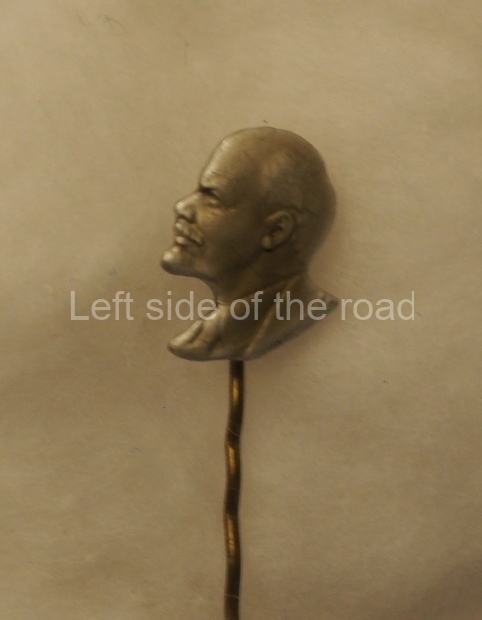

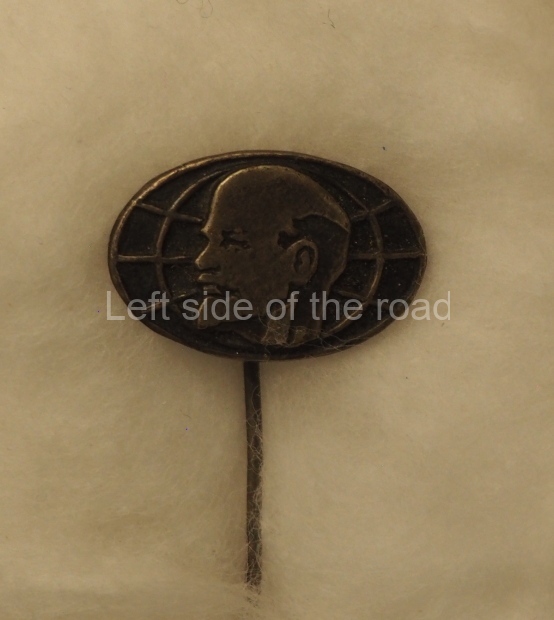

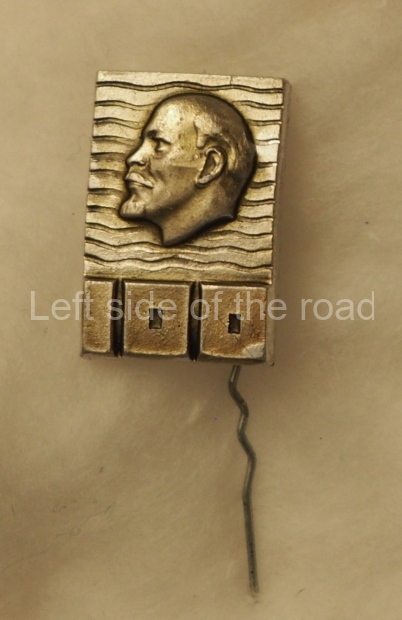

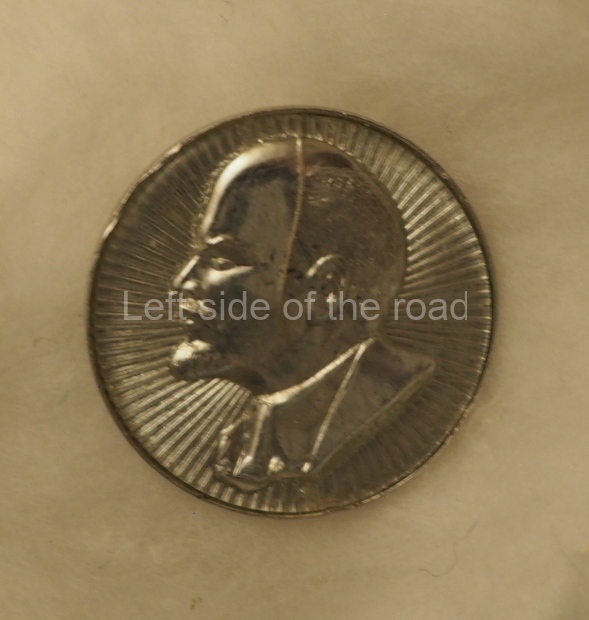

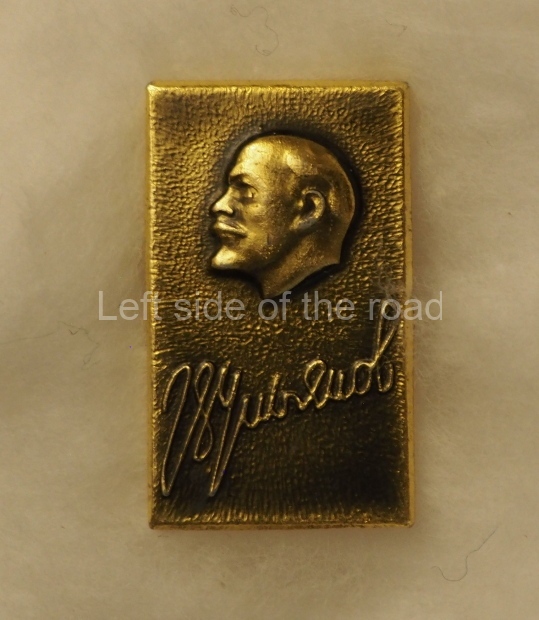

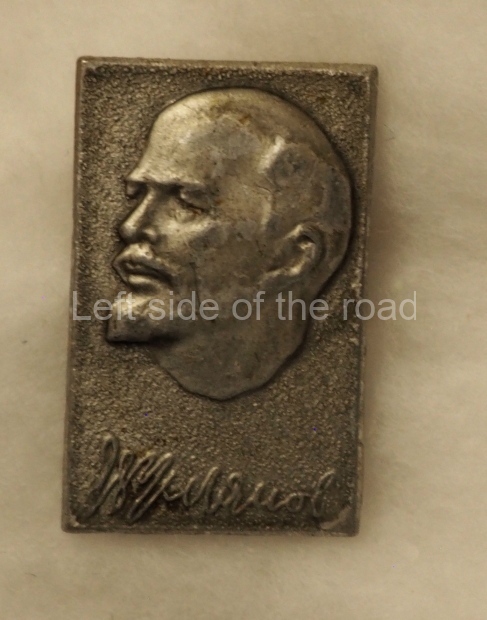

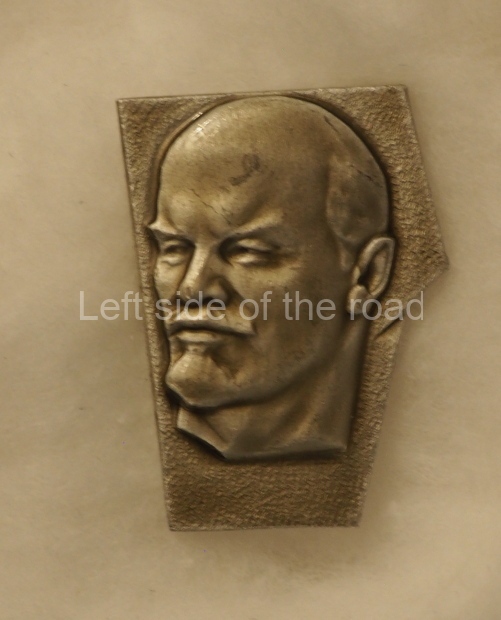

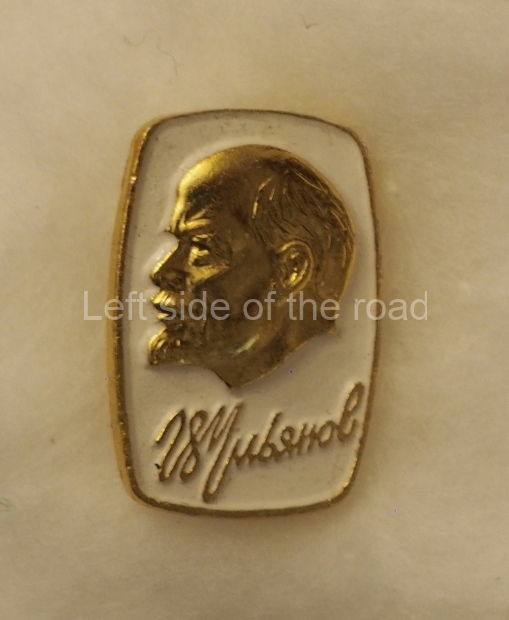

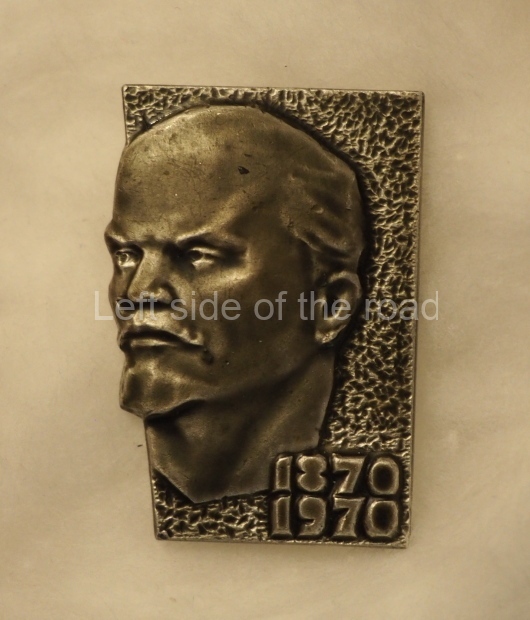

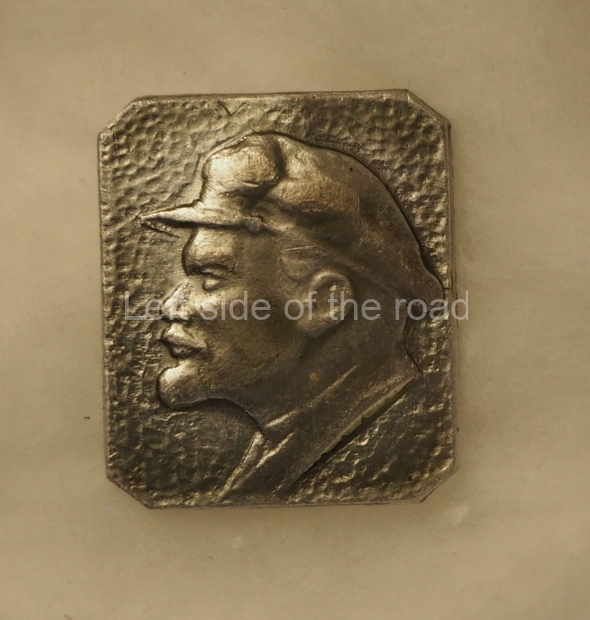

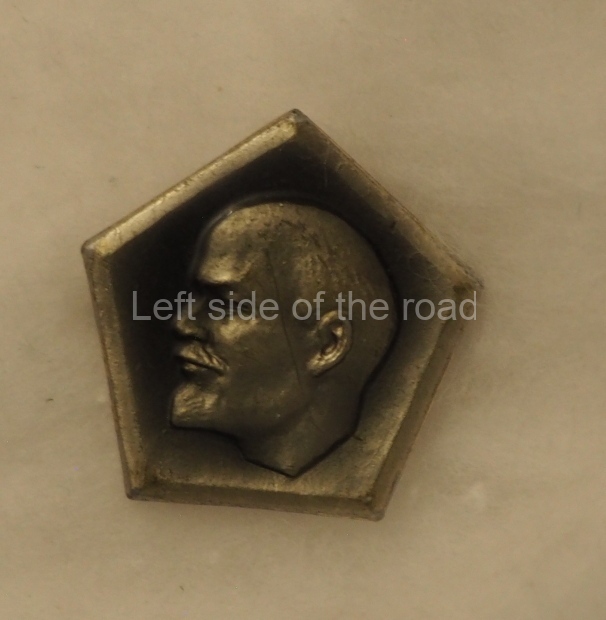

