Tirana Catholic Church – The Last Supper

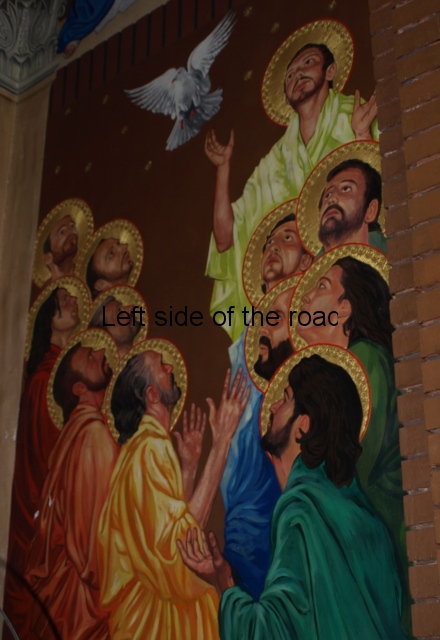

More on Albania ……

Sacred Heart Catholic Church in Tirana

Sacred Heart Catholic Church in Tirana displays new and interesting murals to replace the frescoes of the past.

Part of Albania’s ‘Cultural Revolution’ in the late 1960s took the form of a concerted attack upon organised religion, whether it be Islam, Orthodox or Catholic Christian. Apart from declaring Albania to be the world’s first atheist state both the infrastructure and the personnel of the different religions underwent radical changes.

Many of the previous religious buildings were converted to general use becoming cinemas, gymnasiums or places that could be utilised by the population as a whole. A significant number of the priesthood were subject to arrest and imprisonment for conspiring against the Socialist state and even though these accusations were denied at the time, both within and without the country, the manner in which some of these individuals have been rehabilitated and lionised by the present reactionary government proves the justified claims of the People’s Republic of Albania.

Since the decision of the Albanian people in the 1990s to destroy everything that had been constructed since the defeat of Fascism in 1944 after they had; finished being robbed by con men with their ‘get rich quick’ pyramid schemes; stopped killing each other for no apparent reason; emigrated from their country in their millions; they turned their attention (for some inexplicable reason) to what appeared to be the most pressing need of the time, i.e., the building or restoration of hundreds of religious buildings.

Any visitor who travels even a short distance in Albania cannot avoid noticing the number of new churches and mosques in virtually every village, town and city. The total destruction of the economy during the madness of the 1990s meant that the resources to pay for this could not have come from within the country itself, even less from the so-called ‘faithful’ who barely had enough to feed themselves.

The resources for all this building programme came from the oil rich feudal monarchies of the middle east (for the mosques), the gangsters of the erstwhile Soviet Union (for the Orthodox churches) and that centuries old bastion of reaction in Rome (for the Catholic churches).

Much of this money has been put into ‘prestige’ projects. The Catholic Cathedral of St Paul and the very recently opened Orthodox Resurrection of Christ Cathedral (Katedralja Ngjallja e Krishti), both in Tirana, are cases in point. Not a lot of this wealth has filtered down to maintain some of the, older, much smaller and more modest, historically important buildings that were placed on a list of structures that were part of the country’s heritage. Even at the height of the atheist campaign more and more of these buildings were being identified and protected yet the present day religious state is ignoring these as they have a very low profile, for example, the two ancient Orthodox churches in Old Himara or the Panagia Monastery Church, Dhermi in the south of the country.

The mosques follow very much a formula in their construction, both inside and out, and the decoration avoids any depiction of people or animals. The Orthodox churches are also formulaic, but in different way, with the icons of the saints that dominate the interior. It is in the Catholic churches, which are in the minority, that you encounter interesting, post-Communist paintings that tell (at least for me) a much more interesting story, a story which cannot be separated from the socialist period.

I’ve already written about the paintings in the Franciscan Church in Skhoder, in the north of the country, here I want to write about a Catholic church in Tirana.

This is the Sacred Heart church (Kisha Zemra e Krishtit), run by the Jesuits, in Rruga Kavajës, less than a kilometre from Skënderbeg Square in the centre of the city. This is the road that you would go along if you were to take the public bus to Kombinat, where you find the city’s main cemetery and the present location of Enver Hoxha’s grave (he’s not been allowed a lot of peace since his death).

