Chichén Itzá

Location

One of the last great Maya cities, Chichén Itzá is situated 120 km east of the city of Merida, in the central northern area of the Yucatan Peninsula. The main entrance to the archaeological site is on the east side of Piste, near km 112 on national road 180, and a secondary entrance on the west side near one of the hotels built during a period of little control in the area. It comprises a large portion of the core area of the ancient city. The remainder of the secondary groups, the causeway network and several minor centres are situated within a protected area, which also has World Heritage status, and nowadays construction and modification of the environment are illegal, as is any impact on the various archaeological ruins, however insignificant they might seem.

The old karst plain in this region was originally covered by semi-evergreen seasonal forest rich in breadnut, jabin, chaca, yaxnik, cedar and other tree species that formed a medium-high rainforest with notable differences between the dry season (November-May) and the rainy season (June-October). There is often a brief interruption in the rain at the end of July and August, but it cannot be relied upon. The strong hurricanes that sweep the Caribbean and the Yucatan Peninsula in the rainy season provide an additional, high-risk factor of discontinuity. Chichén Itzá has access to underground water thanks to several cenotes, sinkholes and caves that penetrate the region’s water table at a depth of between 22 and 25 m. The name Chichén Itzá is a reference to one of these cenotes and means ‘the mouth or entrance of the Itzá well’. There is no surface water.

History of the explorations

Chichén Itzá reached its peak during the Terminal Classic and Early Post-classic, forming a long period of transition and growth rather than a period of separation between two very different or even conflicting cultural phenomena. It began to grow and gain importance towards the end of the Late Classic and then lost importance in the region in the mid-Post-classic, although the region was never abandoned completely – it was still an important site of pilgrimage and sacrifices when the Spaniards reached Yucatan. In the traditions it was referred to as the historical capital of the Itza people, renowned warriors during the centuries prior to the Conquest. The first descriptions of the ruins can be found in the Relacion de las cosas de Yucatan by Bishop Diego de Landa, written less than 30 years after the foundation of Merida. During the colonial period, it became a livestock ranch, but with the growing interest in antiques at the beginning of the 19th century it was one of the first Maya sites shown by local antique dealers.

Pre-Hispanic history

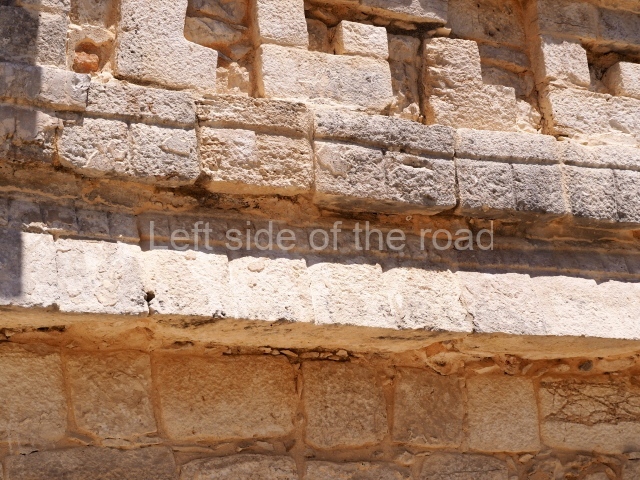

The complete historical record of Chichén Itzá is still missing a great deal of information and the issue is further complicated by the numerous contradictions in the written sources. According to the ceramic evidence, there were one or several smaller sites or villages between the Middle Preclassic and Early Classic (500 BC to around AD 600). There is a larger accumulation of ceramic artefacts and decorated stone blocks from the Late Classic, which were re-used in the constructions, platforms and plazas of the expansion phase following the first prosperous phase. There are obvious influences from the Late Puuc style, although this does not mean that Chichén Itzá belongs entirely to this cultural formation.

Nearly all the long, detailed inscriptions in the Maya glyphic script date from a short period, although they do not display the same calligraphic quality as those of the earlier temples in the central Maya area or, to a certain extent, those of the nearby Ek’ Balam and Coba. The content of the inscriptions is also different in that these are no longer devoted exclusively to the glorification of a specific governor or dynasty, which has given rise to the hypothesis that the system of government at Chichén Itzá was different from that of earlier Maya states, being based on consensus government rather than monarchic government. The only historical figure who, along with his immediate family, seems to have enjoyed a certain power is a ‘great captain’ Kakupacal (Shield of Fire); several other names appear but tend to refer to gods.