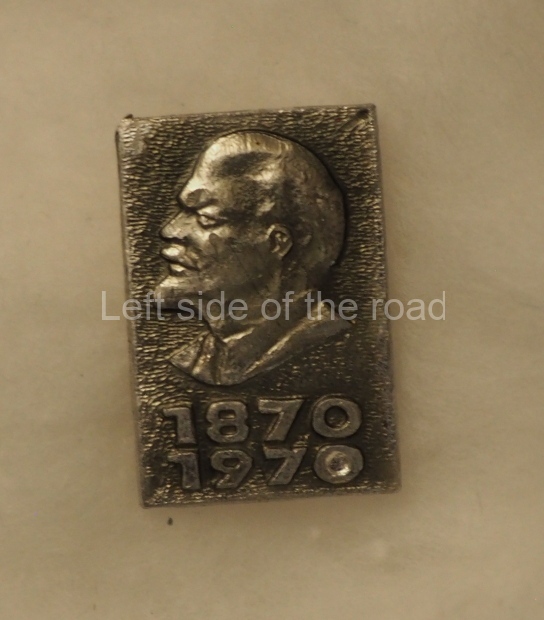

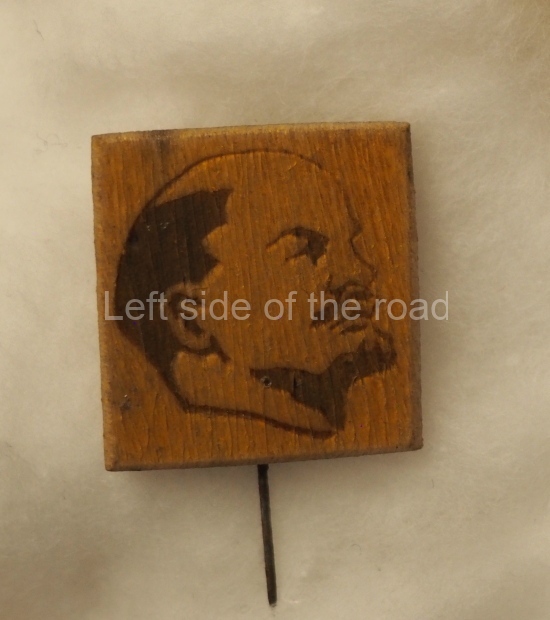

VI Lenin badge picture gallery

I don’t really know when the wearing of badges with the image of VI Lenin started to become common place in the Soviet Union.

Images of the first Bolshevik leader were used soon after his death, especially in photo-montages, for example, promoting the scheme of the ‘Electrification of the whole country’. The Soviets had long understood that in a (at that time but quickly diminishing as literacy campaigns took root) predominantly peasant country with high levels of illiteracy that the visual image – especially in the form of cheap to produce posters – were an effective weapon to get over the government’s message. This was later stepped up during the 1930s with the programmes of collectivisation of agriculture and the industrialisation of the country in the Five Year Plans.

Yes, this was propaganda – but which society before or since hasn’t used all the methods to hand to get across their message?

Also, in the 1920s images of Vladimir Ilyich would have been common in state and public buildings. (This happens in the present day in the USA where there’s always an image of the present President in public buildings down to and including post offices – so not a uniquely Soviet phenomenon.) However, I don’t know to what extent this practice would have developed in private houses.

