More on the Maya

Aké – Yucatan

Location

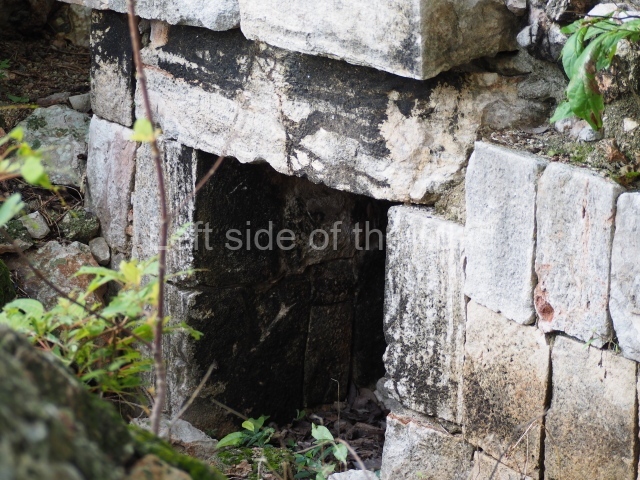

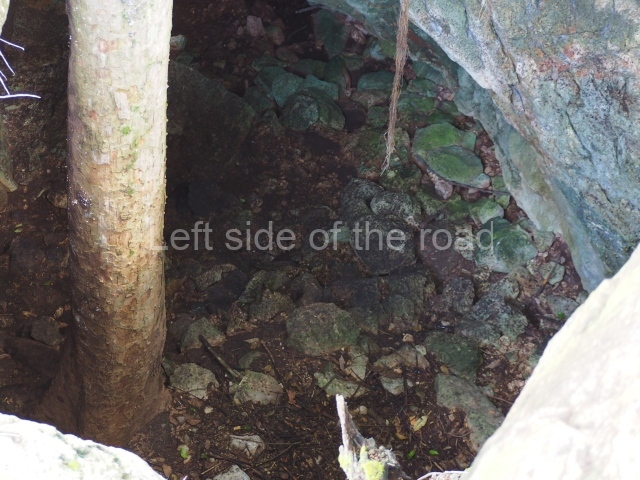

This site is situated in the north-west of the state of Yucatan, 33 km from the city of Merida by federal road 80, which leads to Tixkokob and Ekmul. Aké is used as the toponym, but the word ak’ on its own means ‘liana’. The area where the archaeological site is located is characterised by the same type of terrain and climate as Merida. The natural wells (cenotes) and depressions (aguadas) are the principal guarantees for the supply of water in northern Yucatan. There are several cenotes in Aké, which in pre-Hispanic times must have provided the main sources of water, as well as two possible aguadas. Due to years of burning and planting henequen (a type of agave cactus used to make sisal rope) in Aké, most of the present-day landscape is given over to low woodland and bushes (Tsitsilche, Sakkatsin, Subi’n, Tsiuche, Yaxmuk, Zacate, etc.).

History of the explorations

Aké was first reported many years ago by travellers and Mayanists such as Desire Charnay, Teoberto Maler and Lawrence Roys and Edwin M. Shook, who drew up the first map of the core area of the site. More recently, the Atlas Arqueologico del Estado de Yucatan classified Aké as a second-class site. In 1979, Ruben Maldonado Cardenas and the INAH launched the Aké Project and conducted several field campaigns, leading among other things to the restoration of the Temple of the Columns, the first map and the excavation of stratigraphic wells in various structures in the residential area. In 2003, a new phase of research and restoration commenced at Aké aimed at confirming its complexity, timeline and regional importance. Maps were drawn up and excavations undertaken to establish the occupational timeline and gain a clearer idea of the form and function of its buildings and spaces. The project continues to this day led by Beatriz Quintal Suaste.

Pre-Hispanic history

The surface ceramic material recovered and the excavation of stratigraphic wells confirm an occupation stretching from the Late Preclassic (300 BC-AD 300) to the Postclassic (AD 1300-1450). The present-day population is principally the result of the boom in the cultivation of henequen. The longest period of occupation demonstrates significant growth: Aké must have started out as a village that subsequently expanded and gained in importance, finally becoming a city-state with control over the immediate vicinity.

