El Mirador

El Mirador – Guatemala

Location

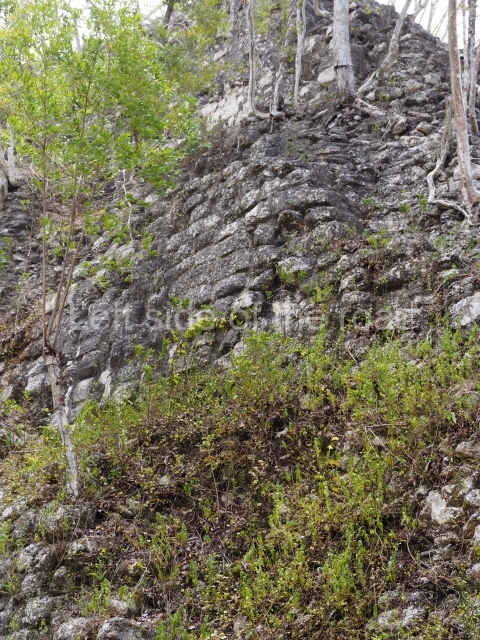

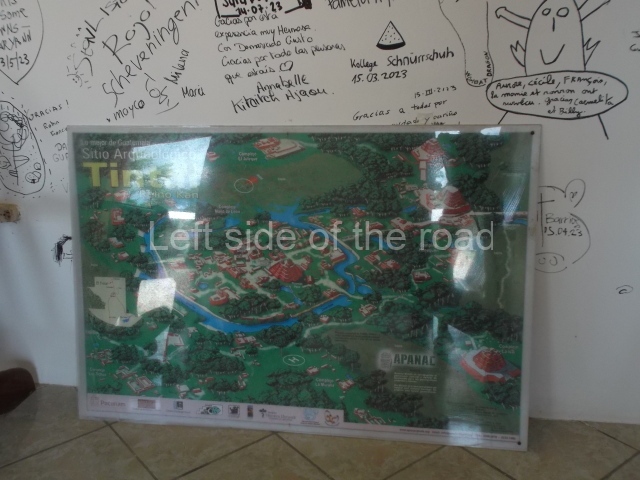

The archaeological site is situated within the cultural and natural boundaries of the Mirador Basin (2,066.71 sq km), an area protected by Decree 26-97 pertaining to the Protection of the Cultural Heritage of Guatemala. The basin lies in the northern section of the Peten region, very near the Mexican border and adjacent to the Calakmul Biosphere Reserve. This vast region encompasses 29 major archaeological sites and 50 smaller sites, constituting an ancient culture with some of the oldest cities in the Maya area. Its ecosystem – a karst topography of low mountains in the east and south, and less prominent in the west – is home to a rich variety of wildlife and plant species, with wooded uplands combining with plains and swamps. Nowadays, there are no towns or villages within the boundaries of the reserve, although several communities or human settlements emerged around the edges as a result of the chicle or gum industry in the early 20th century. The area does however comprise several forestry concessions: two industrial concerns and five community ones. The two communities closest to the archaeological area are Carmelita and Cruce La Colorada. A number of other communities, such as La Pasadita, Uaxactun, San Miguel La Palotada, La Colorada, Dos Aguadas, Ixhuacut and Caserio El Tigre, are encountered prior to Carmelita. El Mirador is situated in the municipal area of San Andres, in the Peten region. To reach the site, take the rough track from the city of Flores to Carmelita, approximately 85 km. The site lies 64 km from Carmelita and can only be reached on foot or by mule.

