Santa Creu i Sant Pau Recinte Modernista

The largest, and in many ways the most impressive, of the Modernist sites in Barcelona, indeed in all of Catalonia, is probably also one of the least known and visited. This is the Hospital de la Santa Creu i Sant Pau, designed by the architect Lluís Domènech i Montaner who was also responsible for the Palau de la Música Orfeó Català.

Although it’s always been possible to get an idea of the place (I first had the chance to walk around in the late 1990s) it was still used as a working hospital up to 2009 so access was limited to what you’d find in any hospital in the UK. Following its closure as a medical facility it has undergone a clean up and restoration and all I can say is that they have done a magnificent job – it looks as if it had just been completed rather than having the first stone laid on January 15th 1902.

The history of the hospital itself goes back a long way. The first Santa Creu (Holy Cross) was established in the Raval area of Barcelona with the foundation stone being laid on February 13th 1401. This became a large Gothic structure designed along the lines of an ecclesiastical cloister. However, after 500 years it was showing its age and not really up to the demands of ‘modern’ medicine and was also taking up space in the centre of an expanding industrial city. (The Raval area includes what is presently known as the ‘Barrio Chino’, for some a no-go area on the southern side of La Rambla, more or less the area behind the Liceo Opera House.)

The money to kick-start the development came from a bequest in the will of a Catalan banker, Pau Gil i Serra, who made his ill-gotten gains in Paris – it’s his statue that stands above the fountain on the steps up to the main entrance, with Charity looking after the sick and poor in front of him and huge frogs on either side (I don’t know what they signify). He stipulated that the hospital should take up the challenge of the rapidly increasing advances in medical science and also that it should be dedicated to Sant Pau (Saint Paul), so his name was added to the original Santa Creu.

There was a competition but none of the three submissions were considered adequate so the commission was given to Domènech i Montaner (obviously no hint of nepotism or cronyism there!).

By all accounts he did his research and studied what was happening in hospital architecture throughout Europe and came up with the arrangement which had separate pavilions, devoted to different aspects of medicine, and then connected them all together with an extensive underground passageway system, providing access without having to go outside. That idea has gone out of fashion now and most modern hospitals are huge all-encompassing buildings, few of them seeming to have been designed with a scintilla of imagination.

The complex seems vast now but it’s only just over half of what was in the original plan as Domènech i Montaner planned 48 buildings, only 27 were actually constructed. He died, in 1923, before even that number was completed and the work was continued by his son to make the hospital ready for its official opening in January 1930.

The jewel is definitely the main building on the corner of Carrer de Cartegena and Carrer de Sant Antoní Maria Claret. The building embraces the corner of the two streets and the approach is up the wide steps in the centre (with the statue and fountain). If you scan the façade of the building you start to notice those signature elements of Catalan Modernism: nature, the female form and Catalan nationalism as well as the use of the locally produced (then) building materials of brick, tiles, glass and wrought iron.

Once inside you’re greeted by intricate and colourful tile work which continues as you walk along the passageways and into the rooms off them. When there’s a natural break, a doorway or a corner, there’s a different style and/or colour. I’ve still not really understood why this all works. In other buildings (most notably the Palacio Real in Madrid or the Baroque Basilica de San Juan de Dios in Granada) when I’ve been faced with such extremes of ornamentation I’ve felt physically sick and have to leave to get some fresh air (or a beer) but that isn’t my reaction to Modernism. Something ‘softens’ the attack of colour and design and the overall effect becomes less of an assault on the senses.

The plan is to use the Administration Pavilion as an event/conference venue and that has meant that some of the spaces have been adapted for a future use but as far as I could see this had all been done whilst at the same time maintaining the integrity of the original designs.

