The ‘Hanged Women’ of Gjirokastra

Tucked away at the top end of Sheshi Çerçiz Topulli (Square) in the old part of Gjirokastra is a small statue which you could easily miss. Next to the potted plants in front of the Tourist Information Office is a white stone statue, of the upper body, of two women. This is a representation of Bule Naipi and Persefoni Kokëdhima who were executed by the German Nazis in 1944. From that time they became known as the Hanged Women of Gjirokastra.

Both of the women were in their early twenties when their country was invaded by the Fascists and, like 6,000 other women (out of a Partisan force of 70,000) they decided to take up arms to drive the invaders from their land.

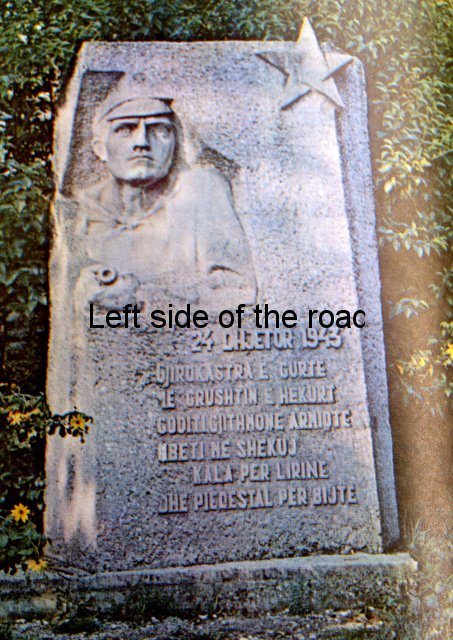

Bule was born in Gjirokastra town and apart from the statue in the main square she is referenced, as a ‘People’s Heroine’, on a monument in the Dunavat area of the town. She was a member of the youth group of which Qemal Stafa was the leader so it would seem that she had adopted the Communist ideology at an early age.

I’m not sure where Persefoni came from but apart from the monument to her death in Gjirokastra she is mentioned on the monuments in Qeparo Fushë (which is on the Adriatic coast), Kardhiq (in the mountains to the north-west of Gjirokastra) and Përmet (in a couple of valleys over to the east of Gjirokastra). This would seem to indicate she had been a Partisan for some time and had been involved in quite extensive sorties against the Fascists.

The exact circumstances of their capture I’m not aware but it seems they were captured at more or less the same time, imprisoned and then the German Nazis decided to make an example of these young and courageous women in an effort to deter others from opposing their occupation. These terror tactics are common in the history of imperialism.

A favoured tactic by the Nazis throughout Eastern Europe was the public hanging of those who had been fighting against them on being captured and, according to the statistics, this was even more common when women were concerned. The intense military opposition to the Fascist invasion in countries such as Albania and the Soviet Union meant that there are no pictures of women walking arm in arm with the German invaders in Tirana and Moscow (as you do in Paris). What we do get, however, are hundreds of pictures of young women hanging from the gallows in public squares.

These were not the executions that might take place in those countries where capital punishment was, or still is, the case. Everything was done by the Fascists to turn the occasion of the killing of an individual into a lesson in politics. There would be no, or very limited, process of law. Many of the executions were carried out summarily and even if there was the pretence of a trial the outcome was known before it had begun. Almost always they would be public executions, carried out in a main square, with the rest of the population forced to watch. Here the aim was to both strip the victims of their dignity and give that added spice to the terror instilled into the onlookers.

Neither was the execution the clinical affair that was eventually meted out to those German Fascists found guilty at the Nuremberg Tribunals of 1945-9. Those who were dealt with by Albert Pierrepoint would die in seconds. This would have been in ‘ideal’ circumstances. However, on the streets of Gjirokastra on July 17th 1944 Bule and Persefoni would have been stood on a stool under a low and flimsy gallows, with a thin piece of rope around their necks tied in a crude slip knot and then strangled to death when the stool was kicked away. As in the case of most of these lynchings the two women faced their fate with dignity and a continued hatred of the enemy. It was the practice of the Nazis to leave the bodies hanging for as long as possible to hammer home the message but as they were murdered in the summer they would have been cut down quite quickly. (This is just one of the reasons I am opposed to the German War Cemetery in the park behind the University in Tirana.)

The two young women were murdered in the square where the statue now stands.

