Butrint, Saranda

More on Albania ……

Butrint – a Greek and Roman story in southern Albania

An archaeological site that goes back almost 2500 years, Butrint has the imprint of both the Greek and Roman civilisations. Important for its location to both those cultures it was also pivotal under Venetian rule, its decline only really beginning after it fell to Napoleon’s armies at the end of the 18th century.

One of the main visitor attractions in the vicinity of Saranda is the archaeological site of Butrint, about 14km to the south (after passing by the Dema Monument and through the town of Ksamil), easily reached by a regular public bus from the town centre.

One reason that makes it special is the fact that it was occupied by some of Europe’s principal civilizations starting with the Greeks, who first developed the site in the 4th century BC, followed by the Romans from the 2nd to the 6th centuries AD, and then reaching a final period of importance and influence under the Venetians from 16th century until succumbing to the French armies of Napoleon at the end of the 18th century. It was subsequently occupied by a local despot but by that time it had lost its historic importance.

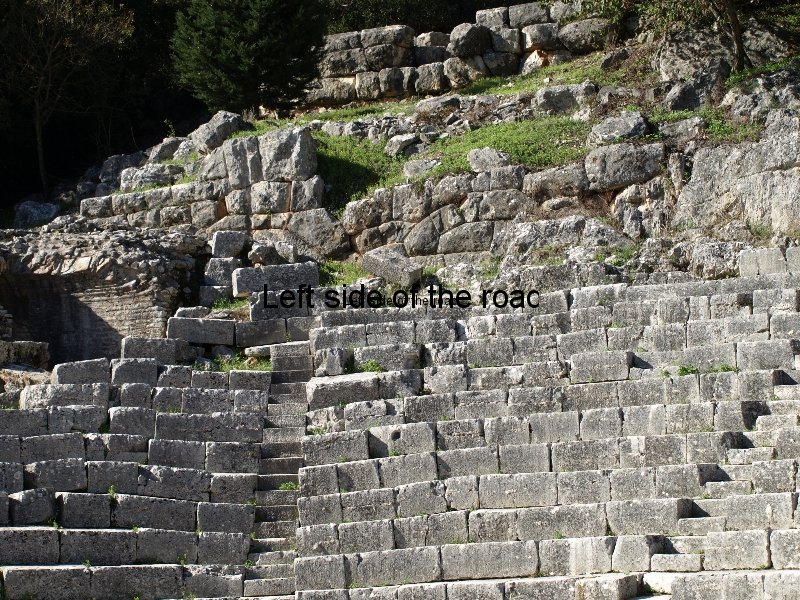

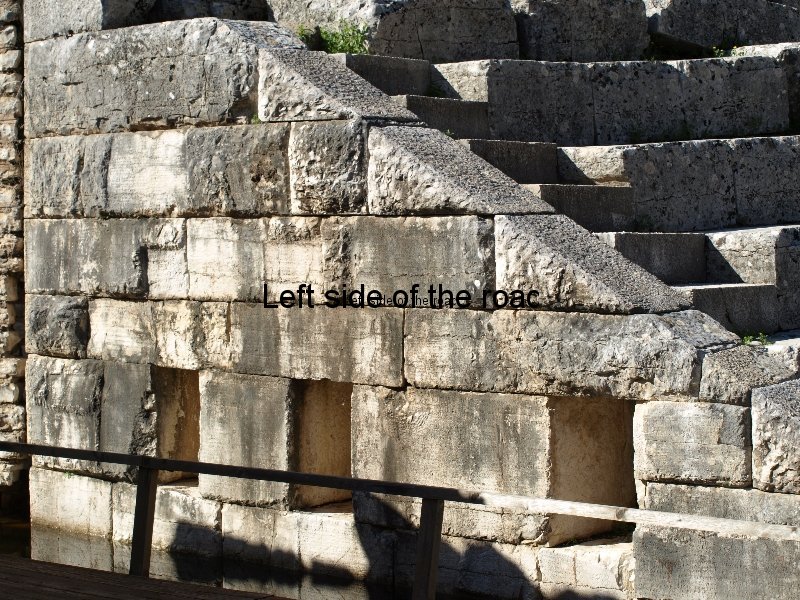

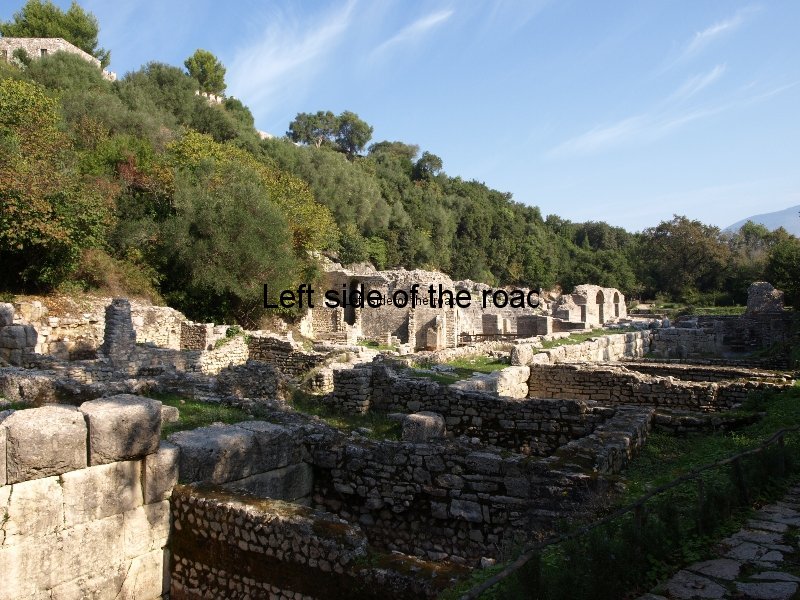

