Izamal

Izamal – Yucatan

Location

This is situated in the north of the state of Yucatan, some 72 km west of Merida on federal road 180 leading to Cancun. When you reach the town of Hoctun, take the turn-off to Izamal. The archaeological site is located in the city of Izamal and is open Monday to Sunday from 9 am to 5 pm. It has restaurants, hotels, toilet facilities and an arts and crafts centre where you can purchase objects made locally as well as in other Mexican states. The structures open to visitors are the K’inich Kak Moo, Itzamatul, Conejo and Habuc, as well as the Monastery of San Antonio de Padua, built on top of the pre-Hispanic platform known as Ppap Hoi Chak.

History of the explorations

Chroniclers from the 16th and 17th centuries were the first people to describe the constructions at Izamal and propose the first hypotheses about the functions of the different buildings. In the mid-16th century, Bishop Landa mentioned 11 or 12 constructions, one of which was used to build the Franciscan monastery of San Antonio de Padua. In the chapter on the constructions in Yucatan, his description of the K’inich Kak Moo building matches exactly the characteristics of the ruins found during the excavations. After the Great Pyramid of Cholula in Puebla and the Pyramid of the Sun at Teotihuacan, this is probably the third largest construction in the whole of Mesoamerica. Another important structure at this site is the Kabul, which the Franciscan chronicler Lizana mentioned in the 17th century. During the 19th century, some of the travellers who reached Yucatan visited Izamal and the Kabul caught their attention. John L. Stephens was the first to mention this building and a splendid stucco mask which was visible at the time and which Catherwood drew to illustrate the work of the famous traveller. Several years later, Desire Charnay recorded the stucco decoration on this building in greater detail, but unfortunately the ornamentation has not stood the test of time. The more recent archaeological research commenced in the 1960s, when Victor Segovia Pinto excavated part of the K’inich Kak Moo and a section of the Municipal Palace platform. In the following decade, the archaeologist Ruben Maldonado Cardenas conducted prospections along the Izamal-Ake causeway and at the Chaltun Ha building; he also performed archaeological rescue work at the place now occupied by the long-distance bus terminal. Soon after, Charles L. Lincoln drew up the first map of Izamal, or the area now occupied by the urban sprawl, but included only the most visible monumental buildings. The Izamal Archaeological Project was launched in 1992 with the mission of studying and preserving this important site, its architecture and the materials associated with the buildings. For over a decade, the most relevant buildings, such as the K’inich Kak Moo, Itzamatul and Habuc, have been researched and restored, as well as other lesser constructions such as Chaltun Ha, El Conejo and a section of the causeway leading to the Ake ruins. The project has involved a variety of experts, mainly archaeologists and restorers, who have undertaken different aspects of the research, such as prospections, the study of the settlement pattern and the architecture, and the analysis of the ceramic, lithic and malacological materials. Thanks to these efforts, we have now been able to interpret part of the cultural history of Izamal and make conclusions about some of the daily activities conducted by the people of the ancient city to survive as a polity and a regional economic centre. The project continues to this day with the restoration of the K’inich Kak Moo and Habuc buildings, as well as surveys of the Ah Kin Chel region in the search for more information about the sites associated with this metropolis.

