Komani Lake – The most impressive ferry trip in Europe?

I’ve done the Amazon, the Yukon and the Zambesi but you have to go a long way to beat the beauty and splendour of the Lake Komani ferry journey from the hydro-electric dam at Koman to the port of Fierza, on the way to the town of Bajram Curri – and it lasts for less than three hours.

The easiest way to make this trip is to start from Skhodër (practical details are below). You have to get up early but it’s not as bad as starting from Tirana. If you stay in the centre of Skhodër you needn’t worry about oversleeping as the call to prayer at 05.20 from the Al-Zamil Central Mosque is loud enough to wake the dead – although I’ve never seen that many people in the streets when I’ve eventually emerged.

The first part of the journey is to the town of Van i Dejës and once you leave there you are immediately in the countryside offering a taste of what’s to come. The valley here is much wider than on the lake itself but this journey provides an introduction to the vegetation and the aspect of the mountains as you steadily climb up to about 400m at the Koman dam. After going through a long tunnel you arrive at a small and simple landing stage.

The lake was formed when the hydro-electric power station at Koman, on the Drini River, was completed in 1986 and a regular ferry service was a cheaper and more environmental form of transport instituted as soon as the project was completed.

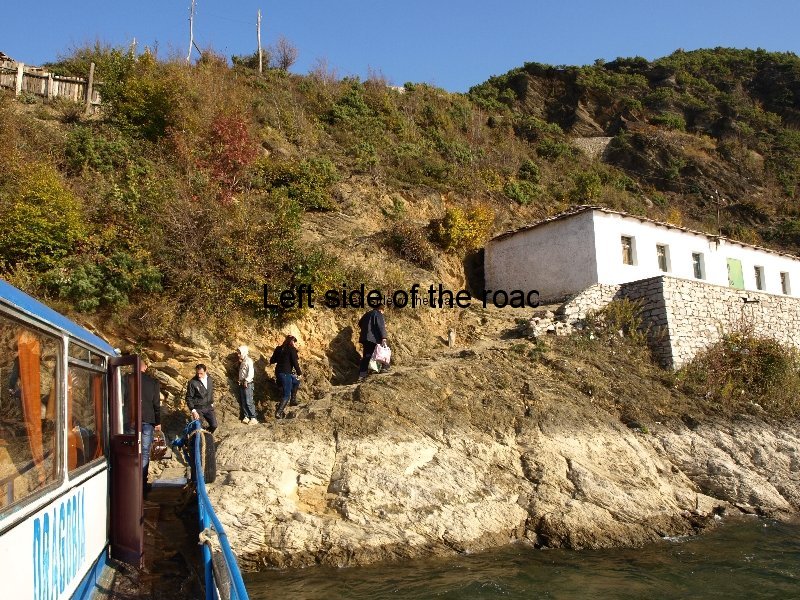

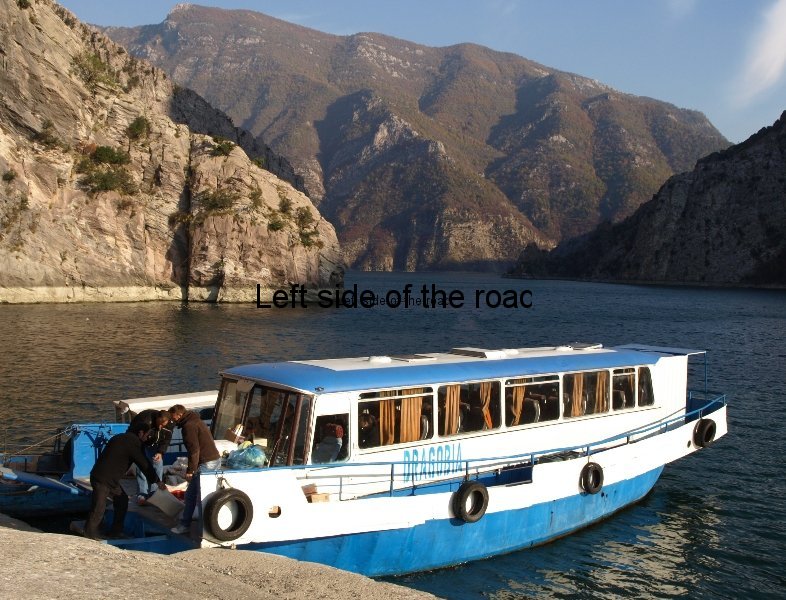

You’re not about to embark on one of the expensive luxury river cruises that are becoming more of an industry in many parts of the world. Here you share the space with the people making their way from their homes to the rest of Albania, taking their goats to slaughter, machines to be repaired, or replenishing their stocks of Coca Cola. The boat, which once plied its trade along the rivers of Italy, has seen better days but manages to provide the people who live along the length of the lake with a daily service towards the Albanian towns of Skhodër or Tirana in the west and south, or the town of Bajram Curri (for links to Kosova) in the north.

