism women played a crucial role in the final victory.

The group statues also illustrate those values that a Socialist country wants to celebrate from those who have fought in the past as well as to instil such values in future generations.

The People’s Liberation Navy

People’s Liberation Army

Liberation Air Force

Women in the Liberation War

Three Generations

Compassion

Civilians are warriors too

Liberation

Sweat of her labour

Behind the group sculptures on the right (as you walk towards the museum building) is a mock-up of trench warfare that leads to open sheds where captured military hardware of the invaders is stored. On the left hand side, behind other plastic trenches, is a collection of the hardware used by the People’s Liberation Army, including the likes of Russian MIG jets and T34 tanks.

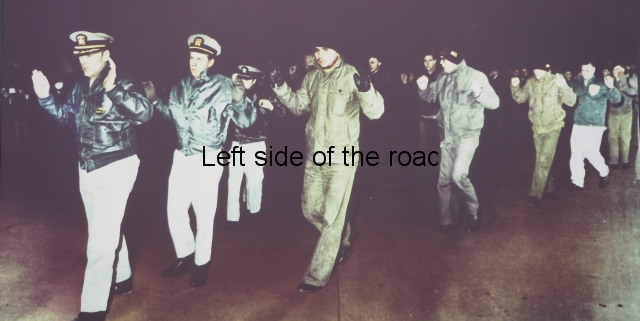

The capture of The Pueblo

January 1968 wasn’t a good month for the US President Johnson or the USA in general, when it came to their foreign ‘adventures’. On the 23rd their spy ship, The Pueblo, was boarded and captured by the forces of the DPRK whilst carrying out surveillance activities in the East Sea of Korea/Sea of Japan. A week later the Tet Offensive began in Vietnam – the one single event in that murderous war that showed the US imperialists that – however much they spent, however many Vietnamese they killed and however many of their own troops would return in body bags or scarred for life – they would be unable to win.

The Pueblo – US Spy Ship

The DPRK, obviously pleased to have achieved such an important propaganda coup, didn’t flinch under pressure from the US to return the boat and its crew and it wasn’t until 11 months later, when the US admitted its espionage activities, that they got their crew back. The ship, no. It is moored on the banks of the River Potong and is now a permanent part of the exhibits of the Victorious Fatherland Liberation War Museum and a visit is always on the itinerary of all visitors to the museum.

However, this episode didn’t deter the US from maintaining spying activities over the country and they faced another disaster on April 15th 1969 when one of their spy planes, EC-121 was shot down and all 31 Americans on board were killed. Now, I’m sure, a number of satellites regularly monitor what’s going on in the DPRK.

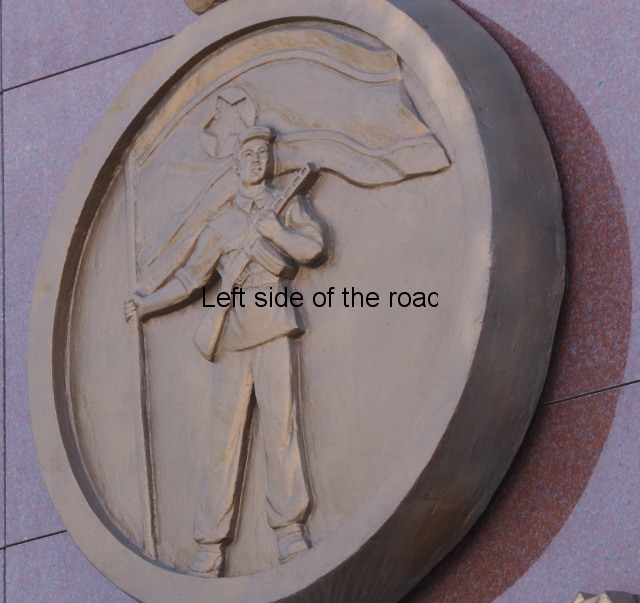

‘Victory’

‘Victory’

The statue of ‘Victory’ is posed in a manner which is common in Socialist Realist military monuments, a soldier going forward but looking behind and calling for others to join him/her in the advance. Here he holds a DPRK flag, his right hand high on the flag pole, with his left arm outstretched behind him, his hand adding urgency to his call for others to join the fight. Hanging from a strap around his neck is a Soviet Shpagin PPSh-41, sub-machine gun, millions of which had been produced in the Soviet Union for the defeat of the Hitlerites in the Great Patriotic War and which were now used in another war against an aggressive, invading force.