History of the explorations

The first reports of the archaeological sites of Nakbe and El Mirador date from 1926 and 1930, when their jungle-covered temples were photographed from the air by Percy Madeira as part of a larger aerial reconnaissance of Maya sites. In 1962, Ian Graham of Harvard University visited the two sites and drew up the first, albeit, partial maps. Four years later, Joyce Marcus dug a series of test wells on platforms, buildings and plazas at El Mirador, Porvenir, Pacaya, Guiro and Tintal. The ceramics recovered from these excavations were analysed by Donald Forsyth in 1978. Between 1978 and 1983 Brigham Young University and the Catholic University in Washington conducted the first systematic excavations and drew up a new map of El Mirador. Bruce Dahlin, Ray Matheny, Arthur Demarest and Robert J Sharer dug new test pits at the site in 1982. In 1987, R. Hansen organised the Nakbe Project and conducted the first archaeological survey of the site since Graham’s visit in 1962. In 1988 the Northern Peten Regional Research Project (PRIANPEG) was launched. This project contemplates systematic archaeological and ecological research throughout the region and encompasses major sites such as Nakbe, Guiro, Tintal, Naachtun and El Mirador, as well as the smaller sites of La Muralla, Porvenir and Pacaya. Since 1997 Richard Hansen has been leading one of the most ambitious and important projects in the Maya area, the purpose of which is to document the origins of the Maya civilisation.

Pre-Hispanic history

The earliest occupation of this region can be traced back to 1000 BC (Middle Preclassic). The oldest evidence corresponds to dwellings made out of perishable materials, with clay floors and post holes dug out of the bedrock. Richard Hansen has dated the boom in population to 700 BC, although the greatest period of development, marked by the construction of monumental buildings, occurred in the Late Preclassic. At the end of this period various events that have yet to be clarified led to the collapse and almost total abandonment of the sites in the region. This phenomenon was as dramatic as the sudden development a few centuries earlier. The latest evidence of occupation at this site corresponds to the Late Classic (AD 700-900), when a group of people built dwellings amid the imposing ruins of the abandoned city. However, these new constructions never achieved the monumental scale of the earlier ones.

Middle preclassic.

The ceramic remains suggest that the social hierarchy that emerged during this period was clearly linked to a strong agricultural base to maintain the increasing population. The pollen samples from this period indicate a strong presence of maize and pumpkin. Meanwhile, the enormous quantities of shell (Strombus pugilis) and obsidian confirm long-distance trade.

Middle and late preclassic.

