Coba – Quintana Roo

Location

The pre-Hispanic settlement of Coba is situated in the north-east of the Yucatan Peninsula, in the state of Quintana Roo, 47 km from the Caribbean Sea. It comprises five lakes – Coba, Macanxoc, Xcanha, Sacalpuc and Yaxlaguna – and still boasts part of its rich vegetation and wildlife in a state where tourist resorts are rapidly encroaching on the natural environment.

Pre-Hispanic history

Several of the inscriptions found at the site confirm that in this case – a very rare occurrence – Coba is the original name of the city. One of the possible and, given its proximity to the lakes, most plausible translations is ‘ruffled waters’. The city of Coba covers an area of approximately 70 sq km. In this region with its absence of surface water, the presence of the lakes must have played a crucial role in the development and survival of the city and its population. The city boasted a large network of sacbeob or raised stone causeways, of which about 50 have been recorded. The length and width of these ‘white roads’ vary: some serve as internal connections for groups of buildings, while others link distant cities and regions. Such is the case of Sacbe 1, which is 100 km long. The classical architecture of this city is more akin to the predominant style in the Peten region of Guatemala, rather than to that of northern Yucatan. The inhabitants of Coba who did not belong to the ruling class lived on the outskirts of the city, in dwellings very similar to those used by the present-day Maya. The first settlements recorded date from the Late Preclassic, and although no constructions from that period have been found to date, they probably took the form of villages on the edges of the lakes, with an economy based on farming and hunting. In the Early Classic, Coba exerted economic and political power over several nearby communities. The road network and most of the stelae at the site date from the Late Classic. Between AD 800 and 1000, the city experienced a construction boom and extended the road network; meanwhile, relations declined with the Peten region and increased with the Gulf coast. By the Postclassic, the city’s hegemony was on the wane and it fell under the influence of more ‘Mexicanised’ groups. The existing buildings were remodelled in the new ‘East Coast’ architectural style, which became the common denominator of coastal sites such as El Rey, Xelha, Tulum, Xcaret, etc.

Site description

Coba group.

This large group of buildings, the oldest in the city, is situated between two lakes and several sacbeob leading off in various directions.

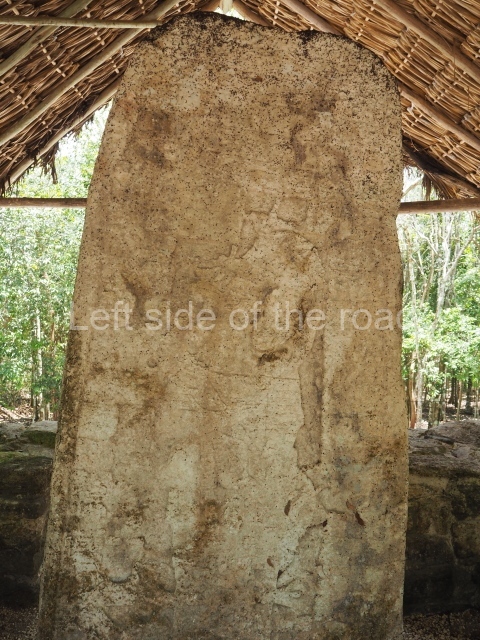

The acropolis, which comprises numerous buildings and superimpositions, must have been the most important complex for hundreds of years. Although only a small part of it has been explored and is open to visitors, there are several notable constructions. The iglesia (‘Church’) stands 24 m high and is the second tallest construction at the site. It comprises nine rounded tiers and has been altered and added to on several occasions over the years, for example by stairways which cover earlier versions, terraces with rooms along the sides, etc. Its earliest construction phase dates from the Early Classic, while the latest addition corresponds to a Postclassic adoratorium at the top of the structure. At the foot of the building, opposite the stairway, is a fragment of the upper part of Stela 11 and a round altar in front of it. Although most of the carving has been eroded, it is still possible to distinguish a few square panels which corresponded to glyphs. Opposite the Iglesia, a little to one side of it, are two courtyards formed by elongated buildings which in their day must have had vaulted roofs. A long seating area culminating in a vaulted stairway leads to the two courtyards. The stairway may also have been used for watching important events in the main plaza of the group. Its steps were decorated with modelled stucco and painted in bright colours. Fragments of Stela 12 stand at the south end of the seating area, and one of the two Ball Courts at Coba is situated alongside the Acropolis.

The ball court comprises two parallel volumes open at the ends and with sloping walls rising from a long bench that delimits the narrow playing area. There are two rings jutting from the top of the volumes. Embedded above the slope of the west volume are two panels depicting prisoners, and on the opposite side a panel and a stone plaque at the centre. The two Ball Court volumes are different: the one on the east side has two stairways leading to vaulted rooms at the top, while the west volume appears to have been surmounted by a construction made of organic material. Behind this volume are the fragments of two stelae, erected during the Postclassic when the Ball Court was no longer used. The Maya ball game was a ritual symbolising the struggle between life and death, the struggle between two opposing forces. It often took the form of a divine trial for settling disputes, and occasionally was staged merely for entertainment purposes. Situated opposite the Ball Court is the

Kan stairway, named after the kan glyphs visible on the some of the steps. It is flanked by two human skulls.