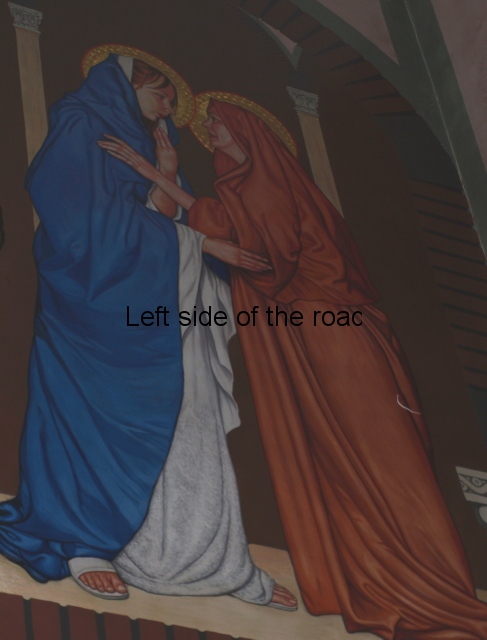

Previous frescoes were removed when the church was converted to a cinema in the late 1960s and new ones were completed in 1999 and the painter was Shpend Bengu (born 1962 in Tirana). The murals, although based upon traditional images seen in many Catholic churches throughout the world, have elements that are both interesting and slightly strange, if not to say unique, in Christian iconography. These murals are on either side of the altar.

On the left is a depiction of The Last Supper. This follows the ‘standard’ representations of this mythical event. Christ sits at the middle of the table and is the centre of attention. In front of him is a wine goblet and a chunk of bread – the origin of the Eucharist. The closest one to him, on his right, will be Peter. He has the typical short, curly (greying) hair and is the angry one – you can see he has his right fist tightly clenched. Fast asleep (has he drunk too much of the wine or is this a misreading of the event in the Gospels?) is John. The youngest, because he doesn’t have a beard, will be Philip or Thomas. The others could also possibly be recognised due to the tradition that has grown up over this image.

However, there are a couple of differences in this painting. Whilst all the others are concentrating on Christ one is looking into the distance, seemingly over our heads. Why? I don’t know and can’t even guess. We see the faces of 12 but there is one with his back to us – that is Judas. Traditionally he is depicted in a number of ways at the table. He is nearly always separate in some way, often looking away as if ashamed of what he has already done and is about to do. I’ve even see pictures where he has already left the table to carry out his dastardly deed of betrayal. Here he has his back to us.

Tirana Catholic Church – Judas

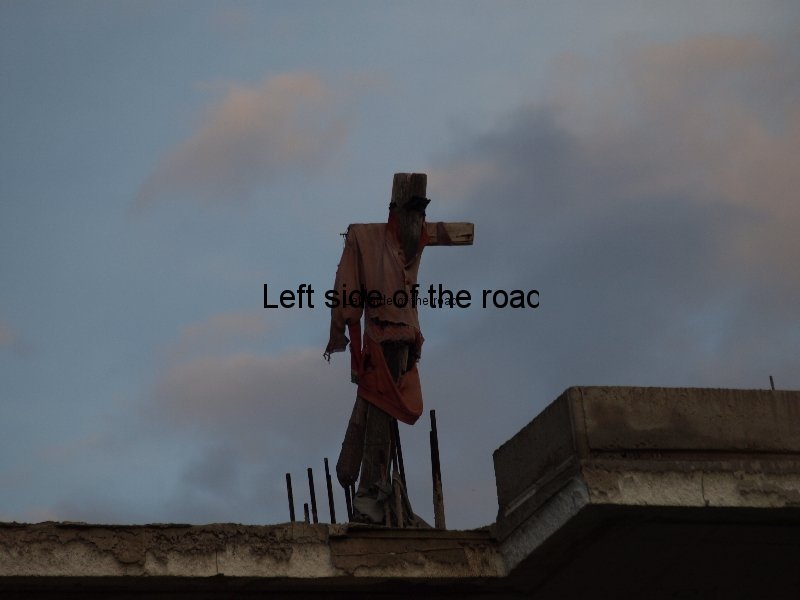

That’s not uncommon and might come from the Byzantine tradition of not having an ‘evil’ person looking out of a painting as they could, possibly, corrupt the viewer. This would very much feed into the local Albanian idea of the ‘evil eye’ that I write about in the post about the ‘dordolec’ and superstition in general in present day Albania. What is also interesting about this Judas is that whilst the others are dressed in fine, brightly coloured robes, he wears what looks like an animal fur, something rough, yet again separating him from the rest of the Saints. And, of course, he doesn’t have a halo.