(In the Democratic People’s Republic of Korea you will find the image of Kim Il Sung and Kim Jong Il in virtually every home – normally the two of them side by side. However, I have never seen an example where the image of the present leader (Kim Jong Un) is on display in either a public or private forum. It is almost virtually impossible for foreigners to acquire a badge similar to those which every citizen wears in public.)

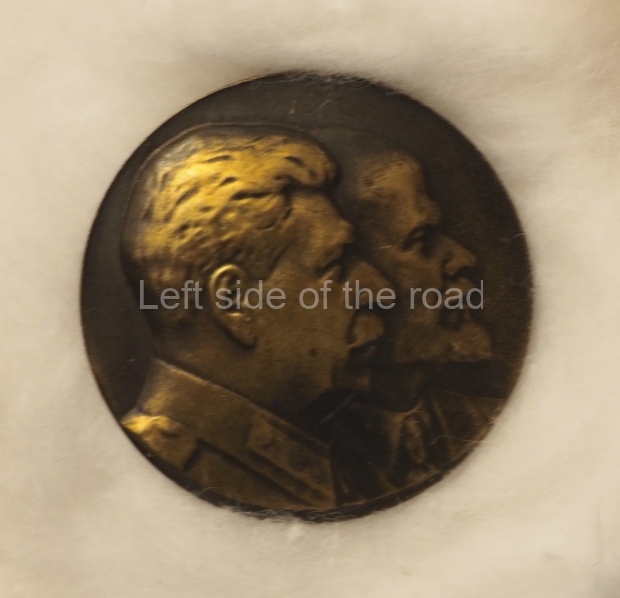

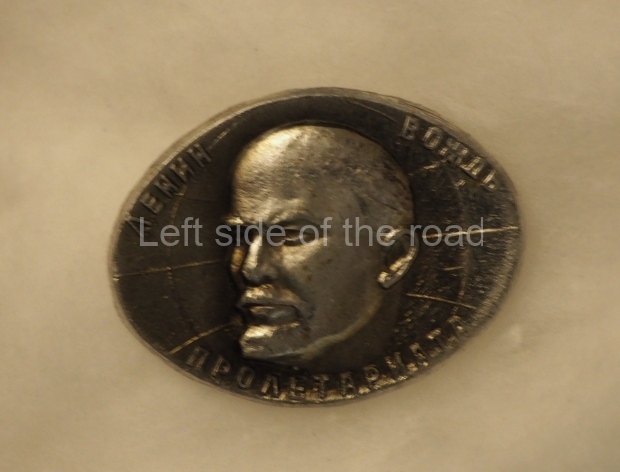

Returning to the Soviet Union I have not come across any badges with the image of Soviet leaders (and here I’m talking principally about VI Lenin, JV Stalin and FE Dzerzhinsky – the only three I have seen personally depicted on a badge – I’m ignoring here the traitorous Gorbachev and the vodka sodden idiot Yeltsin) prior to the 1970s. If there have been personal badges earlier they tended to be of a Red Star or a Hammer and Sickle – and from the early days the Hammer and Plough. But nothing of the leadership.