Group D.

Of this large group situated between sacbeob 4 and 8, the Paintings Group, the Ball Court, Sacbe I and the Xaibe are open to visitors. This group contains numerous constructions dating from the Postclassic, the last period of occupation.

Paintings group. The group takes its name from the traces of murals found on the walls of two structures.

Building 1 is the tallest and is surmounted by a small vaulted temple with traces of a mural depicting farming rituals. At its foot, mounted on the stairways, stands structure 2 ; part of the vault has collapsed and inside is a fragment of Stela 27.

Structure 3 is an elongated chamber with columns that must once have supported a wood and straw roof; opposite them are 13 small altars on which the incense burners used for rituals would have been placed. Alongside Structure 1 stands

Structure 6, whose function has not yet been confirmed. It consists of two chambers, nowadays minus their roof, abutted to a square platform. Further west, almost at the centre of the group, is

Structure 4, a low platform with sloping walls and a wide frieze around the perimeter. Stela 26 stands on one side of the structure; although nowadays greatly eroded, it represents a richly garbed personage holding a ceremonial staff and standing above a group of prisoners, framed by glyphs. A little further west stands

Structure 5, an example of the talud-y-tablero (‘slope-and-panel’) style of architecture, and adjoining it a long, stepped platform culminating in a small room with columns. At the top of the stairway is Stela 28 which depicts a scene very like that of Stela 26.

Ball court. This is very similar to the Ball Court in the Coba Group, displaying common traits such as rings on each section and panels depicting prisoners embedded in the slopes. However, in this case there are various unique features, including markers above the court used for scoring points during the game. The central marker represents a human skull, beneath which a rich offering was found, while the one at the end is a disc featuring the image of a decapitated jaguar. The most important feature of all is the enormous hieroglyphic tablet at the centre of the slope on the north volume. The 74 glyph cartouches it contains make reference to two historical moments in the city’s existence, and there are three mentions of the name ko-ba-a, the toponym of the ancient city. Next to the building are the replicas of two panels that once adorned the construction, although the exact place is not known. One of the panels represents a ball game player holding a cruciform object.

Sacbe 1

As you head towards the Nohoch Mul Group, you will pass alongside the beginning of Sacbe I, 100 km long, which leads north-west to Yaxuna, an ancient Maya city not far from Chichén Itzá. This is the longest of all the causeways found at Coba.

Xaibe

This unusual building from the Classic period which the archaeologists have named xaibe (‘crossroads’) is situated very close to the point where several sacbeob converge. It adopts the shape of an apse, with four sloping tiers culminating in a cornice. In the Postclassic it gained a small stairway leading to the landing between the first and second tiers and a fragment of stela, delimited on each side by a low wall, lending it the impression of a shrine. The tiers are inset into the main body of the building, simulating a stairway, but it is obvious from their dimensions that they could not have been used for this purpose. Although there is general tendency to ascribe an observatory function to all round buildings, no evidence has been found to support that hypothesis in this case. Its function therefore remains to be confirmed.

