Chairman Mao and Enver Hoxha

More on Albania ….

The definitive split between Albania and China, 1978

In July 1978 the Party of Labour of Albania published (in an open and public forum, that is, as a supplement to the July/August, No 4, edition of Albania Today) a letter which the Party had sent to the Central Committee of the Communist Party of China. This letter was promoted by the sudden – though not totally unexpected – move of the Chinese to remove all support, materially, financially as well as personnel, from Albania, a country which, up to that time, had held the closest fraternal links with the much bigger Party, country and people.

Not only did the publication of this letter spell the end of the special relationship between the two Parties it also prompted a split in various Marxist-Leninist parties throughout the world with groups taking ‘sides’ in the argument. At times the argument became bitter with both sides forgetting the principle of comradely debate over issues before becoming entrenched in an irreversible stance.

If the International Communist Movement was too slow in denouncing the Soviet Revisionists in the 1960s it was too fast in coming to a decision in the late 1970s.

This (late) contribution to the debate is written in the form of a letter to those who might hold the (mistaken) belief that all was running smoothly and in perfect harmony with the tenets of Marxism-Leninism in China before the death of Mao in September 1976.

Less than two years after Mao’s death the revisionists and ‘capitalist roaders’ were in firm control of the People’s Republic of China and were already dismantling many of the achievements made by the Chinese people since the Declaration of People’s Republic on 1st October 1949.

The counter-revolution doesn’t come from nowhere. Revisionism within a Communist Party does not come from nowhere. Marx, Engels, Lenin, Stalin, Mao and Hoxha all knew that the poison of revisionism was an integral part of all communist parties. They wrote hundreds of thousands of words on the topic; fought against the individuals peddling defeatism and an anti-proletarian ideology; warned of the consequences of a lack of vigilance; instigated ‘cultural revolutions’ in an effort to prevent such ideas getting a hold in Communist Parties; purged parties of those who were identified as promoting such counter-revolutionary views; yet it was still able to get a stranglehold on parties throughout the world – in fact no party was free of the disease.

Matters moved quickly in China and it wasn’t long before the pro-Chinese stance became untenable – the restoration of capitalism was obvious to all. But the pro-Albanian side had to look to its arguments when the country started to lose grip on the revolution after the death of Hoxha in 1984 and then everything hit the fan in 1990.

In a sense I believe those who were so upset that the Chinese Party (and Mao as well) was being heavily criticised by the letter of the PLA of July 1978 fell into a similar trap that many in the pro-Soviet camp found themselves in the 1960s – failing to accept that even the most revolutionary parties can get it wrong and refusing to look at matters and events in an empirical, Marxist-Leninist manner.

This post is a minor contribution to the debate. If I’ve got it wrong let me know.

‘Communists must always go into the whys and wherefores of anything, use their own heads and carefully think over whether or not it corresponds to reality and is really well founded; on no account should they follow blindly and encourage slavishness.’

(‘Rectify the Party’s Style of Work’, (February 1st, 1942) Mao Tse-tung Selected Works, Vol III, p 49)

Comrades

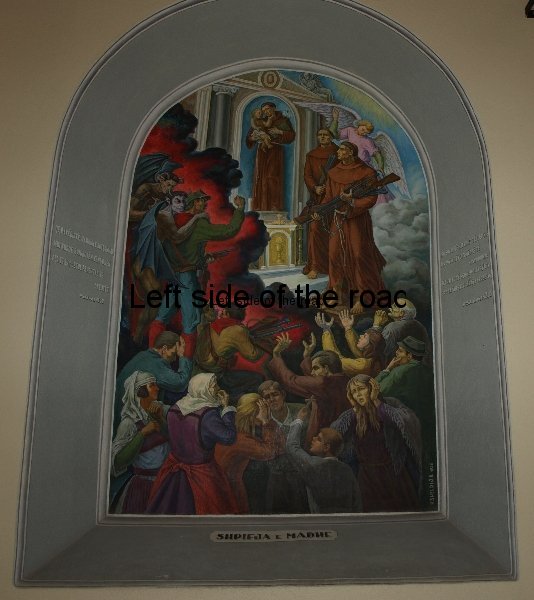

I never thought (especially in the 1970s) there was any contradiction in supporting both Albania and China and their respective Communist Parties and leaders. To this day both the Chairman and Enver are celebrated on my walls as outstanding leaders of the Marxist-Leninist movement and true heroes of the working class.

If the debate between the Maoists and Hoxhists raged in any sense in Britain I was not part of it. From 1986 onwards I started to spend more and more time out of the country and was more concerned with understanding the society I was in at the time rather than what, on occasion, seemed like esoteric and pointless arguments of the relative merits of the two, now dead, leaders. Also I was no longer a member of a ML party as I had disagreements with the Party I had been a member of for 12 years on changes in its policies toward the British Labour Party nationally and the approach towards Soviet Union internationally – a break that took place after this was enshrined in the Party’s Congress document in 1982.

My time in Zimbabwe in 1986-7 meant I was trying to understand how that society had changed since the declaration of ‘independence’ in 1980. Yes it wasn’t a truly socialist revolution I would have wanted, nor what some people I met there wanted as well. But at least it was a move forward from the racist Smith Regime and, I thought then and still think now, there was a potential with Mugabe. The fact that it hasn’t been achieved is complex and too complicated to go into here. The reason I mention it is that I was literally half a world away when some of the disagreements between the two groupings started to get more entrenched – although the exact chronology of that particular polemic is unknown to me.

When everything hit the fan in 1990 and riots on the streets of Albania led to the toppling of Enver’s statue in the centre of Tirana I was in the Andes of Peru, attempting to improve my Spanish as well as understanding more of the struggle of the Communist Party of Peru – Sendero Luminoso. I was so immersed in those activities that I wasn’t truly aware of what was happening in Europe. The socialist development there was going through a crisis and I was in a country where it looked as if – at least in 1990-1 – that success could well be on the horizon. The fact that the struggle collapsed there is something which should be studied (as I don’t think it has, partisan views with individuals and groups holding their own corner making any objective study of the disasters that occurred in Peru being analysed in a dispassionate manner an impossibility).

Whilst not being part of the debate (between Maoists and Hoxhists) I didn’t think it was all entirely pointless. However, I did consider that it should have taken place in the manner that Mao talked about debates and disagreements taking place among the people in a Socialist society – i.e., in an non-antagonistic manner. Unfortunately, for reasons I don’t really understand, many decided to throw accusations at the opposing side and then ideas became entrenched. Such a climate is not one Marxist-Leninists should tolerate as it gets us nowhere.

I have read the letter of the CC of the PLA to the CC of the CPC a number of times and I have a much more positive attitude to what it contains than would be the case for those who still maintain the ‘Maoist’ approach of the 1970s. Not only positive in the sense that it introduces some important ideas about relationships between fraternal parties but also in that it brings to light matters which are some times forgotten (or brushed over) from the ‘other side’.