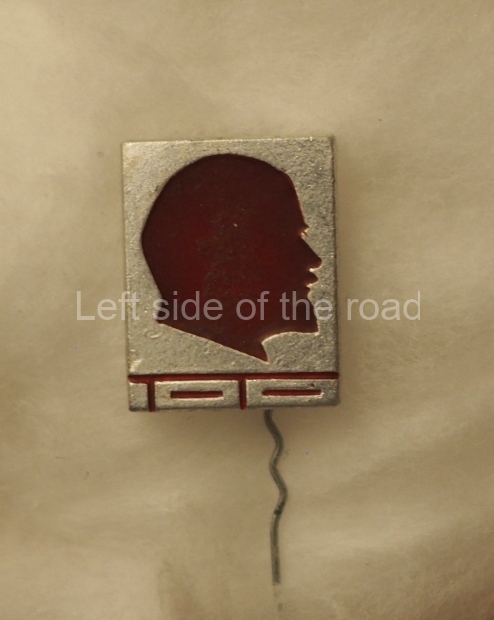

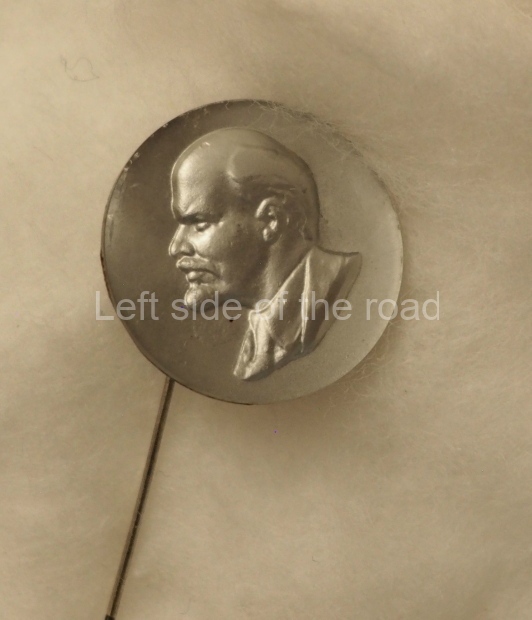

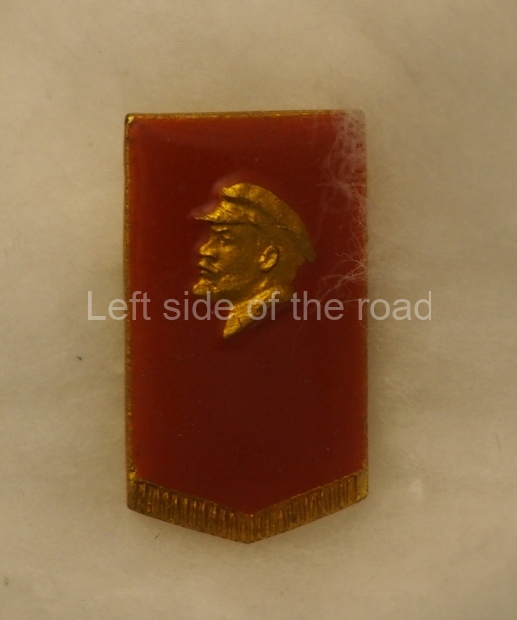

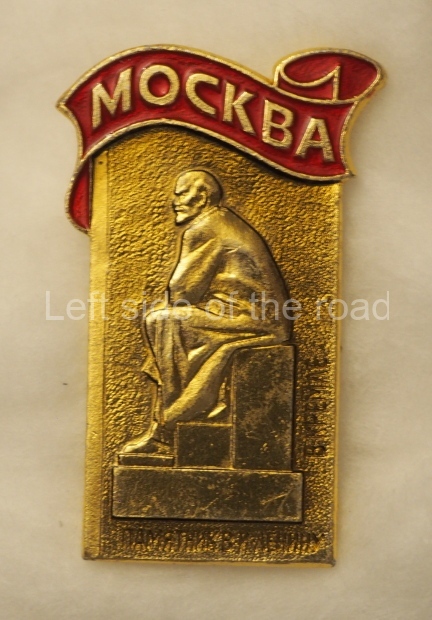

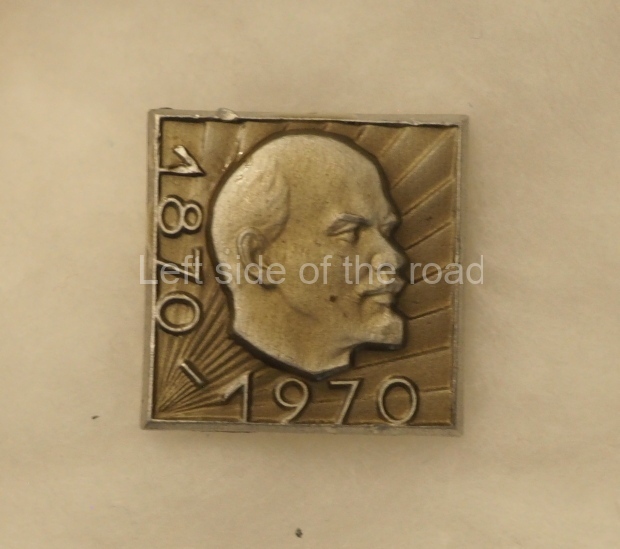

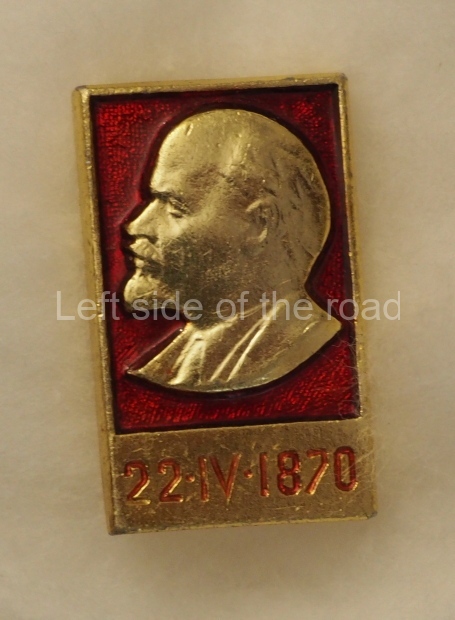

1970 saw the hundredth anniversary of the birth of VI Lenin – and many of the badges produced made direct reference to that anniversary. My assumption is that in an effort to boost their credibility (and to piggy-back on the admiration the people of the Soviet Union had for the first Bolshevik leader) the then Revisionist leaders of the Communist Party of the Soviet Union instigated the wearing of a small badge with Lenin’s image. It must be remembered that this was only a few years after the beginning of the Great Proletarian Cultural Revolution in the People’s Republic of China which included the wearing of a badge with the image of Chairman Mao.