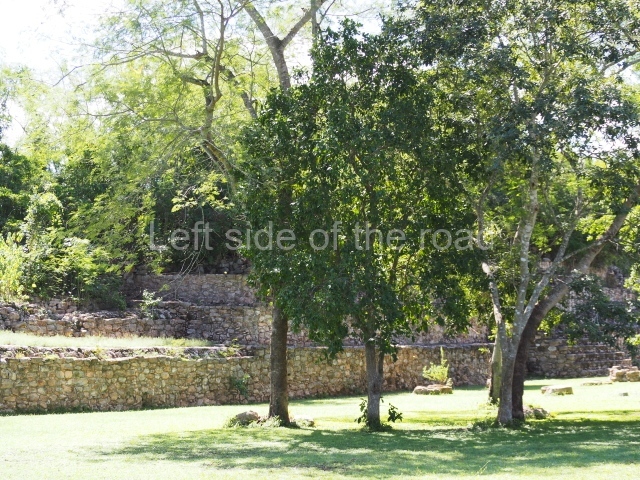

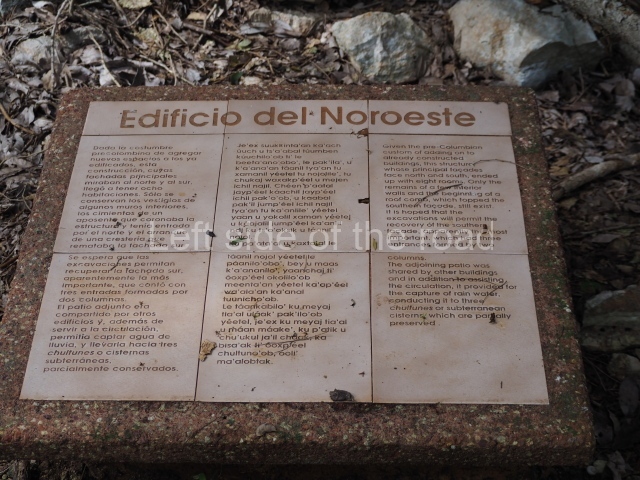

Site description

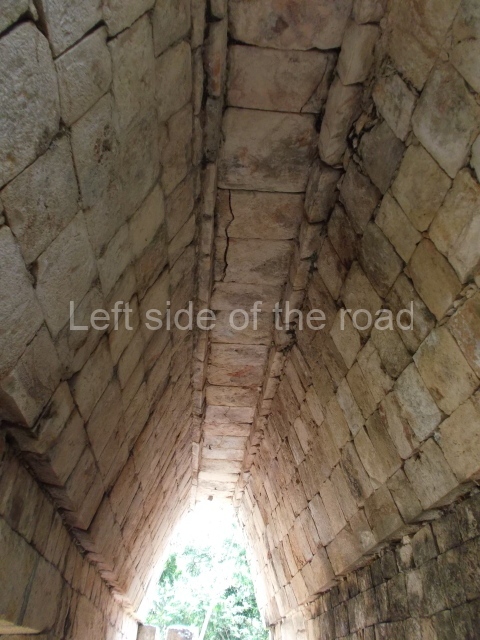

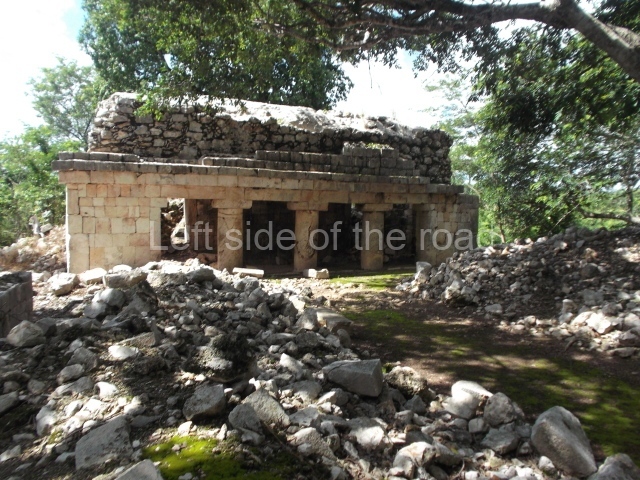

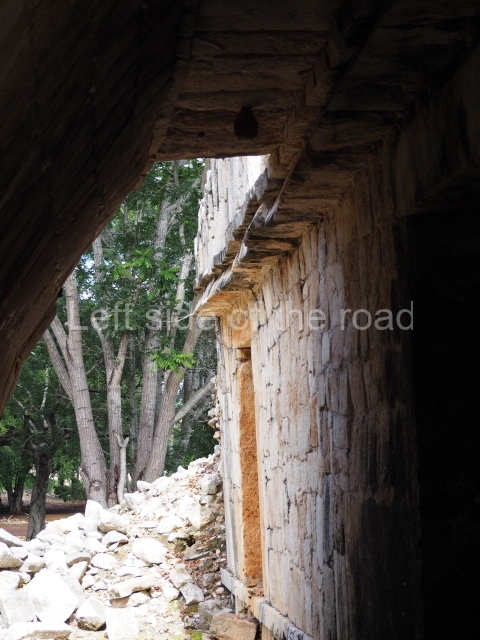

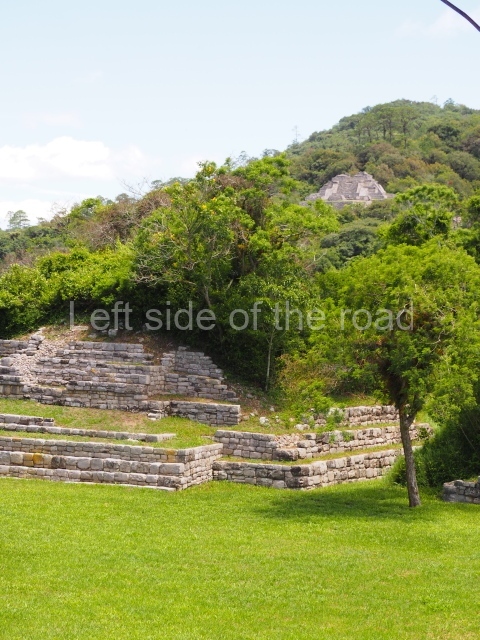

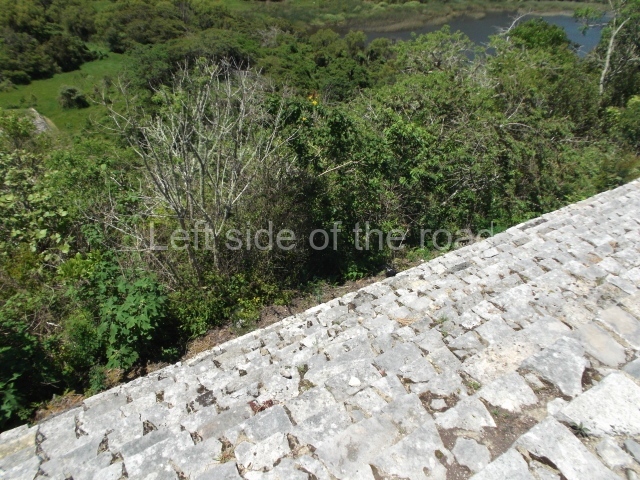

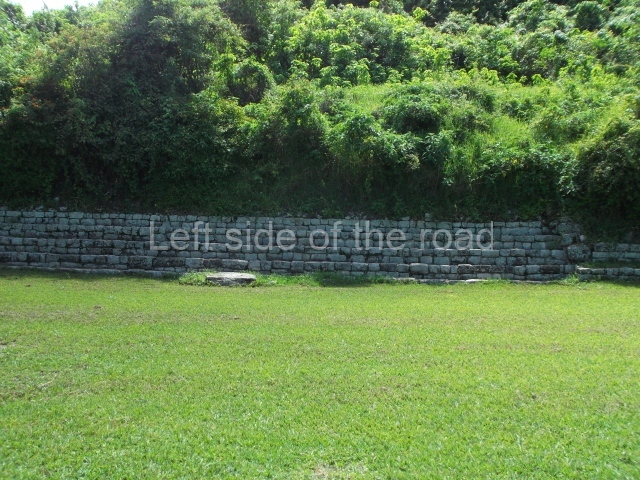

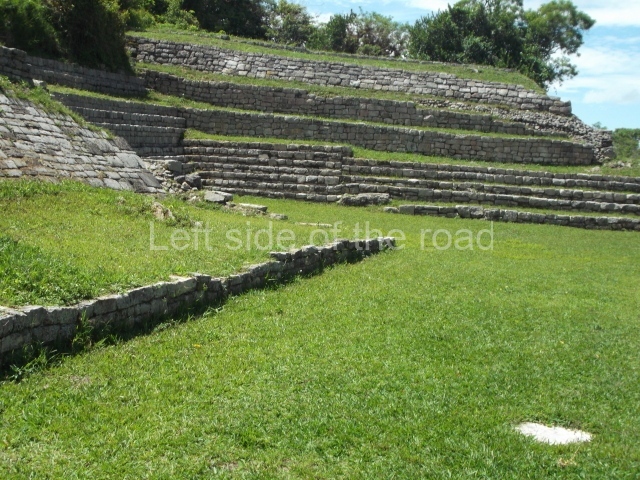

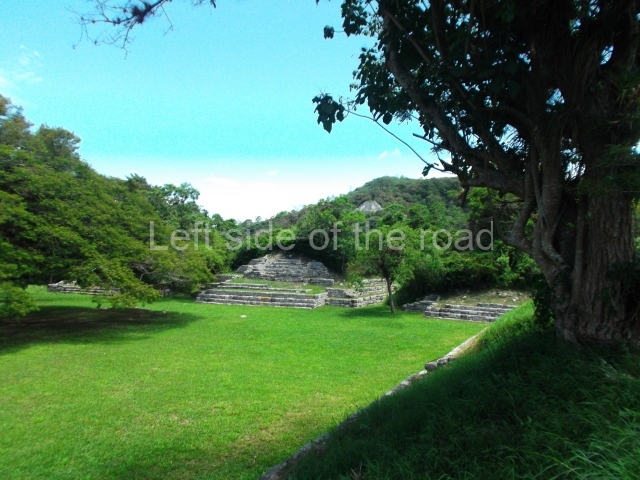

The archaeological site consists of two separate sections delimited by two walls. One wall encircles the core area, where the monumental structures are situated, while the other encloses most of the residential area. Situated at the centre of the settlement is a rectangular plaza; Structure 1 or the Temple of the Columns defines the north side, structures 13 and 19 the east side, Structure 7 the south side, and structures 6 and 2 the west side. The plaza covers an approximate area of 25,000 sq m and the residential zone an approximate area of 4 sq km.