The fact that the three socialist societies involved no longer exist as workers’ states cannot be ignored. That very fact means that mistakes have been made, mistakes of such gravity that what many of us held up to be the future for the workers in out respective countries was attacked, or at least allowed such advances to be taken off them, by the very workers themselves in those states.

Mao, in the pamphlet ‘On the question of Stalin’, stated that Uncle Joe was 80% correct in what he did as leader of the Soviet Union. I always thought it difficult to quantify such achievements in that manner but if it is possible to do so for one individual what sort of result would we get if we applied the same reasoning to both Mao and Enver? However, I don’t think that such an approach really helps us understand the errors of the past so that they are not made in the future.

I also have difficulties in placing such a responsibility on individuals in the first place. If Joe, Mao or Enver were responsible for the defeat of the revolution and the victory of, first, revisionism and then outright capitalist restoration, where were the rest of the Party? What did the workers and peasants of those countries think and do? Don’t they have to take some responsibility? Why are all people victims?

If I stated the success of the October Revolution was solely down to Lenin and Stalin I would be rightly criticised for ignoring the role of the workers and peasants in that momentous occasion. Likewise following the wars of liberation in both China and Albania. Yes, such leaders are crucial for those successes but leaders without followers prepared to go into the unknown are nothing.

Hindsight is a wonderful thing but one of the merits of the letter from the CC of the PLA is that it DID foresee what was likely to happen in China if it continued along the path it started to take after the death of Mao. However, by analysing some of the points the letter raises we can see that the seeds of the rot were sown some years before Mao’s death.

The main reason for the letter was the unilateral removal of economic and military support that China had provided to Albania, in increasing levels, after the removal of virtually all similar support by the Soviet Union in April 1961. So a small socialist country, surrounded by enemies of both the revisionist and imperialist variety, was being weakened by a previously fraternal country which had declared that it was also was in opposition to such reactionary forces.

So the anger and frustration that is obvious throughout the document is fully understandable and accounts for the manner in which Albania brings up other disagreements which had previously been kept secret, which, in themselves don’t amount to irreconcilable differences, but when taken together show a dangerous and disturbing trend.

In the UK ‘the size of Wales’ is often used to describe the smallness and, often, insignificance of a particular part of the world. Albania is almost exactly the size of Wales in land mass, geographical features and (in 1990) population. Albania, however, had strengths which Wales never had or will have (unless the situation changes radically) and that was its liberation war led by a Marxist-Leninist Party and the attempts to construct socialism in a hostile world. Albania also had (and still has) an abundance of natural resources. Therefore a fertile climate for the construction of socialism – a revolutionary leadership with a clear ideology and a politically conscious population having the possibility of being able to exploit the country’s resources for the benefit of the whole population. But it needed help from fraternal countries, it needed those skills which they had not yet had time to develop internally, they needed time to learn how to stand completely on their own feet.

Perhaps we should remind ourselves of the situation which Albania found itself in November 1944 when they succeeded in defeating, without the aid of any other external army, first the Italian and then the German Fascist occupiers. Tens of thousands of Albanians had died, either through combat in the Partisan army or by the policies of the invaders which punished the civilian population for the successes of those Partisan forces.

Albania didn’t suffer the level of infrastructure damage as other European countries did between 1939 and 1945, mainly as there was little infrastructure to be damaged. The collaborationist governments prior to the invasion of the Italians in April 1939 had used the country more as a fiefdom and didn’t have a concept of development that didn’t have a direct effect on their own desires. And the population at the time of liberation in November 1944 was only hovering around the one million mark.

No sooner had the war against Fascism in Europe come to an end when the imperialists started their war against any attempts to spread Communist ideas in those parts of the continent not already under the influence of the Soviet Union and the Red Army. (The question of the construction of Socialism in countries that did not liberate themselves and with an unproven Communist, Marxist-Leninist leadership is yet another one that needs to be analysed but, again, here is neither the time nor the place.)

The Greek Civil War started in 1946 and at exactly the same time the British imperialist navy made threatening manoeuvres in the narrow channel between the Albanian mainland and the Greek island of Corfu. This so-called ‘Corfu Channel Incident’ led to damage to a couple of British warships and the death of around 50 British seamen. The US/UK alliance was able to sway the United Nations and one of the upshots of this was the sequestration of Albania’s gold reserves, denied the official and legitimate government of Albania until the start of anarchy in 1991. Military threat hadn’t achieved the backing down of the country so economic measures, achieved through diplomatic machinations, were brought into the mix.

At almost the same time the erstwhile ally against Fascism, Yugoslavia, with Tito at the head, made territorial claims against Albanian arguing that such a small and economically weak country wasn’t viable, going against any ideas in Marxism-Leninism of national independence. The refusal of the Communist Party of the Soviet Union (CPSU), still a revolutionary Party at that time, to accept this blatant attempt at a ‘Greater’ Yugoslavia led to the country being expelled from the Cominform (Communist Information Bureau, the successor to the Comintern – the Communist International) in 1948 and the inexorable move of that country away from Socialism and into the waiting and willing arms of capitalism and imperialism.

Due to Albania’s stance against this first wave of post-WWII revisionism, that of Tito in Yugoslavia, the country had a firm friend in Stalin and the Soviet Union. This meant aid coming from the severely war damaged revolutionary ally but the ‘easy’ years were few as Hoxha would have been very suspicious of the way the CPSU was going after Khrushchev’s ‘secret’ speech at the 20th Congress in 1956.

However, in the 17 years or so of receiving Soviet aid Albania was able to use the opportunities offered to educate and train their own specialists and experts to be able to start the building of the infrastructure needed for the independent development of a socialist state. Although this all came to an abrupt end in the early part of 1961 the Albanian leadership would not have been entirely surprised.

Since Khrushchev’s denunciation of Stalin in 1956 the Party of Labour of Albania (PLA) had been continually critical, in private, following the norm of disagreements within the International Communist Movement, but came out in a very public manner in 1960, first at the Bucharest Conference of the World Communist and Workers’ Parties in June and more especially at the meeting in Moscow of the 81 Communist and Workers’ Parties in November of that year.

It was at this meeting, in the capital of the world’s first Socialist state that Hoxha tore into the sham Marxist justification that the Soviet Revisionists had been peddling since 1956. Already before this meeting statements made by the Soviet party were becoming more personal and unprincipled, treating the Albanian Party and people as insignificant in the scheme of things solely dependent upon land mass and population. This arrogance of the larger and more established party was challenged at every opportunity, with Hoxha taking the principled stand at all times. But such a stand would have, and did have, its consequences.

It’s no wonder that, in July 1978, the Albania Party would have feelings of anger, frustration, and a sense of betrayal (almost of deja vu) when they had to face the same sort of disruption to their economic and social plans with the unilateral withdrawal of Chinese experts. It must be remembered that in a society where development is in a planned manner (normally a series of Five-year Plans) such foreign aid would have been factored into any plan and its abrupt withdrawal would have a knock-on effect on other projects.

