Chapter 15 – Glaisdale to Robin Hood’s Bay

The last day – and the first without a pack!

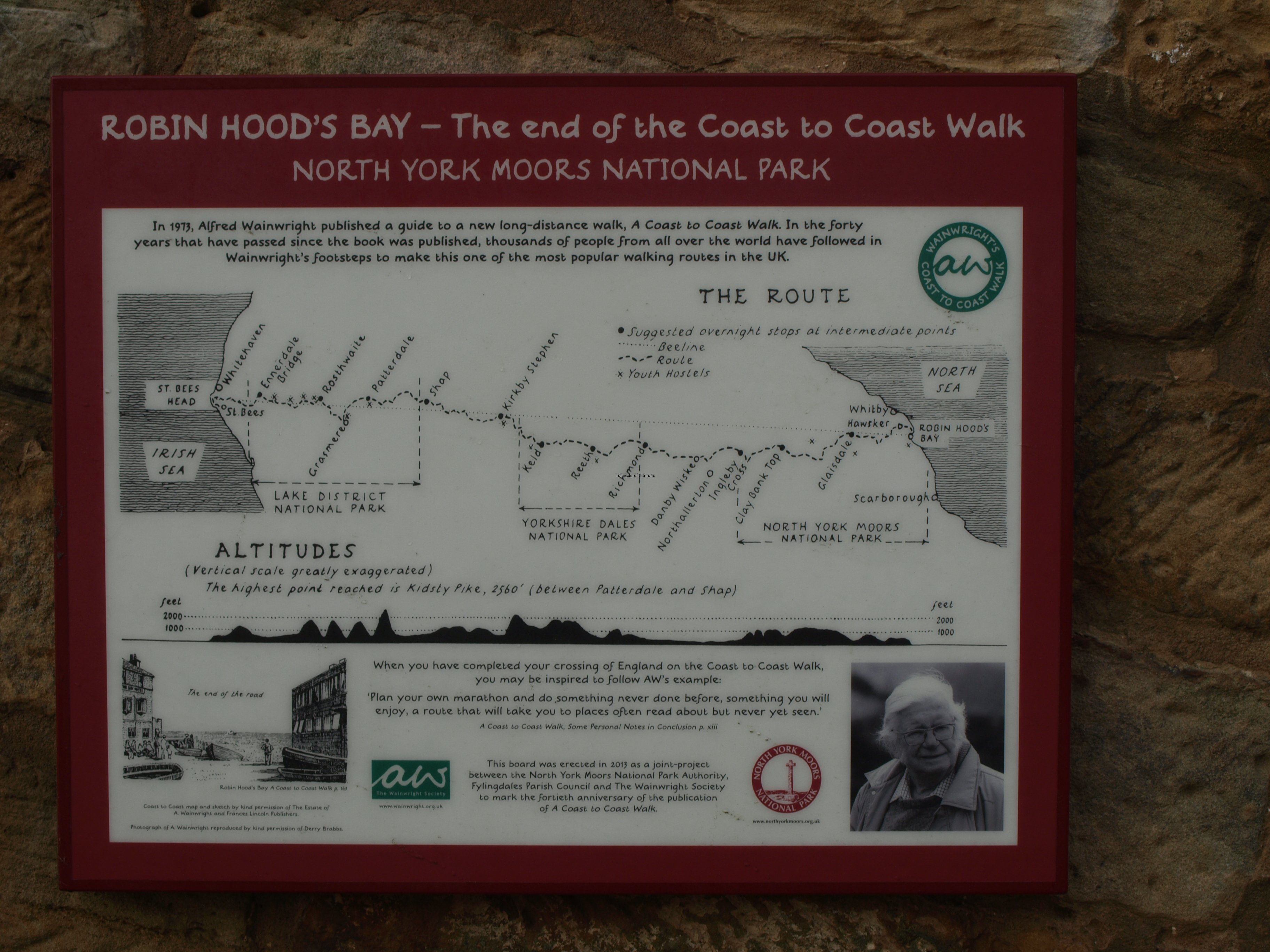

It had taken a long time in coming but the final day had arrived. Today, baring any disaster, walking from Glaisdale to Robin Hood’s Bay I would finally reach the North Sea and the end of the walk. (Whitby is on the coast of the North Sea but the wrong bit as far as the Coast to Coast walk is concerned.) But it wasn’t just a stroll. This was still a serious walk and I estimated I had close on 29 kilometres before I could say that I had finished the whole of the long distance walk.

First I had to get back to where I’d finished the day before. There was a bus but that would have meant a late start so the option was the train back along the same route I’d taken the previous evening. In the Arncliffe Arms in Glaisdale I had been told that the train is, in effect, the local school ‘bus’ first thing in the morning and at mid morning and this was evident at the station when close on a hundred school children must have walked through Whitby station. But that’s a good thing as it means, at least in term time, that the train would be almost guaranteed to run and not being subject to arbitrary cancellations.

Although the weather was, yet again, dull and overcast this is still a pleasant train journey. The eventual destination along this line is Middlesbrough but going inland and through the hills rather than along the coast, the quickest way from Whitby. In the summer months, or just on a bright and sunny day in whatever season, this would be a worthwhile journey. The only thing I can’t work out about it is why it’s cheaper to go up hill in what is considered peak times than it is downhill in off-peak times.

The scheduled journey time is only 27 minutes so I would be starting to walk, more or less, at a similar time I had adopted from the start.

A very slight diversion at the very beginning of the walk is a visit to the so-called ‘Beggar’s Bridge’ (quite a beautiful bridge with the vegetation growing on it), built-in 1619 specifically for pack horses, and which is one of a number that cross the Esk River, the route of which the railway line follows as it heads further in land before turning north towards Middlesbrough. I don’t realise this at the time, taking a picture of the information board but not taking the time to read it and so didn’t look out for two of the other bridges in the villages of Egton Bridge and Grosmont I would have to pass through on my trek east.

