More on the Maya

Uaxactun – Guatemala

Location

Uaxactun is accessed via a dirt track from Tikal and the journey takes approximately 45 minutes. The distance is 24 km and the track is passable, but a four-wheel-drive vehicle is recommended during the rainy season. There is also a daily bus to Uaxactun. The site is divided into two parts by the houses of the modern village and the visit lasts several hours.

History of the explorations

At the beginning of the 20th century, the place was known as San Leandro and Bambonal by the local rubber tappers. Its name changed to Uaxactun following its discovery by the Mayanist Sylvanus G. Morley on the morning of 5 February 1916. That same day Morley discovered Stela 9 and on deciphering the date of the stone realised that it began with the sign for Baktun 8, which in the Gregorian calendar corresponds to the year 327 BC, making it the oldest sculpted monument discovered to that date. In honour of this stela, Morley decided that the site should be named Uaxactun, which literally means ‘stone 8’. Recent epigraphic studies have revealed that the original name of the city was Sian Kan and that it enjoyed great prestige due to its antiquity and ancestry.

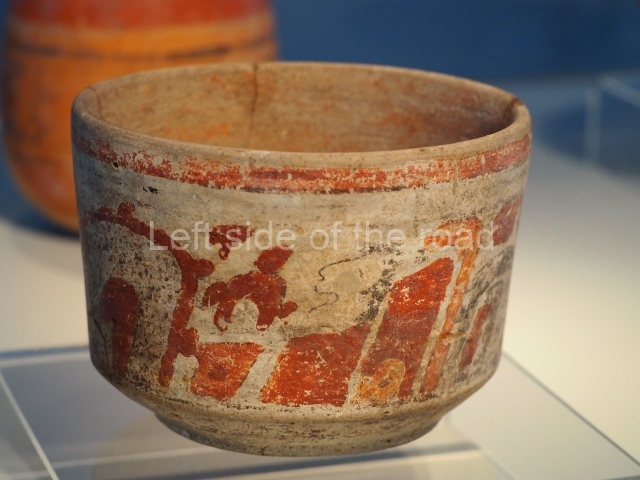

Uaxactun is one of the most important Maya archaeological sites as it was the among the first to be investigated and laid down a series of guidelines for future explorations. The ceramic spheres defined at Uaxactun continue to be used to establish the timeline and culture of the main periods into which the history of the lowlands is divided. It was here that the Carnegie Institution in Washington detected the first observatory in the 1920s. Such observatories are known as Group E complexes in honour of the discovery of this structure in Group E at Uaxactun. They are also known as astronomical complexes because they were used to observe the sun’s cycle, enabling the ancient Maya to understand the seasons, define solstices and equinoxes, perfect the calendar and predict the arrival of the rainy season. The first explorations were conducted between 1926 and 1937 by Oliver Ricketson and Ledyard Smith of the Carnegie Institution in Washington. The second project was undertaken by Guatemalan archaeologists between 1983 and 1986, led by Juan Antonio Valdes of the Tikal National Project; during this campaign, 11 buildings were restored and are now visible in groups A, B and E. In the meantime, around 1970, Edwin Shook and Enrique Monterroso had renovated the famous structure E-7-Sub.

