More on the Maya

Tabasqueño – Campeche

Location

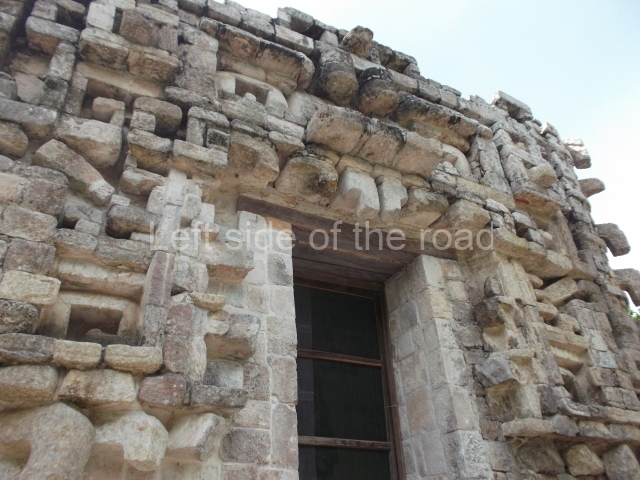

This site boasts one of the finest examples of an intact zoomorphic facade, that is, a doorway turned into the representation of a mythical monster. Tabasqueno is situated south of Hopelchen, in the north-eastern region of Campeche called Chenes. The name of the site dates from the last decade of the 19th century, when it was first reported and photographed by Teobert Maler. At the time, there was ranch near the ruins called El Tabasqueno, owned by a man from the state of Tabasco (hence, Tabasqueno = Tabascan). To reach the site, follow the road from Hopelchen to Dzibalchen, some 34 km, and then take the west turn off and drive on for another 2 km.

History of the explorations

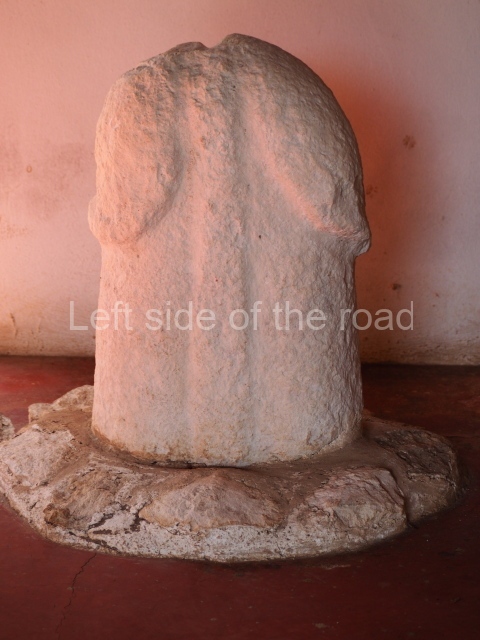

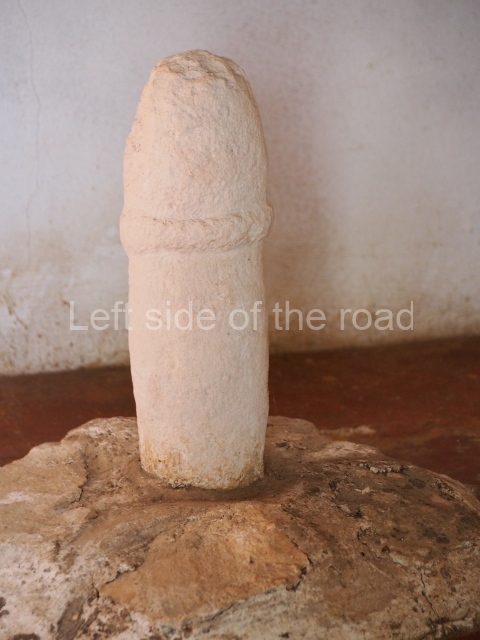

Due to the remoteness of the site, the archaeological ruins remained submerged in the rainforest. In 1936 the American archaeologist Harry Pollock conducted a survey of the region and published his findings in 1970. In 1956 Ricardo Robina undertook another survey of the main buildings at the site. Agustin Pena (INAH) carried out the first consolidation works on Building 1 or the Temple-Palace in the late 1970s. During the following decade, the architects Paul Gendrop (Autonomous University of Mexico) and George Andrews (University of Oregon) produced more detailed reports of the site, studied some of the buildings and published their findings. Renee Zapata (INAH) drew up a preliminary map of the settlement and Abel Morales (Autonomous University of Campeche) embarked on a study of the astronomical orientations of some of the buildings. Conservation works were led in 1992 by Antonio Benavides C. (INAH). In 1995 Building 1 was severely damaged by the hurricanes Opalo and Roxana, resulting in the collapse of most of the upper facade. The restoration works were recommenced in 2003 under the supervision of Ramon Carrasco (INAH). In 2009 Sara Novelo O. and Antonio Benavides C. conducted consolidation works and reported the discovery of four monoliths with reliefs corresponding to the Terminal Classic (AD 800-900). These iconographic elements add to the corpus of images from the Chenes region and link the site to several Mesoamerican regions.

