Teatralnaya – Line 2 – A Savin

More on the USSR

Moscow Metro – a Socialist Realist Art Gallery

Moscow Metro – Teatralnaya – Line 2

Teatralnaya – Line 2 – 01

Teatralnaya (Russian: Театра́льная, English: Theater) is an underground metro station on the Zamoskvoretskaya line of the Moscow Metro, named for the nearby Teatralnaya Square, the location of numerous theatres, including the famed Bolshoi Theatre. The station is unique in that it does not have its own entrance halls. The north escalator leads to Okhotniy Ryad and the south escalator to Ploshchad Revolyutsii.

Teatralnaya – Line 2 – 04

History

Ploshchad Sverdlova station opened on September 11, 1938, as part of the second stage of construction of the Moscow Metro system. It was the terminal station of the Zamoskvoretskaya line until the line was extended on January 1, 1943. Teatralnaya’s architect was Ivan Fomin. The station is located at a depth of 33.9 meters (111 feet). The central hall has a diameter of 9.5 meters (31 feet), with an 8.5 meters (28 feet) lateral lining of cast-iron tubing.

From its opening until 1990, the station’s name was Ploshchad Sverdlova, which was named in honour of the prominent Bolshevik, Yakov Sverdlov. In 1990, the city changed the name of the square to Teatralnaya Ploshchad. The name of the station followed accordingly.