Nohoch Mul group

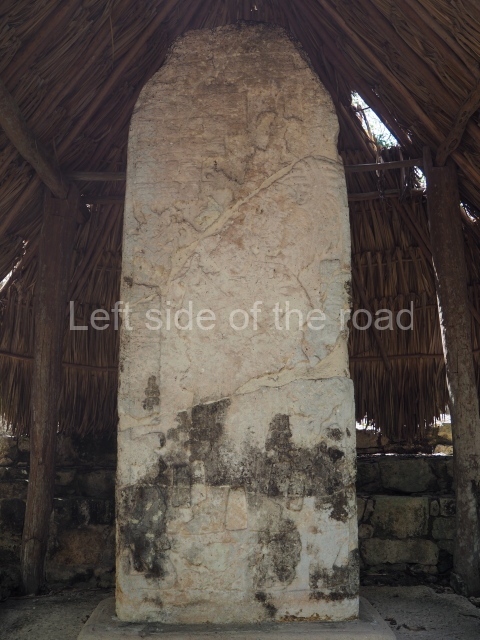

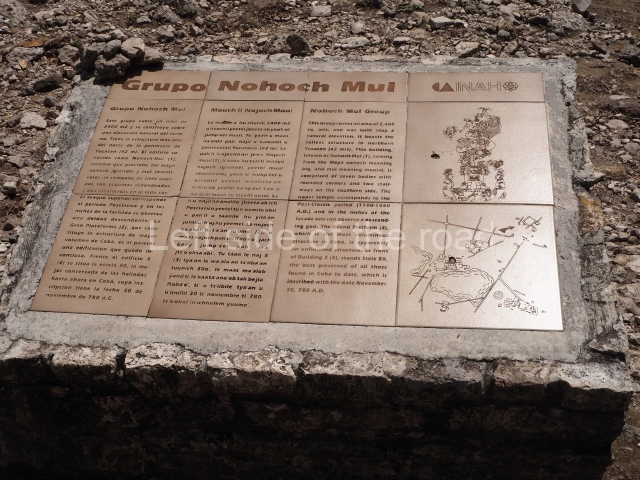

This group consists of numerous buildings, but only three of them have been excavated and are open to visitors. Nohoch Mul means ‘large mound’ in Maya, and the name is a reference to

Structure 1 which stands 42 m high and is not only the largest of this group but also the tallest such structure in northern Yucatan. This grand building has two stairways at the front; one rises to the temple at the top while the other one runs in parallel to the former but stops at a lower level. The construction consists of a seven-tier platform with rounded corners and a temple at the top in the typical Postclassic architecture: inset lintel and a frieze with simple moulding and niches containing scenes of a diving god, once painted in red and blue. Inside the temple, a bench occupies half of the space. The parallel stairway leads to a vaulted room where a stela fragment embedded in the floor was found, with carvings on the front and back. Next to the main stairway, two rooms adjoin the large platform but at different levels – one at ground level and the other at the height of the first tier. Only the front and part of the sides of this large building have been excavated. In the vast plaza associated with this group stands

Structure 10, a platform with rounded corners and the remains of a construction with two rooms at the top; the vault that covered them has collapsed and only part of the walls are still standing. Stela 12, the best preserved of all such monuments found at Coba to date, stands opposite the stairway. It depicts an elegantly attired dignitary holding a large staff with both hands. The feet rest on the backs of two prisoners, while two more prisoners flank the scene. The date mentioned in the glyphs is 30 November 780 of the Common Era, the latest date recorded on the monuments at Coba. Situated in the same plaza is

Structure 12, a low platform with a sloping wall, opposite which stands Stela 21. A chamber was found inside the structure, possibly to accommodate a tomb, but to date only small offering without any human remains has been found.

Macanxoc group

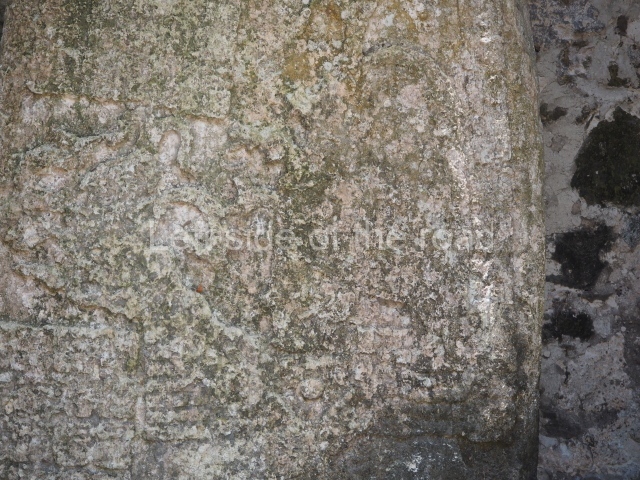

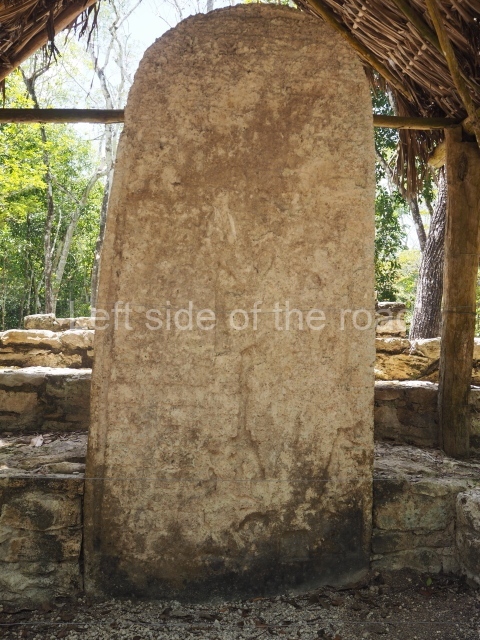

This group of buildings is reached via Sacbe 9, the widest causeway found at Coba. The group sits on a large terrace and comprises constructions of varying dimensions, most with ceremonial functions. There are 8 stelae in the group and 23 altars associated with constructions that vary in size and shape. Most of the stelae are greatly eroded and it is difficult to make out the scenes they depict. However, they all share the same theme: a richly attired personage in the middle, holding a large ceremonial staff or sceptre against his breast, with prisoners at his feet and/or sides.