As I wasn’t carrying a rucksack all I considered I might need had to be either worn, in the pockets or around my neck as I didn’t have a day pack. For some reason, even though I’d been ‘dreaming’ of this freedom I didn’t actually feel free as I followed the path through the woods on the banks of the river. Also I wasn’t moving as fast as I thought I would. My timings for the stretch from Glaisdale to Egton Bridge were based on a load and I barely kept to those times. I don’t think that was anything other than the inability to adopt my normal walking pace. For so long, 12 days, I had forced myself to just plod along and it seemed as if I couldn’t get out of second gear.

(The previous day I had considered walking to the next station down the line after a quick pint in the Arncliffe Arms. Fortunately that plan was quickly forgotten as I relaxed in the bar otherwise I might had made a bit of a faux pas as the station in Egton Bridge is at the far end of the village and I might have cut it too fine to catch the last train to Whitby.)

Before leaving Egton Bridge there’s a large church, not that far from the railway station and just a very short diversion from the path. I decided to try the door and was slightly surprised it was unlocked, there seeming to be no one around. Obviously in some parts of the country churches are opened on a regular basis for the occasional passers-by, but I’m not used to that in the north-west. What I found interesting was the frescos in the apse, behind the altar, it not being usual to find such paintings in churches built-in the 19th century. In trying to find out more about the church later I discovered that the ‘stations of the cross’ were in the form of painted reliefs on the outside walls of the church, something I’ve not come across before. I took a few minutes to go inside but obviously missed a lot. Also read that this huge church for a very small village (and it’s not the only church) has been nicknamed ‘The Cathedral of the Moors’.