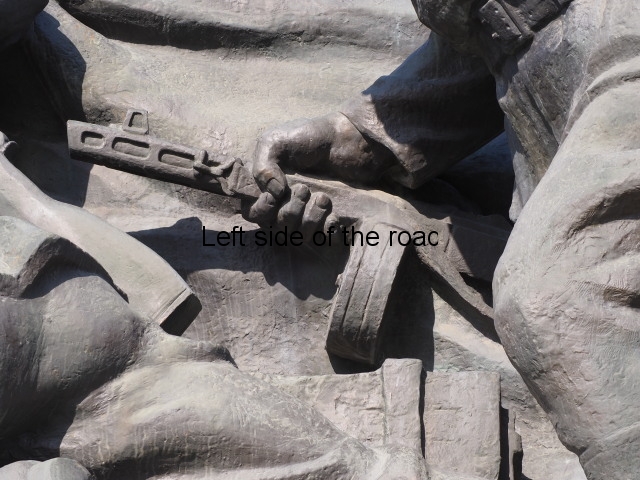

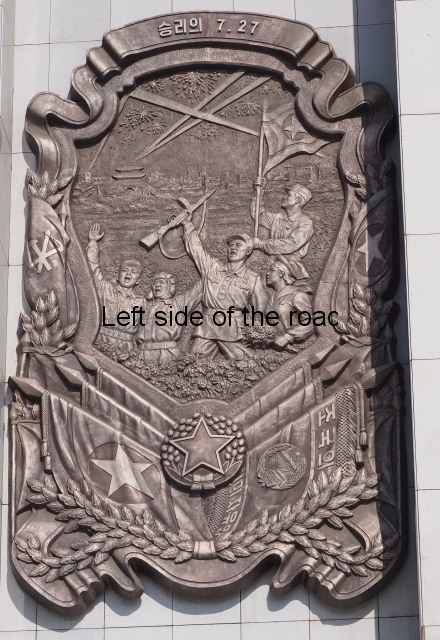

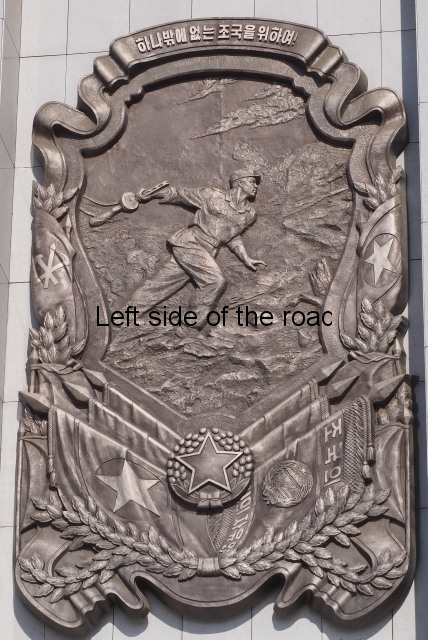

The Museum Entrance Façade

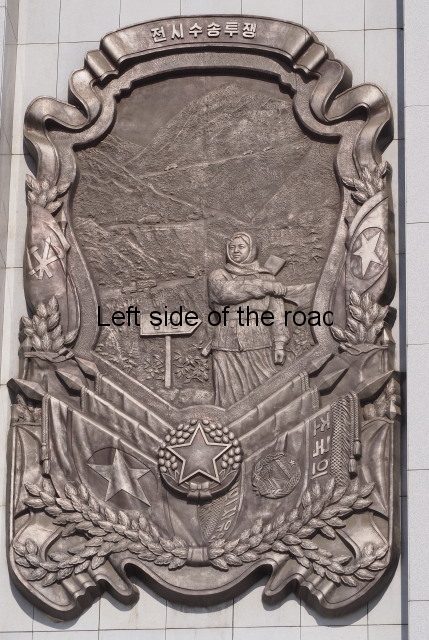

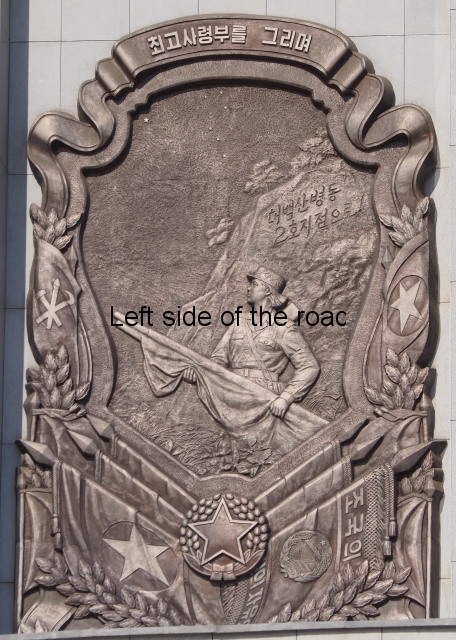

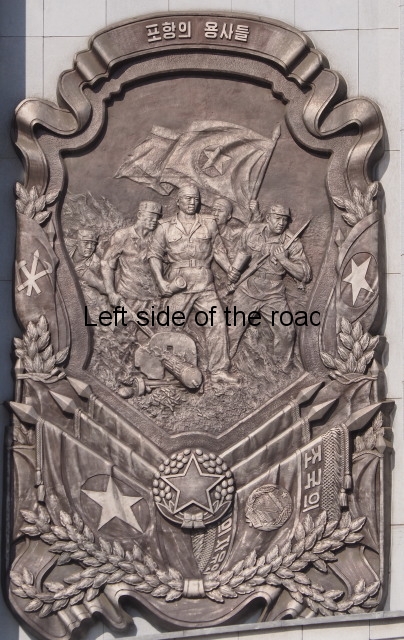

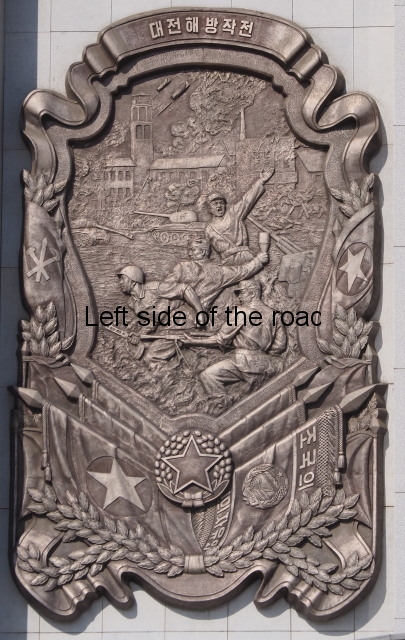

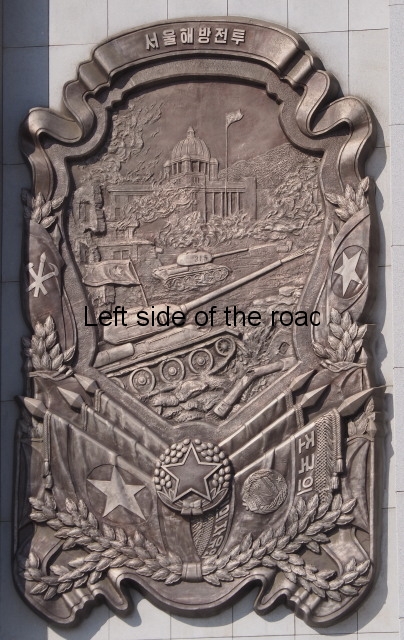

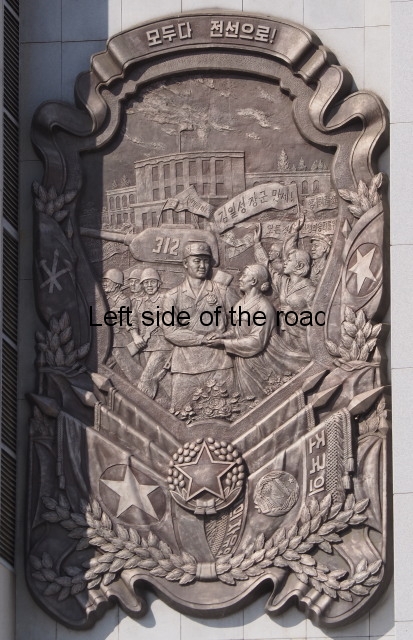

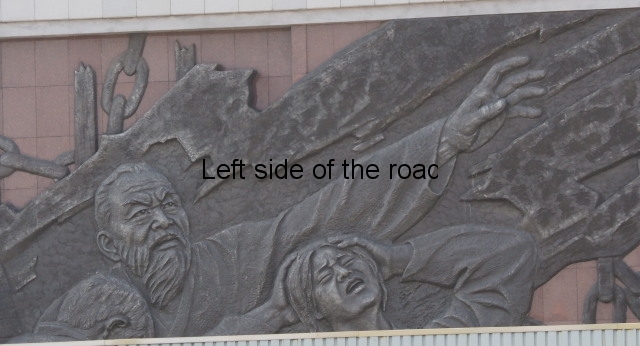

Entrance to the interior of the museum is by a door in the centre of the concave façade just behind the statue ‘Victory’. Before going inside have a look at the 17 large bas reliefs that take up the whole of the frontage. These tell the story of the Fatherland Liberation War, some images reflecting actual events whilst others episodes of warfare that would have taken place during the three years of the conflict. Only