But the situation with the break with China was different to that 17 years earlier with the Soviet Union. The internal debate about the way forward for the International Communist Movement was an internal affair for many years (I tend to think, in hindsight, too many years). Matters only came out in the formal, public arena in the early sixties. Up to 1978 ALL the differences and disagreements that the PLA had with the CPC were kept within contacts on a Party to Party basis. The only time that many people in Communist Parties throughout the world would have been aware of the extent or the seriousness of the dispute between the two parties was on the publication of this letter. This situation, I believe, accounts for the litany of disagreements that followed the statement of the effects and possible consequences of the ending of Chinese aid.

The PLA, and I agree with their assessment on this matter, did everything that was expected of a fraternal Party and yet, this time very much out of the blue, the Chinese experts were pulled out with instructions to take any blue prints and paperwork with them – or to destroy such material if that was easier.

It’s also important to make reference to the fact that it wasn’t just economic aid that was withdrawn. Albania wanted to have an independent military policy, not depending upon others to ‘defend’ them from any revisionist or imperialist aggression in the future (taking into account the events of July 1978 such an approach was shown to be crucial). But in the very act of withdrawing military aid the Chinese made public where they were aiding Albania and thereby betraying any secrets that the country might have had in this field.

What was even more telling is that China did to Albania exactly what the Soviets had done to them (the Chinese) in 1960, that is, withdrawing technicians involved in friendship projects. Being a bigger country China was more able to deal with such an abrupt interruption in major infrastructure projects. The effects were much greater in Albania in 1978 as at that time projects which were vital for the future development of the country were effected, notably the hydro-electric projects which revolved around Lake Koman in the north-east of the country.

That might seem like I’ve spent a lot of time going over the history of PLA/CPC relations but without an understanding of what happened before the serious (and, ultimately, irretrievable) break in 1978 there’s no understanding of why the PLA wrote what it did, and the reasons for their arguments.

What constitutes the eleven separate clauses of the second section of the letter is a list of occasions where relationships between the two parties were strained, to say the least. This is supporting an argument, if you like the basic thesis of the letter, that what the CPC did in July 1978 wasn’t a radical change in direction, just the confirmation of what had been developing over a period of 15/16 years, ever since the revisionism of the CPSU was out in the open and other Communist and Workers’ Parties throughout the world were aligning themselves on one side of the polemic or the other.

In a sense their emphasis was on what had happened in the past, of those matters that had caused concern to the Albanian Party and how they led to the 1978 present. For that reason I don’t think we should see their omission to comment on what had happened in the previous two years, in China, since the death of the Chairman, to be other than an issue that was not pertinent to the argument at the time.

1.

To me there are two points in this first section. The first point is that the CPSU, through the statements of Khrushchev, was adopting the ‘mother party’ principal which meant that all other parties, whether in power or otherwise, should bow down to the decisions and dictates of Moscow. This issue had long existed in the international movement, especially before the end of World War Two, when the only Socialist country in the world was the Soviet Union. There was definitely a reason to have respect for a proletariat that was actively working to build socialism, after all they were in the process of having a hands on approach to building socialism, in other countries it was still a theoretical concept.

But even the Communist movement is not immune to prima donas who want to be big fish in little ponds and don’t understand their (insignificant) position in the greater movement. And that’s not just a thing of the past – we’ve had a number of examples where such an approach has led to disaster in a number of countries since the ‘fall of Communism’ in the 1990s. We can also get an historic idea of this problem from the necessity that caused Lenin to publish ‘Left Wing Communism – an Infantile Disorder’ in 1920.

However, after the success of the Albanians in their War of Liberation at the end of 1944 and the declaration of the Peoples’ Republic of China by Mao in October 1949 the unique nature of the Soviet Union was no longer tenable. Stalin didn’t push this line in the eight years he was alive after the Great Patriotic War, it was only with the victory of revisionism in the CPSU that Khrushchev considered he had the ‘right’ to assert this dominance. He had got away with denouncing Stalin – and all he stood for – at the 20th Congress of the CPSU in 1956 and became emboldened in his approach. (In his arrogance Khrushchev denigrated Albania by making statements such as ‘the mice in the Soviet Union eat more grain that the population of Albania need to survive’. This was an early demonstration of the Great Power Chauvinism of the Soviet Revisionists.)

Secondly, there was the reluctance of the CPC to openly, and firmly, confront the revisionists in the two major public fora in 1960, first at Bucharest and then in Moscow. The CPC rejected the ‘rehabilitation’ of Tito and the Yugoslav revisionists – something which the Albanians were vehemently against due to the reasons already stated above – but their approach was considered lacking in enthusiasm, to say the least, by the Albanians.

The CPC didn’t even seem to be willing to defend itself. Although he was getting a lot of stick from Albania Khrushchev knew that if he directed his venom against such a small (but vociferous) member of the community of Socialist nations he would be considered by many to be a bully. He, therefore, directed his attacks against the country which comprised a quarter of the world’s population at the time, the People’s Republic of China. Why was Chou En-lai reluctant to engage in ‘polemics’ at that time? Why did he want to keep matters quiet? What was wrong with having a principled debate? Remember that this is now more than seven years after the death of Stalin and 4 years since the vicious attack on Marxism-Leninism in Khrushchev’s so-called ‘secret speech’.

It was only when I was going through the issues of Peking Reviews of the first years of the 1960s that I was reminded of how long after the crucial Moscow Meeting, in November of 1960, that the Chinese Party still seemed to hold out hope that the Soviet Party could be diverted off its road of downright betrayal of Marxist-Leninist principles.

Some might argue that the Chinese were just working through the established processes between Communist Parties and they were looking for a way to avoid a clear split in the international movement.

I cannot agree with this procrastination. How much more proof did the movement need in the early 1960s that the Soviet Union was no longer following the road of Lenin and Stalin? It was not only that all the achievements of the Soviet workers and peasants in the building of their economy (through the collectivisation of agriculture and the vast increase in the industrial potential of the country) – as well as the defeat of Nazism – had been trashed in Khrushchev’s speech at the 20th Congress in 1956. He also undermined the leading role the Soviet Union had established in the world as an example to the rising national liberation movements. This was to cause confusion in those movements and allow for imperialism to crush revolutionary movements (a tragic example being Lumumba in the Congo), their confidence growing as they saw a divided Communist movement. China might have wanted to keep matters ‘quiet’ but capitalism and imperialism knew exactly what was going on. So from who were the Chinese wanting to keep the disagreements secret?

2

Events of June 1962, when the Albanians had unsuccessful and acrimonious meetings with both Liu Shao-chi and Teng Hsiao-ping, in hindsight seem to have a greater importance looking back from the present than they even did at the time (or even in 1978 when the letter under discussion was published in ‘Albania Today’). The Chinese Party seemed to be obsessed with establishing an alliance against US imperialism with anyone – notwithstanding that revolutionary principles would be discarded in the process.

The CPC seemed to be oblivious to the changes that had taken place in the Soviet Union which meant that it was becoming a rival to the US not in that it represented and championed a different social system, a different reality for the workers and peasants, but was rapidly becoming another imperialist player in the ever-changing capitalist system.