Pre-Hispanic history

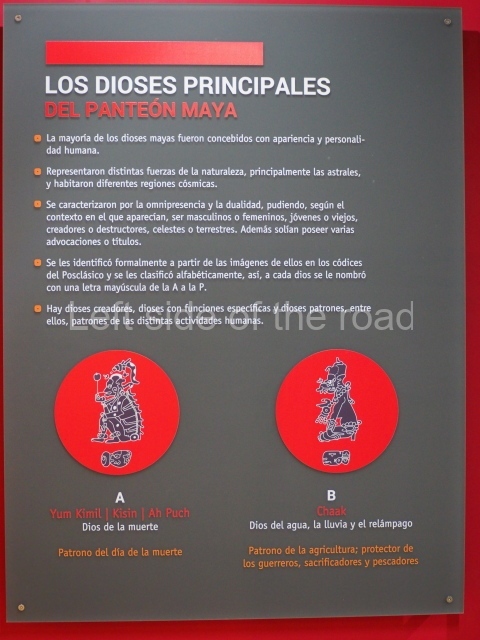

The earliest evidence of occupation found at Izamal corresponds to the Middle Preclassic (700-450 BC), when the urban planning process probably commenced. Between the Late Preclassic (450-150 BC), Protoclassic (150 BC-AD 250/300) and Early Classic (AD 250/300- 600), there was a great emphasis on construction, and the site became the most important centre in a large section of northern Yucatan plains. In the Late Classic (AD 600-800), the city gradually entered a decline, and during the Terminal Classic (AD 800-1000) and Early Postclassic (AD 1000-1200) it was controlled by another polity. By the Late Postclassic (AD 1200- 1550), it had been semi-abandoned, although it still retained its religious importance, and in the colonial period it regained its status as a densely populated city and remains so to this day. The pre-Hispanic settlement is regarded as a first-class site, on a par with others such as Chichen Itza and Uxmal, which also have monumental, albeit smaller, buildings. Recent research has confirmed that the urban area dating from the pre-Hispanic period covered over 50 sq km and was therefore 12 times larger than the modern-day city. In addition to important archaeological monuments, such as the K’inich Kak Moo – the largest in the Yucatan Peninsula – the present-day city also boasts numerous colonial buildings, including one of the finest monasteries built by the Franciscan order in Yucatan. Due to the fact that the colonial city was built on the pre-Hispanic site, much of the ancient settlement was destroyed. Nevertheless, it is still possible to see the large buildings in the city centre and numerous pre-Hispanic platforms in the adjacent area that look like hills. Because of this, Izamal is known as the City of the Hills, and in the past the people worshipped an idol called Itzamna, who under the names of Zamna and Itzamatul, the creator and benefactor of the Maya, was venerated in two of the main buildings in the central plaza of the site.

