Resistance – Durres

Resistance – Monument to the struggle against Fascist invasion in Durres

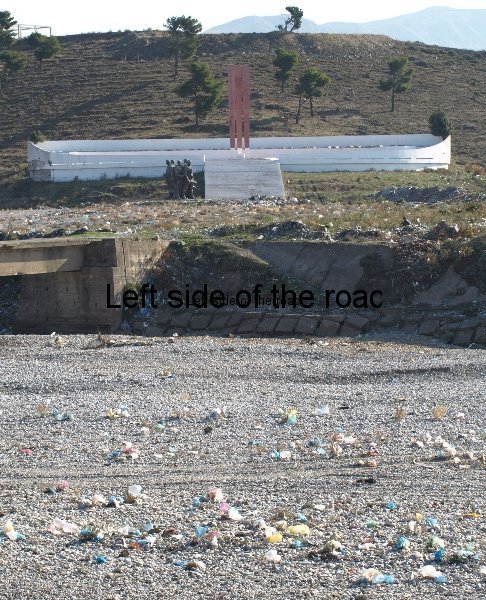

Being the main port of invasion by the Italian Fascists on 7th April 1939 it’s not a surprise that in commemoration of that event, and especially the resistance that was shown by a significant proportion of the population (but not the self-proclaimed ‘King’ Zog who ran away as soon as the Italian ships came into sight) that there are a few monuments to this, constructed in the Socialist period. One is to the individual sacrifice of Mujo Ulqinaku (that used to stand close by the Venetian tower at the bottom end of town) and the other is to the general principle of ‘Resistance’ in Durrës, which is located right next to the waterfront and very likely one of the places the Italian fascists would have landed.

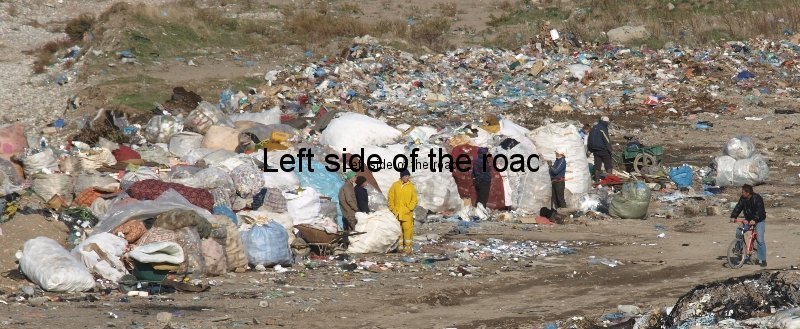

But in 2017 the population of Durrës doesn’t have much respect for Resistance to any foreign invasion. In fact the more foreign goods, foreign fast food and foreign culture they can access the better. In some senses more of a necessity than a wish as they have overseen the wholesale destruction of any industry which might provide them with the basic necessities of life. And, of course, how can anyone possibly survive without the internationally recognised destroyer of teeth and promoter of obesity, the obnoxious fluid sold under the name of Coca Cola?

But back to a time when Albanians had dignity, knew what true independence was and embodied the principles of resistance in their daily lives.

When a monument ceases to have relevance then it no longer gets treated with respect and that has been the fate of this lapidar – as well as with many others throughout the country. Apart from physical damage to some of the elements of the structure it is a constant victim of graffiti attack, the mindless, illiterate scribblings of those with nothing meaningful to say but say it anyway. At least political graffiti would demonstrate some form of human thought.

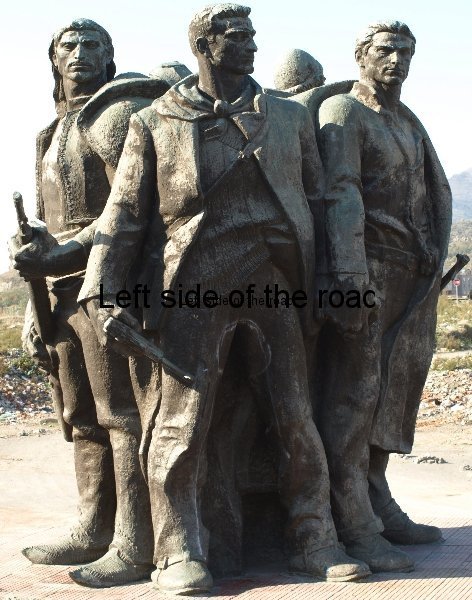

‘Resistance’ has architectural elements as well as sculptural.

