Seventh Assault Brigade – Sqepur

More on Albania ……

View of the world

Ukraine – what you’re not told

To the Seventh Assault Brigade – Sqepur

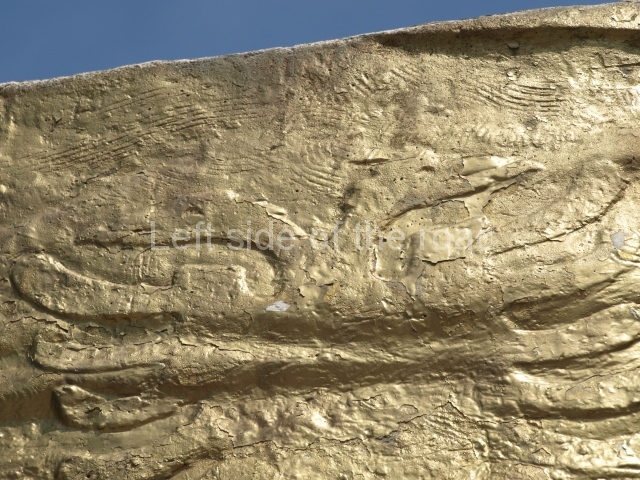

Time hasn’t been too kind to the lapidar to the Seventh Assault Brigade which is situated beside the main road between Fier and Berat in an place called Sqepur. It’s at the top of a hill and is relatively exposed to the elements and this has taken it’s toll on the plaster work. There seem to have been attempts to paint, ‘renovate’, the images over the years but as this has not been done professionally this has made the images and some of the text more indistinct, filling in spaces and taking away the finer detail.

The lapidar consists of a tall monolith in the shape of the end of a rifle barrel with a flag attached and a panel at 90 degrees to this monolith showing scenes of battle.

The idea of using a rifle as the monolith is not unique, it has been used in Mushqeta and Priske, for example, but this one is slightly different in that attached to it is a stylised representation of a flag, here painted red. Due to the records being destroyed in the 1990s and those pictures of lapidars that were published in couple of books being principally in black and white there is some question if most of the lapidars were originally in colour. For good or ill many have been painted subsequently, probably even during the Socialist period so in that way distorting the aim and intention of the artist and sculptor.

The idea of attaching a flag to a rifle is again something that can be seen on other lapidars, but normally when the rifle is being used as a temporary pole and the flag being waved by a Partisan. This is the case with the female Partisan in the Fier Martyrs’ Cemetery.

The image of the wooden butt of the gun is seen here as it flares out from the vertical at the very bottom left hand corner of the monument, below the panel with the images of fighting.

Joining the rifle and the flag pole, just above the horizontal panel are two wide, concrete bands. On the upper the words

Forcat partizane të ish-qarkut të Beratit are attached in relief,

this translates as

Partisan forces of the former district of Berat

The town of Berat being located only about 15 kilometres to the south-east.

On the lower band, in exactly the same font and manner the words;

Forcat partizane të Brigadës VII Sulmuese appear

this translates as

Partisan Forces of the VII Assault Brigade

The National Liberation Army was made up of a number of such Brigades, guerrilla groups originally but developing into more formal structures as the war progressed, more and more fighters joined and the power of the Fascist invaders was broken. These Brigades were made up from people, men and women, who lived in the area although as the war developed they would sometimes move to other parts of the country to satisfy the military needs at any time.

The spacing of these letters looks a little strange, especially the lower slogan, but it’s not really possible to make out if anything else would be there to necessitate such spacing.

On the left hand side of the lower panel we have images from a battle. On the extreme left is a Partisan, in full uniform, firing a sub machine gun downwards. His right foot is placed in front of him and his left leg behind him to provide stability on uneven ground. This is a common device, used in many monuments of the time, such as the star at Pishkash and the bas relief in Bajram Curri, to tell the story that the War of Liberation was one that was fought, and won, in the mountains and that much of the early fighting especially would have been surprise ambushes from up on high.

It’s not possible to see if there’s a star on his cap but we can make out a scarf flying from his neck so we can have a reasonable assumption that he’s a Communist. One unusual feature is that he seems to be wearing a greatcoat, the bottom end of it seen between his outstretched legs. This is something that hasn’t appeared on other lapidars, to my knowledge. Unfortunately, the very end of the gun is missing, there being quite a lot of small areas of plaster that have disappeared over the years.

Behind him is a standing fighter but who is dressed in civilian clothes, his open jacket flapping in the breeze with his movement. Around his waist can be made out four ammunition pouches.

