Lenin and October Revolution Monument in the Kaluga Square – Moscow

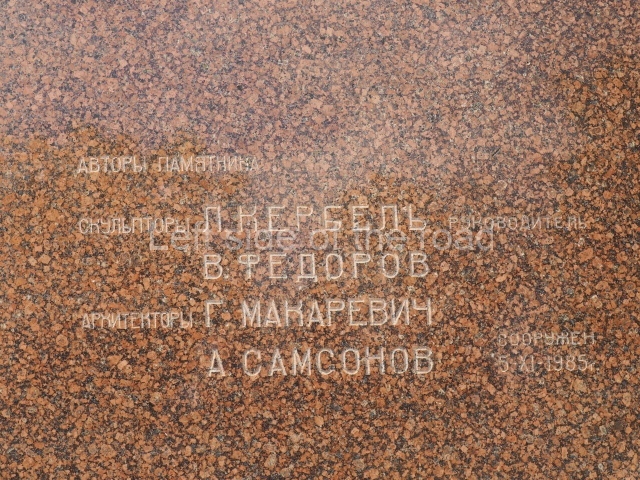

The Monument to Lenin on Kaluga Square (Russian: Памятник Ленину на Калужской площади) was established in 1985 in Moscow in the centre of Kaluga Square (then October Square). The authors of the monument are the sculptors L. E. Kerbel, V. A. Fedorov and the architects G. V. Makarevich and B. A. Samsonov. It is the largest monument to Lenin in Moscow.

The bronze sculpture of V. I. Lenin was made at the Leningrad factory ‘Monument sculpture’. It is an original copy of the monument to Lenin in Birobidzhan, established in 1978. A stone monolithic pedestal column weighing 360 tons, after the initial treatment, was delivered in place by a trailer that had 128 wheels. The monument was inaugurated on 5 November 1985 by the General Secretary of the CPSU Central Committee, Mikhail Gorbachev.

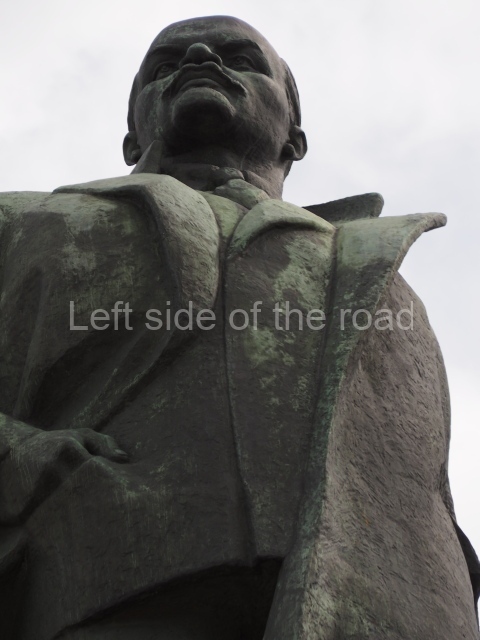

The height of the monument is 22 m. At the top of the cylindrical column of red polished granite is a full length bronze statue of V. I. Lenin. He is facing forward, his gaze to the distance. Lenin’s overcoat is unbuttoned, one lower edge is thrown back by the wind, his right hand is in the jacket’s pocket.

At the base of the pedestal is a multi-figure composition, which includes revolutionary soldiers, workers and sailors of various nationalities. Above them is a woman on the background of a fluttering flag embodying the Revolution. Behind the pedestal is the figure of a woman with two children, personifying the rear of the revolution. The elder boy in his hand has revolutionary newspapers.

Text above from (a slightly edited page on) Wikipedia.

What to look for in the monument;

- the three leading figures are, from left to right, a peasant soldier, an armed Petrograd worker, a sailor;

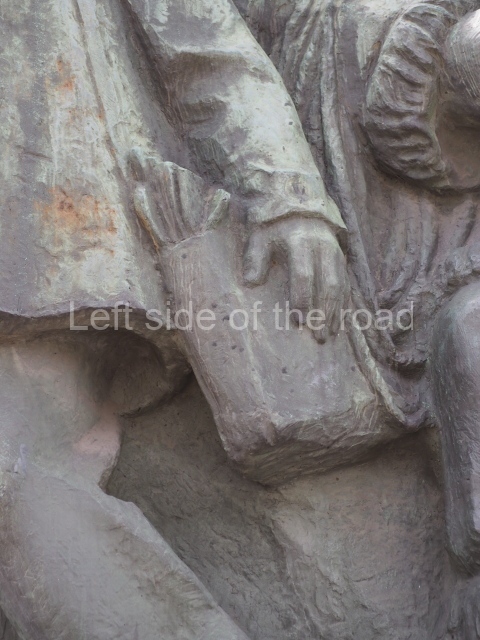

- the peasant soldier wears a knotted red ribbon over his left chest – the red arm band was the normal sign of a Bolshevik but this is difficult to represent on a bronze statue. Whether the red ribbon was an alternative ‘badge’ I’m not sure;

- the female representation of Revolution, that is located above the revolutionary workers and peasants and below Lenin. She has her right arm raised forward and upward – indicating the advance of the revolution – and her left arm stretched behind her I a pose that invites others to join the march to the future. Her flowing scarf is a representation of the Red Flag, the workers’ revolutionary standard;