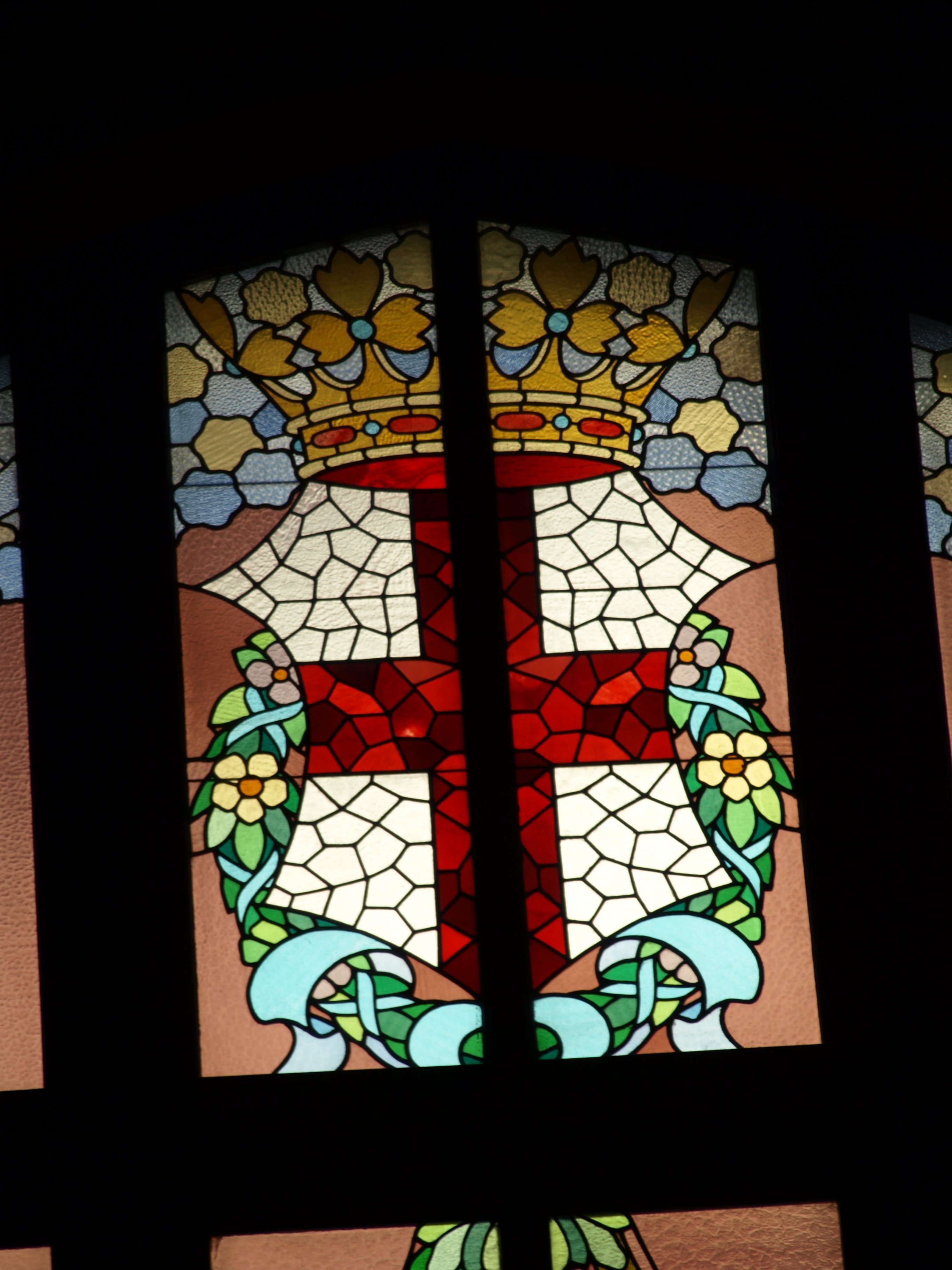

A couple of spaces are worthy of special mention. The first is what would have been the chapel which is now called the Montaner Hall. You really have to look for Christ as he’s on a cross on the back wall of a first floor balcony. There’s no obvious altar now so I assume that it would have been a table structure on the ground floor underneath that crucifix. There’s the words of a short prayer (in Catalan) forming the balustrade of the balcony on three sides of the hall; an image in relief of Sant Jorge (Saint George) slaying the dragon above one of the doors; and a large mosaic which is more geometric with stylized plants and flowers rather than anything religious – this mosaic is underneath the crucifix.

These mosaics, made from small pieces of ceramics and called ‘trencadis’ in Catalan, is very much a feature of Domènech i Montaner’s style of working. His style is much more in the tradition of the Roman mosaics where it’s possible to discern an image, be it of a plant, decorations on columns or pictures of choristers (as it is in the Palau de la Música). On the other hand Gaudí’s style was to break the tiles into larger pieces and creating a colourful design without necessarily wanting to represent anything identifiable – as is the case on the benches in Park Güell. His use of the smaller pieces on the Dragon on the fountain is to create colour rather than form as the creature is made out of stone onto which the tiles are fixed.

The other area of special note is the main stairwell immediately to the left as you enter the administration building. Here the supporting arches are covered with ceramic tiles and the spaces in between contain geometric mosaics made again by smaller pieces of, this time, white and beige tiles. Also interesting here is the skylight that’s very reminiscent of ‘The Sun’ above the main auditorium of the Palau de la Música. The large wrought iron lamp on the banister half way down is also a one-off in the building.