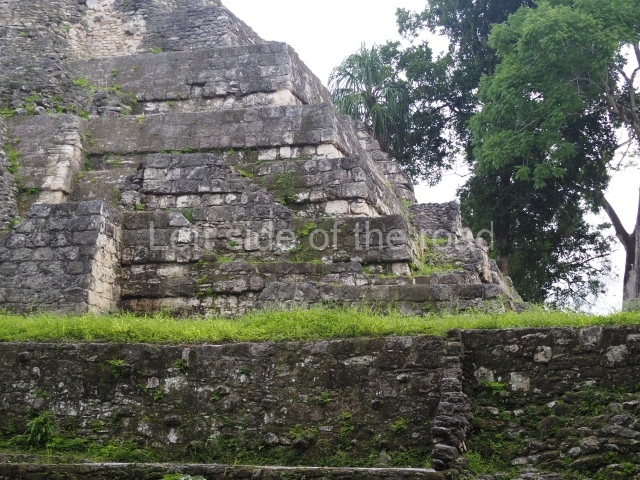

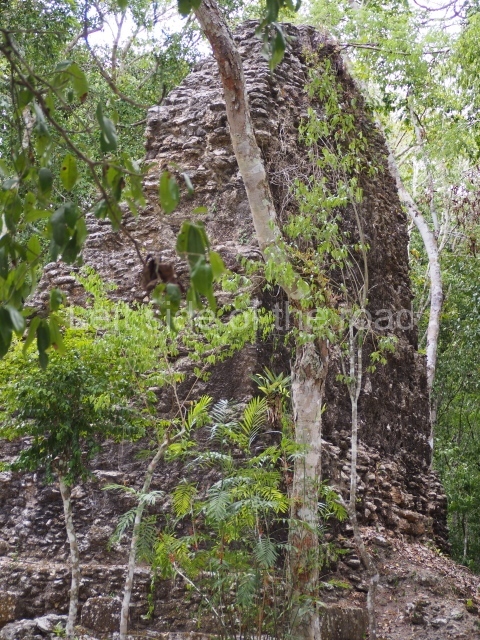

Nakbe, a nearby satellite town of El Mirador, experienced a boom in construction during this period, characterised for example by the colossal platforms built in both the East and West groups. At the beginning of the Preclassic, the entire Mirador region underwent radical transformations. The most spectacular of these was the new ‘monumentality’ of the architecture. Vast buildings such as the Monos, Tigre and Danta pyramids display extraordinary volume and height. The Tigre pyramid occupies 380,000 cubic metres and the Danta pyramid has over 1 million cubic metres of filling. This period was also marked by a new style and form: the introduction of the triadic pattern, which predominates in the majority of the architecture at El Mirador, Nakbe, Guiro and Tintal and can also be found at Uaxactun, Lamanai, Cerros, Calakmul and numerous other sites. Once it had taken root in the Late Preclassic, this architectural pattern dominated the entire Early Classic.

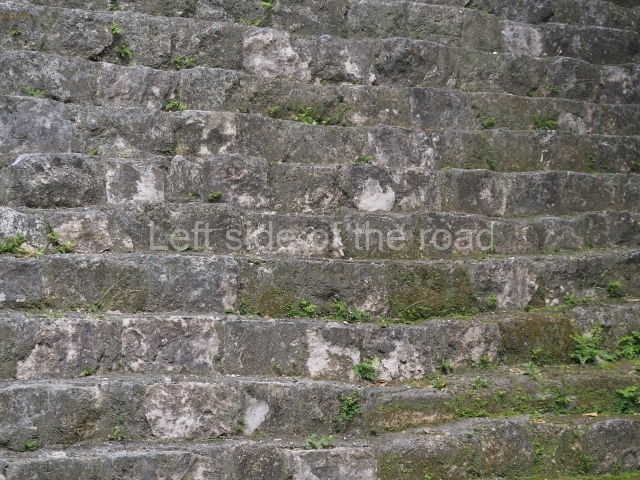

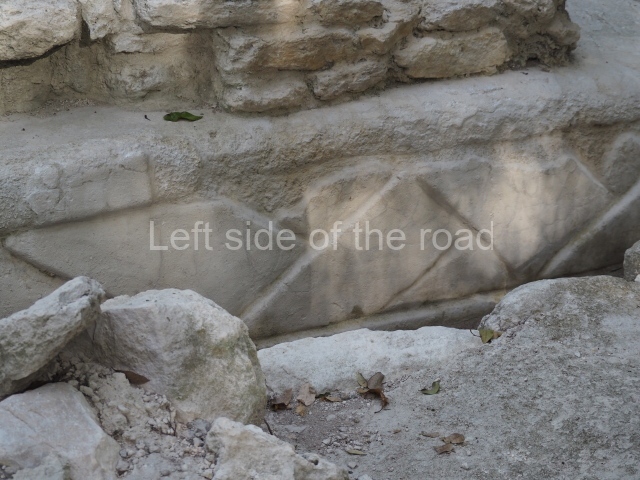

Between 600 and 400 BC, the Maya at Nakbe and Wakna changed their techniques and began to build much larger structures, great platforms rising to between 5 and 8 m in height, burying the evidence of the earlier occupation beneath tons of stones and filling. In many cases, the platforms were built out of large stones arranged in rows, one on top of the other. Sometimes, however, the stones were used to create a paved floor for the top of the platform, providing a base for the construction of larger buildings. There were also cases where the platform floor did not extend down the stairway of a building, indicating that planning had gone into the construction of the platform and the building.

