Arenas de Barcelona – Placa de Espanya

Arenas de Barcelona, the bull ring right next to one of Barcelona’s busiest roundabouts at the Plaça de Espanya, had been closed for years. Bull fighting has its supporters throughout the Iberian Peninsular but it never had such a fan base in Catalonia as it did, and still has, in the likes of Andalusia and Extremadura. Come the 1970s and it’s owners considered it wasn’t a viable concern. For bull fighting fans that wasn’t such a total disaster as there was another large ring only a few kilometres east along the Gran Via de Les Corts Catalanes at Monumental.

In some ways that was a pity. The building was completed in and opened as a fully functioning bull ring in 1900. For more than 70 years it provided those with a thirst for blood the opportunity to see a fine young animal fight a losing battle for its life. No doubt Hemingway would have been one of the paying or, perhaps because of his fame, not paying guests. In 1977 the place closed for good.

From the outside it’s a beautiful structure. Catalonia was the first region of what became Spain to have defeated the Moors so there are few examples of Moorish, or the later Mudejar architecture, in Barcelona. The architect for the original building was the Modernist August Font i Carreras, not one of the more radical of the architects of the time, such as Gaudí (of Park Güell and Sagrada Familia fame) or Domenech i Montaner (designer of Hospital de La Santa Creu i Sant Pau and the Palau de la Música Orfeó Català), but one who looked to those architectural devices of the Moorish past that are common, even ubiquitous, in cities like Granada, Cordoba and Seville.

The exterior of the structure takes on the same geometric design as what is to take place inside, that is it is circular. I mention that because that’s fairly unusual for a bull ring, at least most of the ones I’ve seen in different parts of Spain. Most have square walls at entrances or where the bulls might be corralled before facing slaughter. This is the situation at the other Barcelona bull ring at Monumental. However, Font i Carreras opted to put all these services inside the shell and so it makes for a very pleasing sight for the eyes.

The Arabic arches over the doors and windows are all around the circular building, following the normal pattern of getting smaller as they are reproduced higher up the structure. The crenellations over the entrances, the alternating stripes of brown/ocre and white, the use of blue and white tiles will not surprise anyone who had visited the south-western part of Spain.