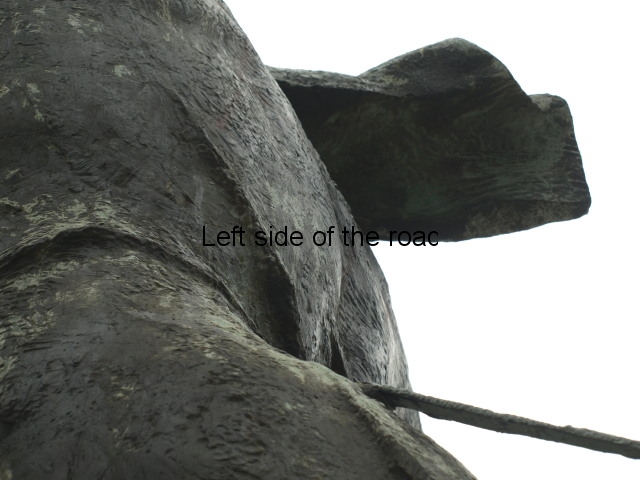

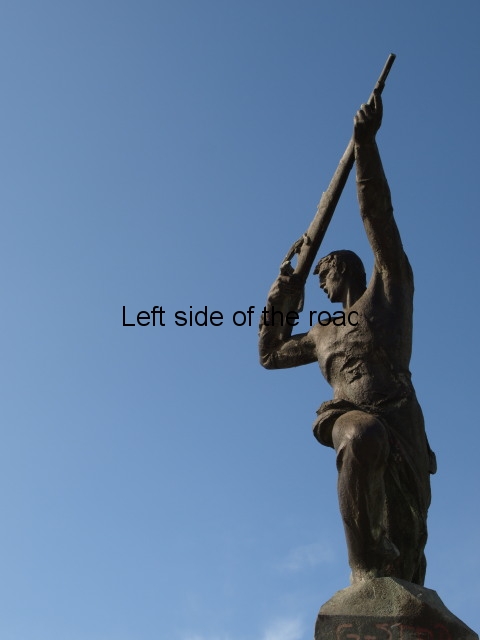

You approach the monument via a few very low, but very wide steps. You are then in a circular space with a series of eleven columns on your right which rise to a height of about 3 metres and on that highest column stands the personification of ‘Resistance’ in the form of a Partisan fighter. Radiating out at 90 degrees to these columns, gradually coming down to ground level even as each of the columns gets higher is a feathering effect. This effect is also produced on the left hand side as you look at the statue but here the feathering is much lower to start with and much wider as well.

If you can imagine the furled wing of a bird you might understand the impression the architect is attempting to re-create. For this is a symbolic reference to the eagle, the double-headed version of which is, and has been for a few centuries now, the national emblem of Albania. This device has been used in the most recent development of the Martyrs’ Cemetery in Borove, just to the south of Ersekë, and for the construction of (the now derelict) mausoleum and museum to Enver Hoxha in Tirana.

The problem with this idea is that it is very difficult to appreciate the idea from ground level. It might well be more evident from an aerial view but that is not possible for the vast majority of onlookers. So in Durrës (as in Borove and Tirana) you have to use a little bit of imagination.