Site description

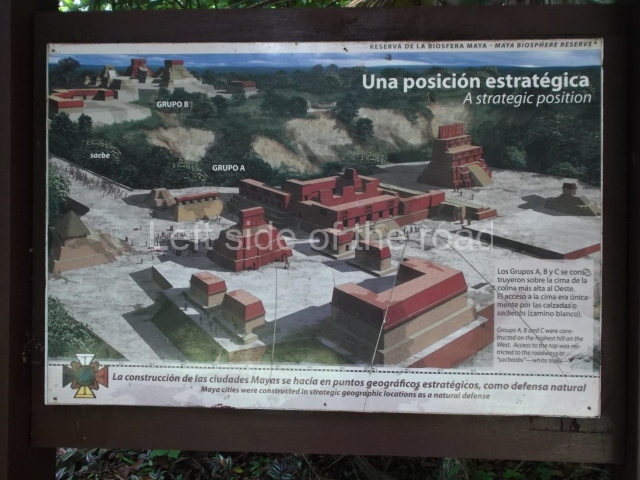

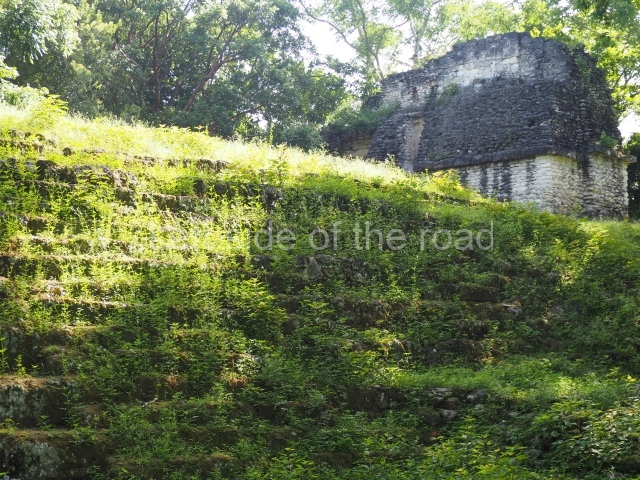

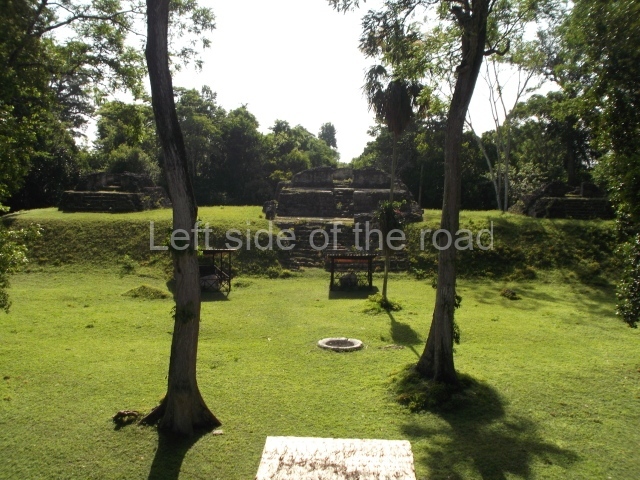

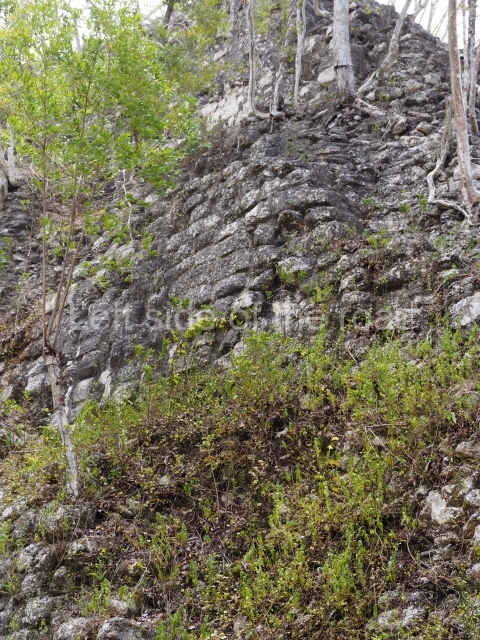

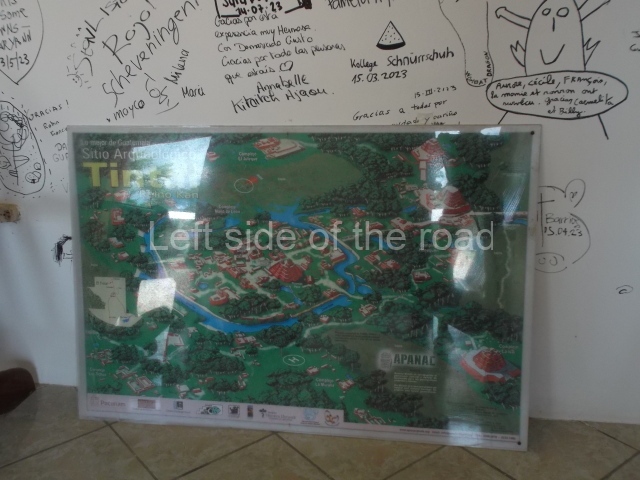

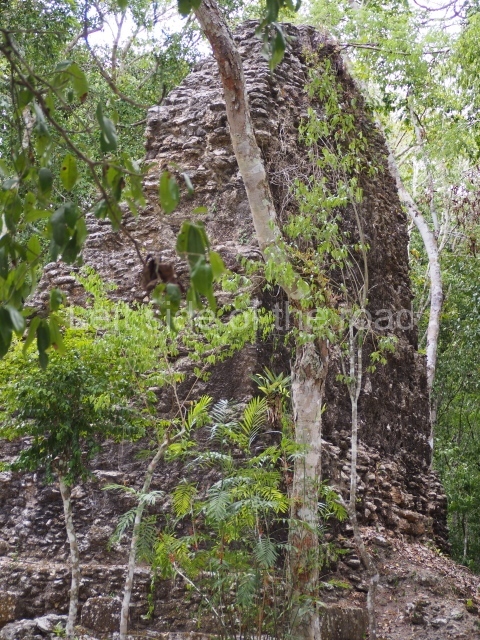

The present-day village, also called Uaxactun, has an old airstrip that cuts through the urban centre and the pre-Hispanic site. It was used for decades during the mid-20th century for the extraction of chicle or gum, which used to be the region’s principal product. Situated to the south are groups D, E, F and a little further away Group H, all of which correspond to the oldest construction periods. North of the airstrip, on the hilltops, lie groups A, B and C, which boast the best architectural ruins, palaces, an acropolis and a wide causeway connecting groups A and B.

