Mayapan – Yucatan

Location

Mayapan is situated 43 km south-east of Merida and 2 km south of the village Telchaquillo. The karst nature of the soil in the Mayapan region has given rise to rocky outcrops and natural depressions, cenotes (wells), caves and holes. The climate is of the hot sub humid variety with the rainfall occurring in the summer months and an average annual temperature of 22° C. The flora consists of deciduous trees and secondary low scrubland.

Pre-Hispanic history

The archaeological evidence suggests that Mayapan was inhabited from before the Common Era until the decline of the city around AD 1450. The data obtained is very general, indicating that people lived in or around the site from the Preclassic and Early Classic periods (300 BC-AD 600). Several stones used in the construction of new temples and residences have survived from the early periods. Mayapan experienced its heyday in the Postclassic period (AD 1050-1450), when it was the seat of a coalition government and the last great centralised capital that ruled over the provinces in the north-west and centre-north of the Yucatan Peninsula.

The first chronicler who mentioned Mayapan was Gaspar Antonio Chi. His father, the priest Napuc Chi, a dignitary of the Xiu, was murdered by Nachi Cocom in 1536; his mother was lx Kupil, of the Mani royal family. Gaspar Antonio was an informant of Brother Diego de Landa and wrote his own chronicle in 1582, where he mentions the importance of the Xiu family and the fact that the city fell in 1420. Around 1560, Brother Diego de Landa mentions that Mayapan was founded by Kukulcan (Quetzalcoatl) in the year Katun 13 Ahau (AD 1263-1283) – when Chichen Itza fell and was abandoned – who ruled for some time and then left for the centre of Mexico. The Chilam Balam notes the existence of a coalition government between Uxmal, Chichen Itza and Mayapan, nowadays known as the Triple Alliance. The archaeological excavations have not corroborated this entirely due to the chronological differences between the three sites: Chichen Itza and Uxmal both experienced their heyday prior to Mayapan. Around 1380, the main rulers decided to form a coalition government, which marked the beginning of a regime led by the Cocom family – as the richest and oldest lineage – until its defeat. The Xiu then arrived from the south and occupied the second position within the Mayapan government due to their diplomatic conduct and administrative expertise. The chronicles refer to the multepal or coalition government led by the Cocom, Xiu and Canul lineages, which occupied Mayapan the longest. Towards the middle of the 15th century, in the Katun 8 Ahau (AD 1441-1461), Mayapan was destroyed, burned and abandoned. The chronicles state that there was a battle to seize control of the walled precinct and dissolve the coalition government.

Site description

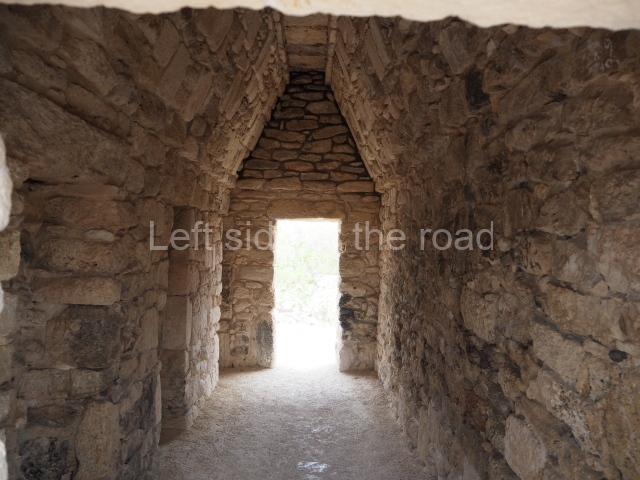

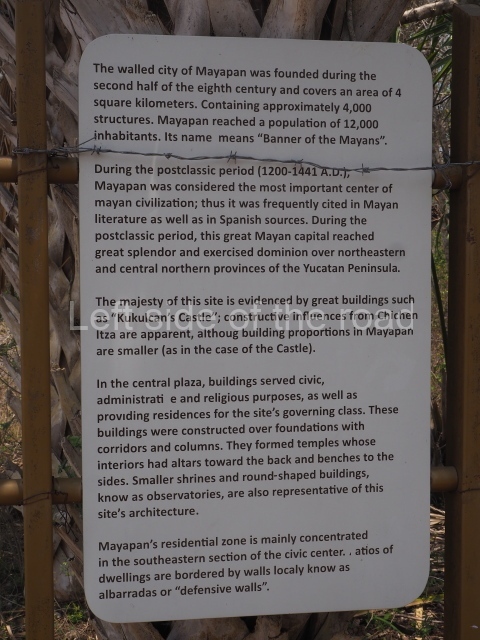

The city of Mayapan is surrounded by an elliptical dry wall which has a circumference of over 9 km and encompasses an area of 4.2 sq km; situated inside it are around 4,000 structures and it is estimated to have had a population of 12,000. The core area comprises the civic, administrative and religious buildings, as well as the residences of the ruling class; these are spacious hypostyle rooms, temples and oratories, constructed on platforms, with wide entrances divided by columns, an altar or shrine inside, abutted to the rear wall, and benches along the sides. Circular buildings known as ‘observatories’ are also characteristic features at Mayapan. Situated inside the walls is the residential area where the population lived, principally in the south-east section. This was the place where the ‘houses for the lords’ were built, ‘between whom they divided up the land, giving villages to each according to the antiquity of their lineage and nature of their person’. This section contains most of the housing and the dry walls that delimit the plots. There are also residential constructions beyond the perimeter wall where the common people lived.