Especially interesting to me was the way the Roman’s just took over the Greek city and adapted, and extended, it to their own particular philosophy and way of doing things. For example, they expanded the theatre, built bath houses and other public buildings and altered the whole atmosphere of the place by constructing a huge Forum, Roman life revolving around that part of any city. culture.

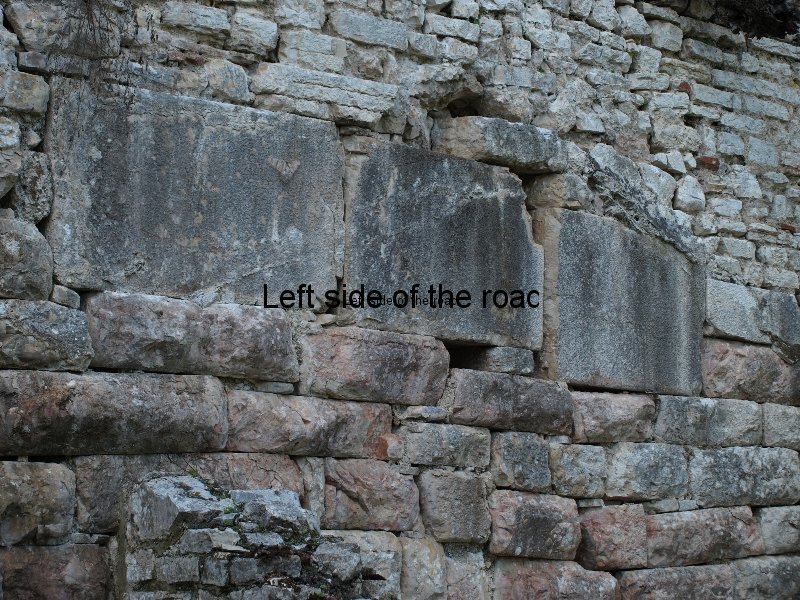

This foundation was then later, literally, built upon by succeeding civilizations, with a development of the fortifications and a strengthening of the perimeter walls as the technology of warfare became more lethal and adept at breaking down a population’s resistance. Yes, the Romans built walls but their primary defence was the threat of total, complete and absolute destruction if anyone dared to attack a Roman settlement, something that was valid until the collapse of the Empire in the 5th century AD.

It’s not a huge site and a couple of hours is adequate to get a good idea of the place, at a reasonable pace. Each time I go there the level of the water seems to get higher and from what I’ve read this was a problem from many centuries ago, forcing the abandonment of some of the lower structures.

At the moment the orchestra of the Greek/Roman theatre seems to be constantly under water, to such an extent that terrapins are regular visitors. What this flooding is doing to the structure of the buildings I don’t know, but it can’t be good news.

So what do I recommend?