one of them has a date, (7 27) the 7th July, and that’s the one on the extreme right, which shows an image of the celebration of the end of the war in 1953. If you have had a look at the statues in the Memorial Park you will notice that certain images are repeated in a slightly different form, but as with the statues all the armed forces are represented and the role of the regular and guerrilla fighters, the old and the young, of men and women are all represented and their achievements and efforts commemorated and celebrated.

All the images in the centre of these bas reliefs are different but the surround are in common – apart from the slogan written at the top. A folded, ceremonial scroll creates the border at the top and to about half way down on both sides. Then, on the right hand side is a furled national flag which just shows the star. On the left hand side a similar banner is folded to reveal the symbol of the Korean Workers’ Party – the hammer, sickle and ink brush. (The Party Foundation Monument is a huge representation of this symbol.) Above and below these two banners ears of ripe rice poke their way into the light.

At the bottom there’s a busy scene. There are three, partially furled banners on each side which rise from the bottom centre to each side of the bas relief, forming a V for Victory. All these banners have a spear shaped finial at the top. At the point where these banners cross there’s a large red star surrounded by ears of rice – similar to the star over the main triumphal entry arch. On the banner closest to the viewer on the left hand side is a large star and on the right the emblem of the DPRK – as described above. Finally, at the very bottom are more ears of rice.