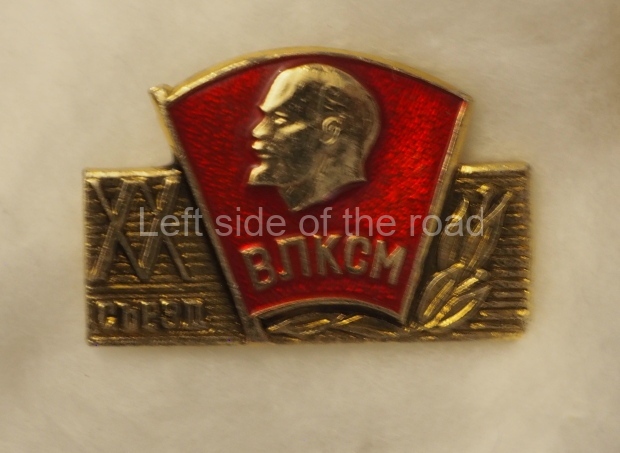

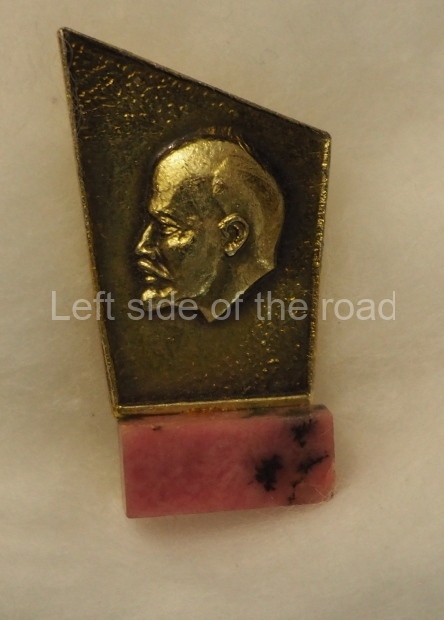

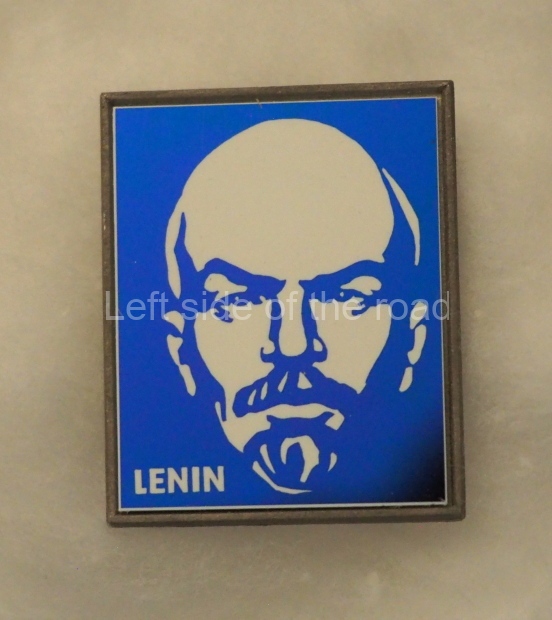

Whenever the mass production of these badges started – and for whatever reason – there may be many readers who haven’t had the opportunity to see examples of these images of VI Lenin. Hence, the slide show below to rectify that omission.

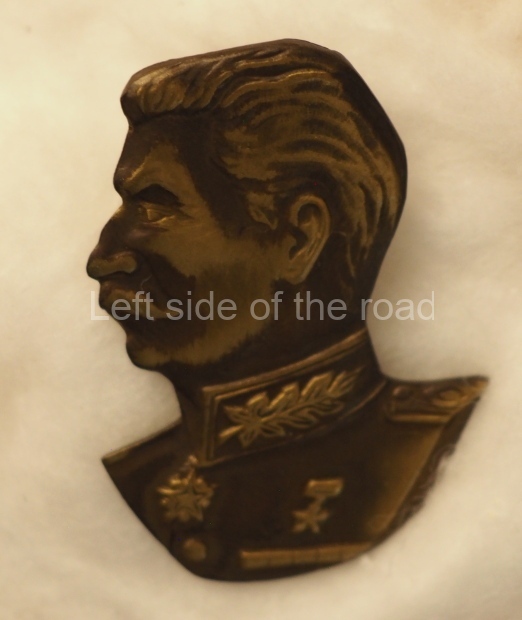

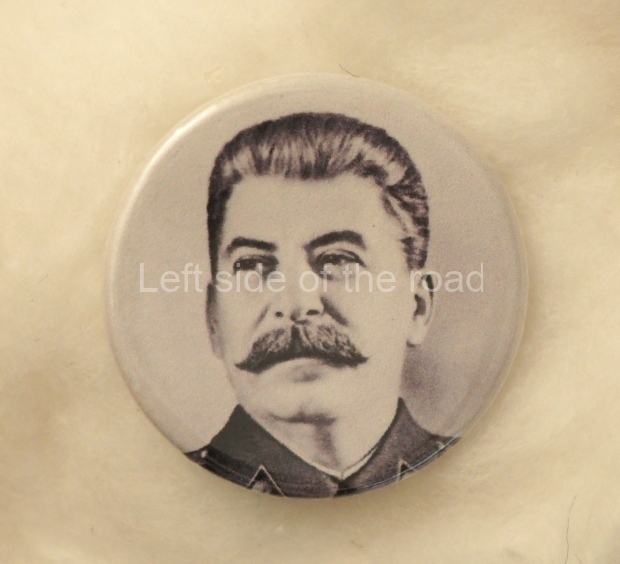

Also included are a few examples of badges with the image of JV Stalin. These have been produced in very recent years and, to the best of my knowledge, none were ever produced in the erstwhile Soviet Union.