Monument to the 15th Partisan Assault Brigade – Elbasan

Ukraine – what you’re not told

Monument to the 15th Partisan Assault Brigade – Elbasan

I must admit I have a little bit of a difficulty in working out exactly what the shape of this monument is supposed to represent. It’s like a huge belt or a ribbon. It starts at the back on the left-hand side and then comes back on itself in a big curve towards the front, where you have the main sculptural group, and then gently curves towards the back of the monument and finally straightening out slightly as it gets to the edge at the right-hand side – it’s a bit like a huge hook.

Not sure exactly the dimensions but it’s roughly 3 metres in width, which remains the same along its whole length, which I would estimate around about 15 metres in total.

There’s a sense of movement in this static, heavy concrete structure.

There’s a physically large clue on the left-hand side that it might be representing an ammunition belt because there are huge bullets on the extreme left. However, these cartridges seem to get absorbed by the lapidar and apart from the top of the casings disappear as they get close to the main sculptural group, only to re-emerge again at the edge of the flag.

The whole structure is about 2 metres above the ground – sometimes slightly less, sometimes a bit more – and the monument itself sits on two piles of rough rocks which are cemented together. This introduces the idea of the mountains, which is quite common in Albanian lapidars. On the left these rocks provide support directly underneath the sculptural group and then towards the right-hand side is another pile taking the weight.

The principal artistic element and the image which immediately draws your attention is the stone bas relief of four Partisans, grouped together above the left-hand support pile.

The individual which dominates the image is the male figure of the standard bearer who is on the left of the group – and slightly higher. We also see much more of him, virtually the whole of his body above the waist. He stands face on but his head is turned to his left so we get a right profile. His right arm is raised and his hand grips the flagpole near its top point whilst his left hand grips the pole at waist level. He is a Partisan in full uniform, wearing a cap with a star at the front and tied around his neck is what would have been a red scarf. On his left hip is a buttoned-up, leather holster, only the butt of the pistol visible.

The flag, the flag of the Communist Partisans, flutters in the wind that’s coming from the left as we look at the image. The very top of the flag is the only part of the tableau that breaks the confines of the concrete shape. This would have been a red flag and on it would have been a black, two-headed eagle (an image used by Skenderbeu in the 15th century, through the period of Socialist construction between 1944 and 1990 and to date). However, during the National Liberation Anti-Fascist War and the period of Socialism there would be a small gold star in the space just above where the two heads separate.

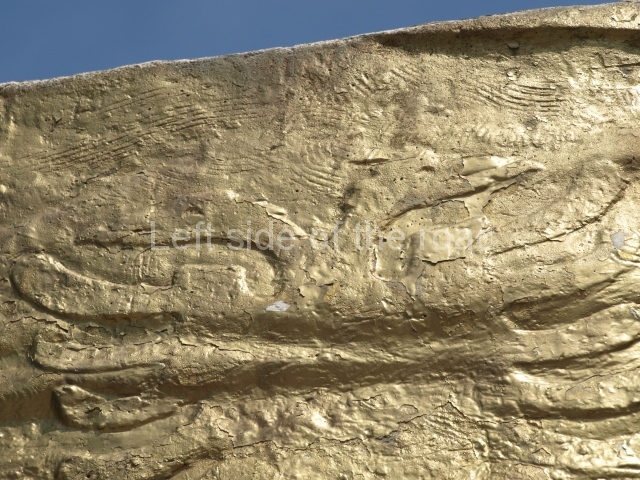

The stars were the target for the reactionary, fascist, nationalist forces that gained control of Albania in the early 1990s and many of them on lapidars throughout the country have been the subject of masking or obliteration. Although most of the monument in Elbasan remains in good condition the star on the flag has been erased. If you look carefully at the space above the eagle heads, almost to the top of the lapidar, it’s possible to see that someone has applied ‘fresh’ plaster to level out the area and erase the star. The parallel marks as evidence of this ‘alteration’ are to be found nowhere else on the lapidar.

Missing star

Two of the other Partisans, one female the other male, are similarly looking towards their left. This is where the action is and they are on the way to the battle. They are also in profile but there’s still a lot of information, even though we don’t see much of them.

The female Partisan is partially hidden by the standard bearer but she is also in uniform. She wears a cap and the edge of the star is evident on the front, her long hair flying behind her as she moves quickly forward. It also looks as if she has a red scarf around her neck. In virtually all the lapidars relating to warfare when a woman is depicted she is always armed (as in the mosaic on the facade of the National Historical Museum in Tirana) although the men aren’t. This lapidar is no different and the sharp end of her rifle is seen poking out behind the head of the fighter on the right of the group.