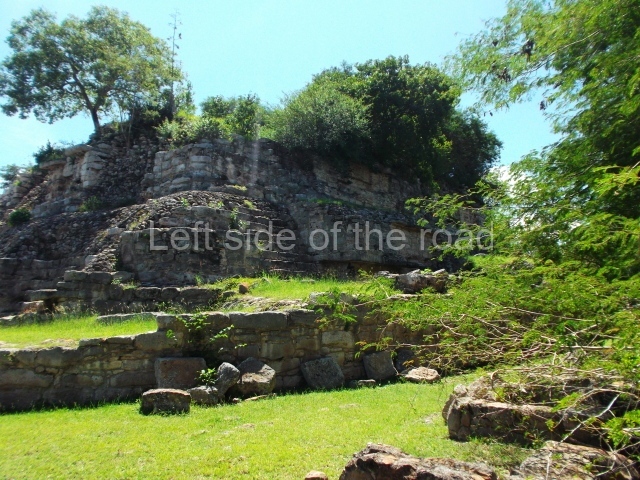

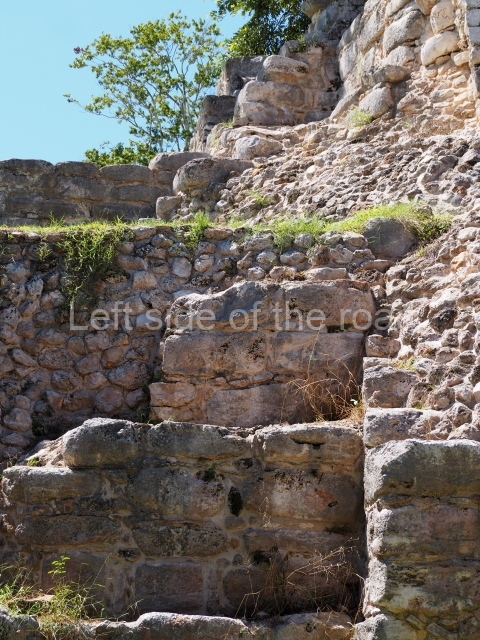

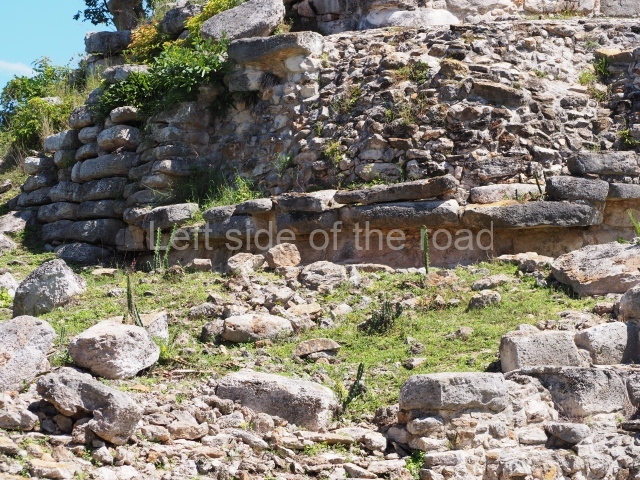

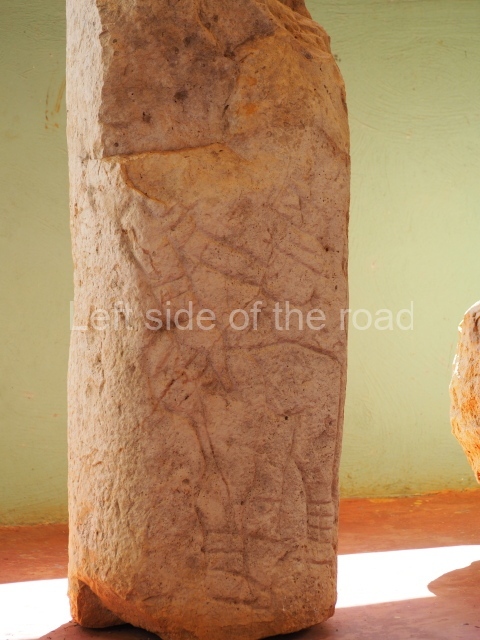

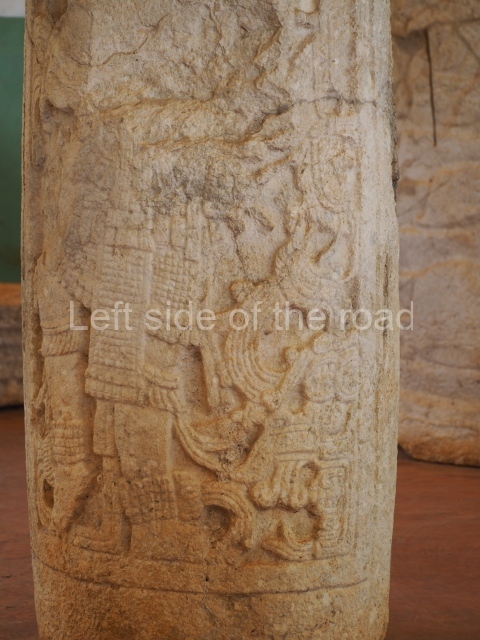

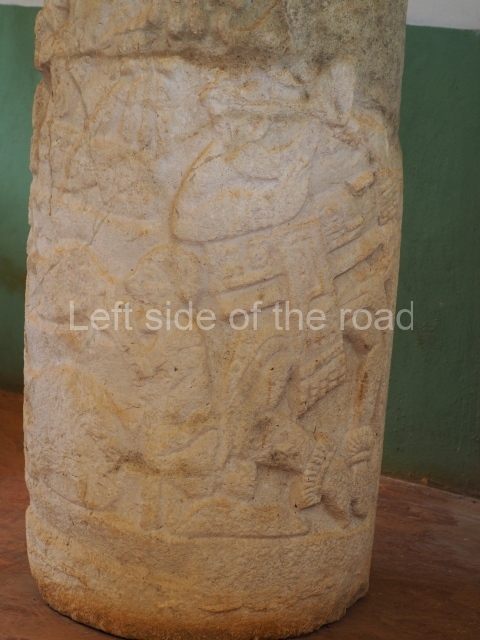

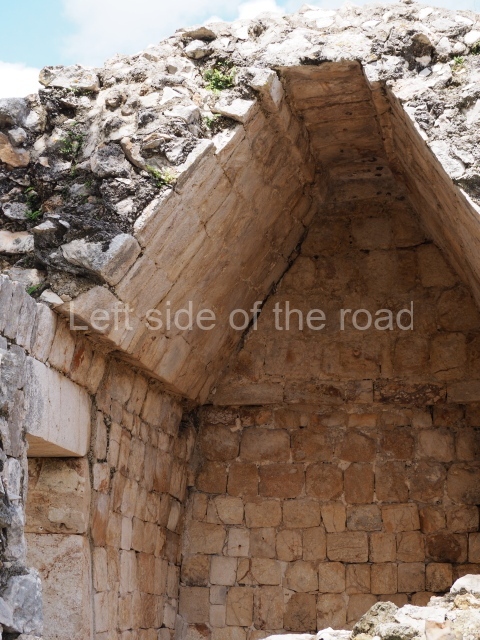

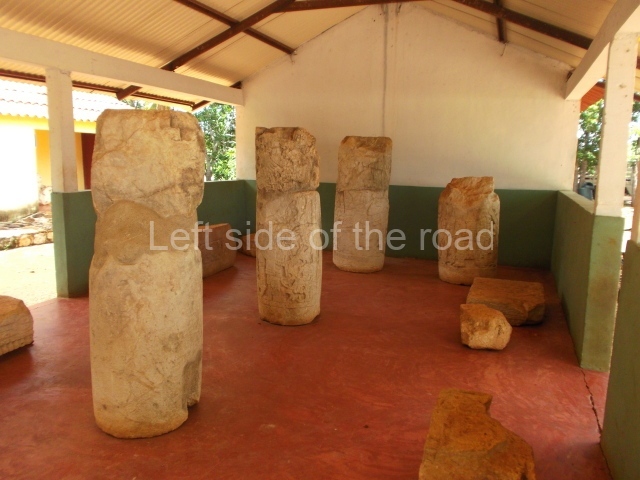

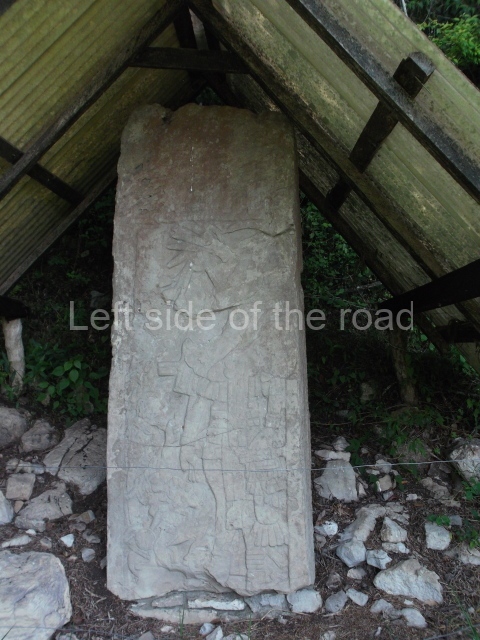