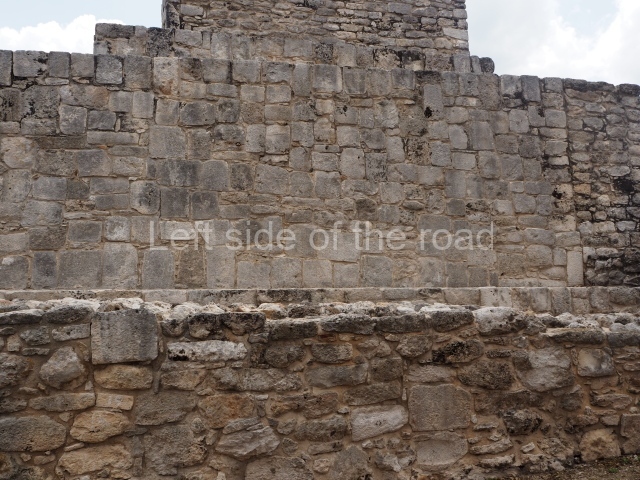

Castle of Kukulcan

This is situated on the south side of the Central Plaza and is the highest building at Mayapan. It adopts the form of a nine-tier echeloned platform with rounded corners, measuring 30×30 m and standing 18 m high. Each side has a stairway with balustrades. Atop it is a temple with a north-facing facade, the entrance of which consists of a two-column portico once decorated with serpents. There is a sub-structure at the south-east corner of the pyramid, with representations of decapitated warriors in moulded stucco. The discovery of fragments of human skulls inside the niches of the sub-structure confirm that it was used for placing stucco-covered heads, a practice associated with death worship.

Crematorium

The second-highest pyramid at Mayapan, this is situated on the west side of the North Plaza and is surrounded by a wall on three sides. The structure shows two construction phases comprising four sloping tiers with rounded corners, a temple at the top and a stairway with balustrades on the east side. The temple at the top has a triple entrance separated by two columns and there is a shrine inside. A tomb 7 m deep containing burials was found at the top of the platform. The building is 20 m long, 17 m wide and 8 m high.

Round temple

This is situated on the east side of the Central Plaza. It is a rectangular platform with moulding around the top and a balustraded stairway. It is 20 m long, 18 m wide and 3.5 m high. At the top is a circular, vaulted temple 10.20 m in diameter and 7.50 m in height, with four entrances and thick walls 1.15 m wide. The central part of the temple consists of a cylindrical volume 4.50 m in diameter with four niches in the lower section, two of which show traces of mural paint. This volume and the walls form the interior space, measuring 2.75 m in width and 6 m in height. There are also two small constructions – a small altar on a dais and a shrine – on the north side of the stairway.

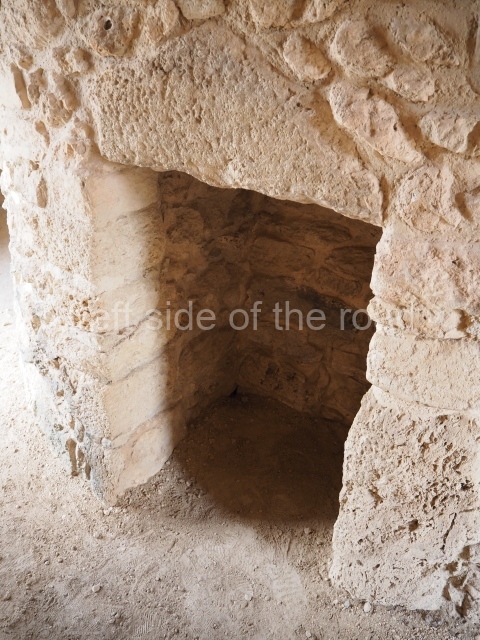

Temple of the painted niches

This is situated on the south side of the North Plaza and stands 7.50 m high. There is a stairway on the north side of the Plano de la Plaza Central de Mayapan: platform, built in two stages. The temple at the top is composed of seven rooms; two have niches inside and one of them has traces of mural paint depicting the facades of five temples, where the niches symbolise the entrances; the designs are outlined in black and painted in blue, red and yellow. The temples rest on serpent heads with open mouths, painted green, black, yellow and red.