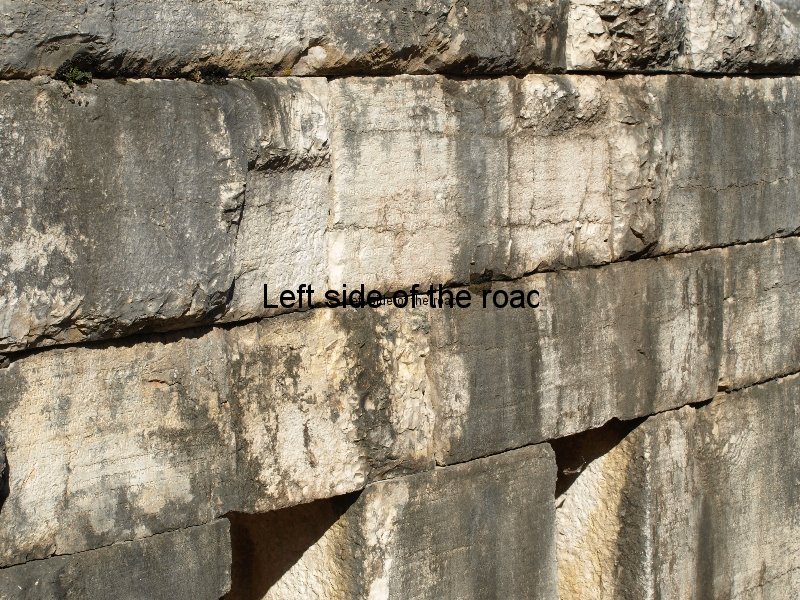

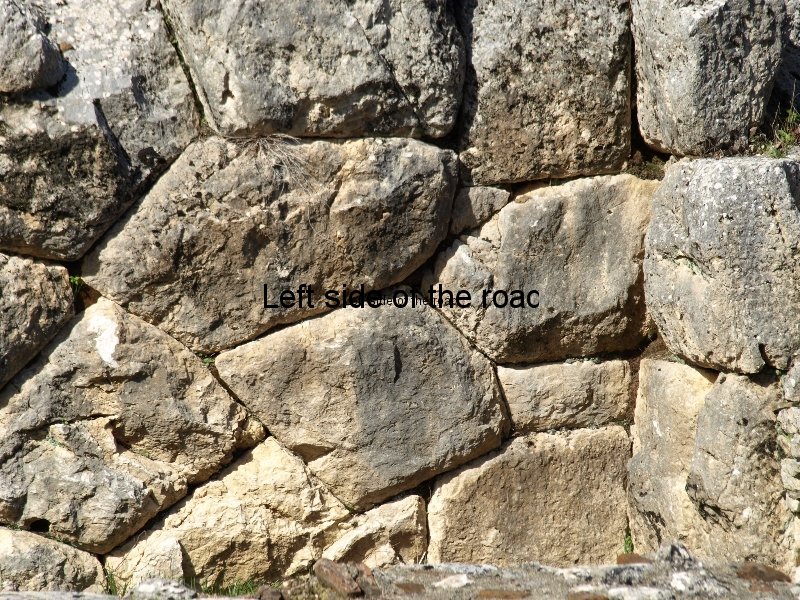

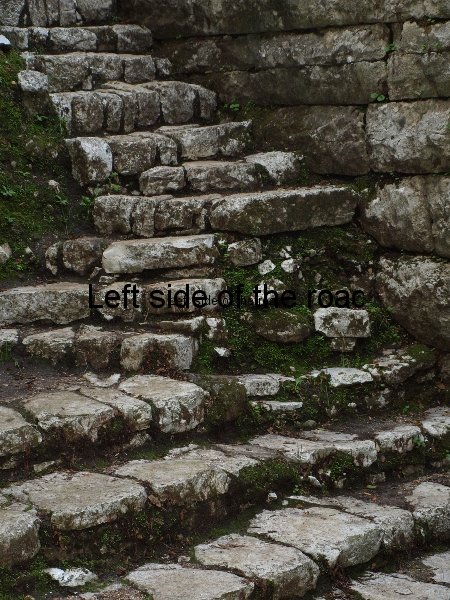

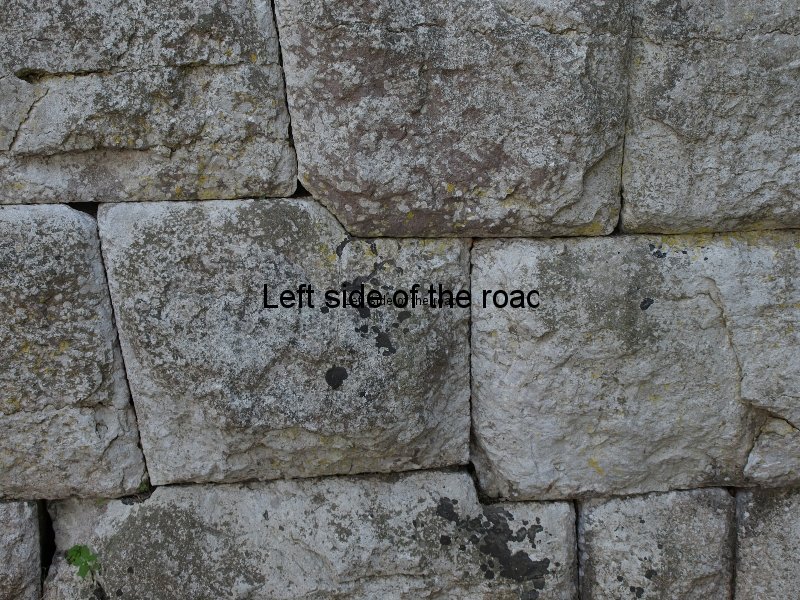

The changing manner in which the Greeks and the Romans put one stone on the top of another. There is a very distinct change in the way they constructed their buildings, although they had basically the same use. What I found interesting was the similarity in building style of the Greeks to that of the Incas in Peru. At Butrint, as in Cuzco and Machu Picchu, large, worked pieces of stone are fitted together as in a jigsaw puzzle, so that there are no straight lines, I assume for a similar reason, i.e. there are no lines which provide a weak point in the event of an earthquake.

