Proger – First Party Cell of PKSH

Proger – First Party Cell of the PKSH

The majority of the lapidars throughout Albania celebrate the events of the National War of Liberation and those who fought and died in that struggle. Others celebrate and commemorate events in the period of the construction of Socialism but there are few (probably a surprise to many) that are specifically devoted to the Communist Party of Albania (later the Party of Labour of Albania). One such – I only know of one other and that’s on the facade of the museum in Ersekë – is to the First Party Cell of the PKSH in the small village of Progër, close to Billisht and Korçë, not far from the border with Greece in the south-east of the country.

The lapidar consists of a huge, rectangular, concrete block on to which is attached a plaster bas-relief. This concrete mass is sitting on a plinth of large granite blocks. At the extreme left hand edge a large figure of a male partisan sits on a concrete plinth which is set out from the main block but the back of his body is attached to, and becomes part of, the main scenario.

We don’t see all the figure, he’s depicted from the thighs up. He’s staring straight out towards the viewer and his right arm is fully extended above his head, with the fist tightly clenched in a Communist salute. From the shoulder to just about the location of the thumb this arm is separate from the rest of the tableau. At the top of the hand he again becomes as one with the rest of the story.

He’s dressed in the full uniform of a Communist Partisan. This means he wears a cap with a star on the front and around his neck what would have been a red scarf, knotted at the front. He has two straps coming from his shoulders which cross in the middle of his chest. At the end of the strap that goes over his ammunition belt on his right hip hangs a small, cloth field equipment bag. The strap going down to the left, passes underneath the ammunition belt and this is attached to a revolver in its holster. We can see three ammunition pouches on this belt, each containing five bullets. Close to the equipment bag a Mills bomb hangs from a strap attached to the belt. In the space below where the straps cross it’s possible to make out the buttons on his jacket, The pockets on both sides of the jacket, over his breast, can also be seen. His left hand grips the top of the barrel of his rifle. Apart from the barrel we see nothing of his weapon and it looks as if the very top of the barrel has been broken off (a piece of the steel reinforcement sticking out of the plaster).

Immediately in front of his right thigh there’s an indistinguishable lump of plaster. It’s about the size of a football but I can’t think of what it could have been. The fact that it’s impossible to work out what it’s supposed to be suggests that this part of the statue has been the victim of vandalism.

Communist Partisan – Proger

Behind the Partisan’s head are the top three points of a five-pointed star. This suggests a religious comparison as it looks very much like a halo – one of those artistic references which come from previous artistic styles.

Above this star/halo is a larger star, its left most point reaching the left hand edge of the tableau. In the middle of this star are the letters PKSH. This stands for Partia Komuniste Shqiptare – Albanian Communist Party. This is the largest of all the stars on the lapidar. On either side of the uppermost point of the big star is a small star.

As we move towards the right we have two males, not in the uniform of a Partisan, but wearing the sort of clothes worn by workers in the 1940s. The first one is shown with his face in profile, as if he is speaking to his comrade. On his head he has a flat cap and is wearing a long overcoat. Hanging from his right shoulder is a strap and a bag of some sort appears to be at resting against his right thigh. It’s difficult to tell for definite but he seems to be wearing the long socks pulled up over his trousers – as is the case with the Partisan in the Korçë Martyrs’ Cemetery. He doesn’t appear to be armed in any way. His right arm is bent and his right hand is near the lapel of his coat, perhaps he’s making a point by using his hands to emphasise his argument. His left hand is resting on the shoulder of his comrade, an indication of their closeness and friendship.

Comrades – Proger

The next male is looking to his right, towards his companion, but we can see most of his face. He also has a flat cap on his head but his clothing is slightly different, although still workers clothes. He wears a short jacket and has extremely baggy trousers. On his feet he has the sandals common at the time. To give an indication of the detail we can make out the buckle on the belt around his waist. He is holding a rifle, half way along the length of the barrel, in his left hand – we can see most of the gun, only the end of the butt being hidden behind one of the other figures. Both these figures are standing on a ledge at roughly the level of the previously described uniformed Partisan’s elbow.

To the right of the head of this second male are three stars, a large one with a smaller one on either side. The left most point of the big star seems to overlap the smaller star on that side.