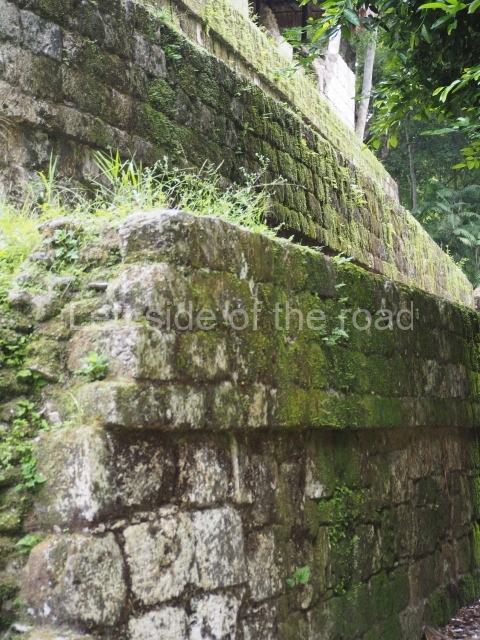

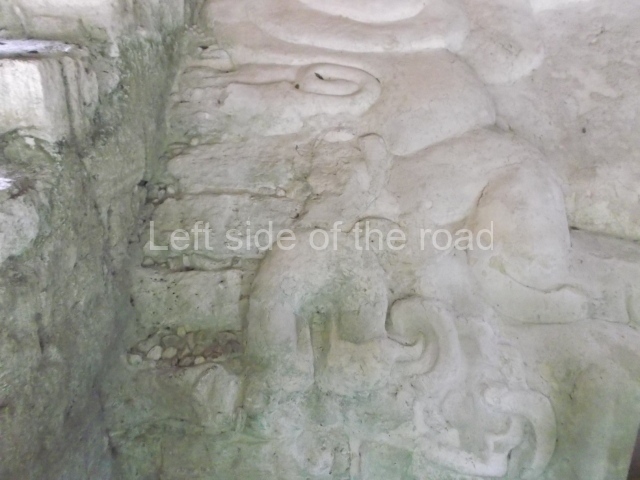

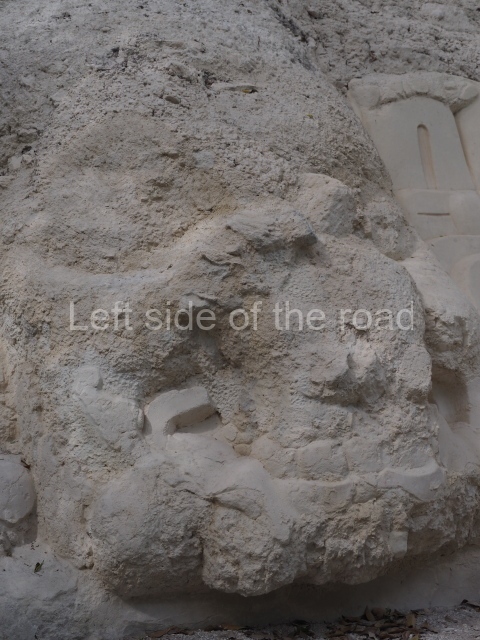

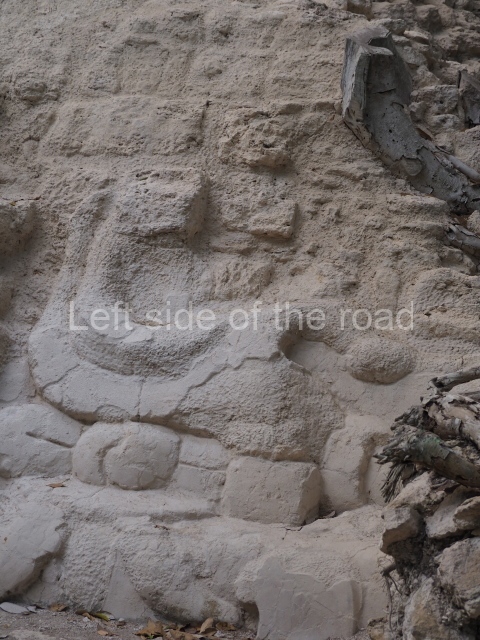

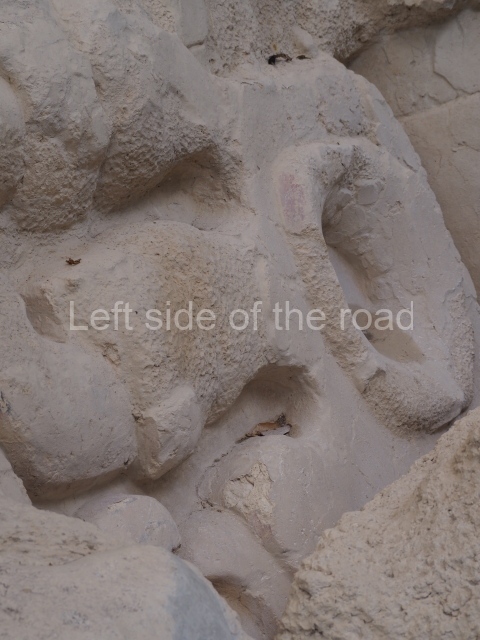

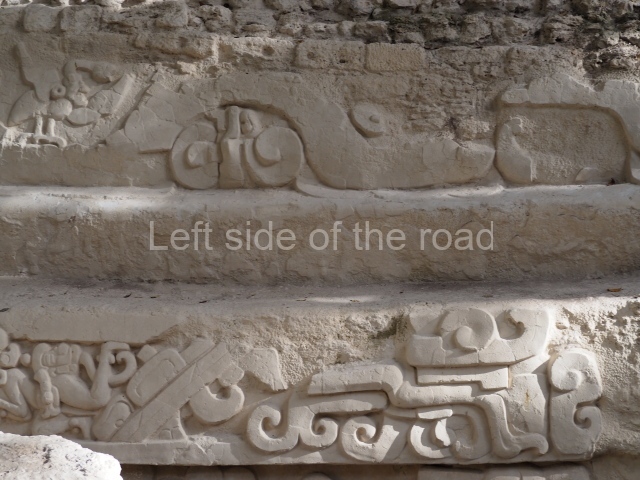

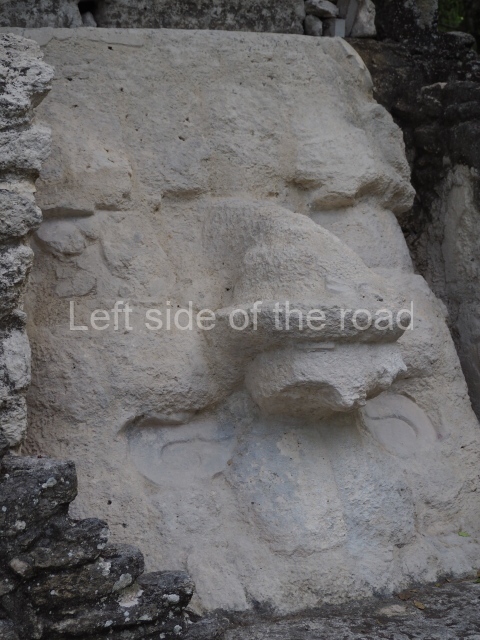

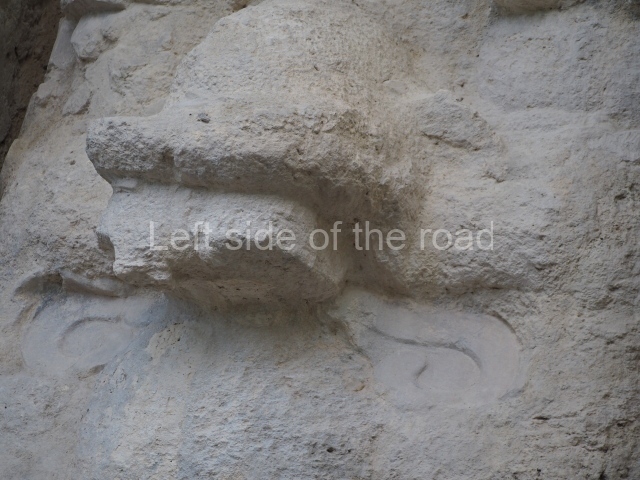

The Preclassic architecture at the sites in the Mirador Basin, and at El Mirador in particular, is characterised by the use of large blocks of limestone covered with thick layers of lime stucco and painted red (with ferrous oxide pigments). In the main buildings and temples, the central stairways are decorated with panels of masks. The ‘wall’ construction technique – crudely fashioned walls constructed internally on several levels to contain the loose fill of a building – was also widely used during the Middle Preclassic. These walls became quite elaborate, with different angles being used to form adjacent ‘cells’. This technique permitted higher vertical construction and indicates that by the Middle Preclassic sophisticated building methods were already being used in the lowlands. Another innovation in this period was the introduction of apron mouldings in which bevelled blocks projected from the internal wall, forming a cornice that protected the wall below. Sloping walls, resembling finely cut blocks, now began to replace the vertical walls of earlier periods.