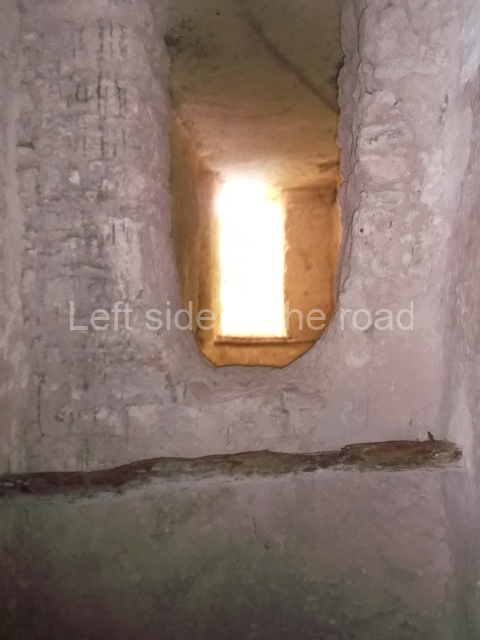

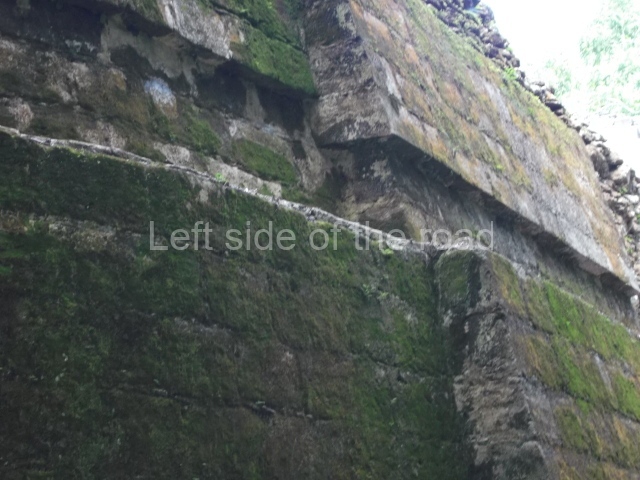

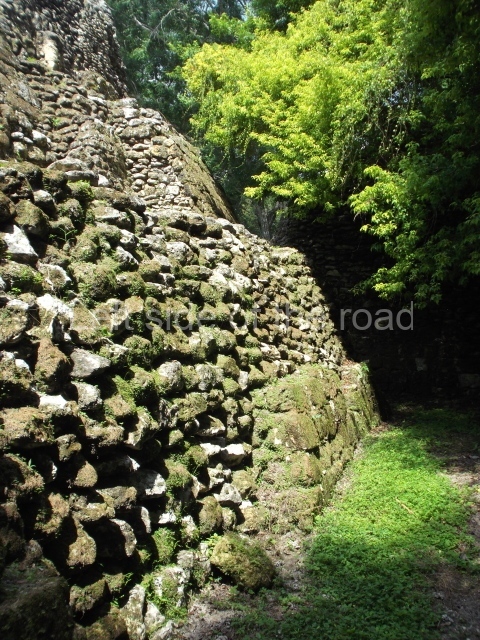

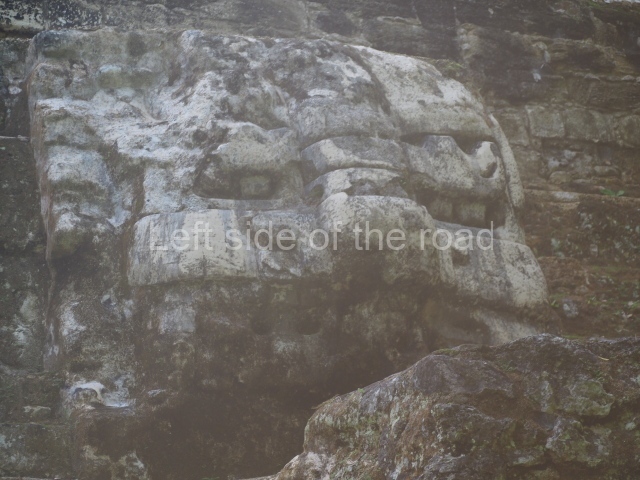

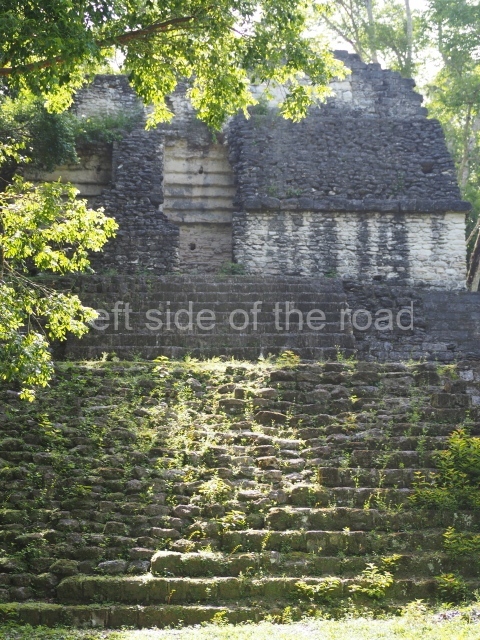

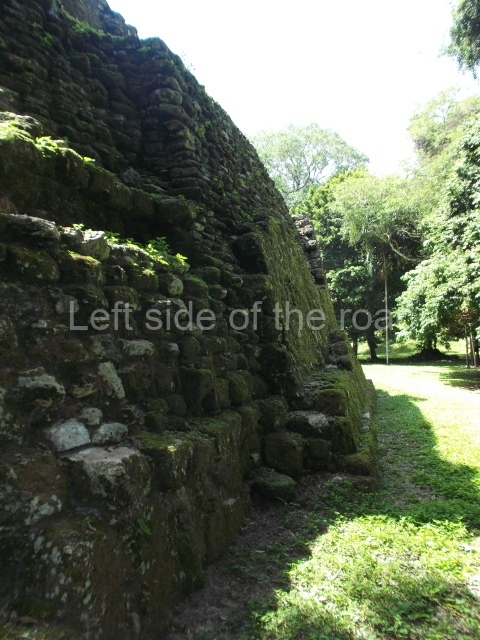

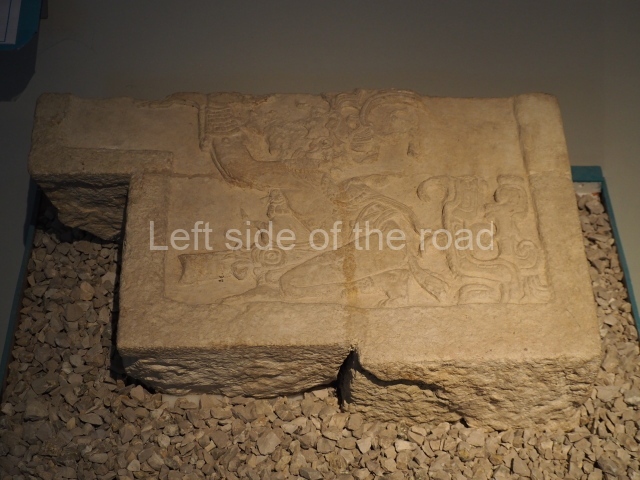

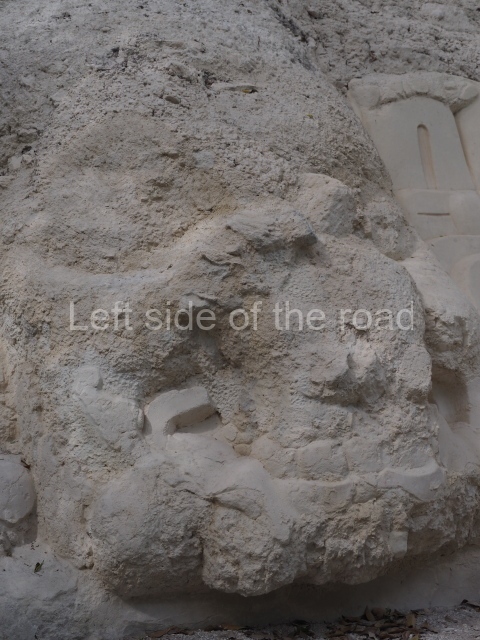

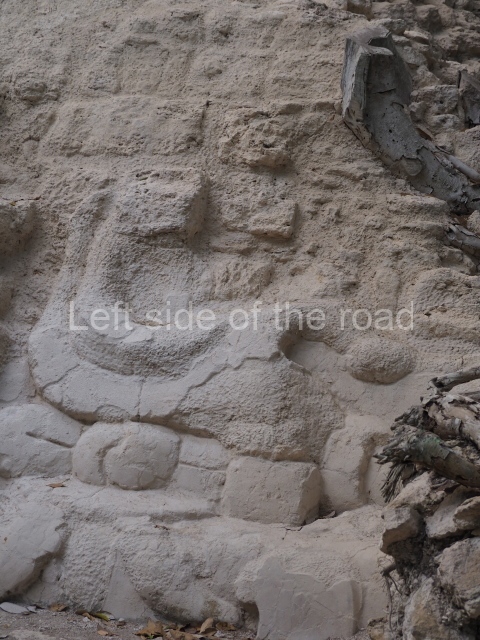

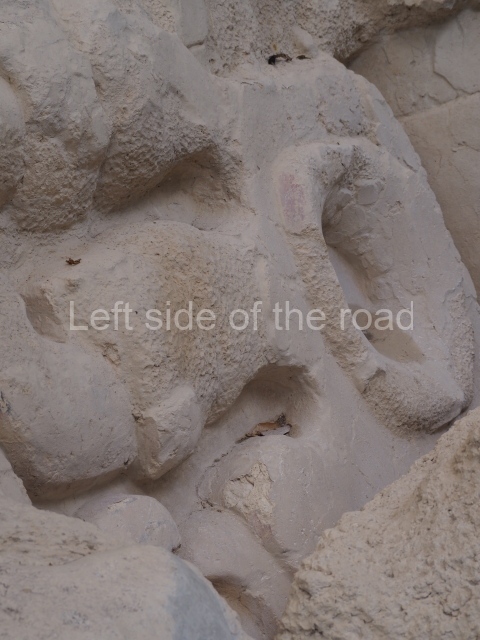

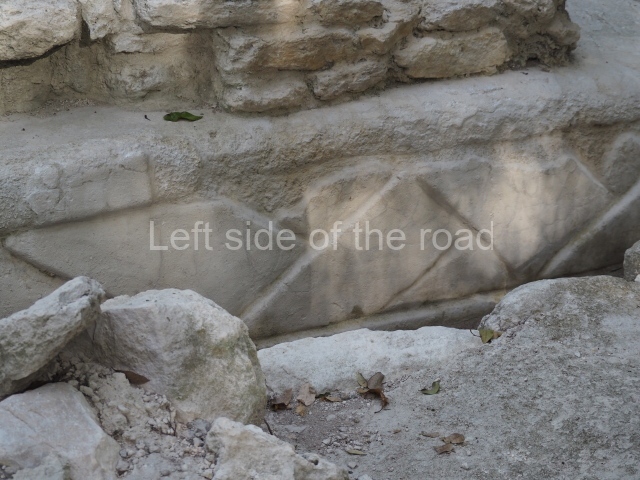

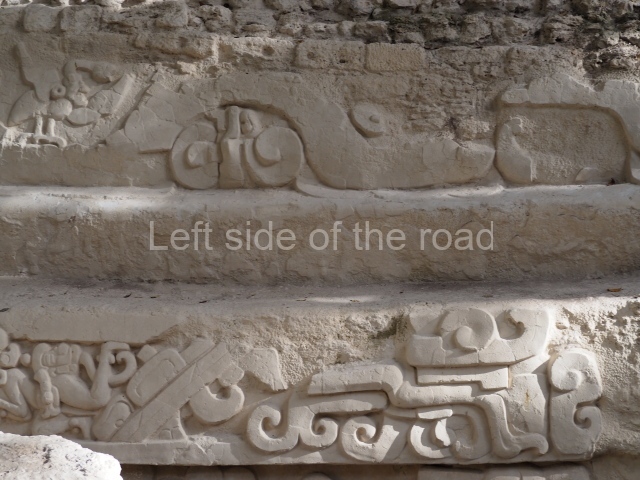

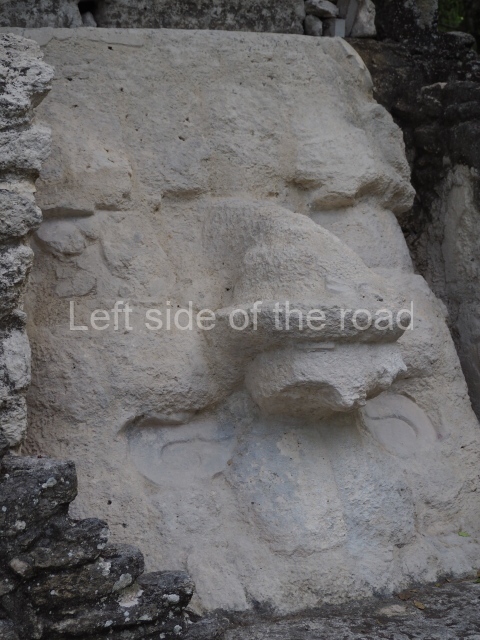

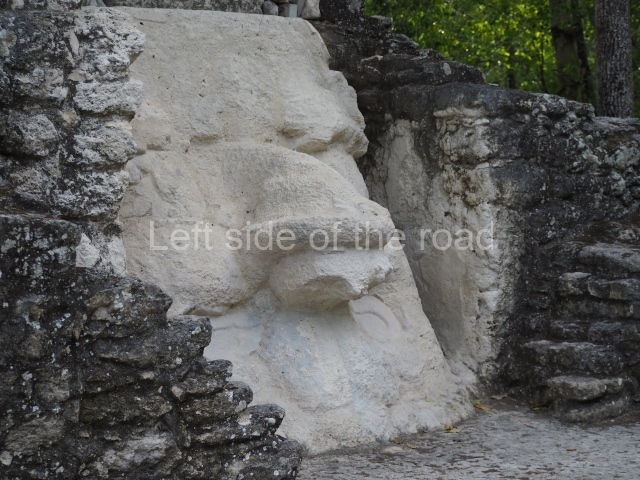

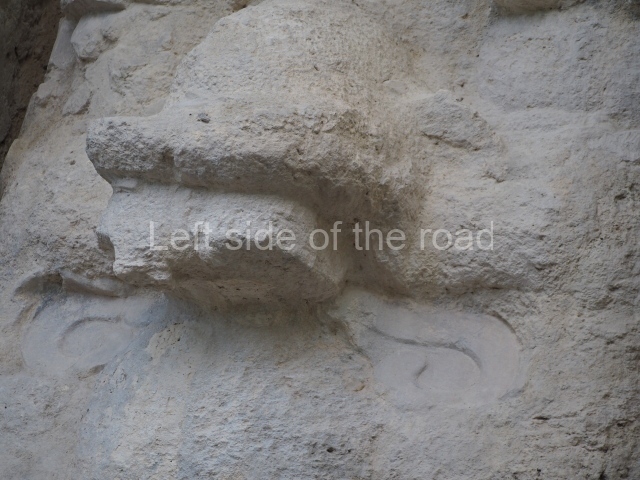

The oldest section of the site is Group E, which dates from around 600 BC. Its earliest inhabitants built wattle-and-daub houses on small limestone platforms, marking the beginning of social differentiation in the core area of the group. Nearby lay the crop fields and several chultunes excavated in the limestone for storing grain after the harvest. The city grew and made significant progress under the guidance of rulers with great vision, who built plazas and large acropolis complexes with buildings that showed off the latest advances in the local architecture. Between 400 and 200 BC, several versions of the astronomical complex were built and a vast plaza to accommodate gatherings of hundreds of people for public ceremonies. Another space with religious functions and strictly reserved for the elite was also built, namely a plaza with three buildings that defined the triadic pattern associated with the three gods of the creation. This place was filled at the beginning of the Early Classic for the construction of buildings E-4, 5 and 6 on top of a huge platform. The prosperity achieved by the local rulers gave rise to the construction of the most beautiful acropolis at Uaxactun during the 1st century