Female guerrilla activity and the Red Star

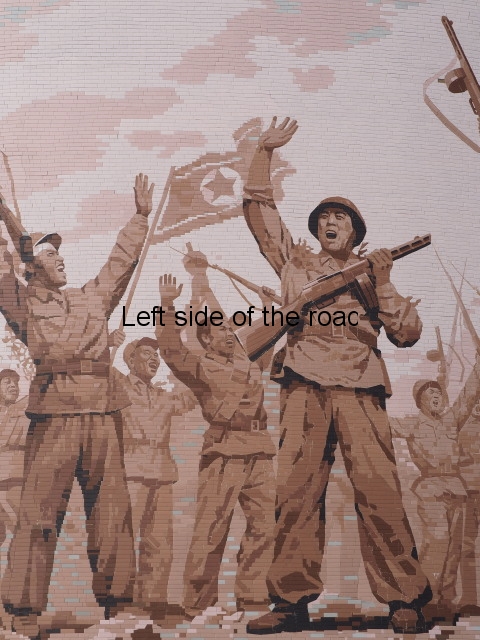

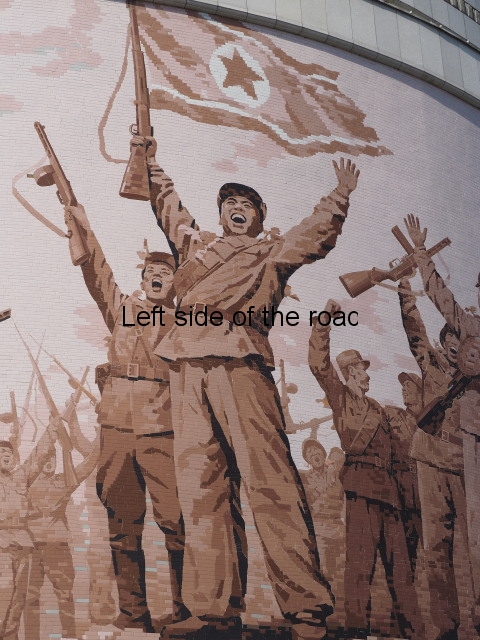

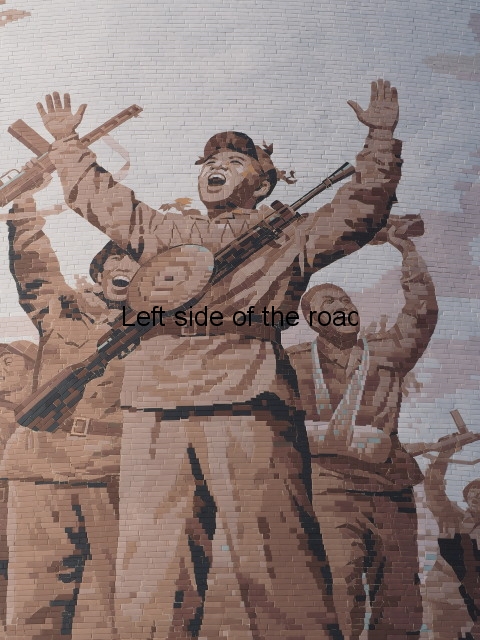

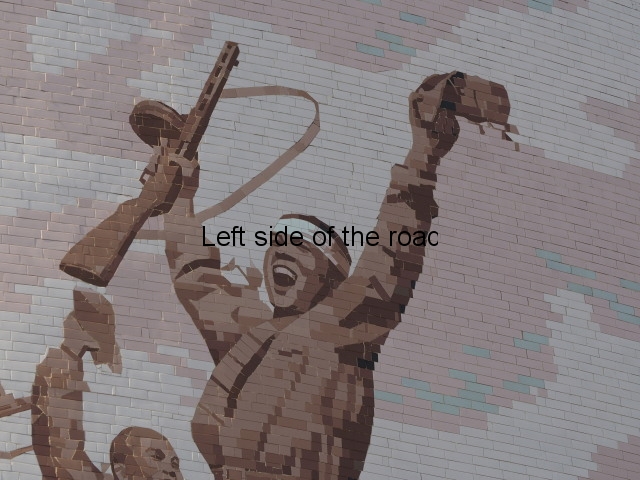

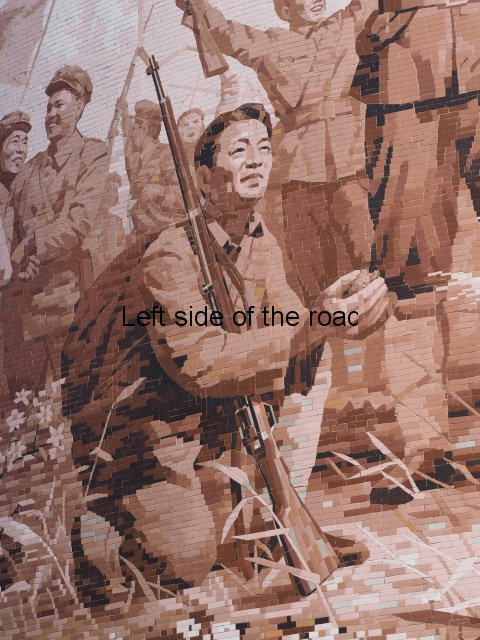

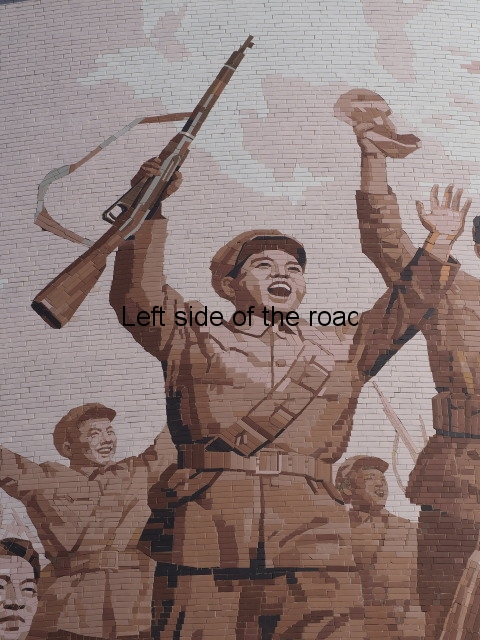

Mosaics

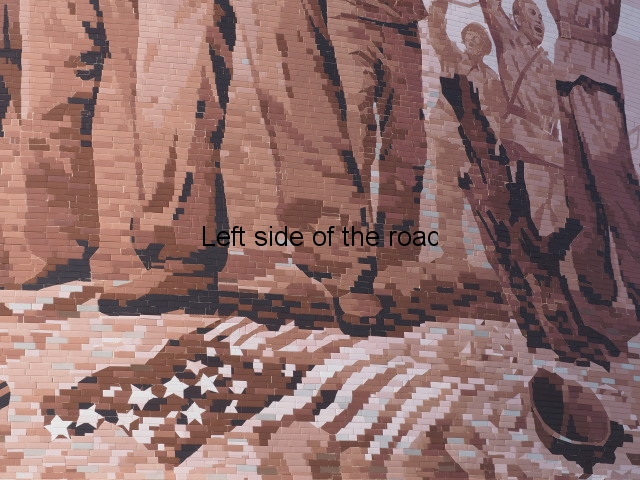

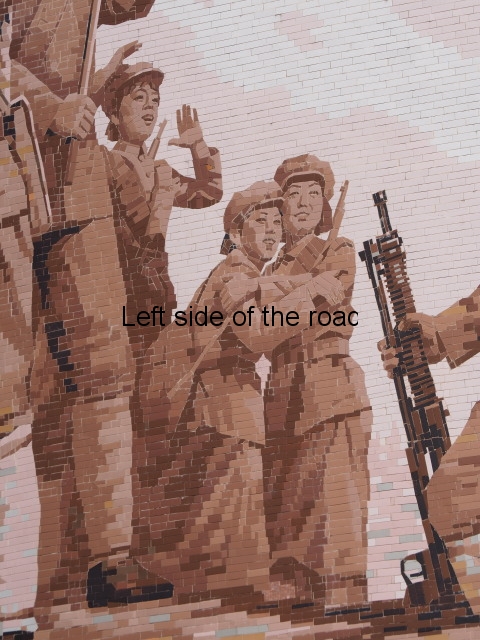

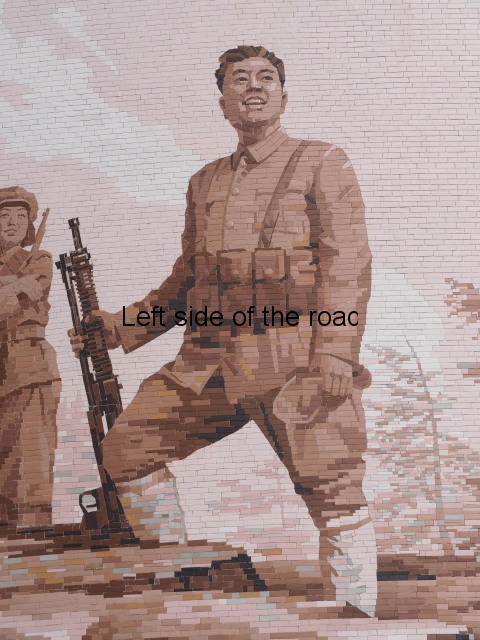

At the right hand edge of the concave facade the wall becomes convex and here there’s a mosaic depicting a victory of the People’s Liberation Army over the US imperialist forces. Flags of the DPRK flutter in the wind and the largest, which dominates the mosaic, is attached to the central figure’s rifle (again another trope that can be seen in Albanian lapidars, for example the statue at Fier Martyrs’ Cemetery). In celebration of their victory the men (strangely all men in this image), some of them wounded and bandaged, have their arms in the air, weapons in hands as they cheer themselves for their success. At the base of the image a tattered Stars and Stripes (the US flag) of the defeated aggressor lies in the dirt. To its left is a discarded helmet of an absent US soldier, the skull and crossbones image indicating that they have brought death to a country where they have no right to be.