For a time there were no other ferries running than the second hand Italian foor passenger ferry but the increase in tourism and probably a desire of car drivers not to have to get to the other parts of Albania without having to go into Kosovo has meant that, at least in the high season, there are two car ferry options.

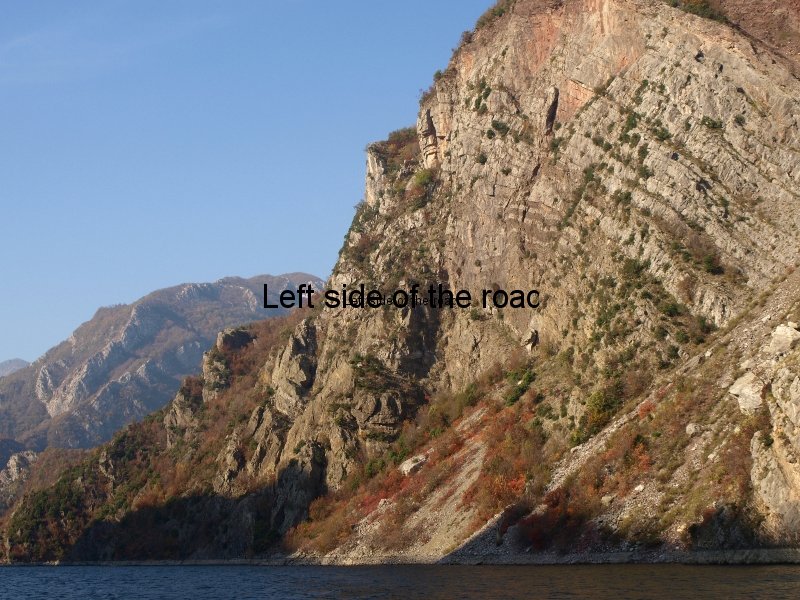

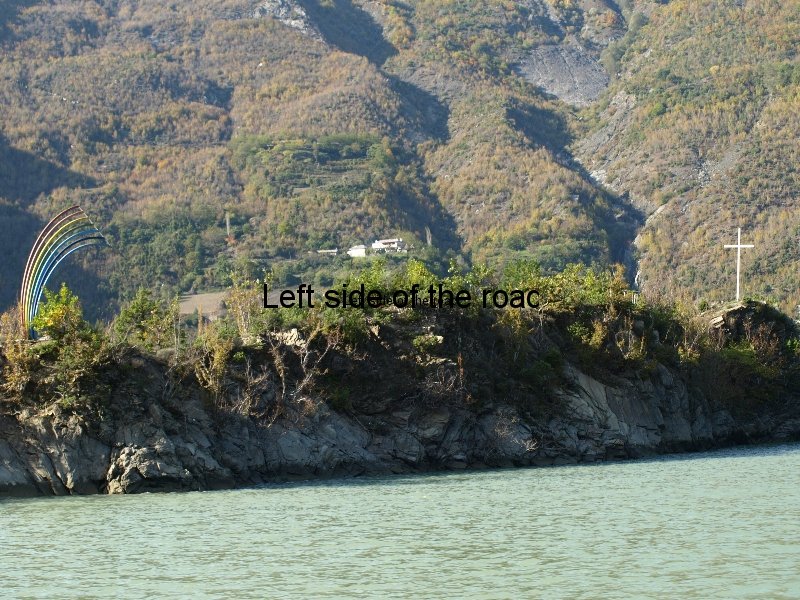

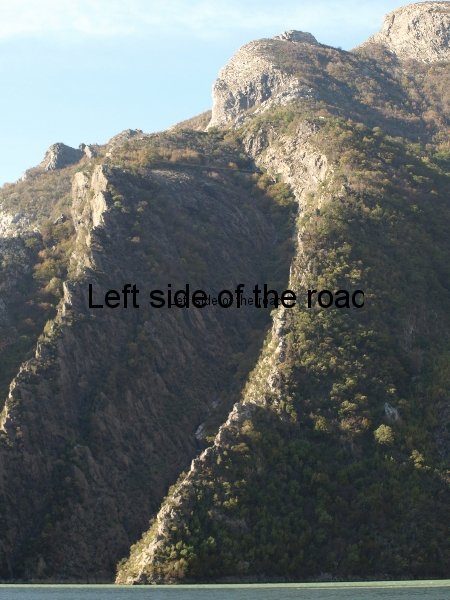

As should be no surprise the locals just take the beauty of the surroundings for granted. After all they can just look out of the windows of their homes to appreciate the magnificence of the mountains, some of which soar to a height of 1700m. But this is a relatively narrow man-made lake and the route of the original river can still be seen as the boat twists and turns, heading for seeming impenetrable rock faces as it makes its slow and unhurried progress, just chugging along from one makeshift landing stage to another.