Below the stars, as if written on a wall, are the letters VFLP. These stand for ‘Vdekje Fashizmit – Liri Popullit!’ (‘Death to Fascism – Freedom to the People!’) – the common slogan of the Communist fighters and supporters. We have already seen these letters before, for example, on the lapidars in Peze.

The next figure is laden with symbolism and is the epitome of the Albanian Cultural Revolution of the 1960s/70s. This is of a female Partisan. Although not as large as the first male on the extreme left she is the central image on this lapidar. She’s virtually in the centre of the rectangle and carries with her the main symbols of the National Liberation War and the subsequent attempts to build Socialism.

The Spirit of Communism – Proger

She is shown as if she is running forward, her whole body giving the impression of movement. Her left arm is raised high over her head and is stretched out in front of her. She is gripping the short pole to which is attached the red flag of the Communist Partisans (and later, until the 1990s, to be the national flag of the country). She holds the pole just where the flag starts, the bottom end of the pole resting against her forearm. The flag itself streams out above and behind her head. On the flag is the double-headed eagle above which is a star. The folds in the material of the standard adds to the impression of movement. The very top inches of the flag protrude above the rectangle upon which the other images appear, slightly breaking the confines of the block.

The element of movement is also enhanced by the fact that her right arm is bent slightly behind her and in her hand she holds a Beretta Model 38 Sub-machine gun (seen before on the Drashovice Arch). Only one of her legs is seen and that is bent as she runs forward. Her face is in profile, just the right hand side seen, and she has her long hair tucked under her cap. This is an image seen before on the monument to the 68 Girls of Fier, amongst others. She’s dressed in the full uniform of a Communist Partisan and that means a star on her cap and a ‘red’ neck chief, stressing her political allegiance.

This centrality of an armed female is a fundamental of works of Socialist Realism of the period, clearly seen on the most well-known image of the mosaic on the façade of the Historical Museum in Tirana.

Below her is a male partisan with his right knee on the ground, in the act of firing his bolt-action rifle. He has the rifle butt up to his right shoulder and it’s possible to make out a star cut into the wood of the butt, a tradition from early independence struggles which was carried over to the war of 1939-44. He is also in full uniform, wearing a cap with the Communist star. There are puttees on his shins. These were (and versions still are) worn to protect the legs from damage in the rough terrain of the Albanian mountains. His feet rest on top of the letters that run from left to right along most of the bottom edge of the sculpture.

This takes us to about two-thirds of the way along the monument and here we have an actual physical line of division. This line runs from the wrist of the female partisan holding the flag to just before the left toe of the boot of the kneeling male partisan (the top of the line ‘hidden’ behind the fluttering flag). But I’m not too sure why.

All the images on the left depict the story prior to victory over the invading Fascists in November 1944. If the section on the right was to depict events after Liberation it would make sense, but that doesn’t seem to be the case. My doubts stem from the next image.

With his right foot resting on top of the letters at the bottom of the rectangle we have a large, older male. Here we don’t have the representation of a worker but of someone from the countryside. He wears a cap similar to the two workers who are having a discussion but the rest of his clothing, and his look, is more of a peasant than a town dweller. First, he has a bushy moustache, which was becoming rare in the towns. Secondly, his jacket looks home-made, two straps keeping what, I assume, is a leather jerkin closed at his chest. He wears baggy trousers with gaiters buttoned over his shin, more common and usual before the use of puttees (which were mainly for military use). His right foot is on solid ground but his left is on some sort of man-made walk way in the hills – an image I haven’t seen before.

He’s very muscular, as he has to be in order to lift the huge rock he has in both hands, his arms straight as they strain to take the weight. But why is he moving this rock? What prompts the question is that he has the top of the barrel of a rifle sticking up behind his right shoulder. Without the rifle it could be argued that he is building a wall or clearing a patch of land for cultivation. But if that was the case why does he need his rifle? This area is very close to the Greek border and there were incursions into Albania by British and American supported monarcho-fascists in the early days of Socialist Albania. There’s a monument to one such repulsed encounter in the town of Bilisht, only about 5 kilometres away (as the crow flies), on 2nd August 1949. That would explain why people were vigilant and keeping arms to hand but not necessarily on their person at all times when doing hard, physical labour in the countryside.

However, there is an image very similar depicted in a painting by Sali Shijaku, called ‘Skenderbeu’s Artillery’ (1968), where a huge rock has been moved to a high vantage point to drop on any invader. (Shijaku also painted the image, which is in the National Art Gallery in Tirana, of the last moments of Vojo Kushi.)