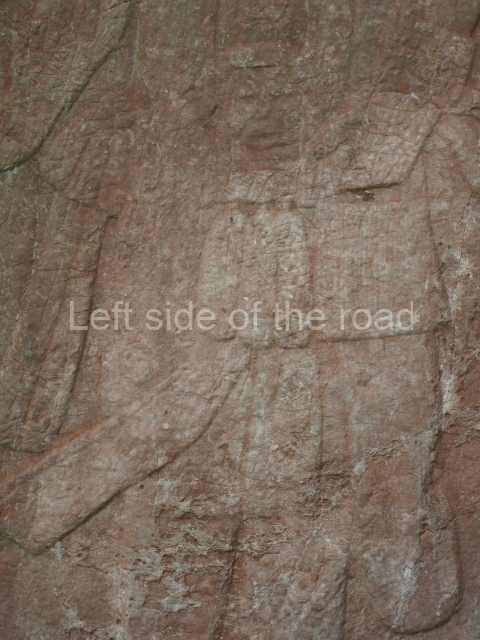

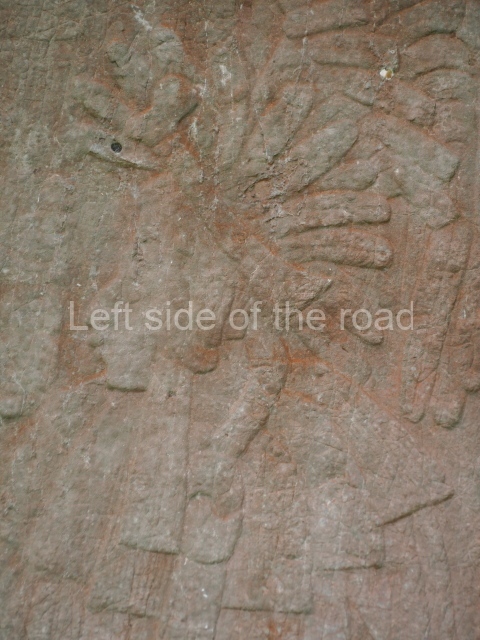

Structure 1 or Temple of the columns.

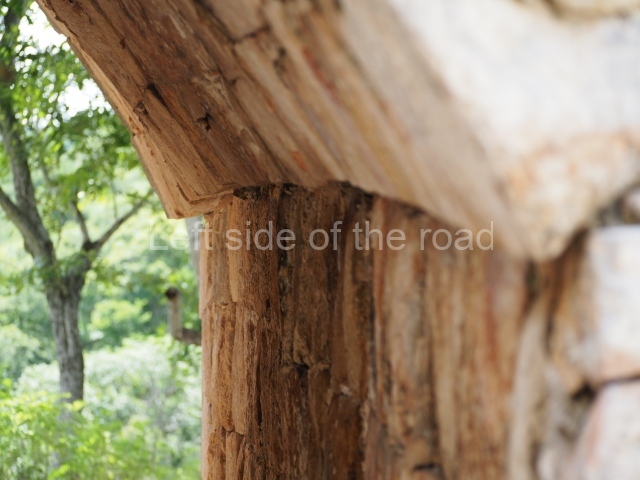

This is a vast construction measuring approximately 103 m in length by 32 m in width at the narrowest section and 36 m at the widest. It is fronted by a monumental stairway made of large blocks of limestone. On the platform at the top of the stairway, which measures nearly 67 m in length and 14.20 m in width, are three rows of large columns, making a grand total of 35. These pre-Hispanic structures probably supported one of the largest roofs in Mesoamerica. Visible between the columns is a small promontory on which stands part of the lower section of the walls of what must have been a room added much later.