US = Death

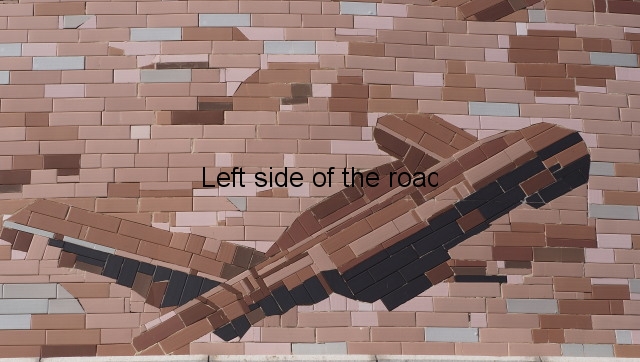

There are many fine mosaics, some of them very large, in Pyongyang and other locations in the DPRK (some of which I will be posting at a later time) but this one at the museum is slightly different. Most of the mosaics use small pieces of coloured stone. Here, on the other hand, the image is almost monochrome as the image is created by a handful of colours (a couple of shades of brown, black, white and a slightly bluish off-white) on rectangular tiles. Some of these are broken but the majority of the image is constructed by a technique that is similar to brick laying, the tiles in a regular pattern. From afar it’s difficult to even realise that it is a mosaic but getting close you can appreciate the artistry of those workers from the Mansudae Art Studio who created these images.

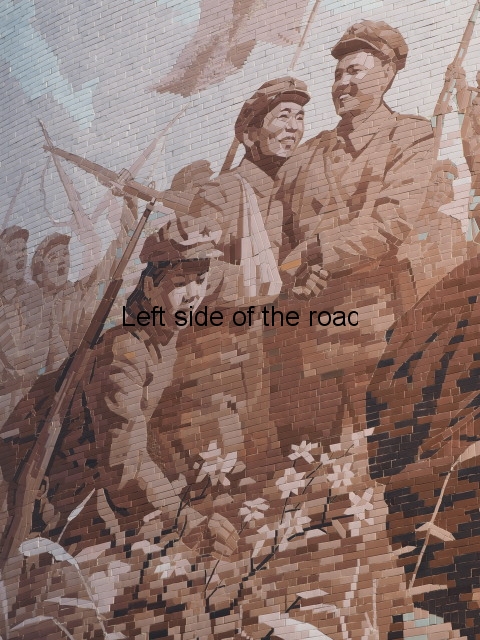

On the left hand side of the bas reliefs there’s another large mosaic. This is, again, a victory scene but this time a group of combatants are on the rocky summit of a high hill. Tall pine trees set the scene but it’s uncertain exactly what has been achieved. Interestingly here the banner is not the national flag but the red flag of Communism. Although a scene of jubilation the feeling is different. Yes there are one or two weapons raised high in the air but the celebration is much more intimate. An older man, who could be the commander of the group, is hugging a young bugler and a couple of young women are also holding each other. You get the impression of what has been achieved is a victory over their own weaknesses rather than that of the enemy – as in the first mosaic.

Victorious Comrades

Kneeling down at the bottom left of the image a male soldier has scooped up a couple of handfuls of soil which he holds in his hands as he looks, smiling, in the same direction as the others. Soil to a peasant is everything and here we are given the impression that these fighters are now the possessors of all they survey.

The rest of the outside

There were many parts of the building, from the outside, I wasn’t able to visit due to constraints of time but I was aware that there were many other bas reliefs on display, especially on the part of the museum extension that was completed in 2012.