BC. The seat of power was transferred to Group H, composed of two plazas, North and South, situated 900 m south of Group E. All the artistic manifestations combined to show human ingenuity: architecture, sculpture, painting and stucco work fused to embellish grand platforms, palaces and pyramidal buildings, which required vast quantities of human labour to transport the clay used for the fillings of the buildings from Juventud, 1 km away. Artists decorated the facades with masks, friezes and human figures painted in red, black, orange, yellow and white. The enormous masks represented the Sun God, the Jaguar of the underworld and the Sacred Mountain. The disposition of the buildings repeats the triadic pattern as a symbolic element, and because of the modest proportions of their spaces they are thought to have been reserved for officials involved in rituals and the administration of the city. Uaxactun boasts the first buildings totally made out of stone, with one or two corbel-vaulted rooms, which again are among the first known examples in the Maya region. For reasons we have yet to discover, Group H was buried and abandoned around the 2nd century AD.

At the beginning of the Early Classic, the nobility decided to move to the hilltops where groups A and B are located. However, the course of the history of Uaxactun changed dramatically when it was subjugated to Tikal in AD 378 at the hands of a nobleman called Siyaj K’ak’, apparently from the Mexican plateau. The short distance between Tikal and Uaxactun, combined with the progress achieved by both cities, had led to increasing rivalry to maintain prestige and territorial control of the region. After this defeat, Uaxactun was overshadowed and successive sovereigns wrote on the sculpted monuments that they were the descendants of Siyaj K’ak’, the dynasty’s ancestor.