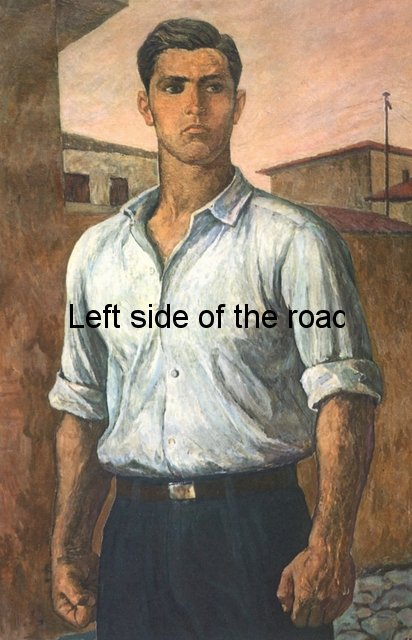

Skenderbeu’s Artillery, Sali Shijaku, 1968

So I’m uncertain of how exactly to interpret this image.

Because the final figure on the lapidar is definitely representing the new Albania after Liberation. Here we have a true Amazon. It’s the image of a country woman, facing straight out, her feet apart, and holding a large sheaf of wheat above her head, with both arms bent at the elbows. She’s a young woman with long hair hanging down both sides of her head and wears a long, simple peasant dress reaching half way down her shins. There looks to be a simple cord pulling it in at her waist. There’s a similar representation of a peasant women in the large sculpture called ‘Toka Jonë – Our Land’ (by Perikli Çuli, 1987) in the centre of Lushnje.

Building Socialism – Proger

If you look at the two peasant figures together it appears that the older man is bringing the young woman a huge rock but although I’m sure she could lift it I really don’t see the connection between them.

At the very bottom of the lapidar is the written explanation for the monument. Starting immediately to the right of the large male Partisan on the extreme left are the words:

‘Më 21 XI 1941 në fshatin Progër u krijua celula e parë e partisë në zonë [n e …]’

Which translates as:

‘On 21 XI 1941, in the village of Progër, the first Party cells were established in the area [n…e…]’.

(This was very soon after the establishment of the Communist Party of Albania in Tirana.)

The last words have been totally obliterated and, so far, I’ve been unable to find information on what is missing. Someone has tried to plaster over the remaining words but that vandalism hasn’t been that serious and they can still be read.

This is the first time I’ve seen a lapidar where the target of vandalism has been the written text. Normally it’s the stars that bear the brunt of the hatred.

The sculptor is unknown, as is the date of its inauguration, although often the unveiling of story-telling lapidars would coincide with an anniversary of the event being celebrated. Very often a local sculptor would receive the commission but Progër is still today a small village so the sculptor might have come from further afield.

Apart from the actual vandalism to the text the lapidar shows some signs of damage, The nose of the young woman with the sheaf looks broken and there are a couple of other places where damage doesn’t look like the result of time or general neglect. Unlike many places this monument hasn’t received a recent coat of paint, whether by design or just waiting to get some attention is unclear – local politics playing a role in this.

Although not unique there’s a fence with a locked gate to limit access from the road, necessitating a little bit of climbing and a short walk over rough ground in order to get close.

There used to be many small museums throughout the country during the Socialist period, with virtually all the Martyrs’ Cemeteries having at least a room where artefacts were displayed. In addition most towns would have a small, local museum. There are few remaining. Most were looted or vandalised during the early days of the reaction and now they are few and far between – although the recent renovation of the City Museum of Fier might be the start of a general move to recognise and remember the past.

Museum – Proger

In tiny Progër there was a museum just to the left and above the lapidar. It is no longer a museum but has, at least, been put to constructive use as it is now a small polyclinic – although the word ‘Muzeu’ can still be seen, in large letters, above the main entrance.

For such a small village Progër is home to two other lapidars, one commemorating the opening of the first school in 1908 and another to those from the village who fell in the National War of Liberation.

Location:

Progër is a small village 3 kilometres to the east of the road from Korçë to Bilisht.

GPS:

40.69477499

20.94036503

DMS:

40° 41′ 41.1900” N

20° 56′ 25.3141” E

Altitude:

844.7 m