I’ve made this journey three times now but always in the autumn, fortunately when it has been clear and sunny but when it has been bitterly cold in the shade. With a wind that cuts through you like a knife you have to use the vessel as a wind break if you intend to be outside for long. In these conditions the couple of glasses of home-made raki in the café at the dam become a wise investment – the body is numbed before the cold can get to you. In such circumstances the intrepid traveller will have the outside to themselves, apart from those times when the smokers find they can’t hold out any longer.

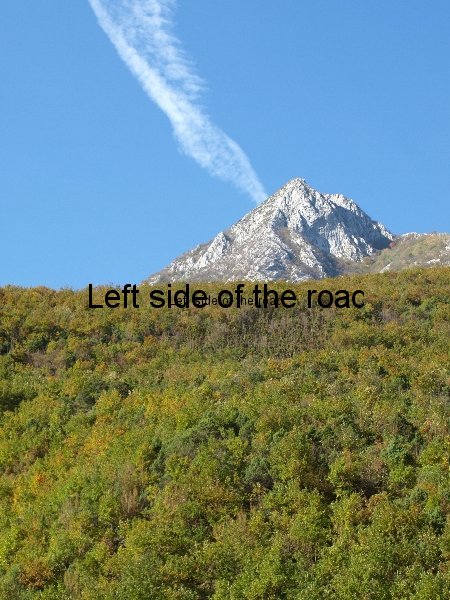

The boat is dwarfed by the sheer walls that close in on many stretches of the trip but when the waters open out you have the opportunity to see the high peaks of one of the many mountain ranges which constitute Albania. The vegetation is starting to prepare for the cold of winter when you go through in November but as different plants close down for the summer they do so at various times and you witness the transformation through the colour spectrum from almost red, to amber and brown. I’ll have to try to make this journey in the spring when the land is awakening and preparing for the long, hot summer.

The walls of the cliff faces are also an education in the evolution of the very mountains, showing the different layers of sediment set down millions of years ago and then twisted and bent so that they are almost going back on themselves.