Archaeologists working in Butrint during Socialism

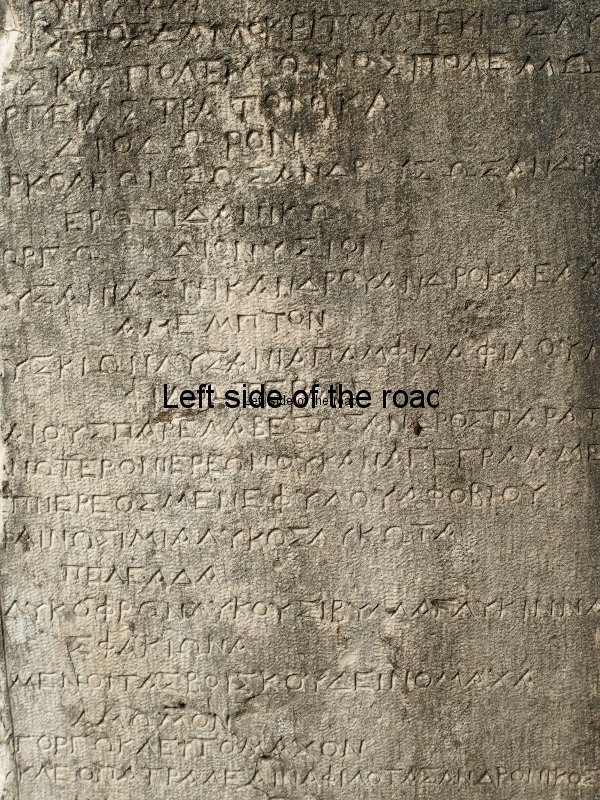

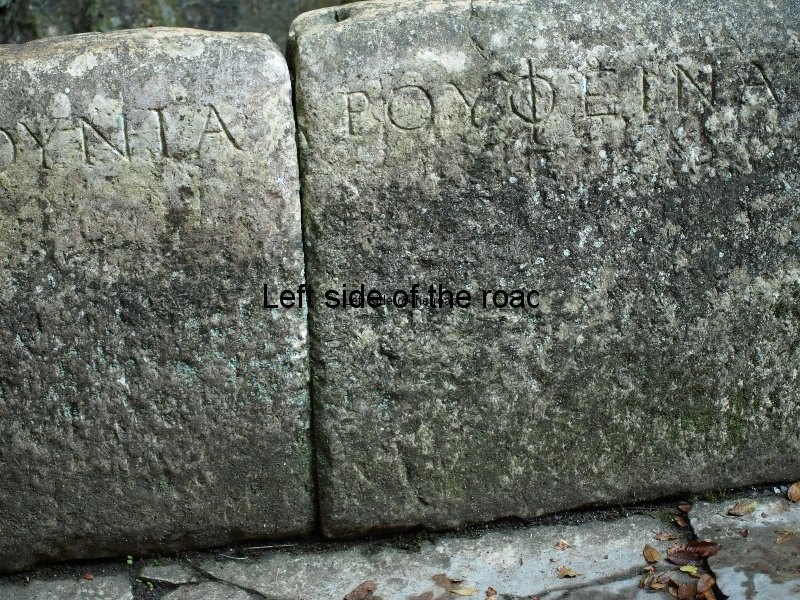

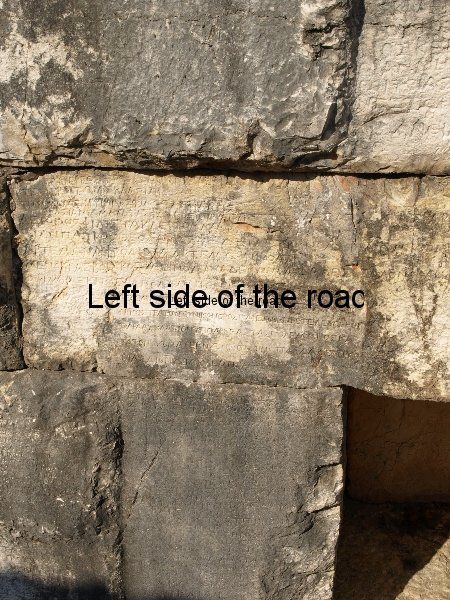

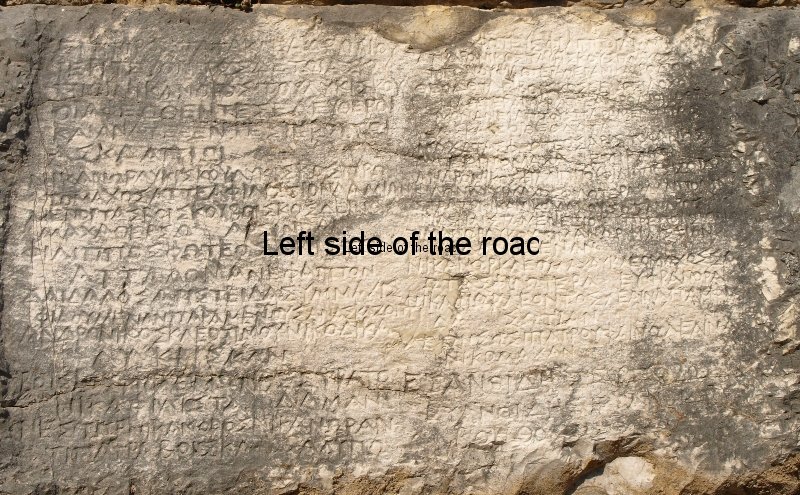

When you follow the path and wooden walkway taking you to the theatre look to your left just as you are about to reach the stage and the bottom of the seating. This is partly under water but there is enough at body level to see the writing in Greek, carved into the stone. Some of these are declarations of manumission made by rich Greeks who gave ‘freedom’ to their slaves in honour of one of the many gods worshipped at the time. Very easy to miss