Teatralnaya – Line 2 – 03

Decoration

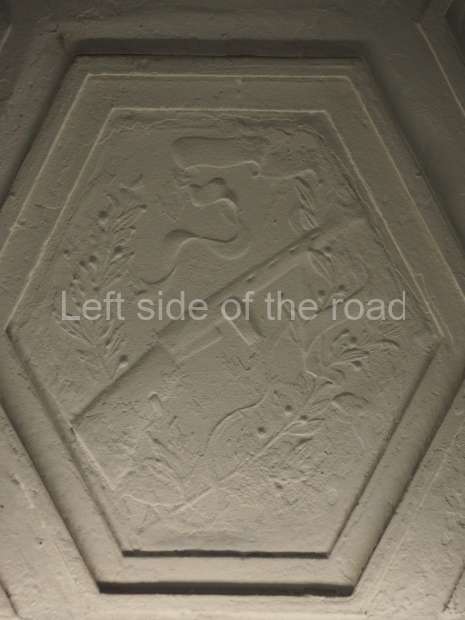

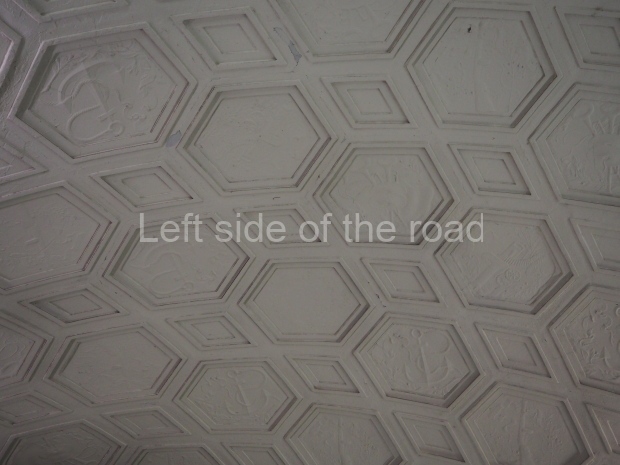

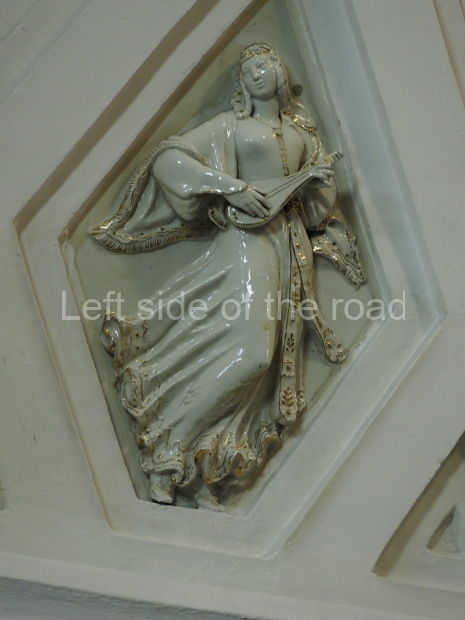

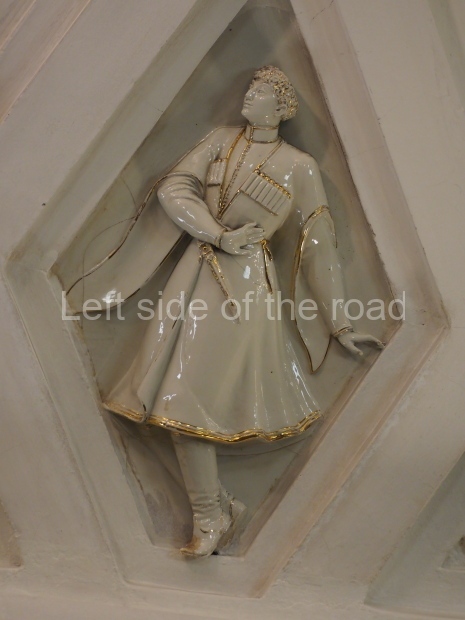

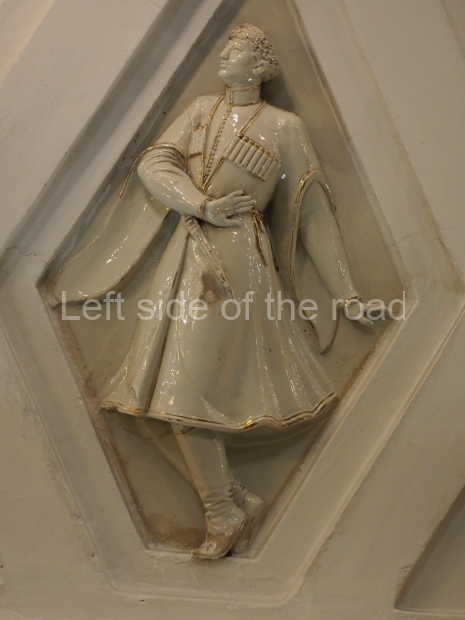

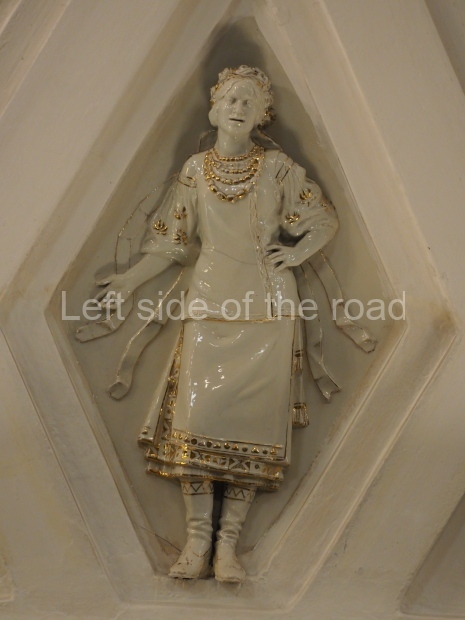

Teatralnaya Station has fluted pylons faced with labradorite and white marble taken from the demolished Cathedral of Christ the Saviour. Crystal lamps in bronze frames attached to the centre of the room give the central hall a festive appearance. The vault of the central hall is decorated with caissons and majolica bas-reliefs by Natyla Danko on the theme of theatre arts of the USSR, manufactured by Leningrad Porcelain Factory. These bas-reliefs are a series of fourteen different figures, each representing music and dance from various nationalities of the Soviet Union. Seven male and seven female figures attired in their national costumes are either performing an ethnic dance or are playing a distinctively ethnic musical instrument. The series included Armenia, Byelorussia, Georgia, Kazakhstan, Russia, Ukraine and Uzbekistan. Each figure is reproduced four times for a total of 56 figures. Initially, the floor was of black-and-yellow granite patterned as a chessboard; however in 1970, the yellow panels were replaced with gray.

OLYMPUS DIGITAL CAMERA

A bust of Yakov Sverdlov, for whom the station was originally named, was located at the end of the platform opposite the escalators. Only the base remains today. A bust of Vladimir Lenin was however, preserved.

Text above from Wikipedia.