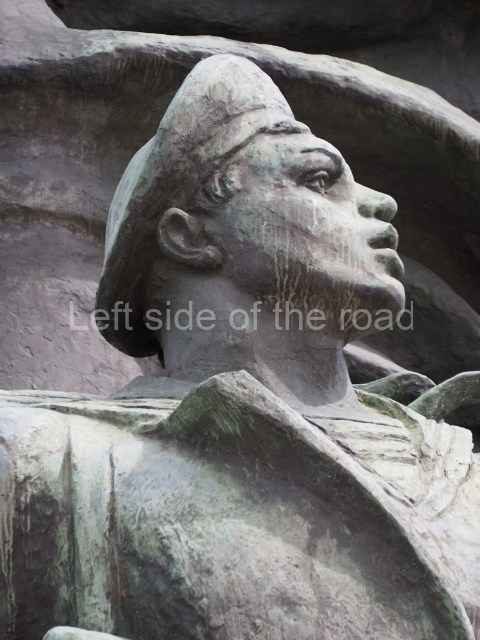

- the leading sailor (note the striped t-shirt under his jacket) also has his left arm stretched behind him, also encouraging those (unseen) behind to come and join the revolution, he’s also looking in their direction. He, and the female sailor on the other side of the group, were probably from the Cruiser Aurora;

- the older workers/peasants indicating that the revolution is not just a matter for the young, their dress suggesting that they are possibly from other nations in the old Russian Empire and stressing the All-Russia aspect of the October Revolution;

- the engraving at the back of the red marble plinth which notes the sculptors and architects as well as the date of the monuments unveiling;

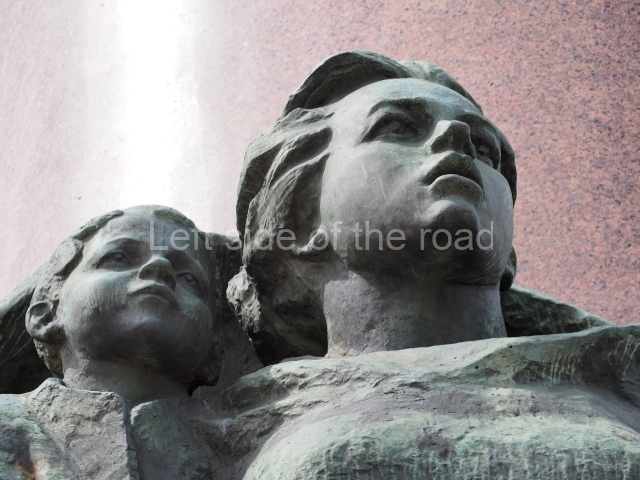

- the young mother, holding a very young child in crook of her right arm and her left hand on the shoulder of an older boy, representing for the new and youthful Socialist Republic that was being created following the attack on the Winter Palace;

- the young boy newspaper seller next to the young woman. He has copies of the newspaper Izvestia (which had been founded in February 1917 and which, at the time, was the mouthpiece of the Petrograd Soviet) folded over his right forearm and more copies in a satchel hanging from his left shoulder. The headline also indicates information about one of the first decrees of the Soviet Government, possibly that on Peace and an end to the imperialist war;

- another young boy who, from his looks and dress, comes from one of the many northern nationalities;

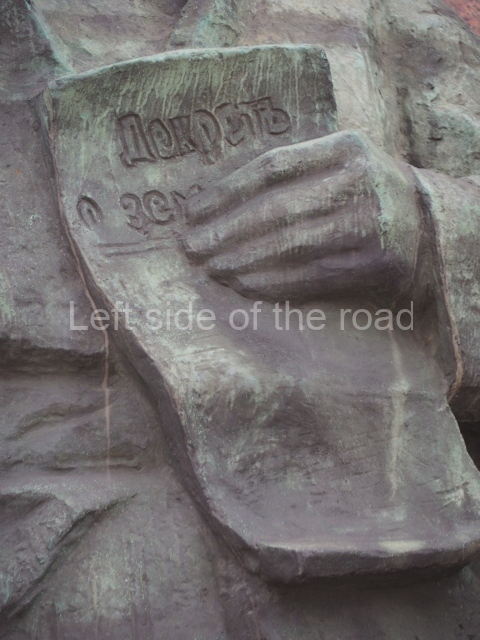

- the male peasant (again from one of the nationalities – note his turban type headdress) holding a copy of the Decree on Land – which nationalised all the land in the country;

- what looks like a female sailor (note the anchor on her belt buckle) who is armed with a pistol and wears a red neckerchief – but I have no information about women in the navy in pre-Revolutionary times;

- and surmounting all a full length statue of VI Lenin, leader of the Bolshevik Party (which became the Communist Party of the Soviet Union). He has an open overcoat over his suit, the right lower edge of which is being blown back by the wind. He is standing with his right hand in his suit jacket pocket and his cap is scrunched in his left hand. He’s looking ahead, in a contemplative pose, perhaps wondering what to do next and how to overcome the inevitable problems.

Not exactly sure what Lenin might have been looking at when the statue was installed in 1985 but now he looks down a long avenue towards the Moscva River – across which is the area know as ‘Moscow City’, an area of densely packed, ugly, modern high rise glass and steel buildings.

However, if Vladimir Ilyich looked slightly to his left he would be looking at the main entrance to the Okysbrskaya Metro station.

Sculptors;

L. E. Kerbel and V. A. Fedorov

Architects;

G. V. Makarevich and B. A. Samsonov.

Location;

In Kaluga Square (formerly October Square), at the junction of Lenin Prospekt and Krymsky Val, opposite the main entrance to Oktyabrskaya Metro station

GPS;

55.729466°N

37.613176°E