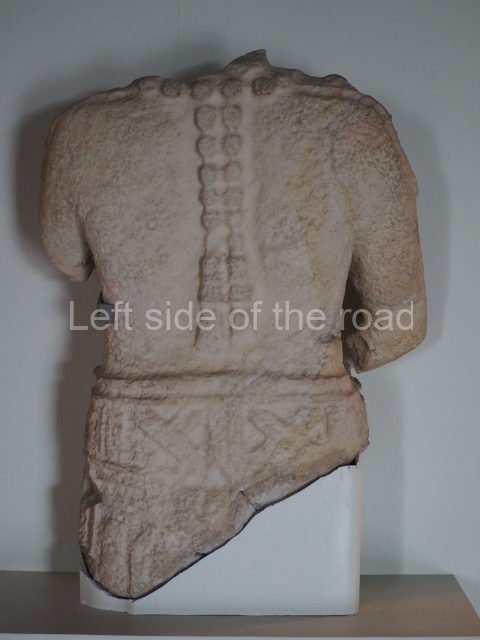

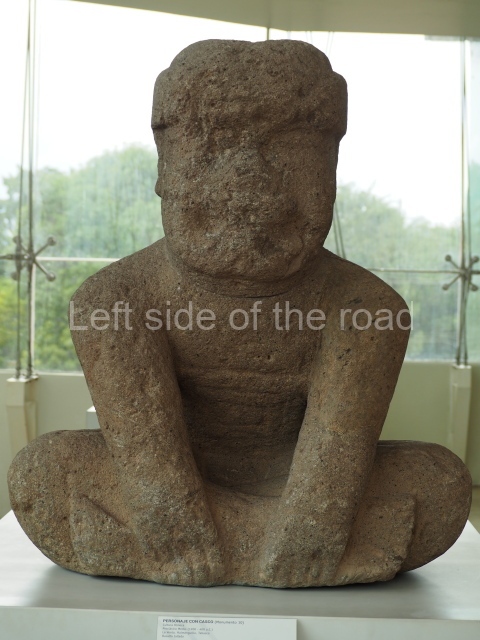

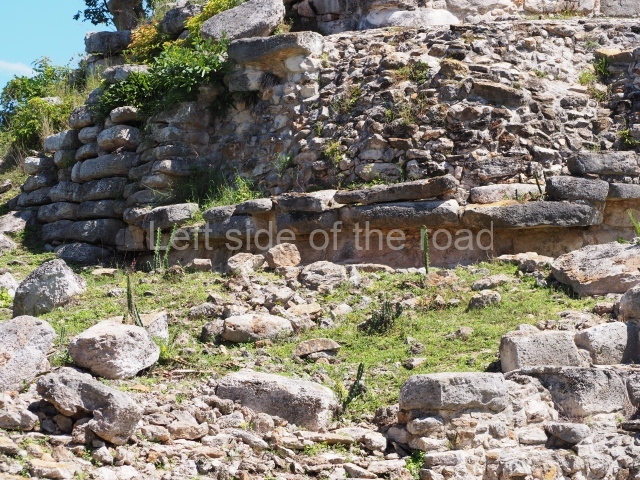

The site has a long sequence of development and over 2,500 years of occupation, stretching from the Middle Preclassic to the present day. The main activity during the pre-Hispanic period would appear to correspond to the Protoclassic and Early and Late Classic, which coincided with the construction of the most important buildings. These display a type of architecture known as the Megalithic style, which is differentiated from other types of construction by, among other things, the considerable size of the blocks of stone used. These architectural traits can be found in a wide area of northern Yucatan. This city also boasted an extensive network of causeways, demonstrating the complex level of social organisation attained by Izamal as the principal centre of an important region in the north of the peninsula.

It was precisely during this period of more intense activity that the settlement achieved its largest form and monumentality, reflecting the presence of numerous small sites situated on the fringes, initially with a certain degree of autonomy in relation to the central site, which as they were absorbed by the metropolis became more dependent on a centralised political and economic power. The existence of these peripheral sites indicates a population growth, which is manifested in the increased density of domestic constructions over a large area, amid the public buildings and the residences of the ruling class. The continual destructions that the archaeological site has undergone over the centuries have left very little information about the social stratum that governed the pre-Hispanic city and surrounding district, and about its possible relations with the governors of other cities. To date, we still lack sufficient information to be able to confirm that some of the burials found in the core area of the site correspond to one or other of the ruling dynasties. Neither have any stelae or objects with graphic or written information about this elite class been found. The historical sources all refer to a period subsequent to the construction of the great structures and causeway network, when the capital of the region known as Ah Kin Chel during the period of the Spanish Conquest was no longer this great metropolis. Thanks to various surface surveys, it has been possible to corroborate the existence of two important construction periods in the entire region. The first one corresponds to the Megalithic architecture and the heyday of Izamal as the regional capital, begun in the Late Preclassic and continuing throughout the Early Classic, while by second period, the Terminal Classic and Early Postclassic, that architecture had been virtually destroyed and had adopted the name of the Puuc style; the presence of this type of architecture indicates that there was more than a simple trading contact between different polities during this period, and even suggests the subjugation of numerous settlements to a single governing centre based at Chichen Itza. Although Izamal suffered more than 450 years of constant destruction, it is still possible to see enormous residential constructions inside the urban area. Most of them have been damaged by the subsequent construction of streets, the massive extraction of stones and intense looting. Even so, 163 buildings have been recorded inside the urban area of the present-day city. The archaeological map reveals a series of large plazas adjacent to the main plaza. The presence and distribution of other lesser constructions indicates that there were various open spaces delimited by the same structures still visible today. Izamal entered a decline in the Late Classic, almost certainly influenced by the growing importance of the Itza people, based at Chichen Itza, because according to the historical sources the site was conquered by Kak u’Pakal, one of the governors of that city. At the time of the Spanish Conquest, the main buildings had been abandoned – although we know that there were small hamlets around the core area ruled by Ah Kin Chel – but Izamal remained an important centre of worship for the Maya, which is why the Spanish conquerors chose this place to establish their presence. Izamal offers visitors a journey through various periods of the past and the chance to gain a greater appreciation of the Yucatec Maya culture.