Now the statue in Gjirokastra’s main square is not one of my favourite examples of Socialist sculpture. In fact I can think of no other I find less pleasing. I don’t yet know who was the sculptor but I don’t think it’s one of the best, or most appropriate of monuments, to two brave, young women.

They appear thin and haggard. Their faces are gaunt and their eyes seem to be bulging out of the sockets. The facial expression says nothing, unsmiling but not telling us anything else about how they might have been thinking. Compare this lack of expression with, for example, the statue to the Partisan in the centre of Tirana. He’s angry (sometimes I think a little bitter – and that’s something coming from someone who harbours a lot of anger) and you know that immediately you look at his face. You don’t get any emotion from this statue, not even a sensation of dignity. Also, there’s a problem with the location. It’s pushed to the edge of a car park, close to a building, as if it’s only there on sufferance (which it probably is) and doesn’t permit the viewer to consider the monument for what it represents.

But in a study of Socialist Realism these two Communist martyrs allow an analysis which has not been possible to date. Not only is there a statue in the location of their deaths but their fate has been represented in a number of media which suggest a number of interesting ideas.

As far as I’m concerned a better sculpture is one created by Odhise Paskali in 1974. This is called ‘The Two Heroines’, which I think is a better title than ‘The Hanged Women’. (Since I first came across this story and related art works I’ve always considered that there’s something cold and almost impersonal in referring to such courageous women in such a way. It seems to say that their short lives are determined solely by the manner in which they died.)

(The original of this statue is in the corridor of the old Gjirokaster Castle Prison. It was from this prison that the two women were led downhill to the main square of the old town for their public execution. It can be seen by going upstairs to the Armaments Museum – which has some interesting examples of Socialist realist Art (both paintings and sculptures). The entrance to the prison is off this part of the museum.)

This is more sympathetic to the situation. They look like young women and have determination etched on their faces. It’s a head a shoulders view of the two women and they are joined by their hair. By doing so it tends to go against reality as Persefoni was much taller than Bule but here they are on the same level. However much I consider this to be a better statue there is an important aspect which I think is bizarre. That is the addition of the noose around their necks.

Why? It again defines the women by their deaths. This is just crass Catholic Christian imagery and should have nothing to do with Socialist Realism. If you were to visit Catholic churches in Spain and Italy you would encounter countless paintings and images where the Christian martyr would be depicted alongside the cause of his/her death, normally with an enigmatic look on their face. I don’t understand why this should appear in the country to have declared itself an atheist state, as Albania did in Article 37 of the 1976 Constitution. This is why there’s always a need for a Cultural Revolution to monitor how the society and its history are being represented. ‘People’s Heroes/Heroines’ might be martyrs for the cause of independence and communism but there’s a fine line between that and the idea of Christian martyrs.

There’s another image that seems to follow the approach adopted by Paskali and that’s an engraving by Safo Marko.

This is a triptych. On the left is an image of Bule involved in a demonstration in her home town. As a member of the youth groups this is what she would have been doing before heading for the hills and joining the Partisans. On the right is an image of a female Partisan, armed and marching through the hills. This could represent either of the women. The problem comes with the central, bigger panel.

Here the two women are depicted, in chains, standing before a very large tree, two nooses hanging from one of the lower branches. This repeats the Christian idea of martyrs together with the instruments of their death but with the added problem of creating a ludicrous scenario. They were killed in the main square of an old fortress town built there because what was in abundance was a lot of stone. No way could such a tree exist in that environment. The scene suggests that the murder took place in the countryside.

Another engraving, this one more in the spirit of Socialist Realism, is by Lumturi Dhrami.

Here we know we are in Gjirokastra with the image of the castellated tower on the horizon and the cobbled streets along which the execution party is walking, downhill towards Sheshi Çerçiz Topulli. The two women are in the centre foreground, one in profile the other looking out of the picture. There’s determination on their faces. They know what is about to happen but there’s an impression of ‘so what?’.

They are surrounded by German soldiers but also in the picture are Albanian collaborators, these would have been members of the fascist-nationalist of Balli Kombëtar who allied with the ‘nation of Aryans’ as they shared similar racist and anti-progressive beliefs.

There are also two paintings I’ve seen depicting Persefoni and Bule. The first one I’ve yet to identify the painter and I’m sorry it’s such a fuzzy image.