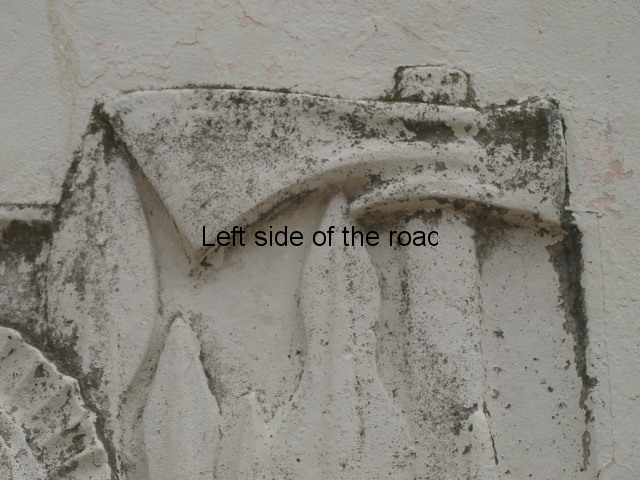

On the facade of four of theses columns, facing the inner circle, are images which tell a little bit of the history of Durrës and Albanian Resistance.

Resistance to the Romans

On the 7th from the right we have the ancient, Greco-Romano history of the town. Carved into the stone is a circular, Roman shield and surrounding it the weapons that would have been used at the time: a short sword, an axe and a number of different types of spears, together with a helmet with a crest.

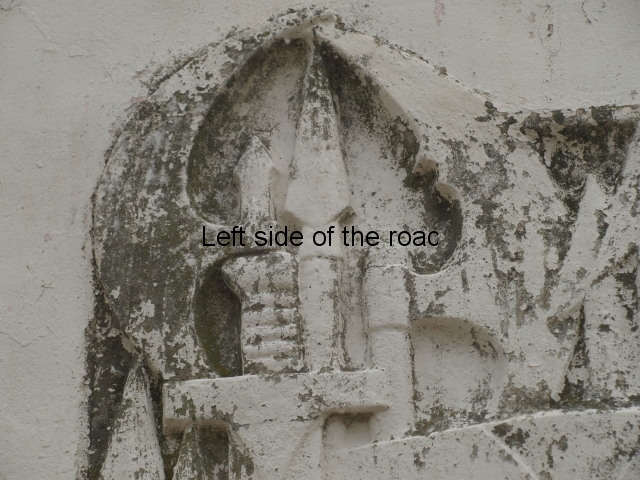

Resistance to the Ottomans

On the 8th one in we are brought a little closer up to date. This is the time of the nationalist ‘hero’ Skenderbeu. We know that as the large shield towards the right has a double-headed eagle design (it was from the time of Skenderbeu that this symbol was adopted as a sign of Resistance to any foreign invader). This was in the 15th century. Here we have the weapons in use in warfare from that period: a long, broadsword, possibly arrows, spears and the curved blade, long poled axe that was used to hack away at the enemy. Examples of these can be seen in the National Historical Museum in Tirana.

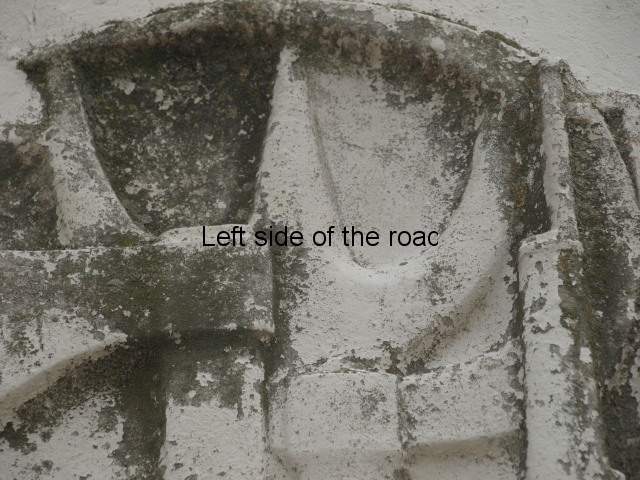

The third lesson in history is on the next column, the ninth and this brings us up to the 20th century. At the bottom there’s a symbolic reference to the waves on the sea. This references Durrës as this image is part of the town’s coat of arms. Curving from the top left to the centre is an ammunition belt – eight clips with five bullets apiece. On the right hand side, taking up the whole height of the panel, is a rifle.