What were the Chinese proposing then that was in any way fundamentally different from the erroneous and totally unprincipled so-called ‘Theory of the Three Worlds’ that was resurrected just before Chairman Mao’s death in September of 1976? By the 1970s there were a few more players in the ‘first world’, including the Soviet Union (now branded as ‘social-imperialist), but it meant making alliances with any number of fascist regimes in the process.

Maoists throughout the world rejected this ‘theory’ when it was pushed by the Chinese Party in the 1970s. Why wouldn’t they also reject something similar when proposed 14 years earlier? What was wrong with the Albanian stance in the 1960s that was substantially different in the mid-70s? Alliances yes, but they have to be based upon certain principles or, in extreme circumstances (such as 1939 in Europe with the Non Aggression Pact between the Soviet Union and Hitlerite Germany) based upon the best that can be achieved at a particular time, with no illusions and with the understanding that such an agreement is unlikely to last for long.

If nothing else the actors involved in 1962 should start to ring alarm bells. This was just one of the first occasions when Liu showed his true colours and it’s no surprise his principle henchman was also peddling such poison. Teng’s rehabilitation, when Mao was still alive, and the subsequent destruction he was able to reap on Socialism, the Chinese Party and people in the latter years of the 20th century was being signposted many years before.

I agree that it is far too easy to rely on hindsight, my point here is that even in 1962 the Albanians were on the ball when it came to a revisionist development within the Chinese Party – a development that wasn’t stamped upon even during the thought-provoking days of the Great Socialist Cultural Revolution, when many of the ideas of these two ‘capitalist-roaders’ were being challenged in open debate, nationwide.

In the document it suggests that it was only after August 1963, when a test ban treaty was signed between the Soviet Union, the USA and the UK, that China realised it hadn’t succeeded in establishing the close relationship with the Soviet Union that it had wished and hence this was the start of what became known as the ‘International Polemic’. I’m not sure if anyone ever put an exact date on that important period in the history of the World Communist Movement but even if it is that’s still just under three years since the Moscow meeting. Three wasted years, I would suggest, and three years in which the revisionists throughout the world had a freer hand to sow their poison in their respective parties. We cannot forget that whilst all this manoeuvring was going on revisionism was establishing a greater grip on many Communist Parties. The refusal of the CPC to acknowledge the irreversible split with the CPSU helped only revisionism, reaction and imperialism.

3

In the summer of 1964 the Chinese began a dispute over border issues on the Ussuri River in Siberia. Why?

I would add a number of points not stressed by the Albanians in this letter. The first is that one of the first actions of the Bolshevik government when it had gained power after the 1917 October Revolution was to repudiate all and any treaties which it considered to be part of Tsarist expansionism – the disputed area in 1964, as far as my memory is concerned, was one of those places where the new Soviet state gave back land to a then capitalist China. Even if the Chinese still thought they had been hard done by following the Leninist approach to land boundaries why did it take them 15 years after the declaration of the People’s Republic in October 1949 to raise the issue? Why did it have to be such an antagonistic conflict, with ordinary soldiers on both sides being killed or injured? Why did it take place when the issue of ideology was of much greater importance and significance? And, perhaps not understood in the same way then (at least by me), why didn’t the Chinese Party realise that Khrushchev would have been able to tap into the deep nationalistic feeling that permeated all of Soviet (and now Russian) society?

This latter was never mentioned, as far as I know, in the late 1960s but we have seen in recent years how the capitalists in present day Russia have been able to tap into, for their own ends, the feeling of pride that exists within Russia in their victory over the Hitlerite Fascists in the Great Patriotic War. That feeling was as strong in the 1960s as it is now and would have allowed Khrushchev, internally, to have turned the issue into yet another aggressive, foreign state wanting to threaten the integrity of the Soviet Socialist Homeland. This allowed him to divert attention from the real political issues that were being fought out, issues that were clear in 1942 and which led to the victory of the glorious, socialist and revolutionary Red Army.

Such an unnecessary conflict was not in the interests of anyone but the revisionists. If the whole matter was at the instigation of the Soviets why did China respond in such a hostile manner? It’s in Siberia for Christ’s sake! If the Soviet revisionists had planned to tempt the Chinese to react so they could make a meal of it in their propaganda internally then the Chinese did exactly what they shouldn’t have done.

In passing it’s perhaps worth mentioning the later, similar conflict, which the then revisionist Chinese Communist Party instigated against Vietnam in 1979.

4

It was before my time being involved in Marxist-Leninist politics so I wasn’t aware that once Khrushchev was thrown out in October 1964 there were renewed attempts by the CPC to re-establish good relationships with the CPSU under the leadership of Brezhnev. Why did they do that? What did they think had changed with a different leader in position? Hadn’t the revisionists entrenched themselves in all levels of the Party in the more than eleven years since the death of Stalin?

I find it difficult to see what the CPC was hoping to gain. Things had been said and done which had created a situation where it was impossible to go back to a situation pre-20th Congress. And this is not even starting to address the changes that had taken place in many Communist parties throughout the world or even taking into account the events in Hungary in 1956, the construction of the Berlin Wall in 1961, the so-called ‘Cuban Missile Crisis in 1962 and the escalation of the war of intervention in Vietnam, all events that had changed the dynamic of the International Communist Movement. With the movement in a state of flux it was not totally capable of making the most of the opportunities presented or being able to deal with the problems that arose as a consequence.

I don’t understand why Chou En-lai was so struck on the idea that the change in leadership would necessarily lead to a change in approach. He doesn’t seem to have shown any understanding of the history of the Communist movement, from its earliest of days, and the constant threat that was revisionism. He also, in his dealings with Albania, seemed to forget that the PLA and its leadership were ‘persona non grata’ in Moscow after Hoxha’s speech at the November 1960 meeting and that there were no diplomatic, let alone fraternal, relationships between the PLA and the CPSU so there was no way that a delegation from the PLA would ever get near to any celebration of the October Revolution (taking place in Moscow on 7th November 1964).

(As an aside here I’m unsure of the relationship that the PLA had with Chou En-lai. He was often the ‘bad guy’ when it came to a conflict between the PLA and the CPC in the 60s and 70s. His presence or involvement in such meetings is not a surprise as his remit was foreign affairs. However, in January 1976, just after his death, Enver Hoxha (as well as many of the top leaders of the PLA) visited the Chinese Embassy in Tirana to express their condolences. There was an official mourning period in Albania and this was all publicised in their foreign language press.

On the other hand when Chairman Mao died in September 1976 the response in Albania was definitely cool. This is despite the fact that there was a major supplement in ‘Albania Today’ on the occasion of Mao’s 80th anniversary in 1973 and articles in the Albanian press praising Mao and Albanian-Chinese friendship as late as 1976. The last mention in ‘Albania Today’ which could be seen as one of fraternal friendship between the two countries and parties was a short article in issue No 1 of 1977 entitled ‘The name and work of Comrade Mao Tse-tung are immortal’, reprinted from Zëri i Popullit of 26th December 1976, on what would have been Chairman Mao’s 83rd anniversary. Despite this there’s definitely a feeling that matters changed between the two parties in the weeks prior to Chairman Mao’s death.)