The next village (the walk today would pass through a few of them) was Grosmont. Again a small village but perhaps with three things that make it different: Grosmont is pronounced with a silent ‘s’ and ‘t’ – presumably some French connection – for all I know other letters might be silent in the local dialect; it’s the terminus of the North York Moors railway, which operates steam locomotives. It seems it was this train that was used in the ‘Harry Potter’ films – not a franchise I found particularly interesting or memorable; and there’s one hell of a steep hill you have to climb to get out of the village if doing the C2C.

It’s a quiet country road, with limited traffic but it’s still a bit of a shock to the system as the climb goes on for close on 2 kilometres. Towards the summit of this climb (which allowed a view of Whitby and the distinctive abbey ruins in the distance to the north-east and a ‘welcoming’ strong and cool wind as you arrive at the moors) there was something else I’d never seen in real life – a hedgehog escape ramp from a cattle grid. Top marks for thinking about the poor hedgehogs but I’m not sure that the positioning of the tyre (presumably to protect the fencing) made life that much easier for the erinaceina.

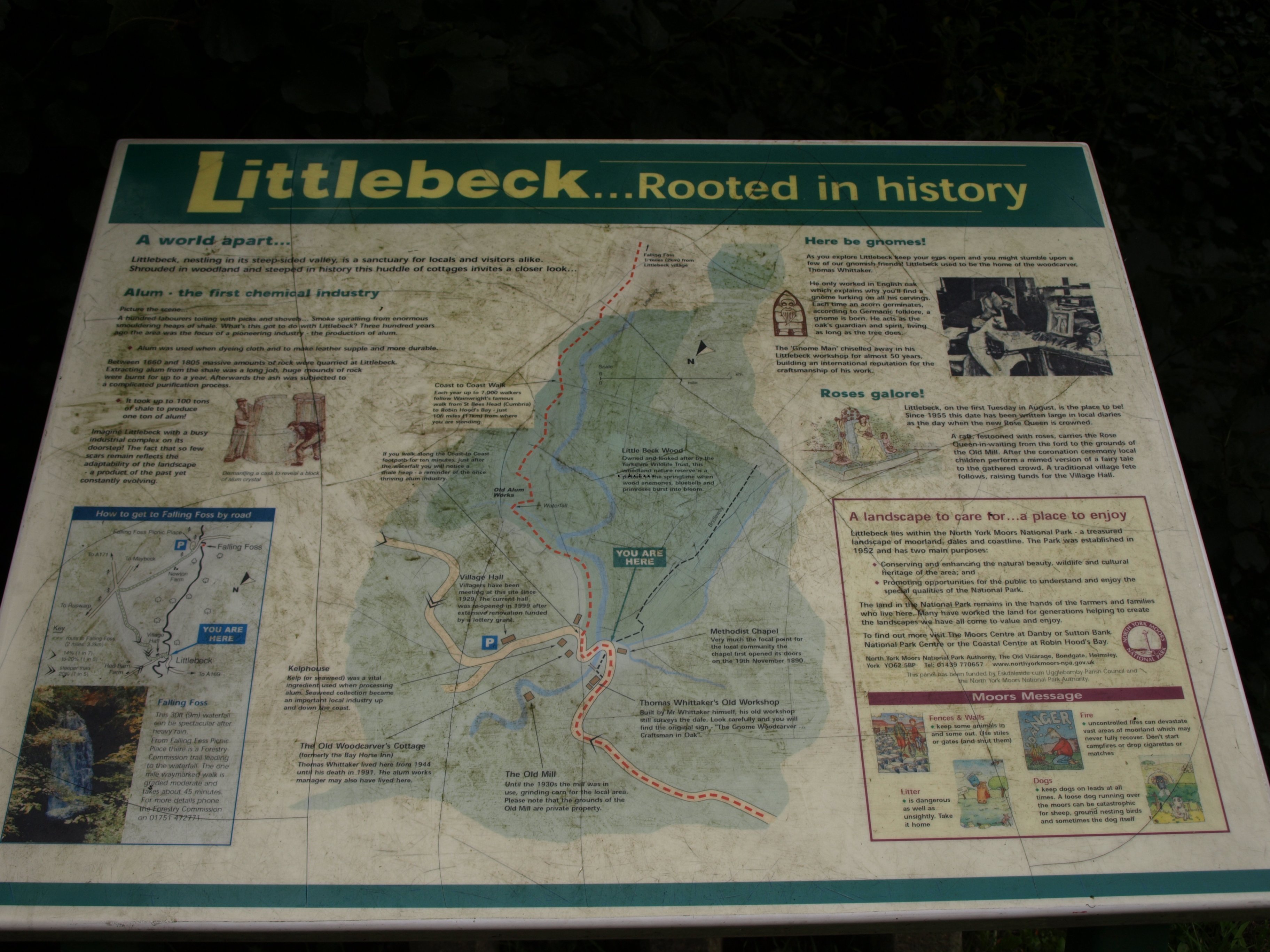

After a relatively short stretch across the moor the path heads down to the very quiet village of Littlebeck and from there into the Littlebeck Wood, a local nature reserve. This is so different from the moors that have dominated the route for the last 3 or 4 days. And a welcome respite from the constant wind that I have been walking into on heading east. This path through this nature reserve is about 3 kilometres long and heads only slightly SE so you’re not making much progress towards the sea but would be a welcome break if doing this walk on a hot and sunny day. Although closed by the time I passed through (but only by a matter of days) there is a café next to a small waterfall (probably much more impressive after a lot of rain) as well as a Victorian folly, a huge rock carved out to produce what is known as ‘The Hermitage’. A few drops of rain started to fall as I walked through this wood and feared that once out in the open I would have to face unpleasant weather (something I’d miraculously avoided so far), but nothing came of it and amongst the trees I was unable to get any idea how the weather that day was developing.