if you don’t look for them but easy to spot if you know where to look. They are referred to in the small museum in the castle complex at the very top of the site.

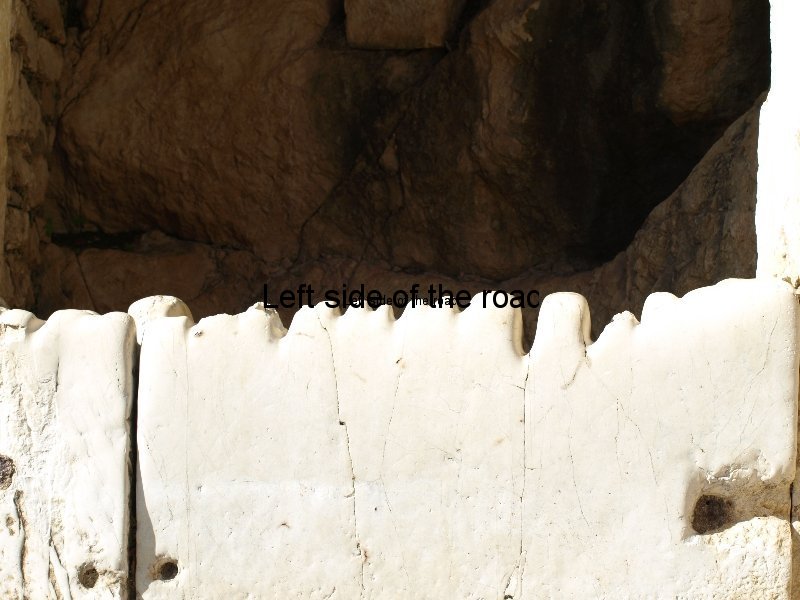

One place that doesn’t get a great number of visitors, due to the fact that the forum area is in front of it and people don’t make the slight diversion off the main path, and that’s the well. It’s only a small well, but what makes it special is the way that the stone has been grooved by the hundreds of thousands of time, over the centuries, a rope has rubbed against the edge with a heavy bucket of water on the end of it. It looks like a row of badly worn teeth.