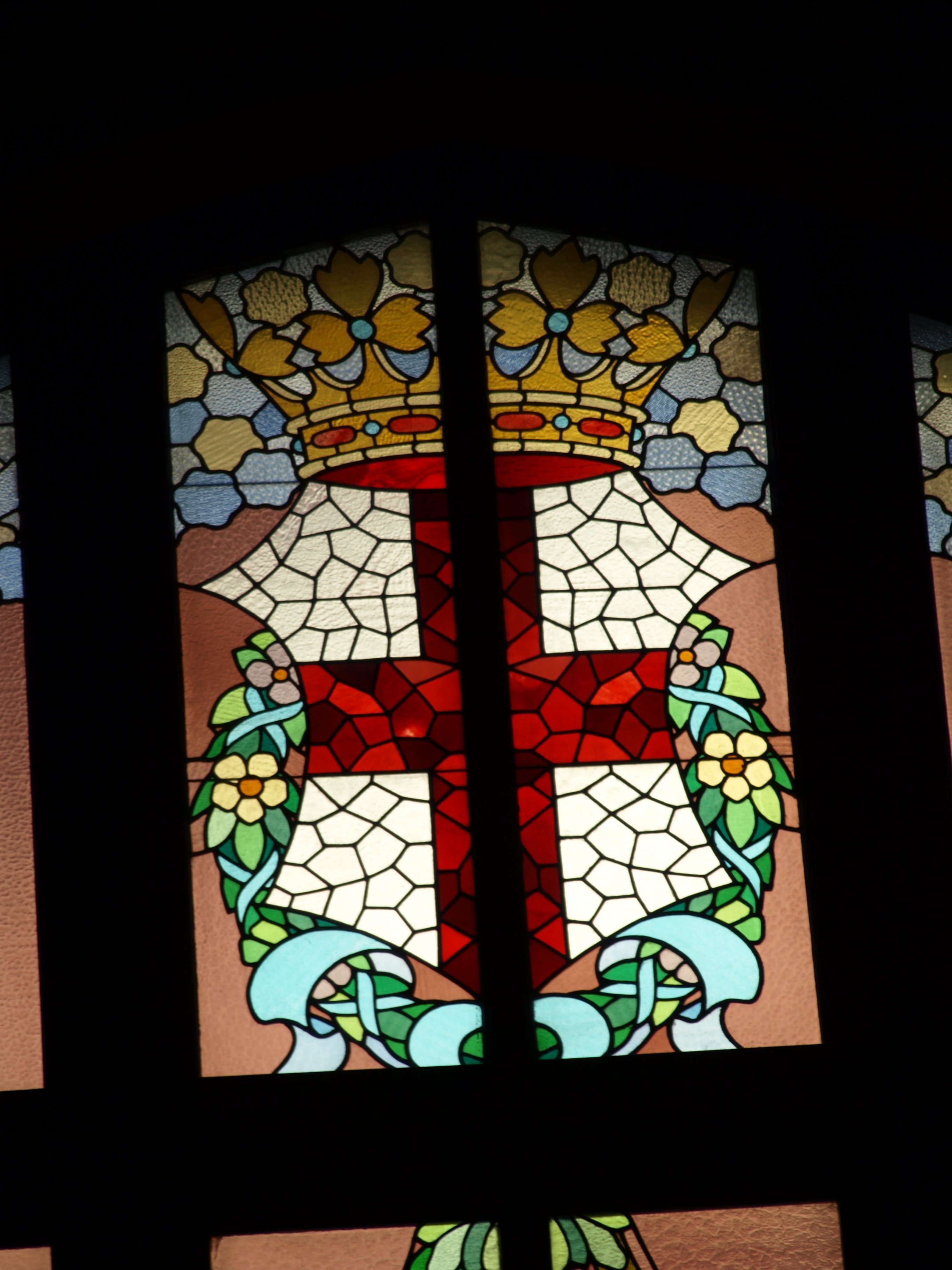

Over the principal entrances, together with an homage to the Spanish crown there’s the red and orange stripes representing Catalonia. Although I haven’t seen pictures of it I would have assumed that these would have been blanked out during the Fascist period under Franco. This happened in those iconic buildings of Catalan Modernism, such as the Palau de Musica, so I see no reason to believe that they would have disappeared on this bull ring.

The Arenas de Barcelona was just left to rot after the last bull fight in 1977 and must have been a bit of an embarrassment for the City Council and Regional Government located as it is at one of the most important traffic junctions in the western part of the city. Not only that the Plaça de Espanya is the entry point to the city’s exhibition area and the highest point in the city, Montjuic. It was there the 1992 Olympics were staged, with the main stadium, swimming/diving pool and indoor sports hall all being found there. It is also the location of the Joan Miro Foundation.

In 2000 the contract for the project was given to Rogers Stirk Harbour + Partners (that’s Richard Rogers of Lloyd’s bank in the City of London – among many others – fame). Fortunately it was decided to keep the original structure, or at least the façade, but create within the space originally occupied by the bull ring a new shopping, leisure and entertainment complex. It opened in March 2011.

I knew what the plan had been but it was only last month I was able to see for myself. So it was with a certain level of apprehension that I approached the structure on a sunny day in late February – shopping is not really my thing.

First impressions were good. The exterior was as I remembered it but now cleaned up and repaired. The huge roof that appeared like an unturned saucer looked strange from street level and the lift shaft just to the left of the main entrance looked out of place.

If you visit the building don’t do as I do. I went immediately towards this lift shaft and as they were only charging €1 for the return trip I decided to go up on to the roof before entering the building itself. I just assumed that if there was a lift that was the only way to get on to the top of the building, it was only when I was walking around on the upper pavement that I realised that access was available from the inside.