5

If there’s one area in the letter from the PLA where there is a reference to contemporary events

(that is, in 1978) it’s in the ideas presented in No 5, where, it seems, the Chinese revisionists (already in control of the CPC less than two years after the Chairman’s death) asked that the Albanians repudiate the whole process that was the Great Socialist Cultural Revolution.

There’s no surprise that the request was made. Those in control of the CPC needed to get as many people as possible to forget the Cultural Revolution as it was here that all the ideas and theories that they were starting to peddle in the post-Mao era had been attacked and challenged. Even whilst not agreeing to this demand of the Chinese revisionists the letter makes comments where it suggests that the PLA was not totally in agreement with some of the methods and practices that characterised the Cultural Revolution. However, they were clear that there were reactionary elements within the CPC that had gotten into positions of power and were threatening the very existence of the Chinese construction of Socialism. The PLA had had direct experience of this revisionist trend in the CPC with their meetings with Liu Shao-chi and Teng Hsiao-ping way back in June of 1962 (see above).

I think that the PLA’s arguments here are quite honourable. They had been asked by Chairman Mao to come out in public support for the Cultural Revolution as he (Mao) believed there was a very real threat to the Chinese Revolution. Although there had been ‘cultural revolutions’ (small ones and not to the same extent as in China between 1966 and 1976) in the Soviet Union what was unleashed in China was of a qualitatively – as well as a quantitatively – different nature. It has become one aspect of what defines the uniqueness and progressive nature of Maoism.

However, Hoxha and the PLA had some reservations about the methodology. I don’t think that’s a problem. Revolutions by their very nature are unpredictable. In fact a ‘predictable’ revolution is, by definition, not a revolution. History showed that way back in the 18th century in France. A revolution can devour its own as well as its enemies. The French Revolution was a minor affair when compared to the extent of the Chinese Cultural Revolution in both its extent geographically and the vast numbers of people involved. Mistakes would have been made and there’s nothing wrong in saying so.

We now know, with the publication a year later (in 1979) of Hoxha’s ‘Reflections on China’ that he, privately up to that date, had more serious and deeper differences with the CPC – but that was kept secret, in the way that fraternal parties should discuss differences, until after an irreversible break had taken place between those two parties. And it cannot be denied that the road taken so soon after Mao’s death with the coup within the Chinese Party had already, by July 1978, demonstrated that the revisionists and ‘capitalist-roaders’ had seized power in Peking. We now know clearly where that was to lead.

I do disagree with what is stated in the very last paragraph relating to item 5. This is where the PLA seems to bemoan the fact that there had not been any real analysis of the positive and negative aspects of the Cultural Revolution by the, then, present leadership of the Party. This seems to indicate a certain naiveté on the part of the PLA as for the leadership in control from the end of 1976 to the present day see EVERYTHING as negative in that massive social movement.

However much I consider the Great Socialist Cultural Revolution to be an event of supreme importance in the development of Marxism-Leninism it did, ultimately, fail. It failed for reasons which have to be understood if the same mistakes are not to be repeated. To deny that fact is as destructive of the movement as is the approach of the revisionists who hope it just ‘goes away’.

6

The inclusion of this short section – about the People’s Republic of China being able to take its rightful place at the United Nations Organisation and on the Security Council – seems to be strange and, really, unnecessary when there were more important issues to bring to light.

Here there seems to be a criticism of China’s policy of ‘isolation’, that China could have played a greater role in the promotion of revolution and Socialism if it abandoned its ‘close-door policy’ in relation to other countries.

It was only Albania that had been pushing for the PRC as being ‘the only legitimate representative of China to the United Nations’, which was eventually achieved on 25th October 1971. The only other country that had fought for Chinese interests before was in the early 1950s when the Soviet Union boycotted the Security Council of the UN due to the refusal of the organisation to accept the People’s Republic of China as the legitimate representative of the Chinese people. (This boycott was then used so that the imperialists in the UN could vote for UN sanctioned intervention in Korea.)

7

As stated above one of the reasons there’s such an angry tone to much of this letter was due to the fact that when the Chinese unilaterally withdrew aid, including military aid, they did so in a manner that exposed Albania’s military potential to the gaze of possible enemies of the People’s Republic of Albania. This had a bit of history, Albania being denied heavy armaments, by Chou En-lai, both in 1968 and 1975. Stating that all such weapons would not be enough to counter any threat from either US/UK imperialism or Soviet ‘social-imperialism’ Chou suggested, in its place, Albania forming a military alliance with Yugoslavia and Romania.

This would have riled the Albanians on a number of levels. By making reference to the small size of the country and population Chou was emulating the approach of Khrushchev in the early 1960s. He (Chou) was also suggesting an alliance with one of the countries with which Albania considered a military threat rather than a potential ally. This seems strange when Chou was supposed to be an astute politician (perhaps too much a politician than a Communist) and would have been very much involved in the debates prior to the political schism between China and the Soviet Union in 1963. He would have known that Albania would see such an alliance as a back door way for Tito to achieve his aims of a greater Yugoslavia in the Balkan region. It was also reminiscent of the sort of interference in the internal affairs of Albania that the country had had to endure from the Soviet Union until 1961.

It also displayed a total lack of understanding of the Albanian way of thinking, its attitude towards independence and its long history of fighting against foreign invasion, even before the formation of an Albanian Communist Party.

To look at geopolitics merely through statistics is the way that imperialism has looked at and treated the rest of the world over the last two or three hundred years. That’s why straight lines determine the borders in Africa and the Middle East which take no account of the people living on either side of those lines. This was a politics of ‘spheres of influence’ where different European countries would grab as much of the territory of the colonial peoples as they thought they could control. This was the politics of the Sykes-Picot Agreement (of 16th May, 1916) which divided up those parts of the Ottoman Empire in the Levant between the British and the French after the First World War. Such an ignorant and chauvinistic approach has led to the conflicts, coups, internecine wars and invasions and interventions which have dominated the region for the last seventy years, causing untold suffering on the people on the ground.

This led to the creation of the state of Israel and the internationally sanctioned crime which is the robbing of the Palestinian people of their land, their security but never their dignity – a crime of which the world and all its people should be ashamed to allow go unpunished. Marx said the British workers would never be entirely free if they did not resolve, at the same time, the situation of the oppression of Ireland. In the same way the people’s of the world will never be entirely free if the Palestinians continue to suffer as they have over the best part of a hundred years.

But such an approach to geopolitics is not what should be emanating from a country that considers itself Socialist. Power politics is what Socialism is not about. This is Great Nation Chauvinism, this is the policy which the Chinese accused the Revisionist Soviets of following at the same time as they were attempting to impose a similar policy on Albania. It was when erstwhile Socialist countries played the same game as the imperialists that they started to lose credibility, both at home and abroad. The Soviet intervention in Czechoslovakia in 1968, the Soviet intervention in Afghanistan from 1979 onwards and the Chinese invasion of Vietnam in 1979 are cases in point.

Why would China want to impose its will on small, isolated and surrounded by enemies Albania?