The interior

It’s not permitted to take pictures inside the museum but you can get an idea of what is presented from book Victorious Fatherland Liberation War Museum, published in 2014. Unfortunately, although an English version exists (the introduction at the beginning of the blog comes from that version) it’s not available for download. To get a copy which shows the same images but with captions in Korean go to Publications of the DPRK.

Who started the war?

No one ever starts wars – or, at least, it’s always the other side. That obviously is impossible. War is the extension of politics by other means and truth is always the first casualty of war. Whatever answer you give to this question in relation to the Fatherland Liberation War, as well as in what you might call that particular conflict, is equally a statement of political allegiance.

I don’t intend to go into any depth here about the conflict between 1950 and 1953 – which, in theory still exists. An armistice was signed, not a treaty. However, as this post is about the Museum in Pyongyang that celebrates the achievements of the workers and peasants of the north in that war I don’t think it can be completely ignored.

So a few points:

- The idea of ‘drawing lines’ at the end of World War Two might have seemed like a good idea at the time but it’s long-term effects have been disastrous for many millions of people. I believe this was agreed by the Soviet union as an attempt to prevent war – the problem the agreement was made with imperialist powers who were not prepared to give up what they had or wouldn’t be prevented from acquiring more control in those parts of the world where the weakened European imperialist could no longer guarantee their control of the old colonies.

- Although prepared to support the DPRK against imperialist aggression both the Soviet Union and the People’s Republic of China were tired of war and it made no sense to instigate another confrontation with the capitalist states so soon after such destructive wars in their respective countries. The US had no qualms about this having benefited from the World War Two and feeling that it had the right to decide what peoples’ should do and what system they should live under.

- It was under US instigation that aggressive border controls were set up along the 38th parallel in 1946, restricting movement and creating needless antagonism in the border region.

- The US constantly went back on agreements when they could get a way with it. In Korea they supported the ultra-right, ultra-nationalist, neo-Fascist Syngman Rhee who would be a willing tool in the attempts by the US to destroy any attempts to construct Socialism in the Korean peninsula. (It should be remembered, when many people refer to ‘Democratic’ South Korea, that Rhee and his successors were virtual dictators of the country and it wasn’t until 1988 that any sense of a parliamentary system was instituted in the country. During all that time the country was supported militarily, politically and economically by the US – with no criticism of a dictatorship.)

- Korea was seen by the US as a place where they had to stand against the spread of Communism, especially after the success of the Communist Party of China, led by Chairman Mao, and the creation of the People’s Republic of China in 1949. The failure of the US (and its UN puppet supporters, such as the UK) to defeat the DPRK in the 1950s was to lead, inevitably, to the US involvement in Vietnam in the 1960s.

- Although tensions were high at the beginning of 1950 overtures from the DPRK for nationwide elections were summarily rejected by the puppet regime in the south. Only a spark was needed to ignite a full confrontation but the south (with American support) made no attempt to reduce the tense atmosphere.

- The U.S. Diplomat John Foster Dulles visited Korea on 18 June 1950, seven days before hostilities broke out. Syngman Rhee would have done nothing without US approval and would also do whatever they required.

- The US sought ‘legitimacy’ from the United nations, securing a resolution of the Security Council on 7th July 1950. The USSR at that time was boycotting the UN in support of the seat on the Council reserved for China was held by the Nationalist Government in Taiwan and denying hundreds of millions of Chinese representation in the international forum. The US doesn’t always need UN support (and had not called for it in the previous five years in their wars of intervention and didn’t call for it in Vietnam) but it helps in the propaganda war to have a piece of paper to justify the killing. When they failed to get such a resolution in 2003 they invaded Iraq nonetheless.

For more detailed ideas of how the war is seen by the DPRK have a look at The Korean War – An unanswered question. If you want the point of view of the ‘victim of aggression’ – the put upon United States – I’m sure you will find justification in spades.

Further information

The attempted isolation of the DPRK means that it’s not very easy to obtain information about the country from the country itself – most information in the west being filtered through antagonistic capitalist media outlets. For those interested in the opportunity to see the DPRK from another perspective go to Publications of the DPRK where there are a number of language options (although not all books and pamphlets are necessarily available in all those languages).

More on the DPRK