There is ample evidence of significant changes in the landscape to control, store and channel water supplies, which were vital for the city. The excavations around the largest buildings at Nakbe have revealed networks of channels for managing water. The lack of aguadas or natural depressions in the Mirador Basin required greater efforts during the dry season to meet the needs of the growing population.

But perhaps the most notable constructions of this period were the causeways, the carefully planned routes with smooth floors, walls and parapets that linked the different cities in the area. These causeways could be up to 24 m wide and in certain places stood 4 m high and were several kilometres in length. All the major causeways that have been researched at El Mirador, Nakbe, Tintal and Wakna were in use during the Late Preclassic. This network of early causeways clearly facilitated the trade of goods, labour and food, and nowadays it provides us with clear evidence of the degree of political complexity in the region from a very early date.

Early classic.

Unlike the situation at other places in the lowlands, Mirador appears to have had a very small population in the Classic era. According to Hansen, this was the result of environmental degradation and the impossibility of sustaining large populations. The only evidence from the Early Classic comes from a small mound on top of the platform in Structure 18 in the West Group at Nakbe.

Late classic.

The greatest manifestation from this period can be found in the mounds, approximately 3 m high, situated around the civic precinct. The residential mounds and largest architecture in the north-west section of the site are known as the Codex Group because of the vast number of vases in the Codex style found in this elite group by looters.

Site description

El Mirador comprises two large architectural groups: the East Complex – comprising the Puma Group pyramids, the Guacamaya Group and the Danta Group (72 m high) – and the West Complex with the Cascabel Group, the Monos Pyramid (48 m high), El Tigre (55 m high) and the Leon Group. There are also outlying residential groups such as La Muerta and El Pedernal. These architectural groups cover a total area of approximately 25 sq km. The two large complexes occupy nearly 4 sq km and are situated in the city centre, next to the Acropolis and other important temples, terraces and numerous domestic plazas, all connected and delimited by a system of walls and raised causeways.

The east complex.

The predominant architectural design in the Mirador area during the Preclassic is known as the Triadic Pattern, which consists of a main building flanked by two, usually smaller, buildings. This design was reproduced to scale as the density of each complex increased. The East Complex at El Mirador comprises a massive architectural sub-group, known as La Danta, composed of a series of colossal platforms or tiers culminating in a summit temple. The base platform measures 350×600 m and stands 7 m tall; it supports several buildings, including a large triadic pyramid known as La Pava – the largest architectural construction in the whole of the Maya area. Recent excavations indicate that it was built during the Late Preclassic (AD 180 according to the radiocarbon date).

The west complex.