Not only is that a not very fraternal attitude to take it displays a total ignorance of the psyche of the Albanian people. In many of the historical pamphlets produced by the Foreign Languages Press (and now published on the China pages of the BannedThought website) one thread that runs through them is the inability of the western, imperialist powers too understand the Chinese people. This was due to a mixture of ignorance, arrogance and racism. Such an approach only bred the many hundreds of thousands of men and women who joined the Chinese Communist Party and took part in the National Liberation War. Why then did the Chinese Party think they could approach a fraternal country in a similar manner?

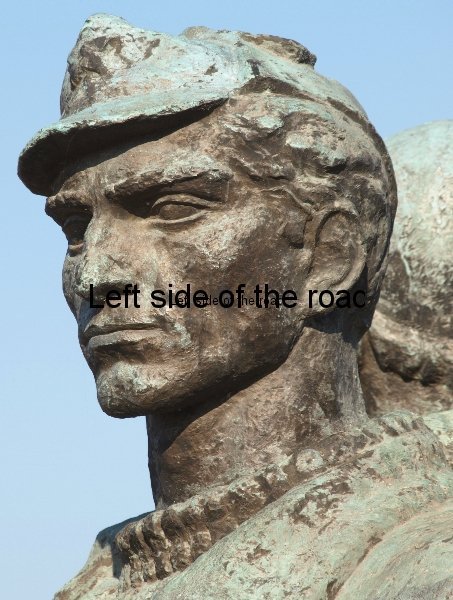

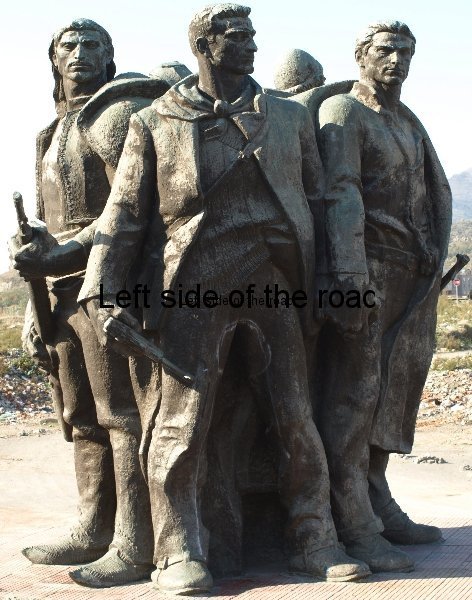

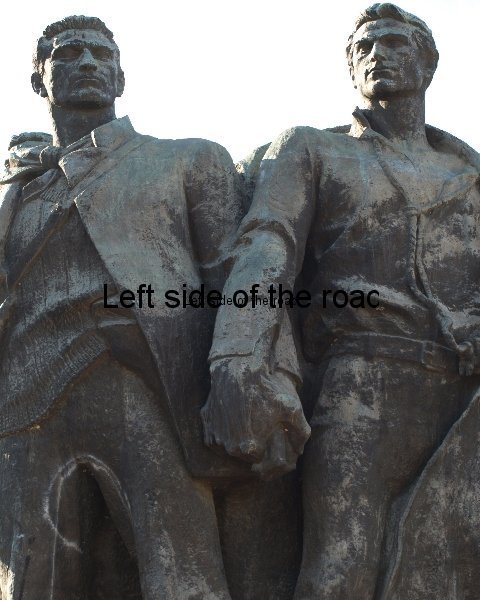

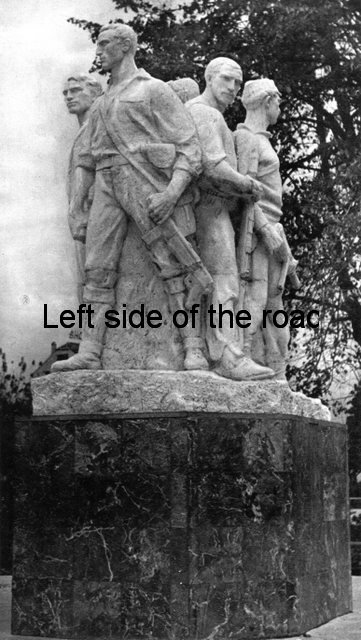

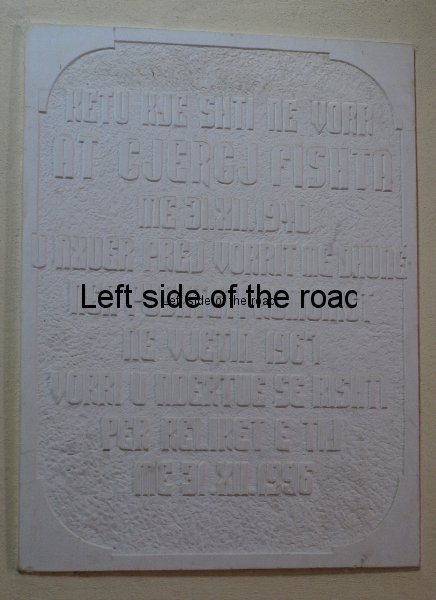

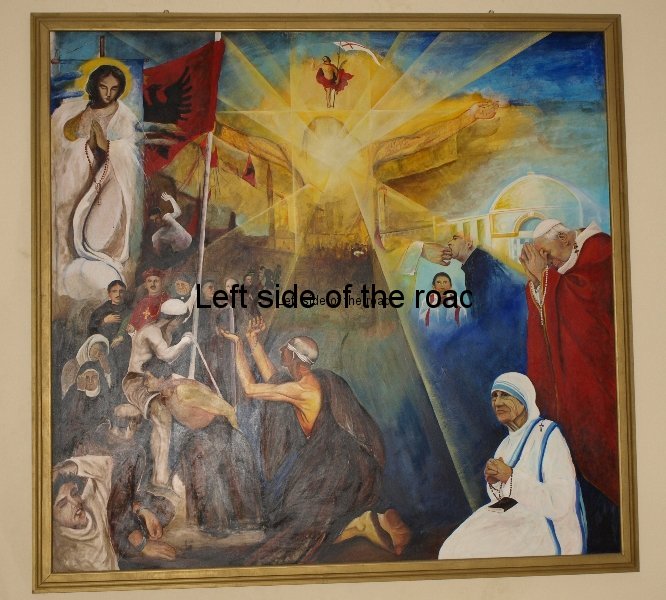

Anyone who had even the slightest knowledge of Albania and its history would not make such a mistake. Skenderbeg, a 15th century aristocratic military leader, has been a symbol of Albanian independence since his death in 1468. Statues commemorating his exploits and those of other independence fighters in later centuries against foreign invaders were erected in Albania even at the time of the Fascist Zog, before he fled the Italian invasion in April 1939. Statues of nationalist from the pre-National Liberation War period were erected after the defeat of the Italian and German Fascists throughout the country. Socialist Realist artists, painters and sculptors, created works of art celebrating the struggles of early independence fighters right up to the end of the 1980s when everything in Albania fell apart. They appeared on countless lapidars (the Albanian monuments) and far outnumbered statues to Marxist-Leninist heroes such a Lenin and Stalin. Even today, when independence is just a word and has no real meaning in the political or economic sphere in capitalist Albania these heroes are remembered on important historical occasions and their monuments cared for whilst other, more recent structures, are allowed to decay.