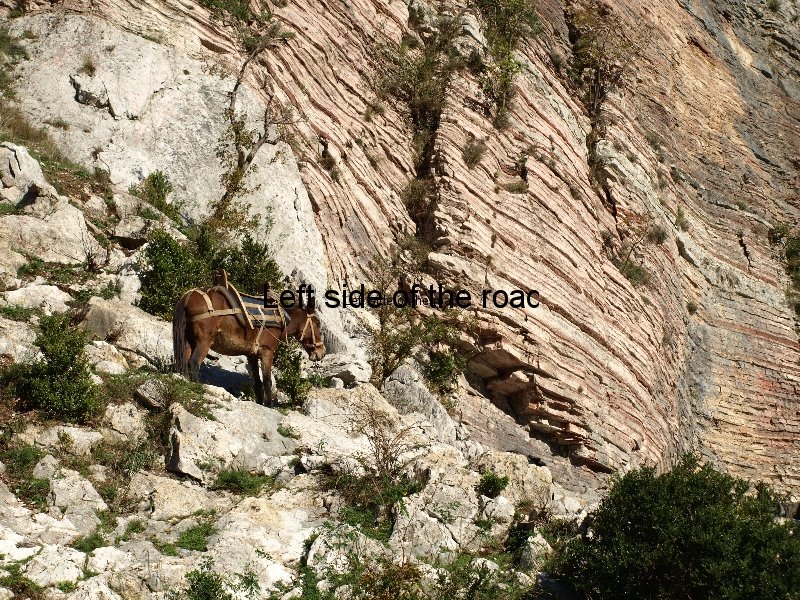

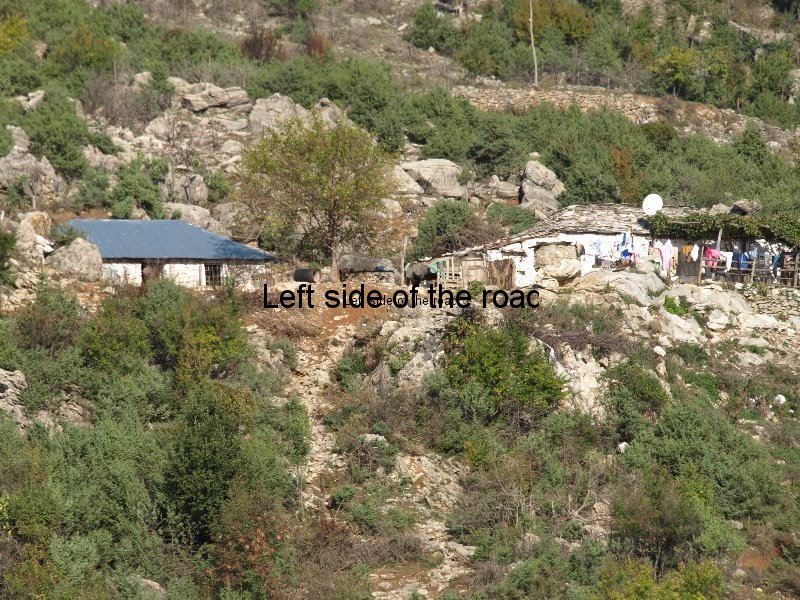

At times there’s enough flat ground close to the lake and you’ll pass a small, seemingly isolated farmhouse, with outbuildings. However, as in all such places in the world, hidden from view is a whole network of paths and mule tracks that allow communication between the mountain community. The ferry is merely the more obvious and public link between these communities. Many other, sometimes quite large settlement can be seen much higher up the side of the hills, making for a particularly difficult trek back home from the lake, hence the use of mules.

When the boat approaches the shore often it’s not until you hit the land that you’re aware a path is there at all, but when people leave the ferry it’s not long before it’s impossible to spot them as they make their way to their homes.

As with all these forms of transport you’ll often encounter the unexpected. On one trip a rowing boat rushed across the lake to where the ferry had pulled in. I thought to drop off a passenger but the next thing I knew the small, metal boat was being towed behind us, making for interesting maneuverings at future stops. How the small boat wasn’t hit and tipped over was beyond me.

Bird life is sparse in the autumn, many migrating further south for the warmth, but the country is home to many species and as there’s not that much traffic on the lake (only one return journey a day with a boat of any size) you are almost on top of the wildlife before they know you are there.

All along the route, even in the most remote parts of the journey, you’ll notice the power lines straddling the lake as they provide power to the isolated villages and settlements along its length. The people were not ignored when the project was planned in the late 70s, as is the case in so many parts of the world where major construction projects change forever their lives but they don’t get any benefit themselves.

By the time the boat reaches the end of the journey at Fierza there’s not normally that many people left on the boat, after all you’ve just travelled on the local (floating) bus.

Practicalities

Furgons (normally two) leave Skhodër every morning between 06.00 and 06.30 from the bottom end of Bulevardi Skëndërbeu, on the right hand side as you leave the town centre, just before Rruga Antikomunist Hungarez (that leads to the railway station) and before the road narrows. If you stay in one of the hotels (DON’T take the advice of the friendly yet strangely dangerous woman in the Tourist Information Office who gives the impression she knows everything but always gets a vital piece of information wrong.) The journey takes a little under 2 hours and costs 400 leke. It might stop for a short while in Van i Dejës but always aims to get to Koman in time for the ferry.

On arriving at the ferry terminal, right beside the dam, there’s a café for tea and raki.

Just wait for the ferry. It normally arrives just before 09.00 but everyone else there is in the same boat, or will be eventually, so there’s no need to panic. There’s only one boat a day, each way. Some guide books will tell about car ferries. There are two of them and you will see them when you arrive at Fierza but they don’t run any more.

The cost of the journey from Koman to Fierza, one way, is 500 leke and this will be collected en route.

The journey takes just under 3 hours.

On arrival at Fierza get off the boat on the left hand side bank. Here there will be some sort of transport to take you the short journey to Bajram Curri. DON’T hang around or dilly dally or you’ll find yourself stranded, at least for a while. The furgon/taxi to Bajram Curri takes about 15-20 minutes and costs 200 leke.

If you want to take the ferry from Bajram Curri to Koman you need to catch a furgon that leaves the roundabout at the top end of town (beside the looted museum and the large statue of Bajram Curri himself) at 05.30 in order to be at Fierza for 06.00.

If you want to return to Tirana from Bajram Curri by road there are furgons that leave from that roundabout during the morning each day, going via Kosova.