Now a euro is not going to break most banks but I now wonder if it might not have been better to have first experienced the interior of the building from below. The lift only takes a few seconds and is only of interest to those who might have a penchant for glass lifts on the outside of buildings – perhaps to be avoided by those who suffer from any level of vertigo.

However you get to the top it’s worth it in the end. You’re able to walk the full 360º, one side looking towards Montjuic and the Museu Nacional d’Art de Catalunya (the museum which houses one of the biggest collections of Romanesque murals in the world as well as artefacts from late 18th and early 19th century Modernism), together with the steps that go on both sides of the fountains where there are sound and light shows on occasions, especially later in the year.

A walk of 180º from the lift and you can look down on to the small Parc Joan Miro, with its large bowling pin-like sculpture or up to the hills to the north, towards Tibidabo, where the silhouette of the Modernist Church of the Sacred Heart breaks the horizon. To the left of that is the spindly Torre de Collserola, the telecommunications tower, designed by another progressive British architect (or at least his partnership) and contemporary of Rogers, Norman Foster.

An attractive building on the outside it’s when you enter it that you see how vast has been the transformation from its original use. I came in from the top but would think you’d get a better impression of scale from entering at street level and then looking up.

What has been created is a huge engineering masterpiece that just uses the old structure created by Font i Carreras as a cloak to hide the intricacies of 21st engineering skills. There’s no way that the circular brick structure holds any of the weight that’s inside. This is carried by huge tubes, at the cardinal points of the compass, that hold up the five levels above the basement.

All the shops, cafés and the multiplex cinema are around the edges and there’s a circular space free of anything at all in the centre at street level. This is much smaller than the bull ring would have been but refers back to that past. This looks tiny from the very top of the building but is quite significant in size when you actually walk across it. It’s a pleasant surprise to me that nobody has appropriated this space and set up some kind of stall. This circle was clear of any obstruction when I visited but I’m sure would have been used as a performance space, for example, on occasions.

Linking the different levels are long escalators through the centre of the building which don’t call at all floors. Shorter escalators on two sides connect each floor so you could well find yourself walking the long way around to find what you want. I’m sure this was part of the plan – if you pass more shops you might be encouraged to buy – the sole reason for the existence of this 21st century structure. On one side there’s a lift with glass walls that goes from the very bottom to the very top of the building, all the workings being on show.

I thought it was a marvellous piece of engineering work in action and found myself going up and down escalators and lifts just for the fun of it – taking me back to the days of my childhood when we used to play on the first escalators to have arrived in one of the department stores in Plymouth.

I needed a reason to be there as there was nothing on sale – and everything was in a sale – that held any interest for me. All the shops were from a national or an international chain of some kind, really the only companies that could afford to be based in such a centre where more people shop with their eyes than their credit cards. One level was devoted to a multiplex cinema but even that’s no attraction as the overwhelming majority of cinemas in Spain/Catalonia show films which are dubbed and, as is the case in many countries, even ‘national’ films are confined to art house cinemas.

The whole of the basement level is devoted to a series of fast food outlets but then again mainly from chains or franchises. This increasing presence and dominance of such stores and outlets is something that is starting to take a greater hold in the peninsular. Going back 20 years or so there were few names that you would have recognised in the Barcelona shopping streets as most were one-off businesses. As the years go by they fall by the wayside as the bigger players chip away at the customers and soon walking down a Barcelona shopping street will be just like anywhere in Britain where the same names are above the doors whether you are in Brighton or Aberdeen. This has already happened with accommodation where the basic Pensiones are fast becoming a thing of the past.

Even if you’re like me and shopping provides as much joy as sticking a sharp sick in your eye the Arenas de Barcelona is definitely worth a look in if you are at this part of town for the exhibition centre, the Museu Nacional d’Art de Catalunya or on the way up to Montjuic.

Practical Information:

Getting there: The quickest way is on the Metro, Line 1 – the red one and getting off at Plaça de Espanya, though many buses also pass through this junction on the way to Sants Railway station.