And it was into this world, when those in the leadership of the PLA and Albanian Government had, almost to a man and women, been active fighters in the National Liberation War against the most powerful enemy the country had ever had to face that the Chinese Party sought to tell them what to do. Is it any surprise they received the reaction they did?

Here the Chinese made a similar mistake in not understanding the feelings of a people – the people not just the leadership – as they had when they allowed the conflict on the Usurri River to get out of hand.

8

The PLA and the Government of Albania weren’t the only ones to be surprised to hear, in the summer of 1971, of the proposed visit of Nixon to Peking. One day you’re on the streets demonstrating against the murderous war that the US was waging against Vietnam, attempting in all ways (short of using nuclear weapons – although that was only avoided by a whisker) to destroy both the country and its valiant people, often alongside revisionist supporters of the Soviet Union where you are arguing of the superiority of the Chinese viewpoint, the next you are having to justify the unjustifiable.

I was in that situation and I’m sure many Marxist-Leninists, Maoists, were as well.

Nixon’s role in much of the world was seen in the context of him being a bent and corrupt President, lying, cheating, agreeing to the burglary of a Democratic Party office, secretly taping conversations with those he met in the Oval Office and, obviously, his continuation of the war in Vietnam. We might also have known of his role when, as Vice-President to Eisenhower between 1953 and 1960, he made regular visits to South Vietnam and was instrumental in supporting the final days of the French war against North Vietnam as well as paving the way for the introduction of US troops in the battle zone after the ignominious defeat of the French at Dien Bien Phu in May 1954.

Those in the US would have known him also for his anti-communist role in the House Un-American Activities Committee and the witch hunt that took place in many walks of life, from the late 1940s until the mid 1950s, and I know that some members of various Maoist groupings in the US left their different parties in disgust at the very idea that such an individual would be invited to Peking.

Now (in 1971) this staunch anti-communist was being invited to the capital of what many of us believed to be one of the standard bearers of world revolution and national liberation. This was also taking place at the same time that B52 bombers were raining death and destruction upon the people of North Vietnam. Flying so high often the people didn’t know what was happening until dozens of 500 and 750lb bombs landed on their towns and cities. And this bombing didn’t cease after Nixon’s visit.

I think it’s worth quoting here a little from the Letter of the CC of the PLA to the CC of the CPC, sent on 6th August 1971, just after the Albanians had learnt of the proposed visit – via international news agencies.

‘Welcoming Nixon to China, who is known as a frenzied anti-communist, an aggressor and assassin of the peoples, as a representative of blackest US reaction, has many drawbacks and will have negative consequences for the revolutionary movement and our cause.

‘Talks with Nixon provide the revisionists with weapons to negate the entire great struggle and polemics of the Communist Party of China to expose the Soviet renegades as allies and collaborators of US imperialism, and to put on a par China’s stand towards US imperialism and the treacherous line of collusion pursued by the Soviet revisionists towards it. This enables the Khrushchevite revisionists to flaunt their banner of false anti-imperialism even more ostentatiously and to step up their demagogical and deceitful propaganda in order to bring the anti-imperialist forces round to themselves.’

The Albanians saw this visit in many ways as a repudiation of all that had passed between the CPC and the CPSU during the years of the International Polemic and the Great Socialist Cultural Revolution (which was still taking place, although now possibly with less intensity). This allowed the Soviet revisionists a respite. How could they be criticised for their closer relationships with the US imperialists if the Chinese were inviting its highest representative to their capital city?

The CPC didn’t even deign to reply to this letter from the PLA.

What also angered the PLA was that they had not been consulted, or even informed, of this visit and had to read about it in the international media. Considering the stance that both the parties had taken in the struggle against revisionism in all its forms the PLA saw this as a betrayal of the fraternal relationship they thought they had with the CPC.

To add insult to injury the CPC found excuses not to send delegates to the 6th Congress of the PLA that was due to take place at the end of 1971. Now the periodic Congresses are the high point in the life of any Communist Party. For a Party in power it’s an opportunity to review past successes, analyse any mistakes and to look forward to the future. For a Party in power it was also an opportunity to demonstrate the connections it had in the world. For the Chinese not to send a delegation was a public statement that the close relationship that had existed for the previous eight years was no more. From that time the two parties grew more and more apart.

9

The ‘Three World’s Theory’ was a strange one. When it first came out I can’t remember anyone saying anything more positive than ‘what’s this mean?’ or ‘where did this come from?’. It purportedly came from Mao but it lacks the clarity of thinking and clear direction that is characteristic of most of his published work. It’s even more strange when we remember that the first and perhaps the only time it was propounded in a major public forum was on 10th April 1974 at a Special Meeting of the United Nations General Assembly when Teng Hsiao-ping ended his presentation by saying that China was part of the Third World.

All the points made in the letter of the CC of the PLA are valid. The ‘theory’ is a dog’s breakfast. It doesn’t make any sense other than to make the point that China is on the same side as any country, whatever its political system, as long as it’s against the countries that China doesn’t like. This isn’t a Maoist theory – however hard the revisionists want to tie it to him. This was just another tactic of those in the leadership who had been ‘rehabilitated’ after spending the best part of ten years in the political wilderness, or prison.

This theory is more of one of the first shots that the revisionists, who were gaining in strength within the CPC, were able to fire in the coup they were planning – to take place soon after the death of Chairman Mao.

Like so many of the declarations and decisions of the CPC in the 1970s the aim of the dissemination of this ‘theory’ was primarily to cause confusion in what was becoming an increasingly divided and split revolutionary Marxist-Leninist movement throughout the world.

10

Although it was not obvious generally that the relationship between the PLA and the CPC was becoming strained the way that the letter puts events in their chronological order makes it clear that the gap between them was getting greater, the pace increasing after Nixon’s visit to China in 1971.

Throughout this document there are many references to letters and requests from the PLA continually being ignored by the CPC. This wasn’t even the case at the height of the International Polemic. At that time each side published, in full, documents from the other. The Soviet revisionists at least sought justification of their erroneous ideas, if the CPC considered it was correct why didn’t it make a similar effort to ‘correct’ the PLA?

This aloofness of the Chinese only serves to give credence to the points that the Albanians make. In this section the letter states that the Chinese accused the PLA of criticising and attacking the CPC and Chairman Mao on the occasion of the PLA’s 7th Congress in 1976. As the letter says, there’s no reference whatsoever to that happening in any of the documents made public and published soon after the Congress. Furthermore, as I have stated above there was a regular flow of positive articles and references to China and the friendship between the two countries up till the end of 1976. The majority of articles printed in English language publications (and here I’m really referring to ‘Albania Today’ and ‘New Albania’) were mainly translations of work that had appeared in various Albanian language publications, so there doesn’t seem to be any proof that the Albanians were doing anything other than try to maintain the impression that all was well between the two Parties and countries.