Resistance to Italian Fascism

The top end of the barrels of a couple of rifles peek out from behind the ammunition belt on the left hand side. This modern weaponry frames an axe, a pickaxe and a couple of pitchforks. This, to me covers a couple of inter-related periods. It makes reference to the war for National Liberation (which took place between 1939 and 1944) and also to the construction of Socialism where the use of arms would be necessary to defend the revolution from attack, both from within and without.

The final symbol, which is on the facade of the column upon which the Partisan statue stands, is a large, black metal plaque of a double-headed eagle. Unlike the one on the shield of the Skenderbeu era this one has a star above the two heads. This is the star of Communism which was added to the national symbol from 1944 to 1990. This star, whether it was red originally or not I don’t know, is missing, whether as a result of political vandalism, opportunist souvenir hunting or by someone to care for it so that it can be returned in a future Socialist Albania.

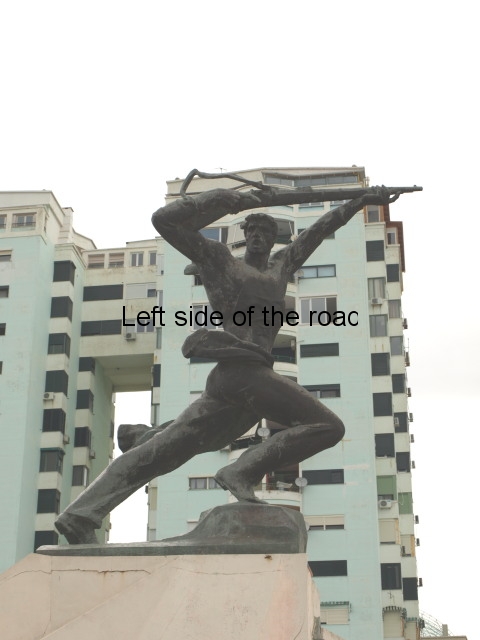

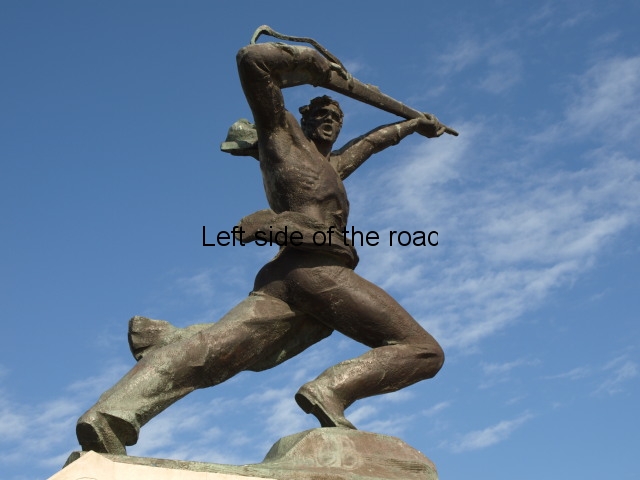

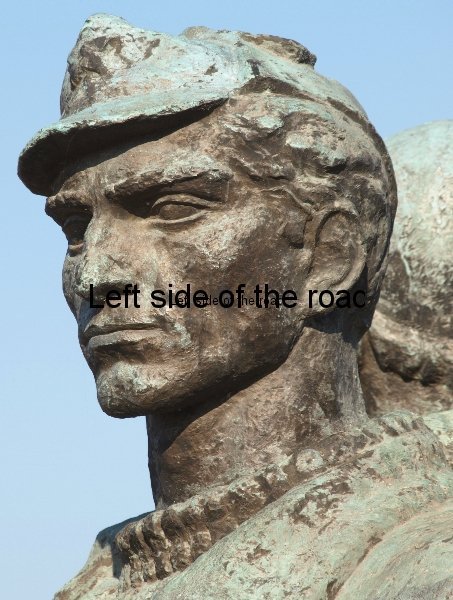

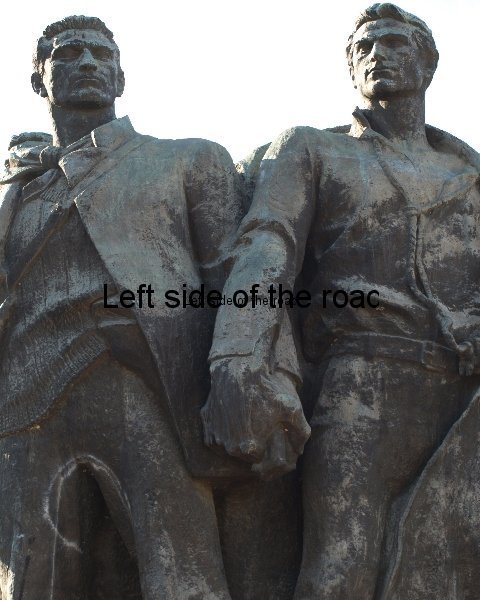

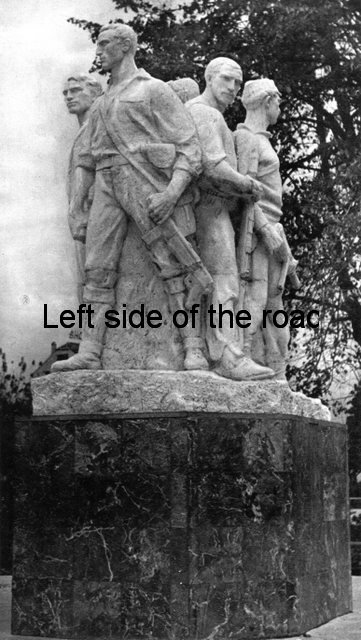

The statue itself embodies many of the attributes seen on a number of lapidars throughout the country. The figure itself is rushing forward, weapon at the ready, but he is also looking backwards calling upon others, out of sight to come and join the fight. This is depicted elsewhere on Albanian lapidars such as the monumental Arch of Drashovicë and the statue of Mujo Ulqinaku in Durrës itself – but exact location unknown at this moment.

But there’s much more dynamism, more urgency here. He cannot stretch his legs any further, he gives the impression of needing to rush to the front, to engage the enemy. When there’s an invasion there’s no time to consider the options. Only those who are prepared to live under a foreign yoke, the future collaborators, the sycophants and cowards, will hesitate, ‘weigh up the options’ and then capitulate. This fighter, this Communist, this patriot does not hesitate.

He doesn’t wear a uniform as such as at the time of the Italian invasion in 1939 the so-called Royal Albanian Army was so much in a collaborative role with the Italians that official resistance melted away. It was up to a few individual soldiers, such as Mujo Ulqinaku, or armed civilians to resist the invasion. Although they were far too outnumbered in 1939 to succeed in preventing the country from being occupied the action of workers such as those at the tobacco factory and the growing number of those who joined the Partisans in the subsequent five years meant that the country was finally liberated at the end of November 1944.

He’s bare-chested and it looks like his shirt has been torn off his body and it hangs in shreds, flowing behind him as he rushes forwards. In general there’s nothing to distinguish him from any other national hero, racing to take on the enemy but there’s one little, unique indication that this is an Albanian patriot.