The Baptistery would be the place to see if preservation of the mosaic wasn’t the most important consideration. When excavations were made an intricate and very well-preserved mosaic was discovered. But like all mosaics the biggest threat comes from the elements (nobody really steals floor mosaics – they become a somewhat difficult jigsaw to reconstruct) and is permanently covered to protect it. This is a small circular structure to the left of the signed route, not too far from the lakeside.

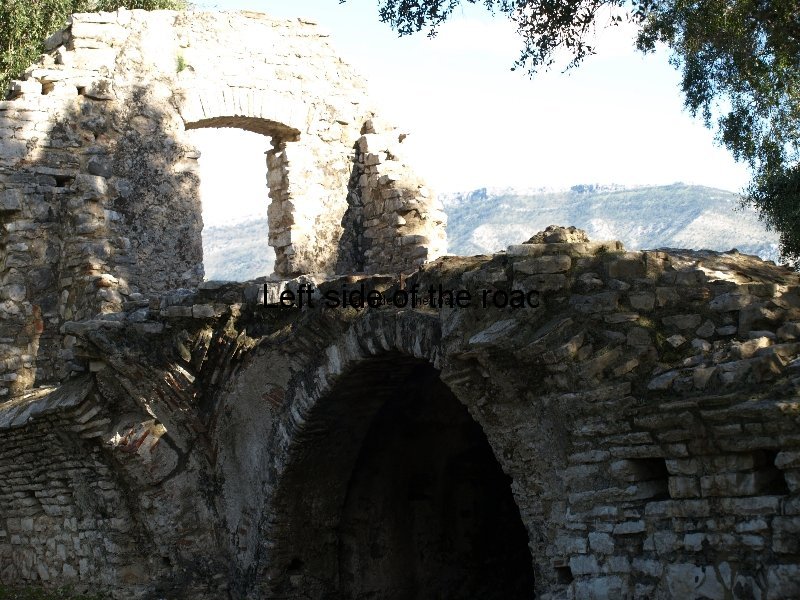

The Basilica is interesting in the fact that it wasn’t a Roman building taken over by the Christians but one constructed at the end of the 6th century, close to the end of the Roman Empire. This is in the classic cross design which is the basis for most Christian churches and is in a surprisingly good condition. OK there are no walls and the roof has also gone the way of all things, but the main columns still exist and it doesn’t take too much imagination to think what it would have looked like in its heyday.

Continuing along the path it’s worthwhile taking a look at the different stages in the development of the city’s defensive walls. This illustrates the different ways of putting stones on top of one another and demonstrates the importance of the place in times past.