Teatralnaya

Date of opening;

11th September 1938, known as Ploshchad Sverdlova till the 5th November 1990

Construction of the station;

deep, pier, three-span

Architect of the underground part;

I. Fomin

Transition to stations Okhotny Ryad and Ploshchad Revolyutsii

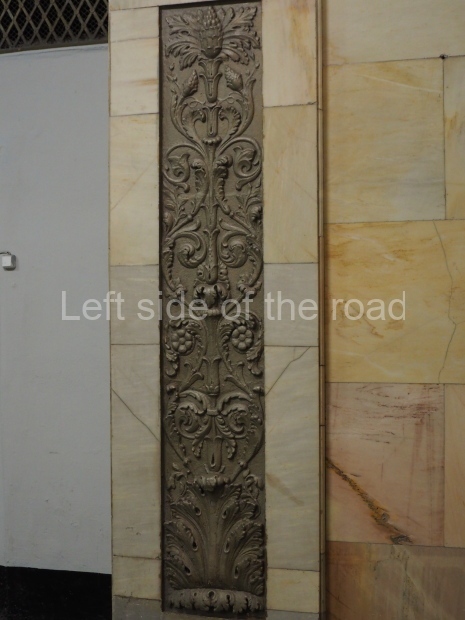

The cubic pylons of Teatralnaya are faced with slightly yellowish grainy marble. The pylon edges are decorated with round broken-rib columns. Lamp-brackets with two white spherical shades are between the columns. Benches are placed at the bases of the pylons.

The vault of the very short central hall is decorated with rhomb-like coffers, while the vaults of the track tunnels are with square coffers. There are round porcelain medallions alone the base of the main vault – ‘Folk Music and Dance’ manufactured at the Leningrad Porcelain Factory by painter

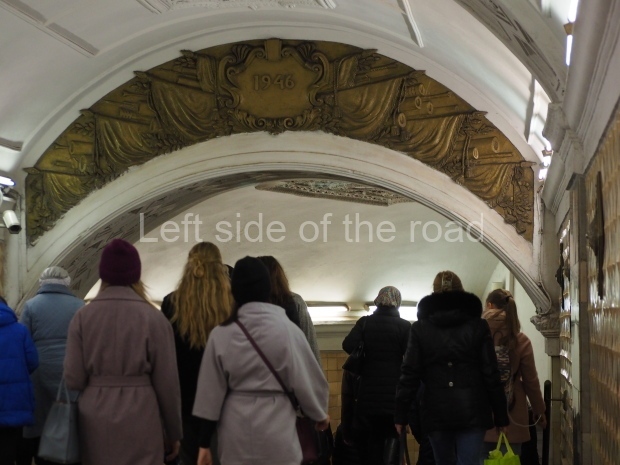

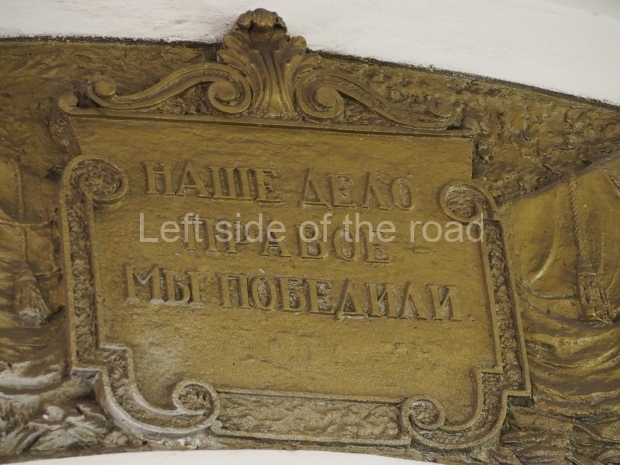

Danko’s cartoons. The transit to station Okhotny Ryad begins with a bridge in the central part of hall, which ends by a small hall from which a long running-up passageway starts (built in 1945-1946). The left and right walls of the small hall have medallions with Chaikovsky’s profiles. The pediments of the bridge are adorned with bas-reliefs of pair ballet jump and ballet support. The northern exit ends in the underground entrance hall common with station Okhotny Ryad. There is a portrait of K. Marx on the wall made of red and white marble as Florentine mosaic.

Text from Moscow Metro 1935-2005, p68/9

Location:

Tverskoy District, Central Administrative Okrug

GPS:

55.7578°N

37.6190°E

Depth:

33.9 metres (111ft)

Opened:

11 September 1938

More on the USSR

Moscow Metro – a Socialist Realist Art Gallery