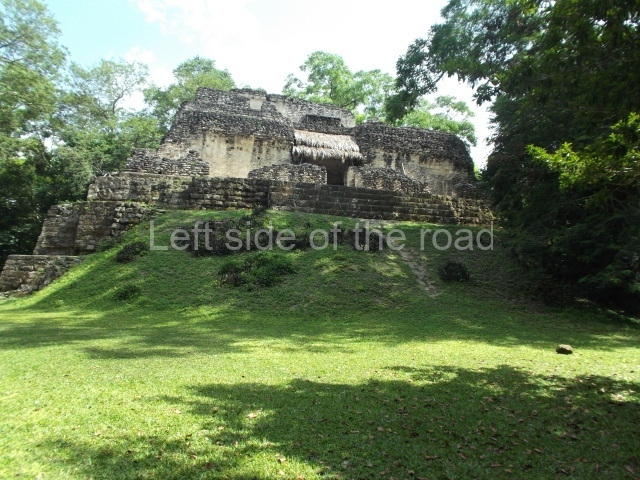

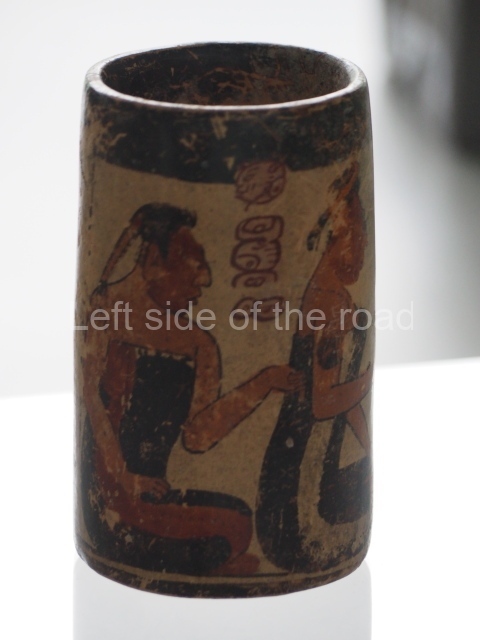

Groups A and B, expanded during the Classic period (AD 250-900), exhibit the best examples of architecture, broad access causeways and the only ball court. Palace B-13 revealed a polychrome mural with two sovereigns, their noble companions and a group of women chatting; unfortunately, it was destroyed by plunderers. Group B is distinguished by several sculpted monuments, but especially by Stela 5, the front of which shows a portrait of Siyaj K’ak’. The Ball Court adopts the north-south orientation of the courts built during the Late Classic and unusually displays a smooth stela that has been reused as part of one of the walls at the north end. From here, a wide and exquisitely made causeway leads to Group A, which is raised, passes in front of Building A-3 and ends at Building A-2 in the Main Plaza, all built during the Late Classic. The Main Plaza also contains several stelae and fragments of smooth and sculpted monuments. Stela 9, discovered by Morley, shows the oldest known sovereign of the site. Opposite Structure A-2 are stelae 12 and 13, the latest sculpted monuments at the site.

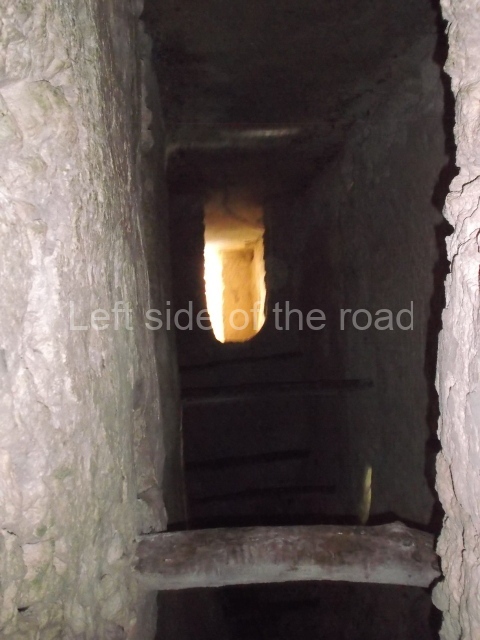

Rising next to the Main Plaza is the Acropolis comprising several buildings known as A-5. This was the seat of power during the Classic period and it is here where five of its famous sovereigns from the Early Classic were buried. The East Plaza is distinguished by Palace A-18, the most handsome construction on the whole site, built on a platform and comprising two storeys and 18 rooms. An internal staircase leads to the top storey, where it is still possible to see the remains of a stone throne on which the sovereign would sit to observe his subjects gathered in the plaza. Four causeways that connected the main urban groups on the site have been discovered, as well as three aguadas, a pre-Hispanic well with fresh, crystalline water and various quarries that provided blocks of stone for construction purposes. The last Uaxactun rulers were Olom Chik’in Chakte and K’al Chik’in Chakte, who reigned in the AD 830 and 889, respectively. The references to the latter ruler appear on Stela 12, which also mentions the visit of Hasaw Chan K’awil II, the last king of Tikal, who came to participate in a ritual. Stela 12 was the last monument sculpted at the city, a few decades before Uaxactun was abandoned forever.

Juan Antonio Valdes

From: ‘The Maya: an architectural and landscape guide’, produced jointly by the Junta de Andulacia and the Universidad Autonoma de Mexico, 2010, pp220-223.

1. group A; 2. Group B; 3. Group C; 4. Group D; 5. Group E; 6. Group F.

Getting there;

From Santa Elena. Each day there’s a bus that is scheduled to leave Santa Elena bus station at 13.00 – but it will often leave later and take a long time to get out of the city and on the main road. Be patient. It will arrive in Uaxactun at around 17.00. Foreigners will have to get out at the National Park entrance (about 18km before the archaeological site of Tikal) and pay the park entrance fee. This is currently Q150 per day. You will need at least 2 nights in Uaxactun to visit the ruins there. That means 3 days in the park and consequently Q450. You can combine a visit to Tikal on the way back to Santa Elena at no extra cost. (See Tikal post for details of how to negotiate your visit there if you have luggage.) Santa Elena-Uaxactun Q60, Uaxactun-Tikal Q15, Tikal-Santa Elena Q50;