Temple of the Fisherman

This occupies the north side of the North-East Plaza. The platform has sloping walls and a cornice on two of its four construction phases; it is 21 m long, 17.40 wide and 5 m high. The stairway leading to the temple is on the south side; the latter has a single bay with two pilasters at the front and a dividing wall. In the east room are two benches and an altar in the middle. The west bench contains traces of a scene depicting a human figure catching a lizard and fish.

Hall of the masks

Situated south of the Round Temple, the platform has a five-step stairway with finial blocks and an altar in the middle. The hall contains pilasters decorated with masks of the god Chaac, two rows of columns, two benches abutted to the walls and a shrine in the middle.

Fresco hall

This adjoins the lower sections of the east side of the Castillo. The building has columns on three of its sides and pilasters at the north-east and south-east corners; in the middle is an L-shaped wall with a bench on the north side and an altar in the middle. There are traces of paint on the central wall. The scene consists of red and yellow marks which frame richly attired figures in profile, painted red and yellow on a blue background. The figures hold a circular banner with representations of sun disks.

Hall of the kings

In this building the columns rise from an artificial platform at the south-west corner of the Central Plaza. There is a central wall with an intermedial entrance, a bench with moulding and pilasters at the corners. The excavations uncovered the stucco faces of the important personages that decorated the columns.

Temple of the Chen Mul cenote

Situated on the south bank of the cenote, this oratory displays a balustraded stairway and moulding along the top of the platform. The temple is fronted by a portico with three entrances formed by two columns, two pilasters, benches and an altar inside. On the north side of the building there is a sloping platform for rainwater to drain into the Chen Mul Cenote and a ramp leading to the Castillo terrace.

Temple of the warriors

Situated on the west side of the North-East Plaza, this is a two-tier platform with a temple at the top with three entrances and a shrine and altar inside. It is accessed via a balustraded stairway which culminates in finial blocks and serpent heads.

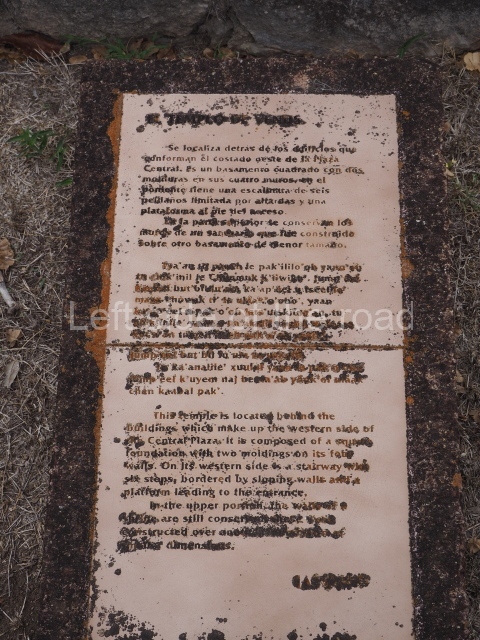

Temple of Venus

This is situated in the West Plaza of Mayapan. It takes the form of a square platform with two mouldings; there is a balustraded stairway and a shrine at the top.

Ceramics

Mayapan contains a wide variety of types and forms of ceramics. The most interesting are the effigy incense burners, which denote different decorative techniques to personify the gods. The pottery comprises finely made polychrome vessels as well as coarse monochrome pots for domestic use.

Importance and relations

This great Maya capital established in the second half of the 13th century was the most important centre of the Maya civilisation during the Postclassic period (AD 1050-1450), exercising its domain over the provinces in the north-west and centre-north part of the Yucatan Peninsula until just before the Spaniards reached the continent. The magnificence of the city is manifested in the grand and densely concentrated buildings. The architectural characteristics denote the strong influence of Chichen Itza. The main building at Mayapan, known as the Castle of Kukulcan, is a smaller version of the Castillo pyramid at Chichen Itza. Roys suggests that the Mayapan government was in some way associated with the island of Cozumel and Champoton. There is another walled site in the Chetumal region that existed at the same time as Mayapan, called Ichpaatun.

Carlos Peraza Lope

From: ‘The Maya: an architectural and landscape guide’, produced jointly by the Junta de Andulacia and the Universidad Autonoma de Mexico, 2010, pp 412-417.

1. Castle of Kukulcan; 2. Round Temple; 3. Temple of the Painted Niches; 4. Hall of the Masks; 5. Fresco Hall; 6. Hall of the Kings; 7. Temple of the Warriors; 8. Temple of Venus.

Getting there:

Bus station on Calle 50, near corner of Calle 67 in Merida. Buses leave 05.30, 07.30. 09.30. Drops you at slip road to site. M$30.

GPS:

20d 37′ 56″ N

85d 27′ 32″ W

Entrance:

M$70