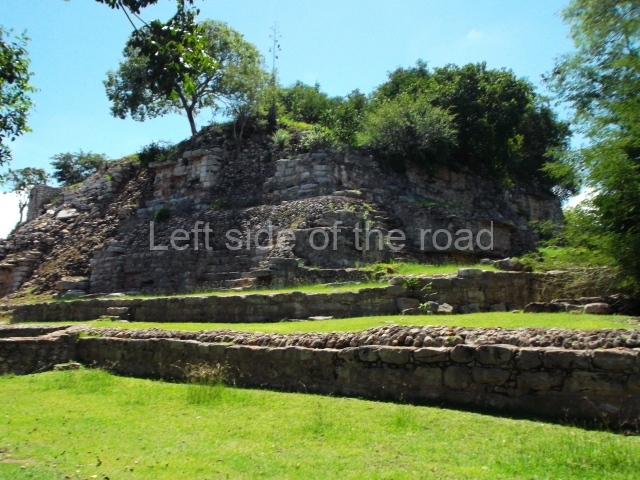

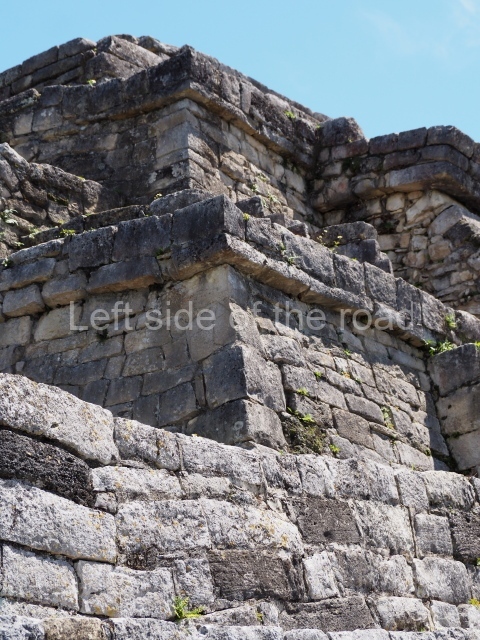

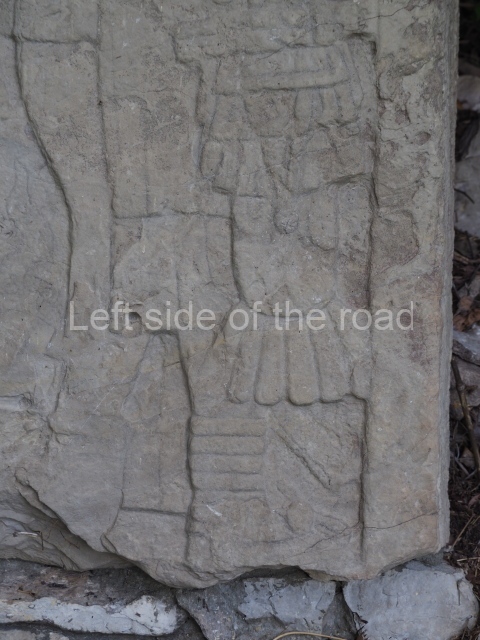

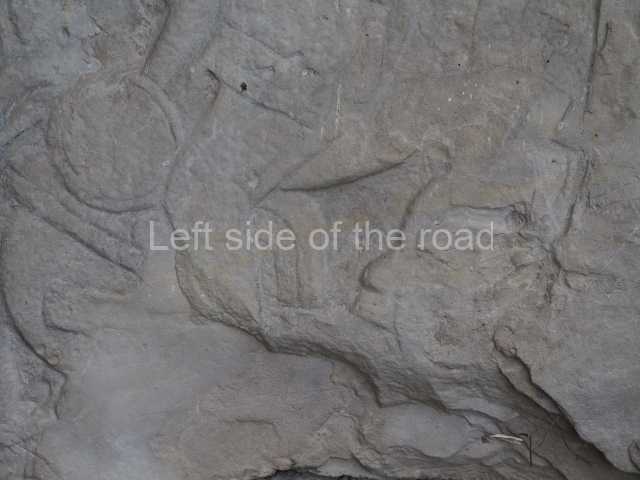

Structure 2

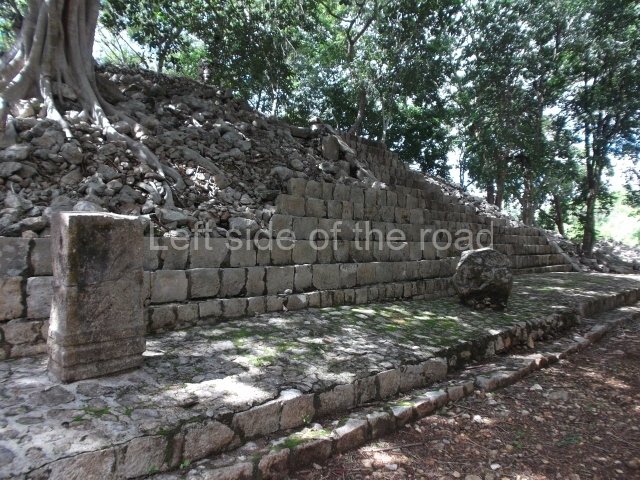

This occupies the west end of the great plaza and adopts an apse-shaped plan measuring 45 m along the sides and standing approximately 15 m high. It would appear to have had four entrances, one on each side. The excavations revealed two construction phases: the first, corresponding to the Early Classic, is associated with the Megalithic style; the second, which covered the first phase and denotes the use of smaller blocks of stone, corresponds to the Proto-Puuc style developed at Oxkintok. The platforms are decorated with an inset talud and tablero (slope and panel) and apron moulding, like those reported at Oxkintok, Dzibilchaltun and El Mirador in Yucatan (Varela and Quintal).