But this green and sheltered section gave way to the open road and then a couple of stretches of open moorland. But this is not an area where you can just follow the most direct route and the path often takes the opposite direction to the way you want to go as this is the only way to get through without wading up to your knees in bog water. Again, even though I was beginning to find walking into the wind tiring these unusual weather conditions were drying out the land and the relatively dry summer meant I was probably passing through in the easiest of conditions underfoot.

I left the moorland behind me for good, on the Coast to Coast, once I had picked up the quiet road that leads to Hawsker, the last village before the true end at Robin Hood’s Bay. The pub there was closed, fortunately for me as a delay there would have blown all my plans apart – although it was only as matters developed over the next two or three hours that I came to realise that. The main road north to Whitby passes through Hawsker and I would be lying if I said I wasn’t tempted, when I came across the bus stop, to leave the last section till the following day and instead head to Whitby for my baggage – but I rejected such a cop-out and trudged on. As I left the main road and headed for the coast a there was a sign post indicating that Robin Hood’s Bay was 2.5 miles away. It was a little bit of despair that after about another 30 minutes quite brisk walking I came across a signpost that indicated 3 miles. This is due to the fact that the official path follows the cliff path to then drop down to the sea but to get there you have to head north through the caravan and camping sites, completely deserted of people when I passed through but, I’m sure, heaving in the summer.

It had already been a long day and as I came to each headland on the cliff path I hoped that I would get my first view of the village. My problem, self-created in that I had left my rucksack in Whitby, was I was working around bus timetables and as time went by my options were reducing. But I didn’t do myself any favours in this respect.

On finally reaching the edge of the town I walked past the bus stop that would take me to Whitby and anyone I asked was a visitor and couldn’t answer my query – why is it that when you need some important information about a location that the only people you come across can’t give it to you? Anyway, by the time I got the necessary details I was then in a pub at the water’s edge and had missed the bus I wanted to catch. Even though I had the time for a very quick pint, and I had actually completed the whole of the walk, having walked past the signpost that is at the bottom of the steep hill in Robin Hood’s Bay, there was no real sense of achievement or celebration.