Photographs of guerrilla groups of the time show a mix of uniformed Partisans as well as those in everyday clothing. (Why do left wing guerrilla groups, from wherever in the world from the 1940s onwards, keep on taking pictures of themselves? It’s OK if you win but these pictures will cause untold problems if they get in the hands of the enemy. Two of the worst disasters that came as a result of this obsession with photographing themselves was the case of Che Guevara’s ‘foco’ group in Bolivia in 1968 and the videoing of an inebriated Abimael Guzman, the leader of the revolutionary Communist Party of Peru – Sendero Luminoso, in Peru in 1991.)

This Partisan is not facing the action but is looking back over his shoulder, his right arm raised, his fist clenched, encouraging other, unseen, comrades to come and join the fight. His left arm is hanging down and he holds a rifle close to the bolt mechanism. The upraised right hand passes outside the main panel and he has lost all the fingers.

The third member of this group is another uniformed Partisan. His right foot is firmly placed on the ground and he is kneeing with his left leg. We see him from his left side and his right hand can be seen just above his left shoulder. It looks like he has just taken out the pin of a Mills bomb grenade with his teeth and is about to throw it at the enemy below. In his left hand he holds the top of a bag, the weight of which is resting on the ground, which looks like it’s full of stick grenades, so he’s well prepared for action. There’s evidence of a scarf around his neck so we are, again, to assume that he is a Communist.

Any facial detail on all three is very difficult to make out. In fact, any fine detail at all is almost impossible to see. To bring this monument up to a condition that it had when first unveiled would take a lot of work and money, an amount nobody would be prepared to pay.

Behind these three Partisans are five stars of varying sizes. They are cut into the panel (the images of the Partisans are in relief) and have been painted red. There doesn’t seem to be any pattern to their arrangement and are presumably there to represent Communism but there actual arrangement means nothing more to me.

The centre of the panel is yet another conundrum. Originally here was a lot of text, in relief, on this part. It looks like it was painted out and then a separate plaque placed on top – possibly with the same text, possibly with something completely different. This must have existed for some time as that rectangle is black from the mould that was created in the moist atmosphere behind the plaque. Now the plaque has gone and it’s possible to see some letters that were covered as well as those outside the area but it’s very difficult to make out the sense of what is there. It will need a good Albanian speaker (which, unfortunately, I’m not) to spend some time to unravel this puzzle. It is obviously something important as this text is in the central position on the monument.

The right hand side of the panel has a number of very strange, unusual and confusing elements. Basically what we have is the figure of an officer, we get that impression by the very nature of his uniform. (The National Liberation Army had a ‘traditional’ officer structure but after the success of the Albanian revolution that hierarchical structure was abandoned and the focus became much more on a people based militia rather than one based on ranks and superiority.)

Seventh Assault Brigade Officer – Sqepur

But all the proportions are wrong. His head is far too big for his body. When I first saw this lapidar I thought the artists had created a cartoon figure rather than a serious representation of a Partisan fighter, prepared to give his life for the freedom of his country. Having looked at it a number of times I’m also reminded of Stan Laurel.

His stance is also unusual. As part of his officers uniform he has straps that criss-cross his chest and around his waist there are ammunition pouches attached to his belt. Here we have him with the thumb of his left hand tucked behind these pouches in a very nonchalant manner. His right arm is hanging down but it’s not possible to work out what he might have had in that hand as this is another area where decay has had an impact on the image. There’s also some damage to the shin of his right leg. And the look on his face is a little bit weird. All in all not what you expect from an officer when there’s a battle raging close by.

It also looks as if the original design included a star which was to be behind this officer. The top point is above the rectangle of the panel, to the left of this officers head, but then the rest of the star just seems to disappear. It might be wear and tear but I can’t really work out why this star was placed where it was. It just doesn’t make much sense.

Apart from the neglect that the lapidar has undergone the whole area surrounding it is uncared for and dirty. The grass hasn’t been cut for years and the general area has an accumulation of rubbish and the ubiquitous flimsy plastic bags abound. The only living creature happy there (apart from me) on my visit was the stray dog taking shelter from the sun.

There is no known further information about the date of inauguration or the name of the artist.

Location

At a bend in the road, at the top of a rise just after passing the village of Sqepur when travelling from Fier.

GPS

N40.791619

E19.818821

DMS

40° 47′ 29.8284” N

19° 49′ 7.7556” E

Altitude

122.2 m

More on Albania ……

View of the world

Ukraine – what you’re not told