In order to get to the other buildings you head down into the basement and then along part of the network of underground passageways that unite all the separate parts of the original hospital. You can’t explore all of these as the pavilions that are out in the garden are either used by different organisations or have yet to be restored. Nonetheless you do get an idea of what Domènech i Montaner was aiming for, keeping all the servicing of the hospital’s requirements underground and creating the ability to get to all the pavilions without having to pass through or disturb any of the others.

Once outside the main administration building it’s easy to see why Sant Pau was sometimes referred to as a ‘garden hospital’. In fact, if you didn’t know the different buildings were part of a medical complex you would be hard pressed to come to that conclusion. Used, as we are now, to generic, functional and normally boring and uninteresting structures where we go to have our medical requirements fulfilled (the new hospital in Reus being a noteworthy exception to this ‘rule’) the buildings seem to be more like homes for the rich than wards and laboratories.

Although I find their exteriors fascinating I wouldn’t have liked to have spent any length of time either working in them or being a customer (what used to be called a ‘patient’). Photographs of the wards make them seem cold and austere, however much they might have been ‘state of the art’ on their completion in 1930.

Only a few of the buildings have been fully restored and now have a new lease of life as offices for different organisations that look for attractive pictures to put on their publicity. When I visited it was part of the open days and some of these organisations allowed people to look into their space but I assume that on a regular basis it would only be the outsides that are part of the tour. But the outsides are enough and stylised plants and fruit made from colourful tiles sits well with the orange trees below.

Also worth looking for whilst out in the garden are the different mosaics which decorate the sides of some of the pavilions. There are a couple of Sant Jorge and also (just above the entrance to the obligatory souvenir shop cum exit) depictions of the planning of the project and the laying of the first stones.

At the moment only eight of the buildings have been fully renovated. The initial plan, for which a budget of €100 million has been allocated, takes in 12 buildings and they are those around the central building of the garden as well as the administration building itself. That still leaves 15 (assuming they have all survived into the 21st century) and some of them are very large indeed so whether the finance will be there in the future must be in some doubt. The present funding was secured before everything went down the pan and we are now rewarding the bankers with ever-increasing bonuses means there’s less for other projects.

I’ll finish this introduction with a couple of anecdotes.

During the Spanish Civil War the hospital was taken over by the Republican local government of Barcelona. As in all civil wars things get dirty and the antagonism between the Catholic Fascists of Franco and the atheist Republicans was intense. Church buildings were burnt by the Republicans and Catholic Priests blessed and gave absolution to the Fascists as they murdered those who were fighting in defence of the legitimate government. So it’s no surprise that this had an effect on the hospital.

The religious name was changed from Santa Creu I Sant Pau to the General Hospital of Catalonia. All the pavilions had been given religious names based on Saints and the Virgin Mary (as they are now) and these were replaced by numbers. This was the case until February 9th 1939 when matters reverted to the pre-war condition with the entry of the Fascists into the city of Barcelona.

The young Pablo Picasso was friendly with one of the surgeons of the hospital and for some reason when he went to Sant Pau to meet his friend in 1903 they decided to visit the mortuary. A women that he saw there inspired Picasso to paint La Dona Mort (The dead Woman) which is an example from his ‘Blue Period’.

Although the queues were literally around the block between February 25th and March 16th, 2014 when it was free to enter as a celebration of the completion of a significant part of the restoration the Sant Pau Recinte Modernista (as it is now called) still hasn’t got into the guide books and won’t be attracting the same crowds as other Modernist sites in the city. It’s still possible to get tickets at very short notice so go there soon before it gets swamped. As the plan is to make money from the likes of conferences and exhibitions in the newly renovated space you would be well to check the news section on the website to make sure access is possible when you might want to visit.

Location:

Sant Pau Art Nouveau Site

C. Sant Antoni Maria Claret, 167

08025 Barcelona

Website:

How to get there:

Metro (L5): Sant Pau / Dos de Maig

Visits:

SELF-GUIDED

Cost and Timetable:

General: €8

Over 65, Aged 16-29 and Disabled: €5.60

Under 16: Free

November – March

Monday to Saturday 10.00 – 16.30

Sundays and holidays 10.00 – 14.30

April – October

Monday to Saturday 10.00 – 18.30

Sundays and holidays 10.00 – 14.30

GUIDED

Cost and Timetable:

General: €14

Over 65, Aged 16-29 and Disabled: €9.80

Under 16: Free

November – March

Monday to Saturday 12.00, 13.00, 16.00

Sundays and holidays 12.00, 13.00

April – October

Monday to Saturday 12.00, 13.00, 16.00, 17.00

Sundays and holidays 12.00, 13.00

Closed:

1st and 6th January, 25th and 26th December

Free:

25th January, 12th February, 23rd April, 24th September, first Sunday of the month

Book Online HERE