In front of her is a young male Partisan from the countryside. In the lapidars the distinction is often made about those Partisans from the countryside by depicting them in the traditional clothing of the mountain people. He’s not in a formal uniform but is dressed in a woollen vest, his shoulders and arms bare. Around his forehead is a sweat band, the knot tied at the back of his head. But his political allegiance is shown by the (red) scarf around his neck. At waist level he holds a sub-machine gun, his right finger on the trigger and his left hand holding the gun at the magazine. His posture is the same as the woman, moving forward towards the battle, his left knee bent to give the impression of the effort to get there quickly.

The fourth member of the quarter is not moving forward. He is an older man from the countryside, he is wearing a waistcoat and on his head a traditional cap (a qeleshe) but one on which is a star. All the people in this image are Communists. Additionally, it’s almost a trope when it comes to depicting older men from the mountains, he’s boasting a bushy moustache. He’s aiming his rifle and pointing downwards with his right finger on the trigger and holding the barrel of his rifle in his left hand. The Partisans, knowing the terrain, would always aim to select the location that was to their greater advantage and this representation of firing downwards appears in other lapidars such as the amazing star at Pishkash. And the mountain top design of the plinth supporting the monument adds to this impression of mountain warfare, he seems to be shooting out of the bas relief into a mountain environment – like someone walking out of a screen of a film.

Everything indicates that this is an ambush of a Nazi column in the mountains.

Where the right hand side of the flag ends we can see the top casings of three gigantic bullets. These then merge into a large, five pointed star which appears to be leaning away from the lapidar at the top but which merges into the concrete at the bottom. It’s more than half the width of the concrete ribbon, so more than a metre from point to point. The very tops of the casings of the cartridges then reappear briefly on the other side of the star until they finally disappear.

The concrete base on which the bas relief sits has curved slightly towards the back of the lapidar creating a partial circular space in the rear but then the panel straightens up and extends for about half the of the total length to the right.

The top left-hand quarter of this now unadorned panel has been plastered so that it provides a smooth face on which are painted (now) in red letters the following;

Partizanet e Brigadës XV S. duke luftuar me popullin kundër pushtuesit nazist gjerman e tradhëtarive çliruan më 11 nëntor 1944 qytetin e Elbasanit

which translates as

To the Partisans of the XVth Assault Brigade who, with the people, struggled against the German Nazis and traitors to Liberate the city of Elbasan on 11th November 1944

(This re-writing of the inscription in red paint must have been completed around the beginning of 2015 as the image in the Albanian Lapidar Survey (Volume 2, page 205) catalogue shows a different version.)

Towards the extreme right-hand edge of the monument there is something attached to the concrete – looking like a rectangular box. I’m not too sure whether this is something which was there originally and supporting another element of the story (but can’t really imagine what). There are signs, holes and general markings, that indicate that whatever was there was more extensive.

(One of the problems of there being so many lapidars to document is that I don’t always ‘see what’s there’ at the time of my visit. It’s only when time and magnification on the computer screen that some aspects become ‘visible’. If I ever get the opportunity to return to Elbasan I’ll try to remember to ask the pertinent questions.)

Generally, this lapidar is in a very good physical condition. There doesn’t appear to be any damage (apart from the mystery markings on the extreme right-hand side) and although it’s unlikely that the bas reliefs would have been painted in gold paint originally at least the painting has been done with an element of care and professionalism, as has the signwriting of the inscription.

Unfortunately, there’s no information available of the artist who created this lapidar – nor of the date of its inauguration. The features of the quartet are very clear, distinctive and detailed – you would recognise the models (I’m sure, if you saw them. This would seem to indicate one of the more accomplished sculptors and it’s very pleasing to see that the detail has remained intact despite the troubled times the country, and consequently the Socialist monuments, went through – especially in the 1990s.

Its present condition and the fact that has had a relatively recent ‘renovation’ and attention would seem to indicate that it has local support and protection. Whether that be from the local community or the municipality is impossible to say.

Nonetheless, this is an important lapidar in the country as it has attributes which I haven’t seen repeated elsewhere.

Location

In the large square created at the junction of Rruga Kadri Hoxha and Rruga Çerçiz Topulli. This is a bit of a transport hub and looks like it might be the site of a recently installed roundabout. It’s just over half a kilometre east of Elbasan Castle in the centre of the town.

GPS

41.11280498

20.07384798

DMS

41° 6′ 46.0979” N

20° 4′ 25.8527” E

Altitude

137.4

More on Albania ……