Site description

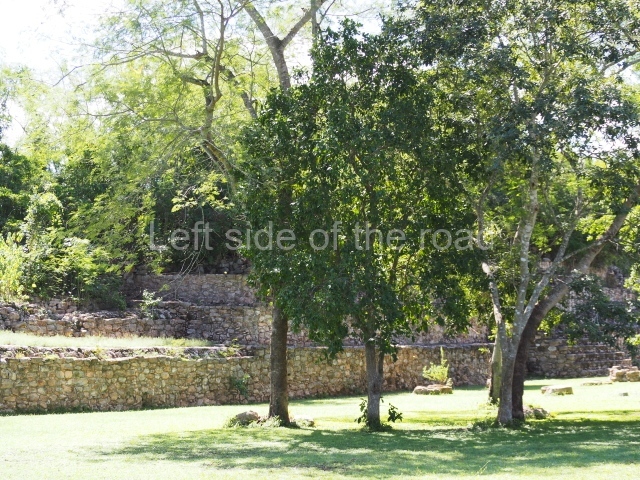

The civic-ceremonial precinct of Izamal is one of the largest in the Maya lowlands because altogether its buildings exceed one million cubic metres. It consists of a series of adjacent plazas. The main one is delimited to the north by the K’inich Kak Moo, to the south by the Ppap Hoi Chak, to the east by the Itzamatul and to the west by the Kabul. A secondary plaza is situated to the west and south of the Ppap Hoi Chak and Kabul, respectively, and then sealed by the Hun Pik Tok building and the platform on which the Municipal Palace was built. A third plaza, to the south of the main one, is delimited to the north by the Itzamatul and to the west by the Ppap Hoi Chak, while the south side is sealed by the building known as the Fundacion, which has not been excavated. Situated around these plazas are residential structures such as the Habuc and Conejo, which have been the focus of recent archaeological research. On the fringe of the city are various residential groups with their own monumental complexes, as in the case of Chaltun Ha, which was linked to the core area of the site by an internal causeway.

K’inich Kak Moo.

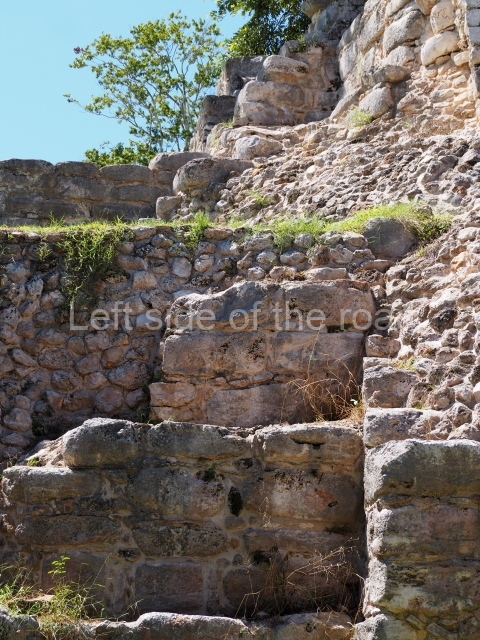

This platform adopts a fairly rectangular plan with the main axis more or less oriented to the north, and six stairways leading to the top platform. It consists of a large terrace that surrounds most of the platform, with a slightly sloping wall; situated on this terrace is another large volume consisting of a sloping wall and apron moulding, which together rise to a height of 10 m. On a second terrace there was once a vertical wall rising to the top tier of the platform, 17 m above ground level. The four corners of the platform are rounded but not inset, in keeping with other buildings at the site. The stairway on the south side is the largest, comprising two flights of steps. On the top platform is a building with nine tiers and a stairway with small balustrades. The steps are made of small stones, corresponding to the Puuc architecture.

Itzamatul.

This is the second largest and the second most important construction at the site, after the K’inich Kak Moo. The archaeological information obtained to date indicates three construction phases. The first was characterised by an almost square-plan building, consisting of various stepped tiers with sloping walls and inset, rounded corners, typical of the early buildings, rising to a height of just over 20 m from ground level; it displayed four access stairways, one on each side of the structure, of which nothing remains. During the second period, this early structure was covered, although the tiers were maintained and the sloping walls replaced by vertical walls with right-angled corners; access was restricted to the west side, overlooking the main plaza. The final modification occurred when a large platform was built over the earlier constructions; the access to this structure was via a stairway on the south side, part of which has survived to this day.

Kabul.