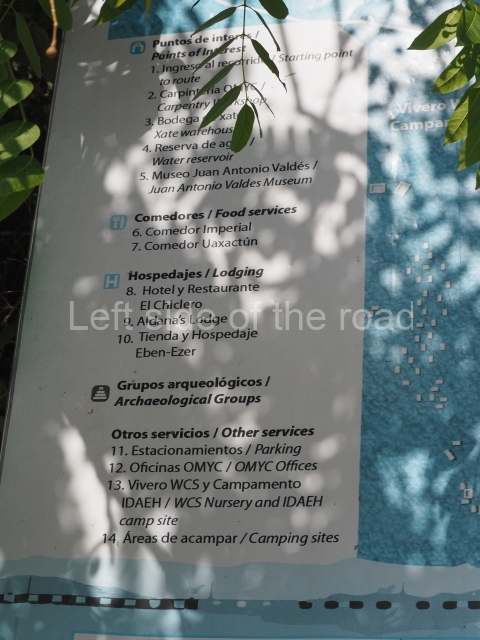

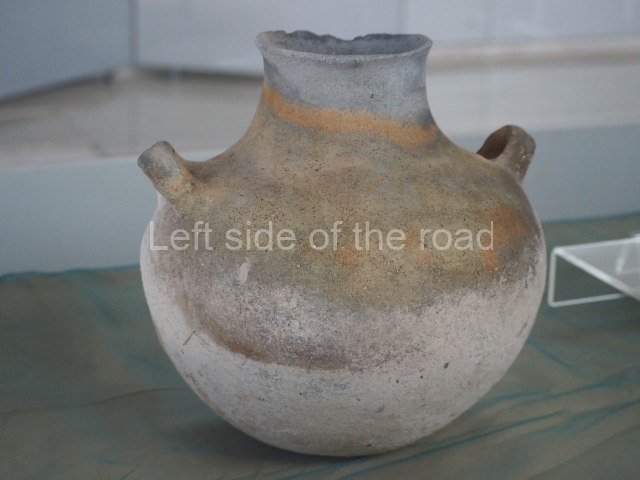

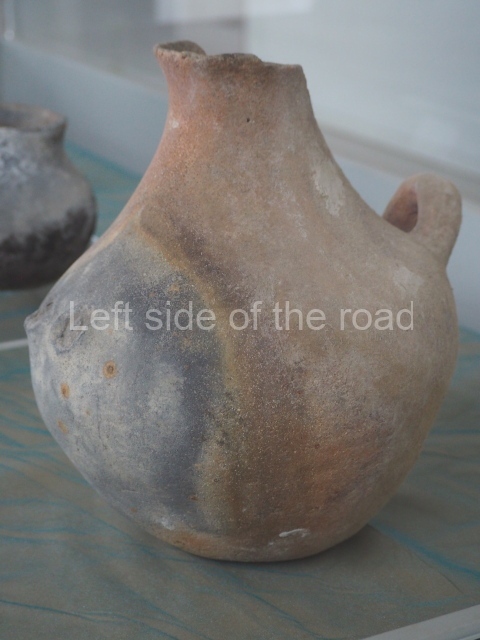

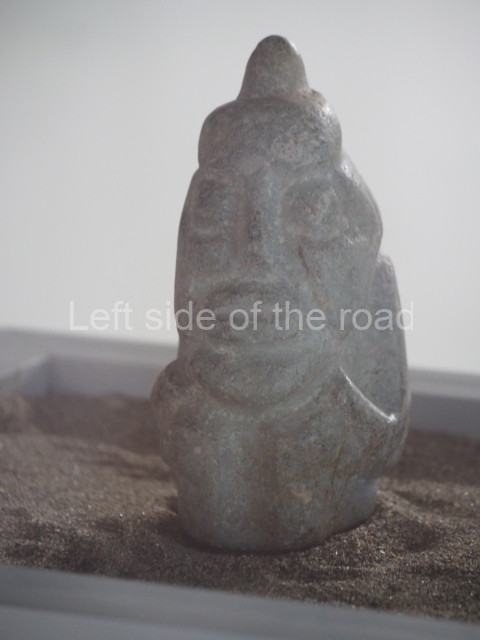

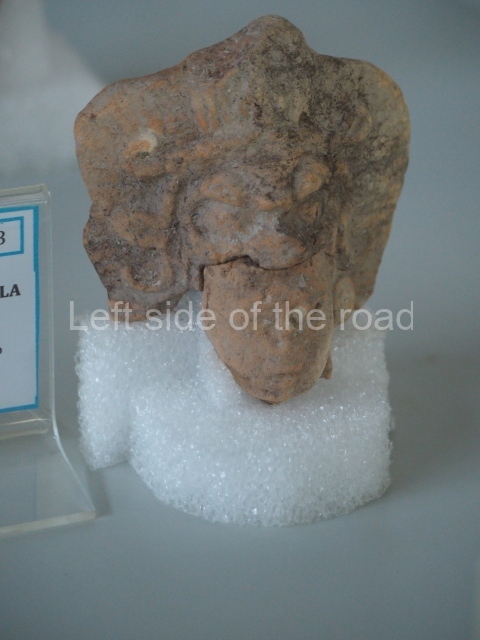

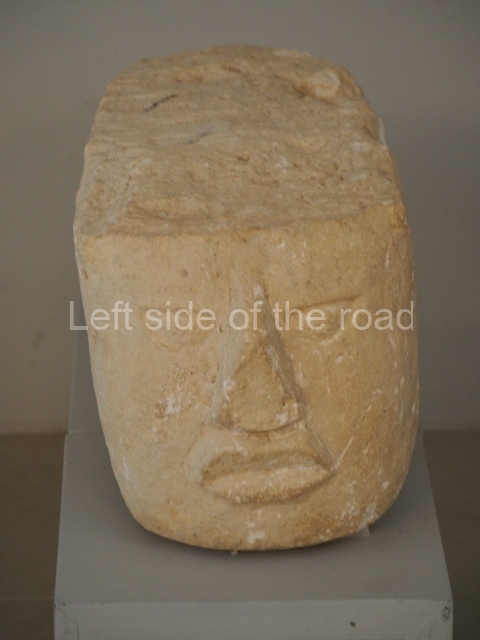

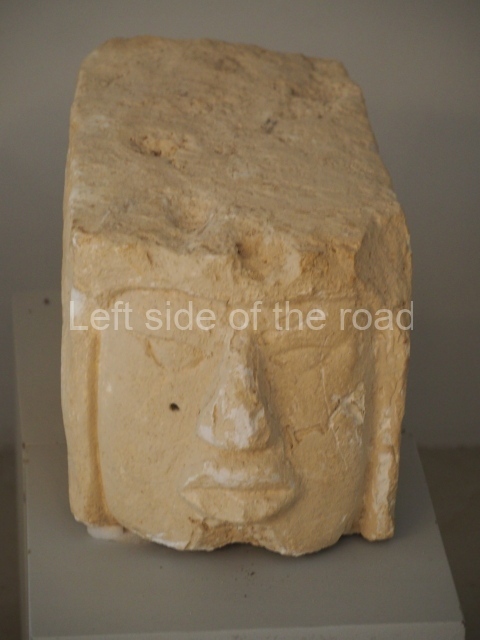

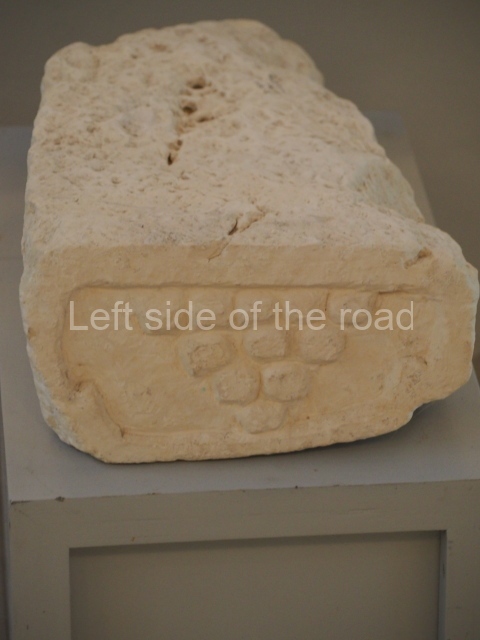

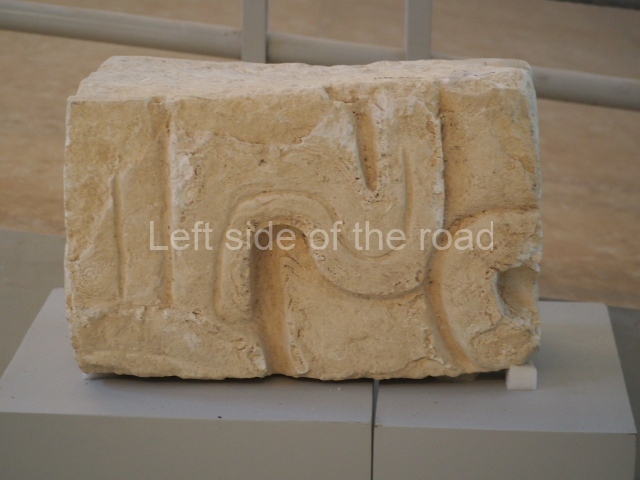

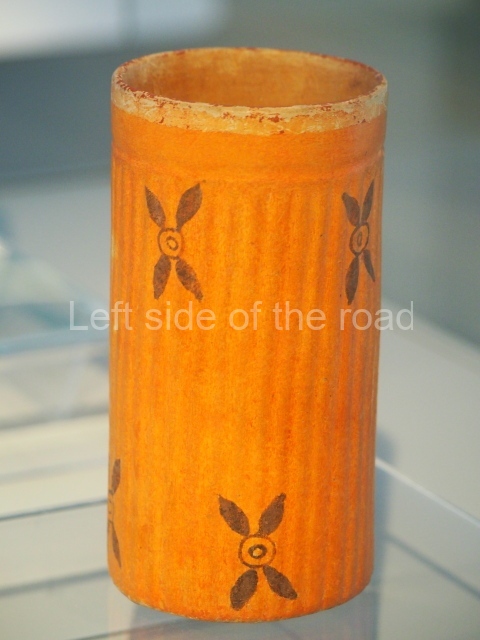

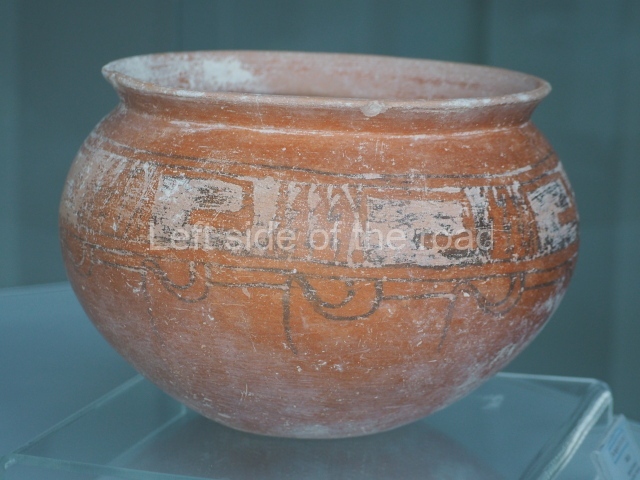

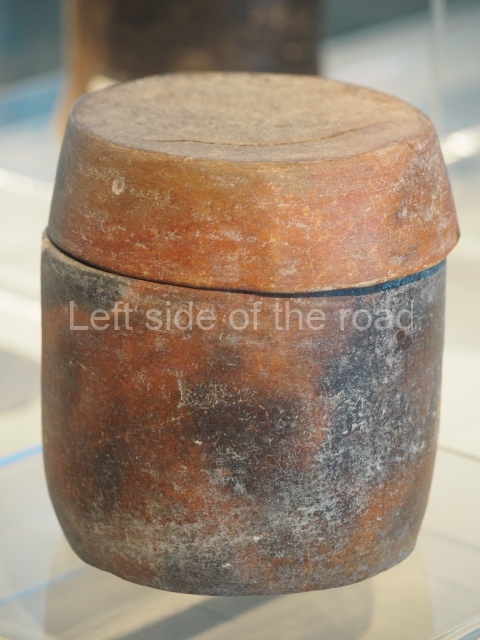

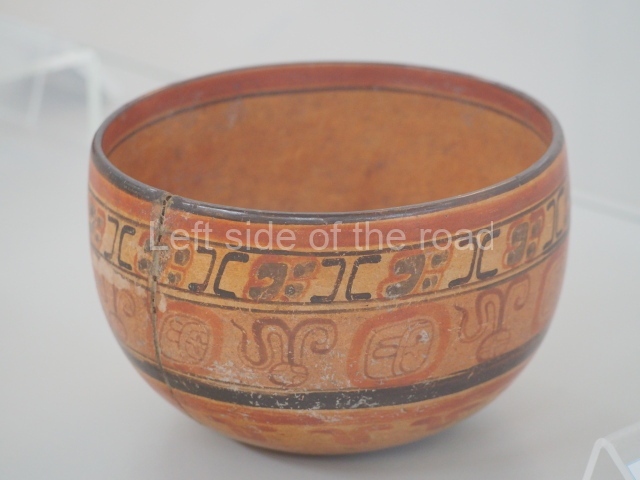

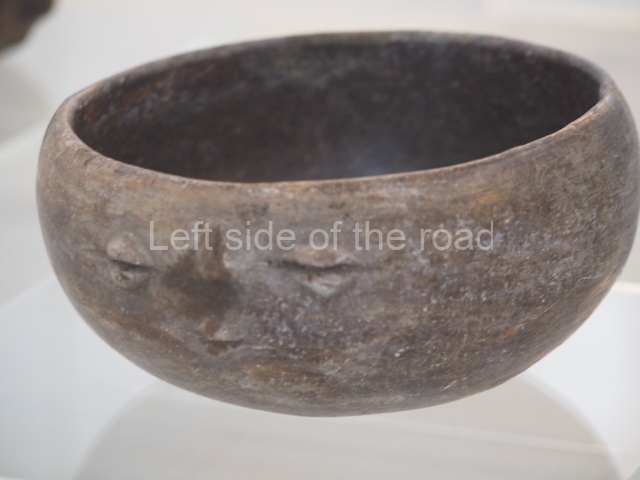