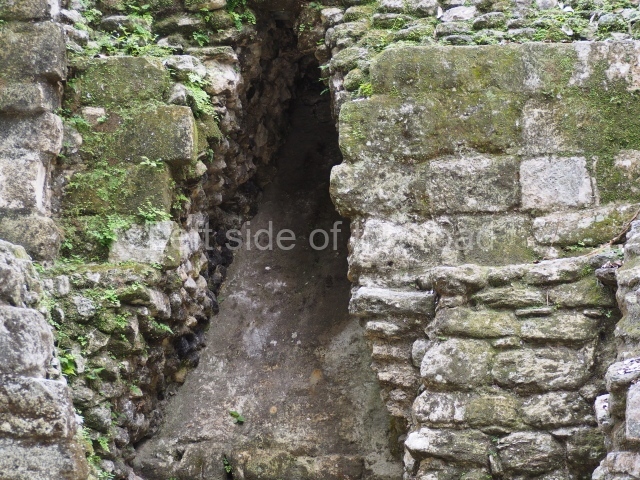

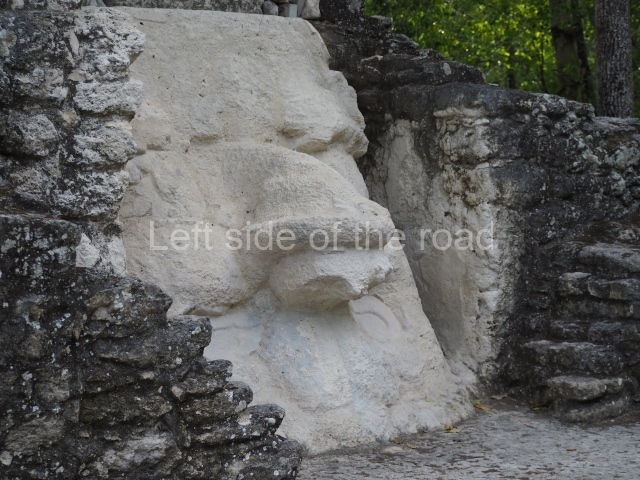

This comprises a plaza around which stand the Tigre Group and the Central Acropolis. There are three additional groups on the edge of the complex: Cascabel, the acropolis known as the Monos Group, and the Three Micos Group. The latter group adjoins the defensive wall, which has several entrances. This east side of this complex is delimited by a masonry wall that runs north-south, linking it to the little known Three Micos Group situated to the south-east. In 1982 the excavations conducted on this boundary wall indicated that it had been built in the Late Preclassic. The same excavations also revealed a sculpted monument or fragment of lintel (reused as a wall stone), which seems to come from the top of a Preclassic stela. The complex is dominated by the Tigre Pyramid, which covers an area six times larger than Temple IV at Tikal. There is also a triadic platform (Structure 34), whose stairway is flanked by 3-m-high masks. This is an acropolis type of platform and is surmounted by three temples. The deepest archaeological deposits found at El Tigre have been dated to 300 BC.

Central Acropolis.

Situated immediately east of the Tigre Group, this comprises several buildings, including an elite residence from the Late Preclassic. Construction of the Central Acropolis would appear to have commenced during the Middle Preclassic, although most of it corresponds to the Late Preclassic. As in many other precincts at the site, there is also evidence of constructions from the Classic era.