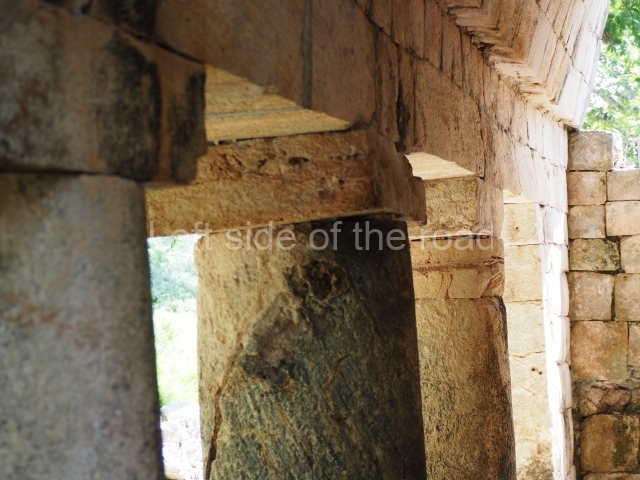

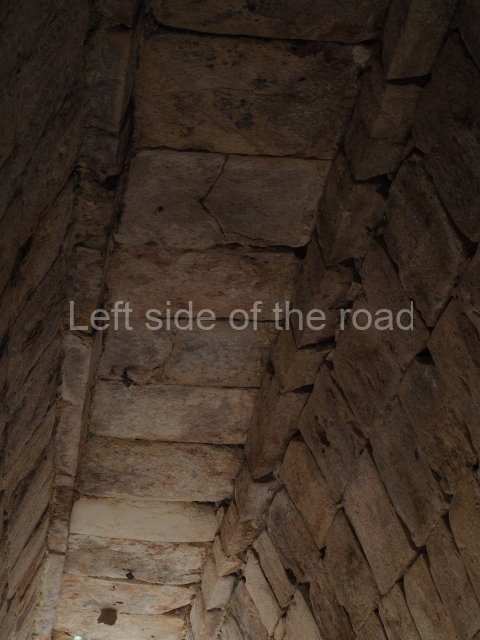

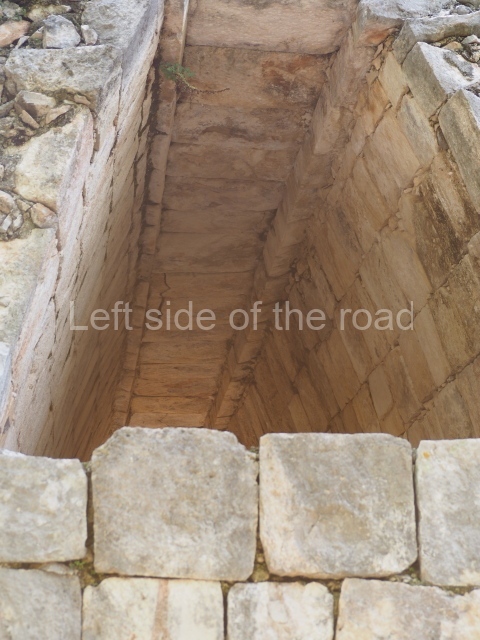

Structure 3

This is situated west of Structure 2 and consists of a building erected on a sub-structure; it measures approximately 43×29 m and stands 6 m high. The upper structure is subdivided into a row of five rooms from east to west, with a single room on the south side and another on the north side. The plan is clearly defined by the existence of low walls, some of which are still standing and rise to a height of nearly 2 m. The column entrances were made of square blocks of stone placed one on top of the other, exactly like the technique used for the columns in Structure 1. The room on the north side had a triple entrance and the one on the south side a quintuple entrance. In both cases the space between columns is 4 m.

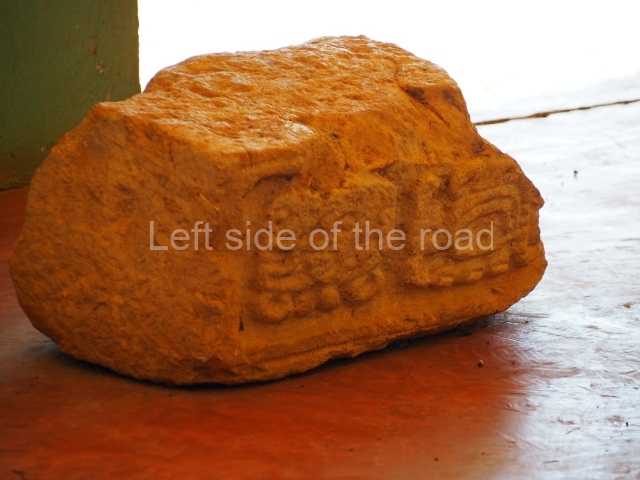

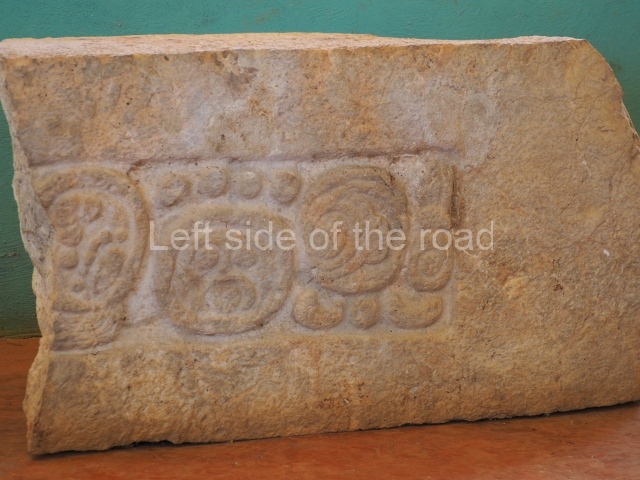

Ceramics

The preliminary analysis of the ceramic material recovered confirms an occupation stretching from the Late Preclassic to the Postclassic. The most representative ceramic groups include the Ucu, Saban and Sierra of the Chicanel Horizon; the Xanaba, Dos Arroyos and Chuburna of the Cochuah Horizon; the Katil, Conkal, Dzitya, Arena, Chum, Muna, Ticul and Teabo of the Cehpech Horizon; the Sisal Unslipped group of the Sotuta Horizon; and the Mayapan group of the Tases Horizon. The analysis has revealed a numerical predominance of the groups corresponding to the Cehpech Horizon.

Beatriz Quintal Suaste

From: ‘The Maya: an architectural and landscape guide’, produced jointly by the Junta de Andulacia and the Universidad Autonoma de Mexico, 2010, pp 390-391.

How to get there:

From Merida. There are colectivos that regularly leave from Calle 63, entre 52 y 50, going to Tixkokob. They take about 45 minutes and cost M$20. From there you might be lucky to pick up public transport but it will unlikely be at convenient times. Your best bet is to negotiate with a tuk-tuk driver to take you to the archaeological site, wait and then bring you back.

GPS:

20d 57’20” N

89d 13’10”

Entrance:

M$70