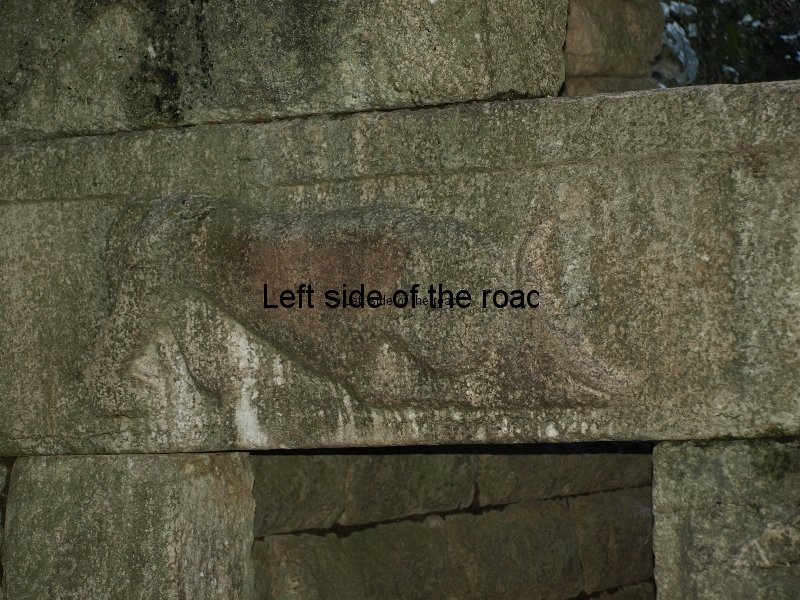

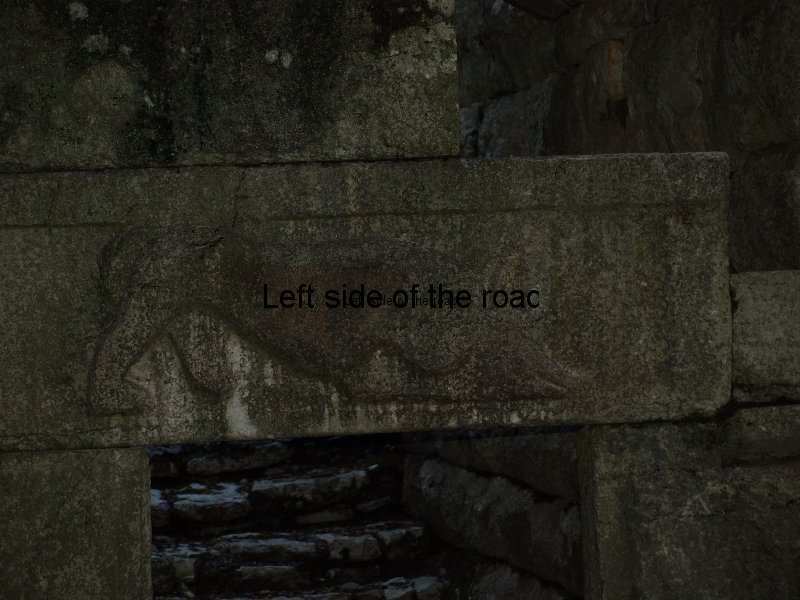

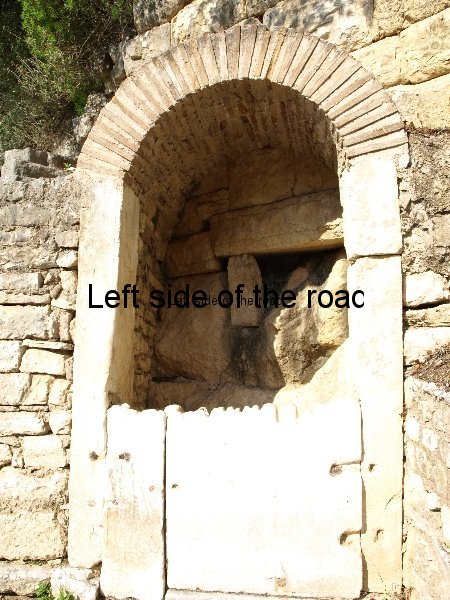

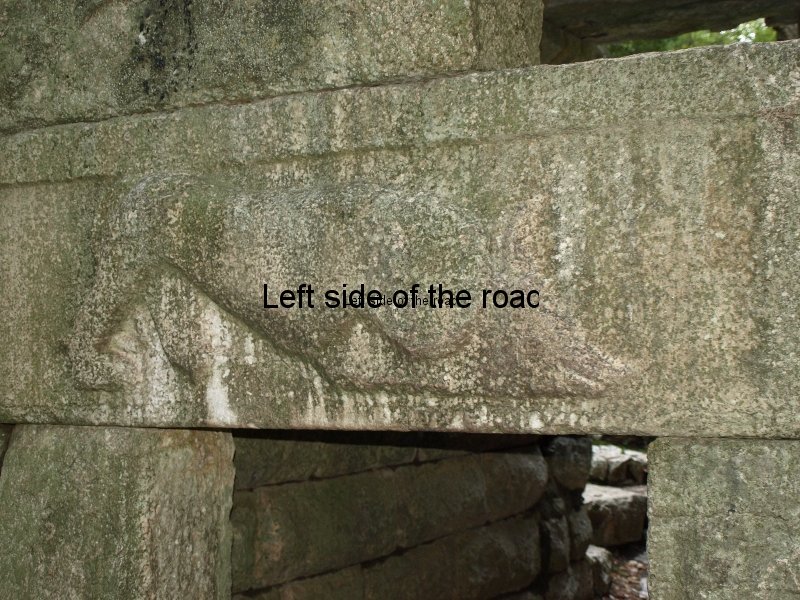

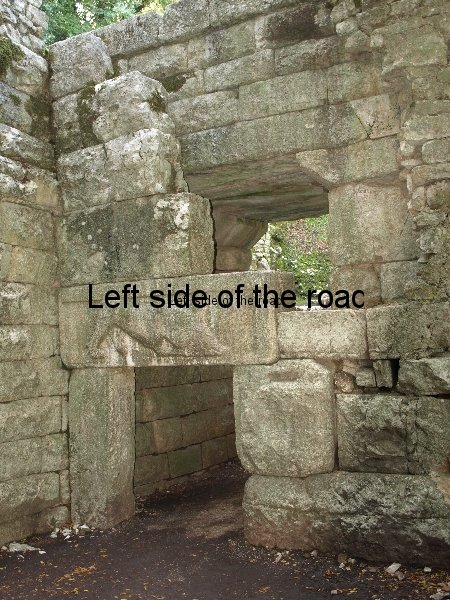

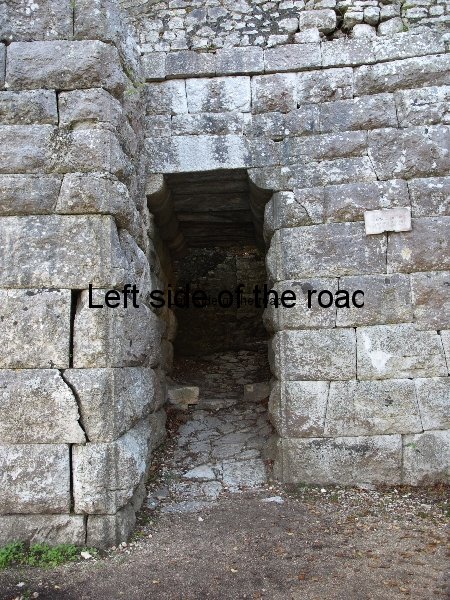

There are a couple of entrances worthy of investigation. The first is what is known as the Lake Gate, dating from the beginning of the settlement. Here take a look at the way the stones in the roof have been worked so they are curved. A little further along the Lion Gate (so-called because there is a carving of a lion devouring a bull’s head on the lintel) shows how the entrance was lowered so that anyone coming through would have to bow their heads. Inside this entrance there is a well and although it’s impossible to make it out now there were some colourful Christian wall paintings towards the top. The dampness of the area (now permanently in the shade) has destroyed whatever might have been there many years ago.

Many discoveries were made during the period of Socialism as research into the country’s past was considered important to get a greater understanding of its present. Butrint started to reveal itself but under capitalism such academic research only continues if a monetary value can be placed upon it.

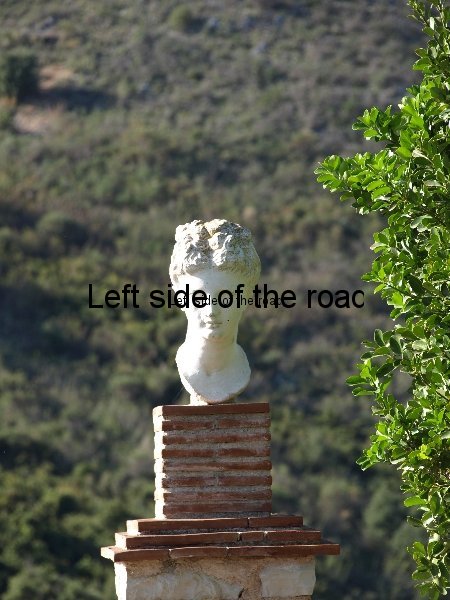

The small museum in the castle at the top of the hill is worth a visit. If it’s closed there will always be someone around who will open it up if asked. Here are displayed some of the artefacts found at the site.

One statement particularly attracted my attention when walking around the museum and this was in relation to the inscriptions about the freeing of the slaves down at the theatre. Many of the inscription refer to women who were freeing the slaves and were therefore wealthy and in control of that wealth themselves. It seems in the early Greek days, before what is now called the Classical period, women would inherit any wealth from their husbands, as well as being able to become wealthy in their own right. This position of women in society is considered an ‘advance’. The problem is I don’t believe the slaves would have been too concerned about the gender of their ‘owners’. And in that ‘advanced’ society this equality was still denied to poor women. It wasn’t until the liberation of the country from fascism in 1944 and subsequent years that women truly found a semblance of equality in Albania.

Practical Information:

The public bus leaves from the bus stop opposite the ruins of the basilica and synagogue, just along from the Town Hall (the Bashkia). It leaves, more or less, on the hour and half hour until midday and then on the hour for the afternoon and takes about 45 minutes. Cost is L100 each way.

Butrint is open from 08.00 till dusk, all year round. Entrance is L700 for an individual (although I was charged the reduced group rate, although by myself, of L500 the second time I went there).

More on Albania …..