This meant that no delegation from a previously fraternal Party was invited to Peking but the world and its dog was. Only a cursory glance at the copies of Peking Review of the period 1974-76 will demonstrate that for the last couple of years of his life so much of Chairman Mao’s time was taken up by greeting so-called ‘dignitaries’ who had been invited to visit Peking . As is stated in the Albanian letter all kinds of ‘kings’, despots, thieves, cut-throats and murderers were welcomed into the Chairman’s presence. Among those were ‘leaders’ who were hated by their people due to their political institutions, economic and social policies which left poor people poorer each year and almost always under a constant threat of violence if they dared to challenge the ruling group. The only rationale for all of these visits was that they were of ‘the third world’, the same world which China also inhabited.

Although some of them could be grouped as ‘progressives’ in that they were leaders of countries which had recently freed themselves from colonial oppression the majority were representatives of capitalism at best or outright reaction and fascism at worse. American Presidents continued to visit Peking and even Nixon made another, official, visit after he’d been disgraced and forced to resign. The Chinese seemed to be embracing Islam at the time as there were a number of visitors from those countries dominated ‘Islamic Republics’. Dictators such as Mobuto were welcomed and for some bizarre reason Imelda Marcos from the Philippines was invited twice. In a move that would have been especially difficult for the Albanians to stomach was the invitation of a high level delegation from Yugoslavia.

In total there were at least 47 of these delegations in the last two years of Chairman Mao’s life and, as stated before, would have had the effect of separating him from the real events and developments that would have been taking place in the Chinese Party and Government. This number of visitors would have almost certainly had been greater if it were not for the fact that a number of high level members of the Party were also to die in that period, making Mao and other leaders unavailable to receive visitors on those occasions.

Chairman Mao was getting old and by forcing him into this role of meet and greet was taking him away from any real involvement in the policies of the country and keeping him away from the scheming that had to be going on behind the scenes – there’s no other way to explain the speed and success of the revisionist coup that was carried out so soon after his death. He had said that there would be a need for many more Cultural Revolutions but he was not to be around to initiate another.

11

The PLA had long-established the rule that they would not publicly make statements about the leadership in other Marxist-Leninist parties – until the situation had developed such as it had by the time of the meetings in Bucharest and Moscow in 1960. Likewise they refused (in the couple of years after the death of Chairman Mao) to condemn some of the leadership that had been replaced or imprisoned in the coup that took place at the end of 1976.

However, there’s a telling quote from this letter which quite clearly expresses the view of the PLA in relation to the Chinese leadership as was in 1978.

‘The present Chinese leadership has wanted our Party to support its illegal and non-Marxist-Leninist activity to seize state power in China. Our Party has not fulfilled and will never fulfil this desire of the Chinese leadership. The Party of Labour of Albania never tramples on the Marxist-Leninist principles, and has never been, nor will it ever be anybody’s tool.’ page 17, column 2.

Within a short period of a year or so, with the publication of Hoxha’s ‘Reflections on China’, the world was to get a better idea of how he had seen the situation within and the relationship with China. Probably more than any other document this led to what became, in some parts of the world, such a vicious and acrimonious split in the international Marxist-Leninist movement

Conclusion

The letter shows how the PLA saw the situation in, and with, China in 1978. There are few of these criticisms that I do not share. When we look back at the almost 40 years since the publication of that letter and take into account what has happened during that time we can see that, in many ways, the letter was prescient in that what it suggested would happen, when a Party leaves the road of Marxism-Leninism, has indeed happened in that erstwhile Socialist country.

As I’ve stated above the acrimony that developed in the late 70s – where I think some were treating Mao as some perfect being who did no wrong (something I’m sure Mao himself would have thought ludicrous and laughable) – was unnecessary, destructive and caused irreparable damage to the International Communist Movement at the time. It also hasn’t left us so many years later with any conclusions which could be of any use to future revolutionary movements.

I accept and argue that the Great Socialist Cultural Revolution – and the necessity for countless such revolutions before Communism can be achieved – is one of the greatest contributions that Mao made to Marxist-Leninist theory. However, it failed. It failed not least because one of the greatest proponents of the reactionary theories that would have led to the re-introduction of capitalism in China, Teng Hsiao-ping, was allowed back into the higher echelons of the Party whilst Mao was still alive. Who promoted such a rehabilitation I do not know, nor the why.

What is certain, however, was that the Party invited the viper back into its inner sanctum. Carrying out exactly the same tactics for which he was imprisoned and disgraced in 1966 Teng was able to create a situation where the revisionists were able to gain control of the Party in a coup within a matter of weeks of Mao being placed in his mausoleum. This was the case even though he underwent widespread public criticism, particularly by those in the Chinese leadership that became to be known as the ‘Gang of Four’ (Jiang Qing, Zhang Chun-qiao, Yao Wen-yuan, and Wang Hong-wen) following the Tangshan earthquake of July 28th 1976.

Within a few short years all the political advances that had been achieved since the declaration of the People’s Republic in October 1949 became a thing of the past, sacrificed on the altar of getting rich is glorious. Some fought against this but not enough.

In the years following the letter Albania carried on, now very much alone in the world. As time drew on matters became more difficult and increased the opportunities for those with the desire to foment discontent. When Enver Hoxha died on 11th April 1985 the line of the Party softened and the PLA was unable to provide the leadership it had provided for 45 years during the construction of socialism.

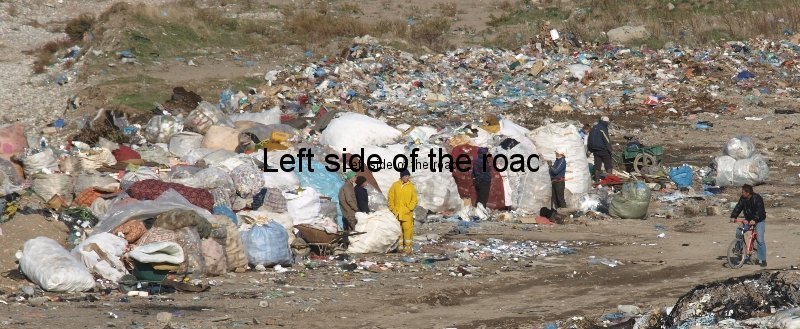

Emboldened by events in other parts of Eastern Europe (and with China continuing down its capitalist road) the reactionaries were successful in their counter-revolution in 1990.

Socialist revolutions are hard to foment, harder still to ensure success, even harder to maintain.

If the world is to see a new wave of revolutions in the 21st century, when the necessity for such is even greater than it was in the 20th we have to make sure that we understand past mistakes as fully as possible. Lenin learnt from the 1871 Paris Commune and published his ideas, criticisms and suggestions on how not to make the same mistakes in ‘The State and Revolution’ (first published in August 1917, only a couple of months before the October Revolution).

The material we have to study to understand is vast and to do the investigation justice and to be practical we have, perhaps, to be selective. The letter of the CC of the PLA to the CC of the CPC is one of those that should be on that list.

28th April, 2017

More on Albania ….