What’s interesting about this painting is that I’ve seen photographs where the image was being used in classrooms to tell children about the event in 1944. This is not an exceptional painting (although I’ve only seen a poor reproduction) but is simple in that we have four individuals, the two restrained women and two Nazi guards taking them to their execution. The castle walls form part of the background and in the foreground we can see the bayonet of one of the invaders, the greyness of the soldiers uniforms in contrast to the colours (muted but colours nonetheless) of the women’s clothing.

The final image I’ve come across is a painting by Pavllo Moçi simply called ‘Persefoni and Bule’ which is in the collection of the Duress Art Gallery.

This depicts the two women in a prison cell, holding hands as the door of the cell is opened by the Nazi guards to take them to their death. Persefoni is on the left and has her right arm in a sling. Bule is standing defiantly with her legs slightly apart as if ready to fight against all odds. Light coming through the door shines on them, highlighting them against the gloom of the cell itself, with the guard in shadow, all demonstrating where the future lies.

On the walls they have scratched the letters VFLP representing “Vdekje Fashizmit – Liri Popullit!” (“Death to Fascism – Freedom to the People!”) which can be seen on the Heroic Peze monument, at the junction of the Tirana-Duress road, and the Peze War Memorial in the Peze Conference Memorial Park, among others.

The two women defiant to the end!

‘The Hanged Women’ – Gjirokaster (Andrew Andison)

The ‘renovation’ or ‘restoration’ of Socialist lapidars in Albania is, at best, a hit and miss affair. Often it just takes the form of a quick coat of whitewash over a monument to hide the ravages of time and the weather. This seems to have been the approach in Gjirokastra during the early part of 2017 – and the result can be seen above (thanks to Andrew for sending through a copy of his picture).

If there was no proper cleaning of the mould before the coat of paint was applied the statue will revert to it’s previous state soon after an Albanian winter.

Update November 2021

Currently the Çerçiz Topulli Square in the old town of Gjirokaster is being dug up and an underground car park is being constructed. This work will go well into 2022. As part of this work the statue of the Two Hanged Women (pictured at the head of the post) has been removed. It is not known whether it will return once the construction work is complete. It probably will as the present local government in Gjirokaster does seem to have a sense of history. It can only be hoped that when the statue returns it comes with an explanation of what it represents. Most Gjirokastrians won’t know the history, even less any visitors from other parts of Albania or the rest of the world.

Also I am adding here another painting representing the day of execution of the two young Partisans. Paintings from the Socialist Period of Albania’s past may not be on permanent exhibition but they are still (at least some of them) in public hands and in storage – although not always stored in the best of conditions.

This telling of the story is by the artist Guri Modhi (1921-1988) who also was the painter of ‘The Partisan Oath’ (1968) which has been part of the permanent exhibition of Socialist Realist Art in the National Art Gallery in Tirana for many years. (At present the gallery is displaying virtually everything from the store-rooms and it is not known what the permanent exhibition will be once this display comes to an end.) This was on display in the theatre in the centre of the new town on the occasion of the 75th Anniversary of the Liberation of the city on 18th September 1944.

One positive aspect of the location is that the two women are looking over towards the wall which forms part of the local government building. On this, picked out in large letters in relief, are the words ‘Lavdi Shqiperise’ – ‘Glory to Albania’ or ‘Long Live Albania’. Even though I had looked at this carefully it didn’t register that there’s something wrong. There’s a lack of symmetry. Why are the words so far apart and what is the ‘scar’ between them? It has been brought to my attention that the space (where someone has worked hard to obliterate what was there before) almost certainly contained the words ‘Partise se Punes e (Shqiperise)’, PPSH or the Party of Labour of Albania (PLA).

This is just another example of the vandalism that swept the country after the counter-revolution of 1990. The reactionaries still try to present themselves as patriots but if it were not for the Communists in the National Liberation Front in the war against fascism then the country would have only the sort of independence it has at present, that is, one where millions have to work abroad; foreign NATO troops crawl over the country like flies; local industry and agriculture is at a pre-capitalist stage; young Albanian women populate the brothels of Europe; and the country begs to be let into the ‘big boys’ club of the EU.

I’ve not come across this type of inscription (whether in its original or vandalised form) in any other town in Albania. It is partly obscured by trees and any vehicle that might be parked on that side of the square can block the view so it can be easily missed.