Timeline and site description

The architecture and ceramics at Tabasqueno indicate that the site was mainly occupied between the 7th and 10th centuries AD (Late Classic). Its main buildings compose four monumental architectural groups distributed on the tops of hills that have either been levelled or modified. Chultunes were built on some of the platforms.

North group.

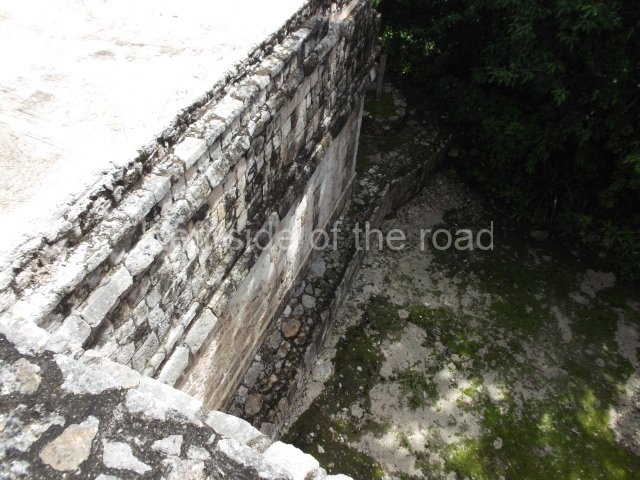

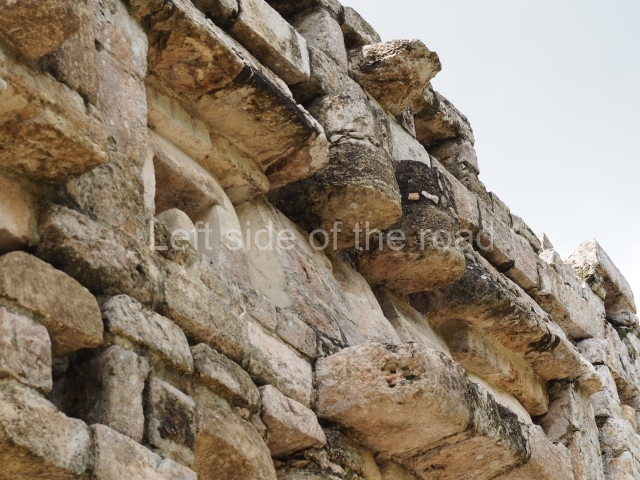

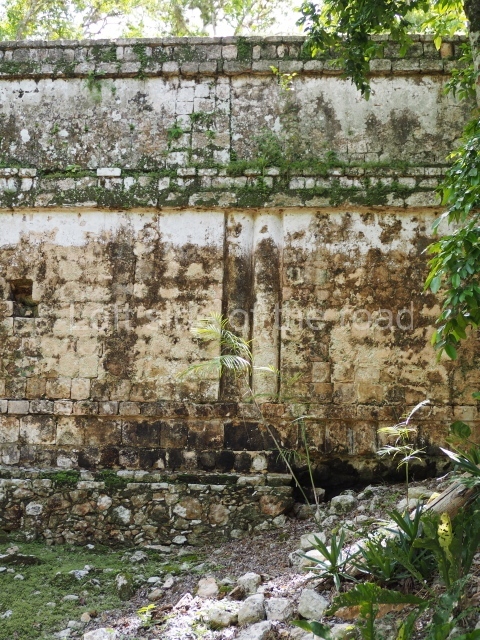

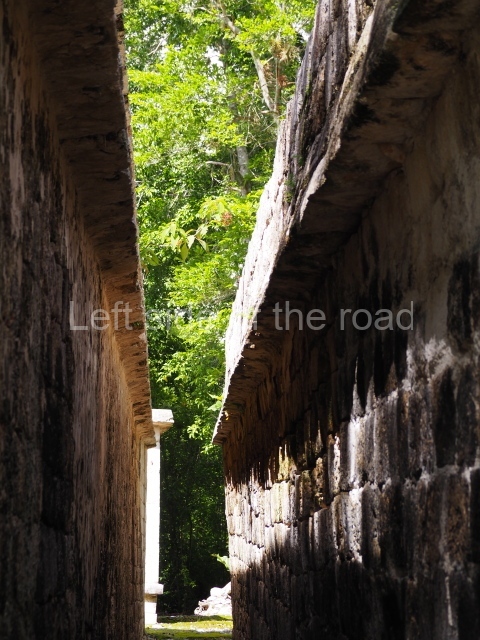

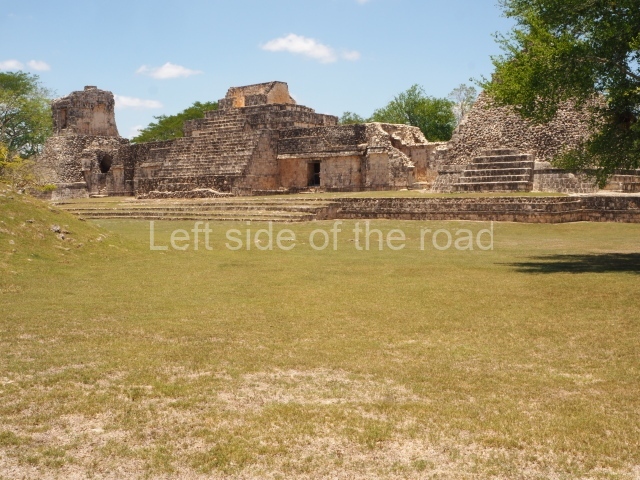

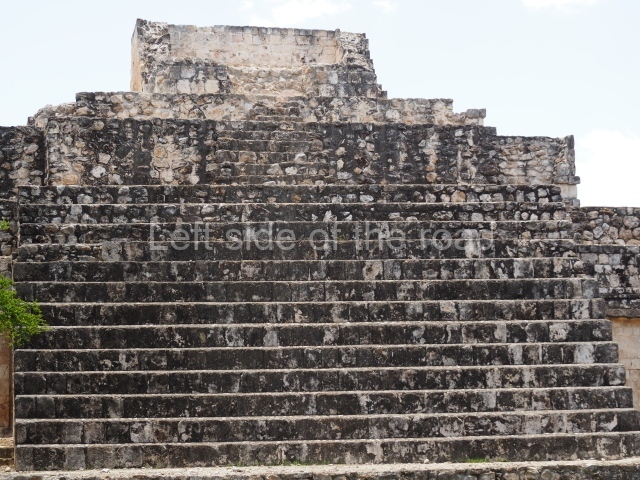

The first group comprises the remains of the Temple-Palace or Building 1, the best-known construction on the site due to its imposing zoomorphic facade. A two-storey construction, it seals the south side of a plaza measuring 60 m (north-south) by 40 m (east-west). Eight rooms have been recorded on the ground floor, including two smaller ones in the stairway filling – an ingenious solution for saving material and creating more covered spaces. The generous proportions of the other six rooms suggest that they were used as elite residences. On the top floor it is still possible to see the room on the north side, the one on the south side having been lost prior to the discovery of the site. An impressive image of the powerful god Itzamna occupies the entire facade, whose monumentality is further increased by a perforated roof comb, part of which can still be seen. The giant mask, which stands over 5 m high, is flanked by stacks of long-nosed masks, which form the corners of the construction. A courtyard lies north of the Temple-Palace, bounded to the north by a construction that once contained 12 rooms, distributed in pairs and all south-facing. The west side of the courtyard had more rooms with corbel-vault ceilings, but these are on a lower level and face the west. Bounding the courtyard to the east is a large mound of rubble, the ruins of which suggest the existence of corbel-vault rooms.

Tower group.

The second group is situated some 60 m south-west of the Temple-Palace. It appears to have served astronomical purposes and at the centre stands a square-plan tower (1.5 m x 1.5 m), just over 4.5 m in height. It has simple moulding around the upper section and stone tenons at the top that may well have supported stucco figures. Several other towers similar to the one at Tabasqueno have been found in the Chenes