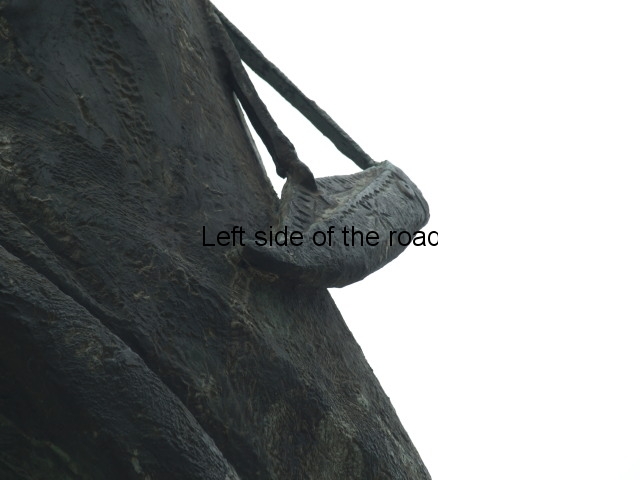

‘Opinga’ bag

Hanging from a thin leather strap, that goes around his neck and rests against his left thigh, is a small bag. It looks very much like an opinga (the traditional leather shoe) with decoration on its facing and edges. I’ve not seen this elsewhere and can only think that when modern dress became more common, especially in a city like Durrës where more people would have been involved in manufacturing industry or dock related activities, these reminders and remainders of the past would have taken on a secondary role.

The official name of the monument is:

“Monumenti i Rezistencës.”

Which translates as:

‘Resistance Monument.’

Which was ‘dedicated to the armed struggle of the Albanian people against the fascist occupation of Italy on April 7, 1939.’

This lapidar is the combined work of Hektor Dule and Fuat Dushku (1930-2002) but I don’t know which of them (if either) was the originator of the architectural aspect of the monument. Dule also created the Mushqete Monument at Berzhite and the bas-relief to Skenderbeu in Gjirokaster. Dushku was one of the sculptors who worked on the ‘Four Heroines of Mirdita’ that was created in 1971 and used to stand in Rrëshen. That was criminally destroyed by the local reactionary so-called ‘democrats’.

Signatures

This is quite a late lapidar as, according to the inscription under the right foot of the fighter, the statue was created in 1989. This inscription is also quite unusual. It has the names of the two sculptors, H[ector] Dule and F[uat] Dushku and then the letters QRVA followed by the number 89 (for the year 1989). QVRA stands for Qendra e Realizimit te Veprave te Artit, translating to Art Work Realization Centre. This is the name of the (State) foundry in Tirana where virtually all the lapidars in the country, from the late 60s to the end of the 80s, were forged. It’s also the place where many of those that were torn down in the 90s were melted down to construct some of the monstrosities that is contemporary, capitalist Albanian sculpture. This foundry at one time employed 40 people, more or less, full time. That went down to just 5 a few years ago and then was torn down to make way for expensive, luxury flats.

This is the first time I’ve seen these initials on a lapidar (but not the last, the large statue of the Partisan and child in Lushnjë Martyrs’ Cemetery and the bas relief outside the vandalised museum in Bajram Curri being two other, late Socialist period examples). In the post on Liri Gero and the 68 Girls of Fier I made a bit of a digression discussing the idea of the artists NOT putting their names on their work. This did not mean that their work was not appreciated or respected but the artist was only one cog in the machine. The finished work of art was the culmination of the work of many and if one name should be on it why not all the others?

It was only when that principle was being challenged, especially after the death of Enver Hoxha in 1985, that the sculptors’ names started to appear on the finished work. And here, in addition, we have the place it was made. This no more or less than branding. If they had been able to continue making such statues they would have been stamping the © (copyright) sign on the base.

They didn’t realise that the more they adopted capitalist methods the shorter would be their future. Such foundries, workshops only exist in the capitalist countries with the patronage of the rich – just as it was in the Renaissance. There aren’t many of those in Albania and so the foundry died. I don’t have much sympathy for those with such myopia – whether they be foundry workers or sculptors.

Condition:

As can be seen from the pictures the plinth and the surrounds are uncared for and there’s various graffiti on the columns. The columns provide steps for children to climb and they often do. However, the statue itself seems to be untouched by the vandalism and is in a good condition.

Location:

In the park beside the water, in the older part of town, beside Rruga Taulantia, and a hundred metres or so west of the Venetian Tower (and the original location of the monument to Mujo Qlqinaku).

GPS:

N41.30936204

E19.44467501

DMS:

N41º 18′ 33.70”

E19º 26′ 40.83”

Altitude:

1.7m