I couldn’t relax as I had to head seven or so miles north to recover my belongings. If I had taken a step back and really considered the options I could have left my gear in Whitby, had headed to the YHA with what I stood up in and then made the bus trips the following day. But I didn’t so that’s the way things go. But the diversion to the pub did provide me with important information and that was the quickest and most direct route to Boggle Hole. There’s a path along the cliff top but at low tide it’s also possible to reach the bay along the beach – and as luck would have it that afternoon the tide was on the way out. Still didn’t know exactly where it was but at least I knew that I would eventually get there on the sandy route.

But before that I had to get to Whitby. The bus was easy, it was the rest that was difficult. I realised as I looked at the timetables that I had 23 minutes after arriving in the town to get up to the abbey ruins, collect my bag and then get down to the bus station. That meant an extremely brisk walk and an almost run up the 199 steps, a short prayer that someone would be at the reception so that I could get in and out again with my bag and then follow the same route back to the bus stop. I did it with about a minute to spare.

And this mad rush was after 7 hours walking and just under 30 kilometres. Not the relaxed and triumphant ending I had been expecting. There was another bus a couple of hours later which would have allowed me to experience Whitby’s famous fish and chips but would have led to an interesting walk along the beach to my bed. This rushing about was the only really downside of having a rucksack free day but, all in all, worth it. But I’ll have to make a return visit to Whitby in the not too distant future. It was a place I immediately warmed to although my time there was so short.

It was getting dark as I headed along the beach, once more back in Robin Hood’s Bay, to the hostel. Fortunately the woman I asked for more accurate information in the gloom beside the North Sea didn’t a) panic and run or b) was a local so knew what I was after. So after all that messing around I finally got to the location of my bed for the night at about 19.30.

The Coast to Coast route had been successfully completed, not without a certain amount of pain (but not too much), without truly adverse weather and with everything going, more of less, to plan.

So at 19.15 ish on the evening of Wednesday 2nd October it was 192 (approximately but most certainly more) miles down and no more miles to go.

Practical Information:

Accommodation

Boggle Hole YHA. The best thing about this hostel is its location. It’s in a small cove very close to the high water line and that must be interesting on a stormy day in winter. Boggle is a local name for a goblin that is also supposed to haunt the place – but not on the night I was there. The building was originally used as a water powered mill and before that the cove was supposed to have been a smugglers favourite but it seems to be too close to the village of Robin Hood’s Bay for that. At the same time giving a place a name that will frighten the ignorant and superstitious was a well-known tactic of smugglers.

I originally planned to stay for a couple of nights, the one on arrival and a final ‘rest day’ but decided to cut my losses and run when I had to find somewhere else to stay when a drunken slug arrived just after I had turned out the lights. He fell asleep immediately and then proceeded to snore like a drain. I hadn’t enough alcohol to sleep through it and didn’t want to risk another nigh, and anyway didn’t really need to relax after the walk. If the weather had looked more promising I might have stayed but the greyness seemed set for some more days. The YHA did a special deal if you stayed for two or more nights and that came to £34 for 2 nights B+B. And for fans of ’60’s music, Jimi Hendrix stayed in one of the outhouses – presumably before it was a youth hostel.

An issue with the YHA and its relationship between school groups and the rest of the population arose at Boggle Hole in a strange way. The main building had been virtually taken over by a large group of 16-17 year old school girls. The few of us not in the group were ‘banished’ to a modern annex, all well and good. When I went to the main building to use the wi-fi I was directed to the common lounge area. There was a room directly off this lounge that I, at first, led to a work room and that some of the girls were working late on a project – there was a classroom close by. It was only after a while that I realised it was a dormitory and they were getting ready for bed. The YHA could think a bit more about such arrangements to make it more convenient (and socially comfortable) for all concerned. But that would take forethought which is so sadly lacking in many aspects of British society.