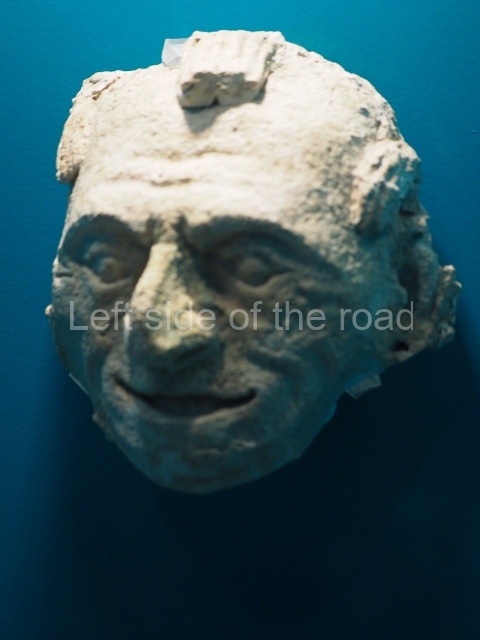

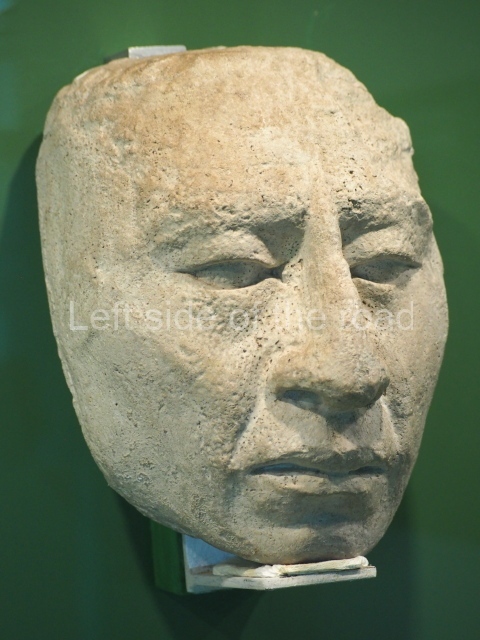

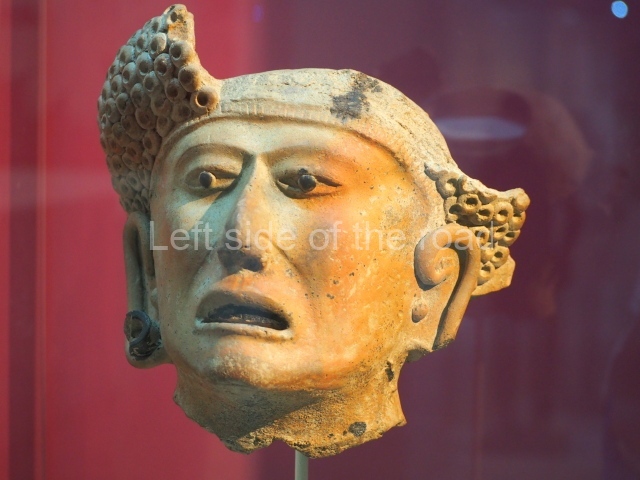

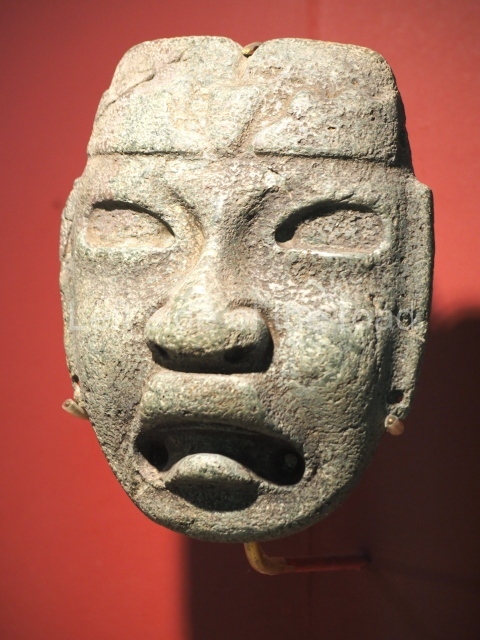

This building is situated in the courtyard of the Izamal Arts and Crafts Centre, where it is still possible to see part of the platform wall. The structure has not been restored, although in the past, according to travellers such as J. L. Stephens and D. Charnay, the building had an elaborate decorative repertoire with modelled stucco reliefs, principally in the form of masks dedicated to the sun god.