All the faces also appear as if they are of real people. Many Last Supper images are idealised yet in this painting you could very likely meet these people in a present day Albanian bar or cafe, a realism that is rare, Caravaggio being the model for this type of representation. And notice the noses, they are long and straight, just like Albanians today, especially in the north of the country – that becomes relevant a bit later

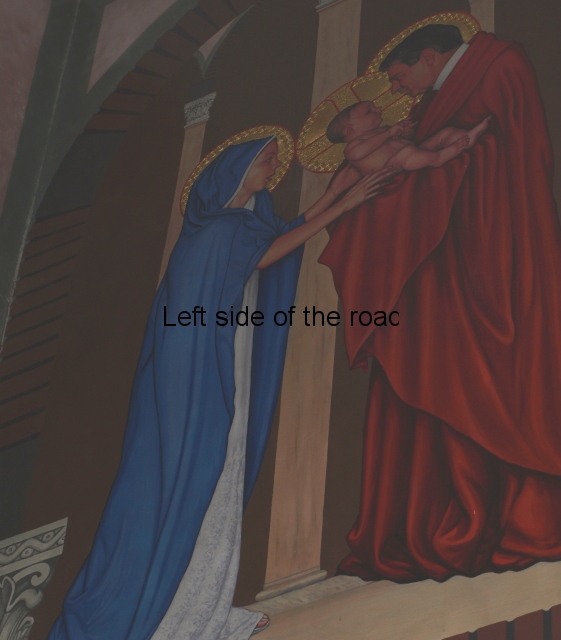

Tirana Catholic Church – Mary at the Crucifixion

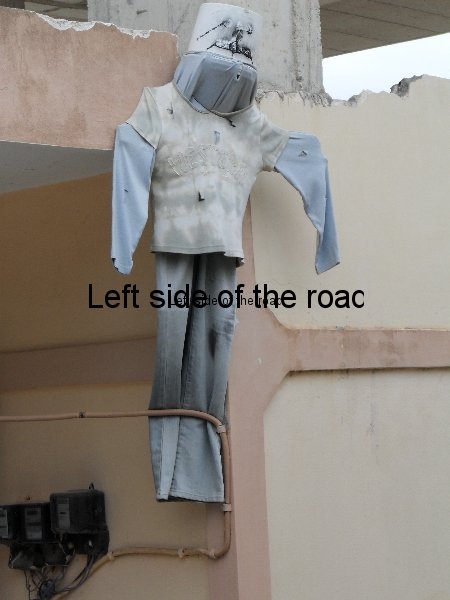

To the left of this painting there’s an image of the Crucifixion. This is very strange. Crouching at the base of the cross is Mary Magdalene. She is very often depicted with long flowing hair (often a redhead) and is also dressed in red. This encompasses the legend that she was a prostitute and the colour encourages thoughts of the ‘scarlet woman’ and it is also argued that this shows her love for Christ. But I’ve never seen a Mary wearing such a diaphanous cloak that she appears almost naked. Yes for nymphs of the forest – but not normally in a church. After all she’s supposed to be a ‘reformed’ prostitute.

Tirana Catholic Church – Mary Magdalene – detail

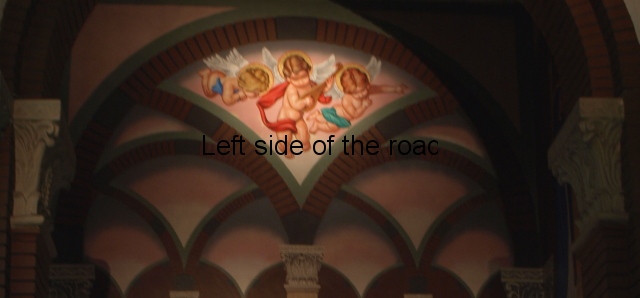

On the other side of the altar is a painting of The Annunciation, when the Archangel Gabriel appeared before Mary to tell her she was to bare the son of God. This again follows the normal, traditional format, but not completely. Mary has been reading a book (how such a poor woman would have got the resources to possess such a valuable commodity 2,000 years ago and one produced on a printing press that wasn’t invented for another 1,450 or so years is never explained); Gabriel carries a lily – this represents both Mary’s virginity as well as the idea that this all happened in the Spring – yet I’m not sure if the lily is a native plant of Palestine; and flying above is the Holy Spirit, represented by a dove, this one with a surprisingly bright red beak and feet.

Tirana Catholic Church – The Annunciation

But this painting is different from the norm in one particular way – the Archangel Gabriel here is obviously a very young woman, almost a contemporary of Mary. Often Gabriel can appear androgynous, especially in Renaissance paintings, but here her long flowing hair and facial features are unmistakeably female. For me that’s definitely a first.

And as in The Last Supper these are real people, you could imagine passing such women in the street, there’s no separateness, nothing special about them that identifies them as different from mere mortals. Mary definitely looks surprised, as anyone would be if they were told they were to be having a child without having known any sexual relationship, let alone it being the son of God.

Again look at the noses. These are typical Albanian noses. Whereas, especially in the north, many Albanians have a classic Roman nose, long and straight, also reasonably common is the small, turned up nose that you see in this mural.

For a religious painting I find it quite charming.

More on Albania …..