region, most notably at Nocuchich and Chanchen, although these still have roof combs. The comparison of the three constructions led George Andrews to suggest that they were stylised representations of temple buildings with high roof combs. Meanwhile, Abel Morales of the Autonomous University of Campeche has suggested that the shadows cast by the tower may have indicated important dates in pre-Hispanic ceremonies associated with the equinoxes and solstices.

South group.

The third group is situated just south of the previous group on an artificial platform with several mounds of rubble in the northern section. Some of these stand over 4 m high and the veneer stones suggest that the buildings now lost contained rooms with corbel-vault ceilings. There are fragments of lintels and an altar, and although most of these pieces had suffered severe erosion when they were discovered their presence nevertheless may well indicate that there are more and better texts and images on the site.

West group.

The fourth group is situated approximately 80 m to the west of the first group. The rubble mounds suggest an architecture requiring a great deal of labour and attention to detail. There are low platforms and lines of pebbles around the architectural group, which indicate the former existence of dwellings made of perishable materials for inhabitants with a lower social and economic status.

Importance and relations

Judging from the architectural, epigraphic and iconographic evidence, Tabasqueno was an important city, despite the nearby location – 5 km to the north – of Pakchen, which also has impressive, formerly vaulted constructions. The monumental ruins at Hochob, 10 km to the south, are less impressive. Chunbec and Dzibiltun lie to the north-east and north-west of Tabasqueno. The future will hopefully provide us with greater knowledge about the western section of the Chenes region.

From: ‘The Maya: an architectural and landscape guide’, produced jointly by the Junta de Andulacia and the Universidad Autonoma de Mexico, 2010, pp 315-316

How to get there:

From Hopelchen. Take the Iturbide bound bus from Hopechen and get off at the approach road to the site at around km34 – about 4 km after the village of Pakchen. Then it’s a 2km walk to the site. There is also a combi that goes to Ukum which leaves Hopelchen from outside the Oxxo convenience store, on the south side of the main church.

GPS:

19d 30’ N

89d 47’ W

Entrance:

Free