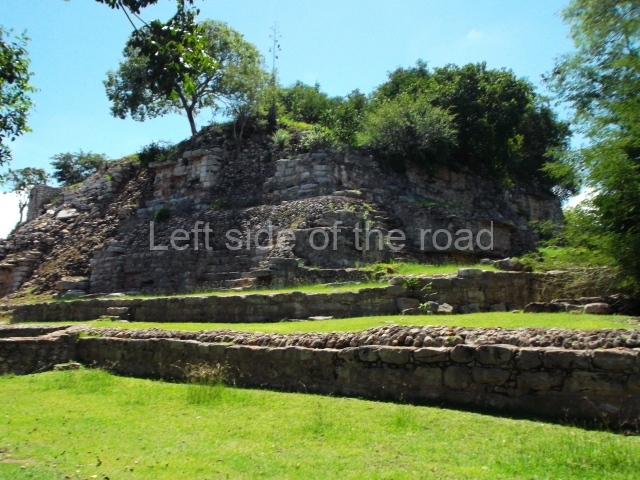

Conejo.

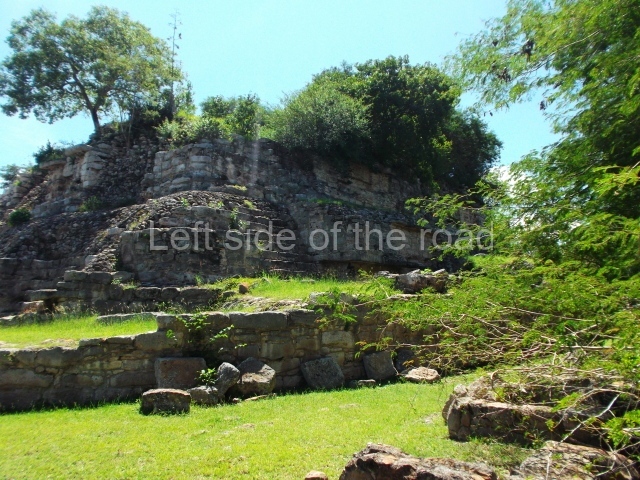

This is a residential platform in the east part of the city. The archaeological evidence uncovered to date demonstrates three construction phases. The walls are characterised by megalithic stones which during the original construction phase formed vertical walls with right-angled corners. In the subsequent construction phases, the walls adopted a slight gradient and rounded corners.

Habuc.

This is a two-tier structure: the lower tier consists of a platform measuring approximately 90×90 m and standing 3.80 m above ground level. The access is via a megalithic stairway on the west side. Situated on top of this large platform is a series of buildings distributed on three of its sides, forming a plaza. Over the years, these structures have been modified on several occasions and are currently undergoing restoration.

Chaltun Ha.

Situated south-east of Izamal, this is one of the fringe sites and contains a residential group with monumental architecture. The platform is more or less square-plan and surmounted by a temple. This must have comprised several lower tiers, of which only the first has survived. The building displays apron moulding and rounded, slightly inset corners. There is a single stairway on the north side of the building. It is currently undergoing restoration.

Path network.

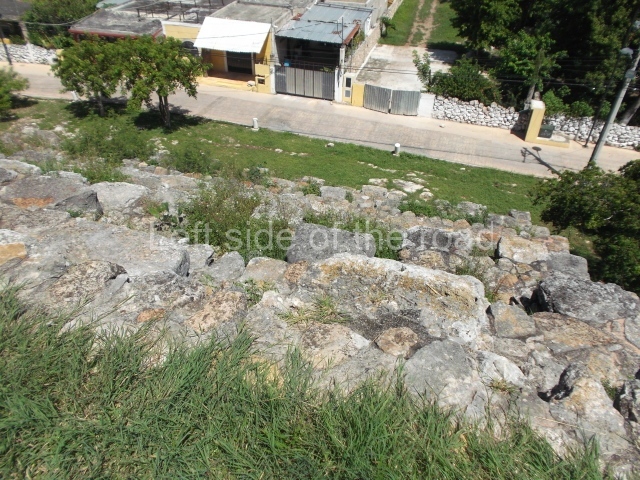

During the Early Classic, the causeway network between Izamal and Ake and Kantunil formed a socio-political unit and may well have also incorporated the Ud-Cansahcab network based on the fact that these cities display the same architectural characteristics. On the fringes of the modern town, it is possible to see where various long paths commenced, such as the one linking Izamal to the Ake ruins 29 km further west, and the causeway leading to Kantunil, 18 km to the south. Although four causeways have been mentioned in the past, leading to each of the cardinal points, nowadays only two of them are visible. We do know that there is a fairly dense residential area on the edges of the causeway leading to Ake.