Monuments and ceramics

Stela l

Sculpted on all four sides, this is the first such monument you come across when you reach the latter group. It stands on a platform with stairways on all four sides and contains 313 glyphs that make reference to four dates related to our calendar: 29 January 653, 29 June 672, 28 August 682 and 21 December 2012, the latter date corresponding to a winter solstice. The first three denote important events that happened in Coba in the 7th century AD, while the last one refers to a date yet to come.

Stela 4

This is situated inside a small vaulted shrine on the stairway of one of the largest buildings of this group. The text is composed of 132 glyphs that mention the date 19 March 623, coinciding with the vernal equinox. The Maya would erect these large blocks of stone to record the names of governors, important events, births, alliances, deaths, accessions to power, conquests, etc., but also major astronomical events.

Stela 8

Situated inside a small shrine, only the lower section has survived. Its dates corresponds to 12 October 652. In front of it are several small square altars.

Stela 3

The structure opposite which this stela stands denotes several construction phases. The small temple at the top, with entrances on all four sides, is the first construction the stela was associated with. Judging from its morphology and size, it must have had a ceremonial function. The final construction phase is represented by the benches at the front, where the stela stands. In front of it are two altars – a circular one from the Classic period and a smaller, square one from the Postclassic. The stela comprises 160 blocks of glyphs arranged in nine columns. The date inscription corresponds to 25 January 633.

Stela 2

This stands opposite Structure 7, which had three construction phases. The first phase is represented by a platform with sloping walls and rounded corners, visible on the rear of the building, which subsequently gained two rooms. The final phase covered the two earlier and constitutes a small adoratorium and altar at the top of the structure. The structure corresponds to the Late Classic but continued to be used as a shrine during the Postclassic. The stela depicts the central personage standing on the back of a prisoner with his hands tied, lying face down – the only one in this position on the stelae that have been found to date. The date inscription on this monument is 4 December 642.

Stela 5

This is situated at the foot of the stairway of Structure 3 and displays carvings on all four sides. The back and front show high-ranking dignitaries, slaves and glyphs, while the sides only have glyphs. The date of the monument is 21 August 662. Opposite stand two altars: a circular one from the Classic period and a square one from the Postclassic.

Stela 6

This is situated inside a small shrine. The date is the oldest one recorded on the stelae at Coba and corresponds to 10 May 613. The occupational sequence covers a long interval of time beginning in the Late Preclassic. The ceramics from this period denote connections with the ceramic traditions of the Peten region and Belize, as well as the northeastern section of the Yucatan Peninsula and Yaxuna. The ceramics from the Early Classic are associated with those of the north-eastern part of the Yucatan Peninsula and the River Belize region. In the Middle Classic, when Coba attained the status of city, the ceramic connections spread to various parts of the Maya area, while the local ceramics derived from the Peten style spread within the region to other coastal sites such as Xelha and Xcaret. The ceramics from the Late Classic show a greater connection to the northern Maya area, giving rise to local variations that set them apart from the ceramics produced in the inland. In the Postclassic, ceramic manufacturing was interrupted or greatly influenced by the style that characterised the ceramics of the north-eastern region, specifically with sites in the west such as Mayapan. The ceramics from the eastern part of the Yucatan Peninsula – greatly abundant on the east coast during this period – are virtually non-existent at Coba, denoting the tenuous connections that existed at the time with other sites in the region.

Maria Jose Con Uribe

From: ‘The Maya: an architectural and landscape guide’, produced jointly by the Junta de Andulacia and the Universidad Autonoma de Mexico, 2010, pp427-433.

1. Coba Group; 2. Group D; 3. Paintings Group; 4. Ball Court; 5. Xaibe; 6. Sacbe 1; 7. Nonoch Mui Group; 8. Macanxoc Group; 9. Chumuc Mui Group.

Getting there:

From Tulum. A combi leaves the corner of Calle Osaris Norte and Av Tulum at 10.00 – possibly not on Sundays. It will drop you off at the entrance to the site at Coba. Cost M$80.

If this is too late a start (which it probably is) then you could try doing the journey in stages with more local combis to the villages along the road to Coba.

Getting information about the return can be problematic. Probably the quickest, if not necessarily the cheapest, is to flag down a collective taxi leaving the village, almost certainly going to Tulum.

GPS:

20d 29’29” N

87d 44’09” W

Entrance:

M$100

Once inside it’s well worth considering whether to hire a bike or not. The buildings are spread out over a wide area and a bike, either powered by yourself or paying for a bike taxi, will save a lot of time. There are hundreds of bikes for rent and tens of bike taxis.

Rent of bike:

M$65 for the length of your stay in the site.