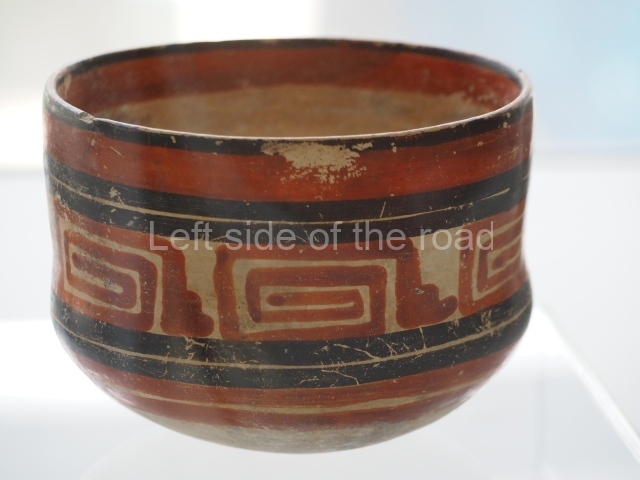

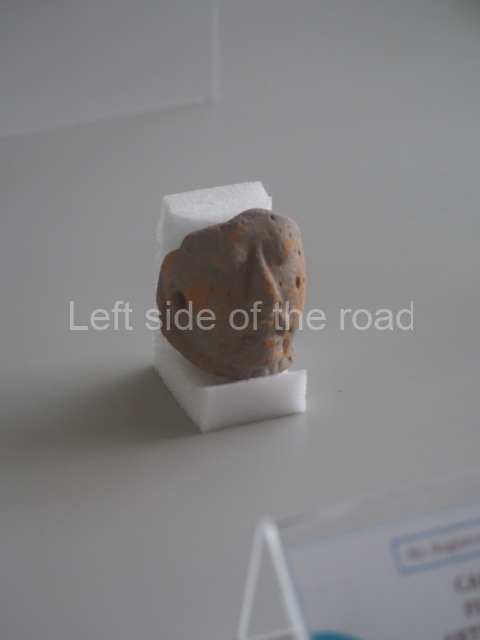

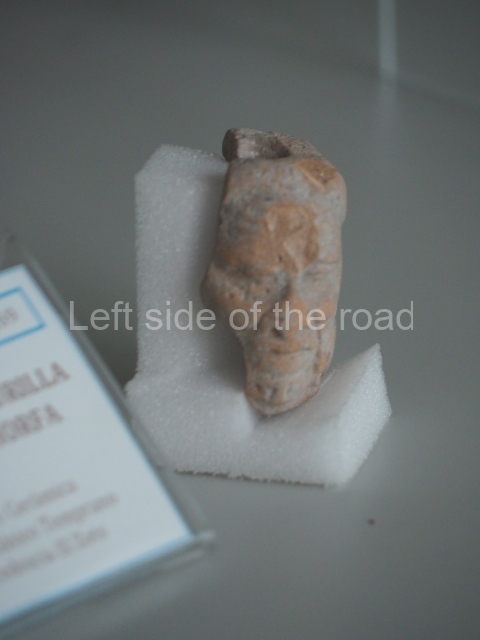

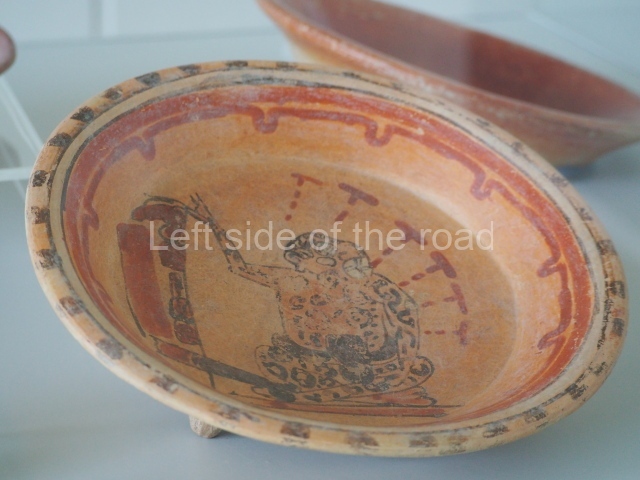

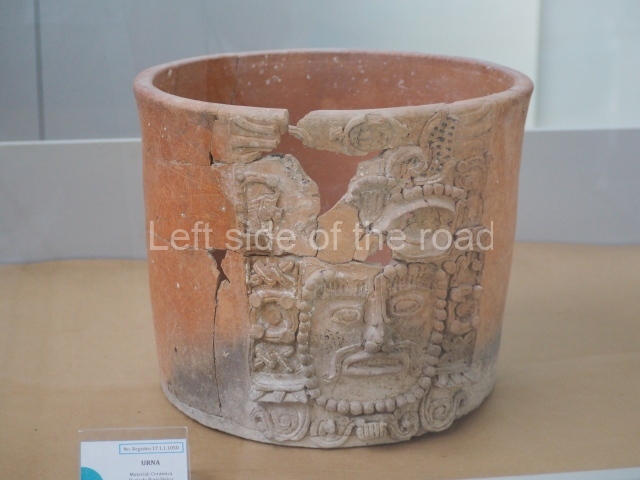

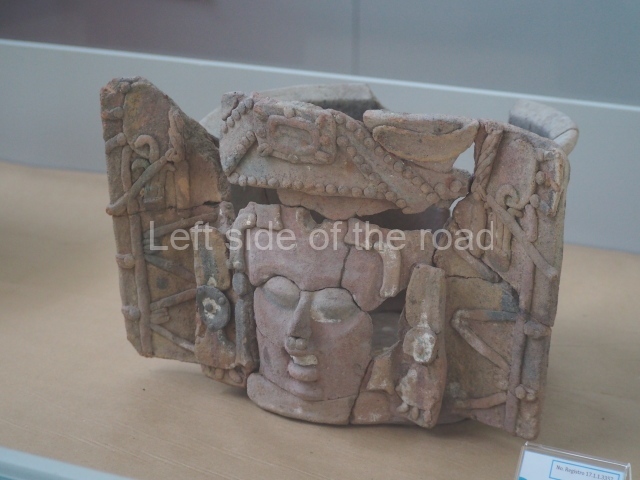

There are three places to stay in Uaxactun, Hostel El Chiclero (which looks down on what used to be the airstrip, on the left side as you enter the village), Aldana’s Lodge which is in a street behind El Chiclero and Eben-Ezer Hospedaje (which I think is run by the bus owner). El Chiclero also houses a small museum with finds from the site. (In the summer of 2023 most of the 570 items in the collection were in boxes. There’s no money to display them properly but it’s still worth asking to see the museum if you are there. I saw some items I hadn’t come across before.)

The archaeological sites are on either side of the airstrip, clearly marked from the village ‘centre’ but you have to keep your eyes open for the subsequent turn-offs.

The bus from Uaxactun for Tikal/Santa Elena starts to pick up people at 06.45. The journey to Tikal takes about 45 minutes. Q15.

GPS:

17d 23′ 28″ N

89d 37′ 47″ W