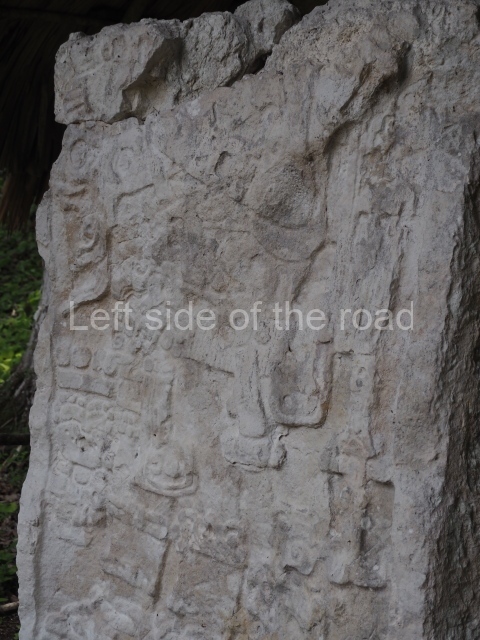

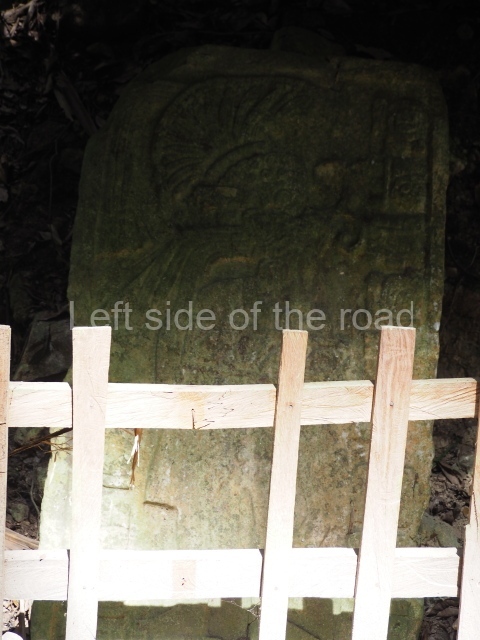

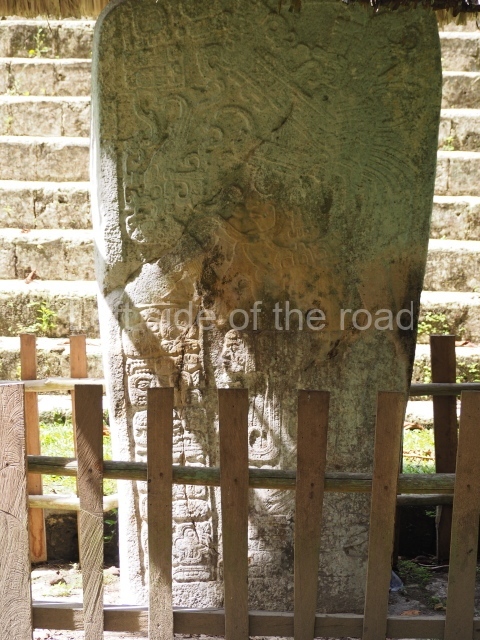

Monuments

The sites in the Mirador Basin boast a variety of sculpted monuments representing ancestral deities. These basically take the form of high reliefs on stelae and stucco-modelled masks flanking the stairways on the main buildings. One outstanding construction difference between the nine masks discovered at Nakbe is that they were carved in stone and then stuccoed. Most of the Preclassic monuments found in the Mirador area were transferred in the Late Classic from their original position to platforms and residential mounds, but the style, shape and archaeological context leave no doubt that they are much older. To date, the oldest monuments correspond to the Middle Preclassic. The most important sculpted monument is Stela 1 at Tintal, whose analysis indicates that it originated in the Altar de Sacrificios area. The stone weighs at least 6.42 tons and was transported from the confluences of the rivers Pasion and Usumacinta to Tintal, a distance of 110 km.

Rodrigo Liendo Stuardo

From: ‘The Maya: an architectural and landscape guide’, produced jointly by the Junta de Andulacia and the Universidad Autonoma de Mexico, 2010, pp236-239

How to get there:

The only way is on an organised tour as access to the National Park is restricted to those who have passed through the community of Carmelita, the closest public road access to El Mirador (and the other sites in the area). The Carmelita Cooperativa have an office in Flores on Calle Central América. In 2023 the cost of a 5 day, 4 night tour was Q2,800.

GPS:

17d 42′ 55″ N

89d 58′ 18″ W