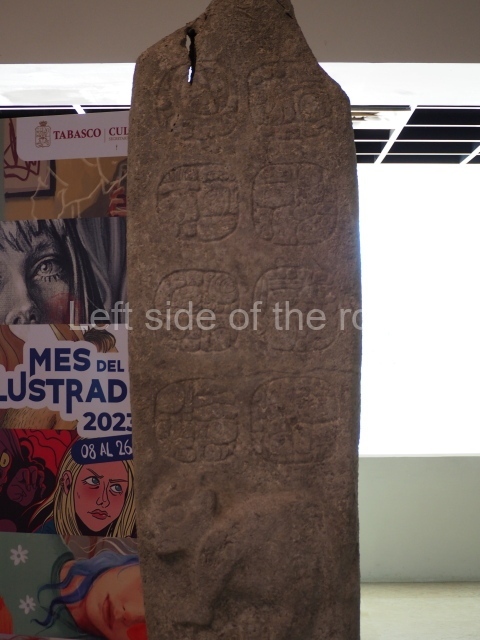

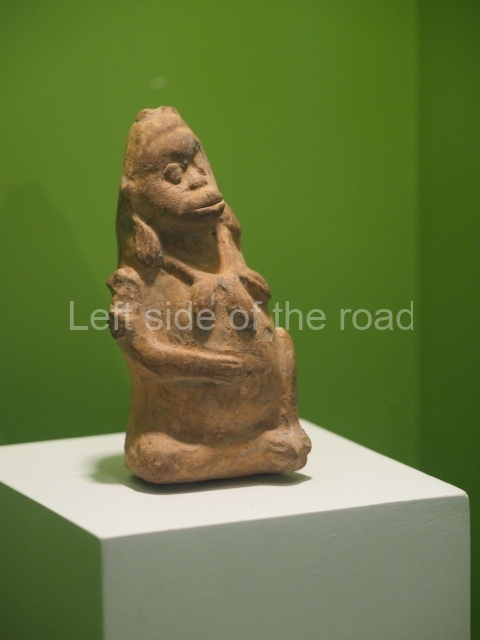

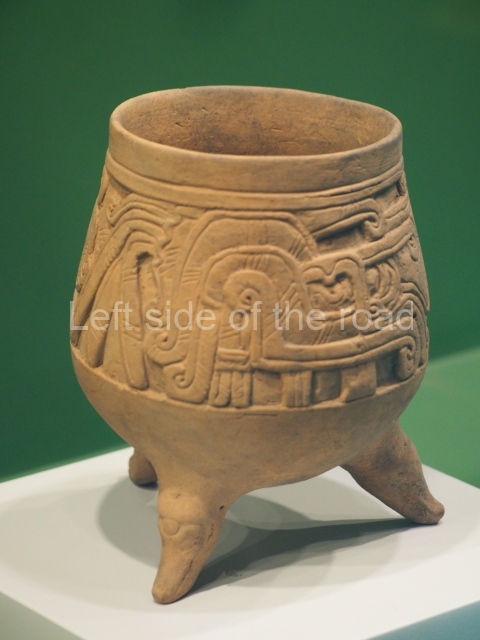

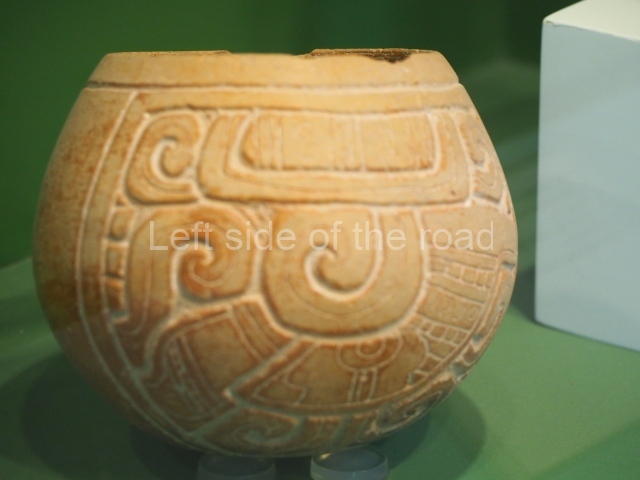

Ceramics

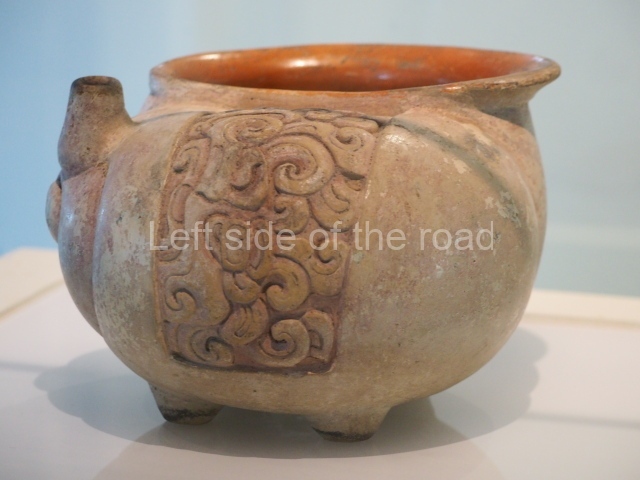

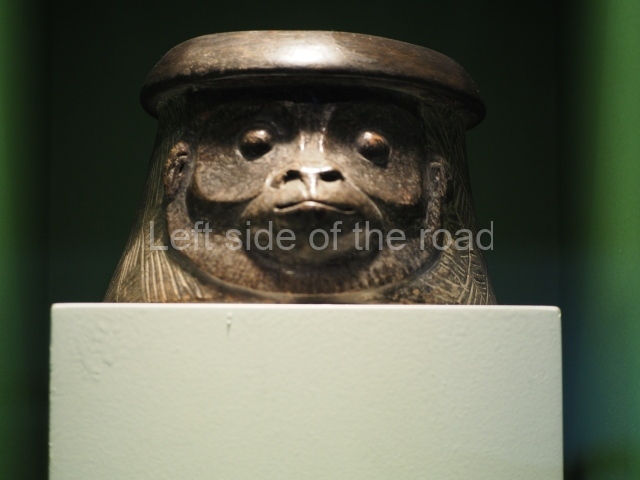

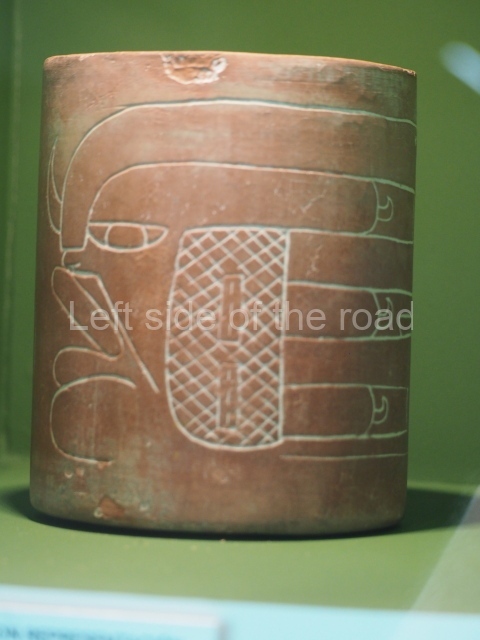

The analysis of the ceramic materials reveals a large quantity of forms and finishes such as striated, unslipped pots for domestic use, plates, dishes, bowls and vases, which are sometimes monochrome and sometimes bichrome or polychrome. These recipients were not only used in routine activities, such as cooking, storing food and as tableware – they also had ritual functions. The technological changes reflected in the ceramic materials indicate that during the Preclassic pottery had a wax finish, while in the Classic period it usually had a shiny finish.

Rafael Burgos Villanueva, Miguel Covarrubias Reyna and Luis Millet Camara

From: ‘The Maya: an architectural and landscape guide’, produced jointly by the Junta de Andulacia and the Universidad Autonoma de Mexico, 2010, pp 394-397

How to get there:

From Merida. Combis leave, when full, from Calle 50, between 63 and 65. M$35 each way. Takes just over an hour. The archaeological site is about 10/15 minutes walk from the main square. The official entrance to the site is in Calle 27.

GPS:

20d 56′ 12″ N

89d 01′ 00″ W

Entrance:

Free