The vast majority of the buildings at Chichén Itzá correspond to the so-called Modified Florescent style, an architecture that combines the Maya traditions of the northern Yucatan plain and the centre of the peninsula, the aforementioned Puuc style and concepts, layouts and images from other parts of Mesoamerica, especially the Gulf coast and the central and even western plateau. This architecture incorporated new elements and created a unique style for Chichén Itzá, which has been described as ‘Mexican’ or even ‘Toltec’ due to its similarities with the distant Tula de Hidalgo, the capital of the legendary Toltecs. Nowadays, hardly anyone believes that Chichén Itzá was conquered by vast numbers of foreign people, but the mechanisms that explain many of its surprising relations are still the subject of increasingly sophisticated research. We still do not know the directions followed by the various elements they had in common. This composite culture, which nevertheless had a very strong Maya base from the outset, may have emerged during the first half of the 9th century and been subject to the Puuc influence until the end of that century, thereafter continuing as a distinct culture during the first half of the Post-classic, when Chichén Itzá reached its peak. Most of the important constructions date from this period. The principal ceramics are a variant of the large Slate ceramics. Worship of the Sacred Cenote also began at this point, with rich offerings and even human sacrifices.

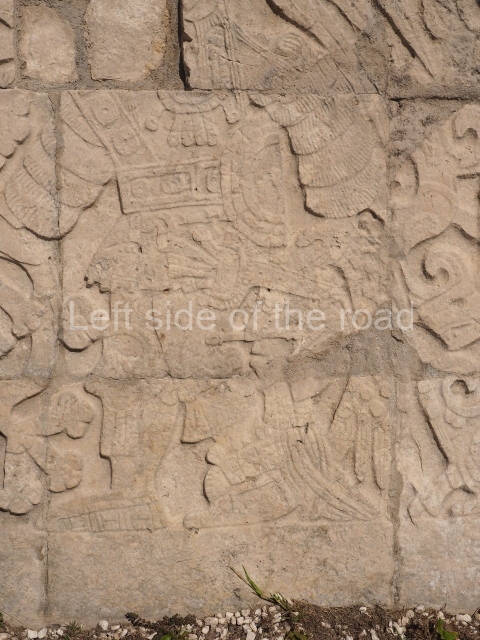

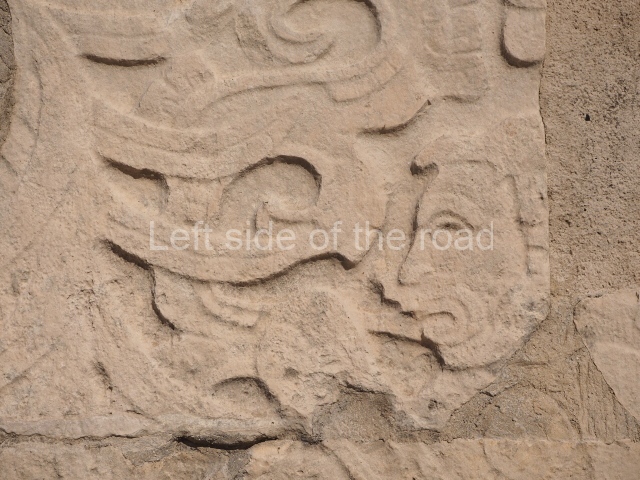

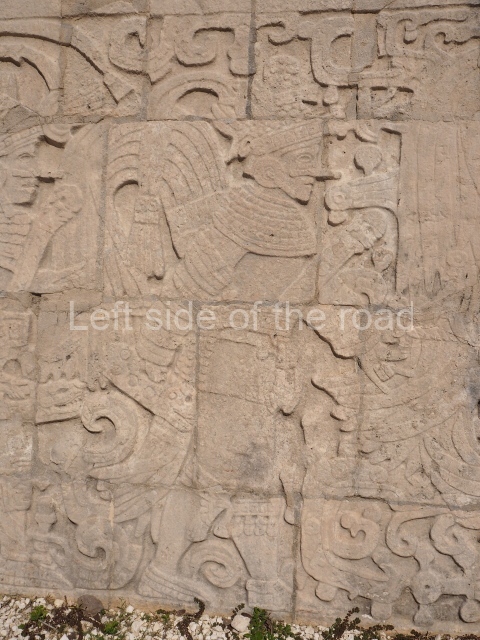

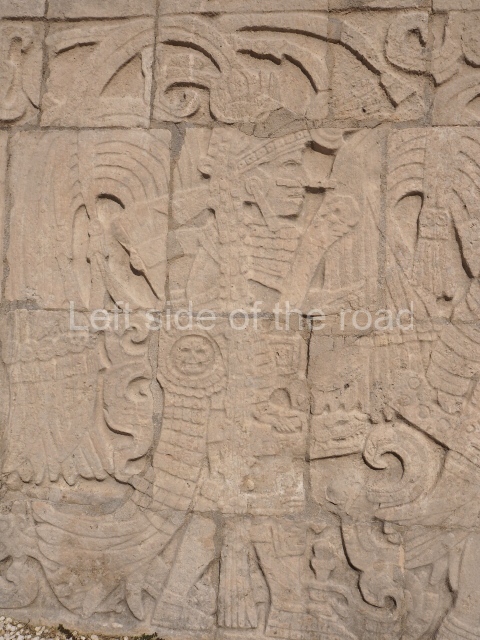

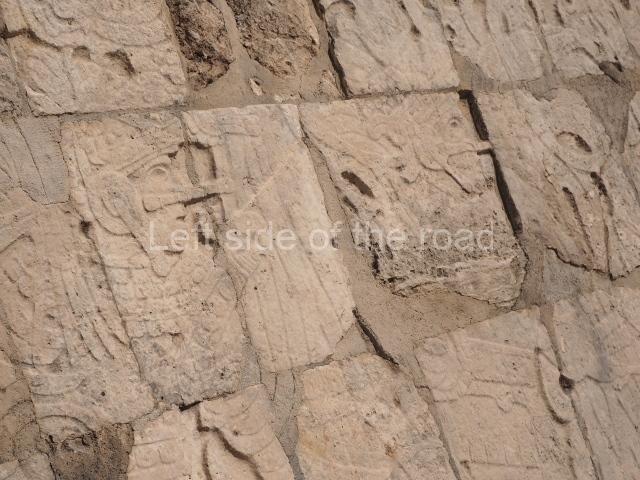

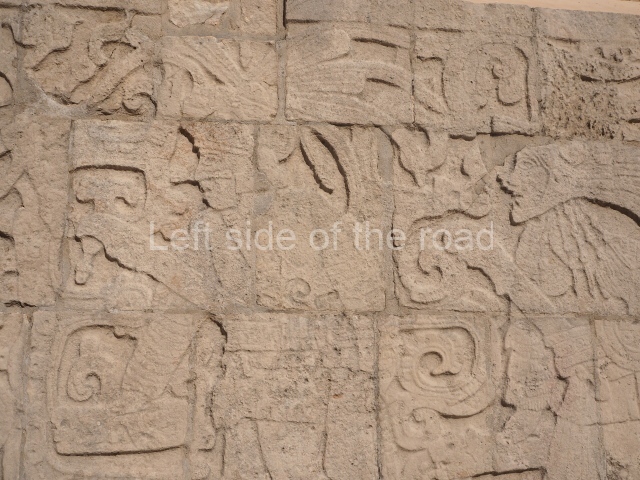

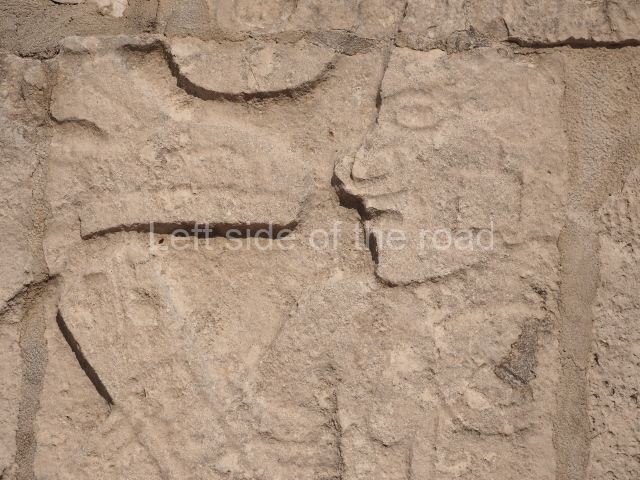

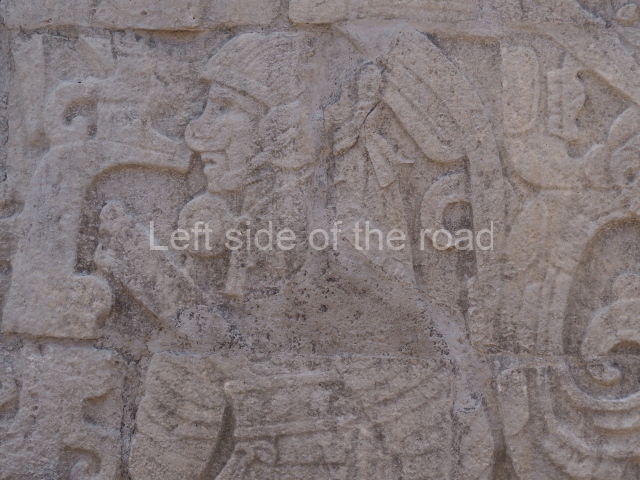

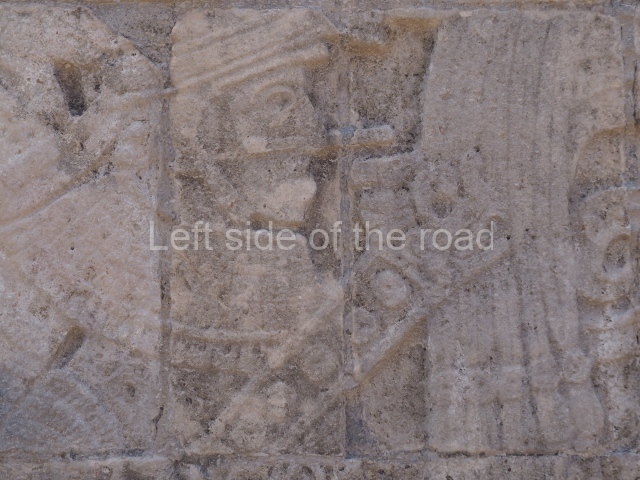

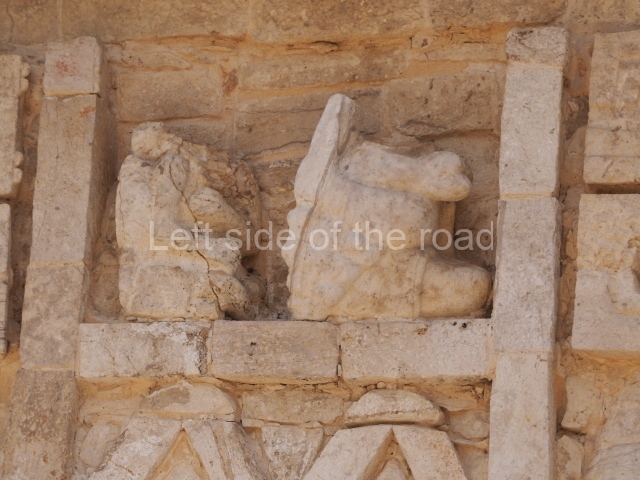

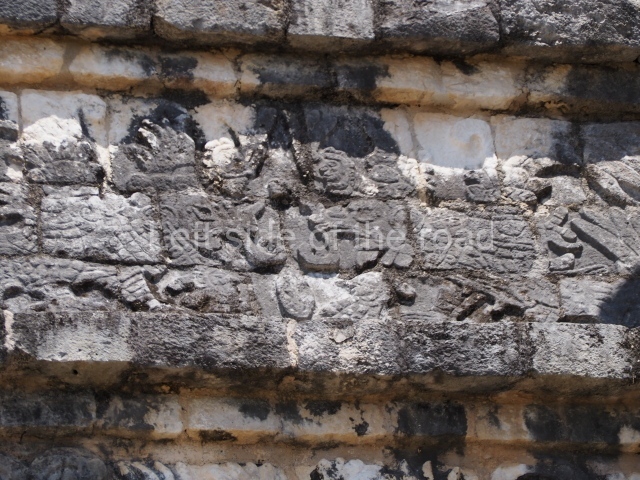

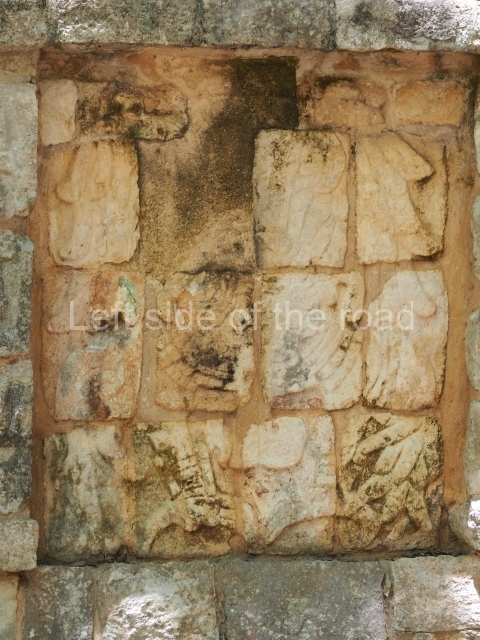

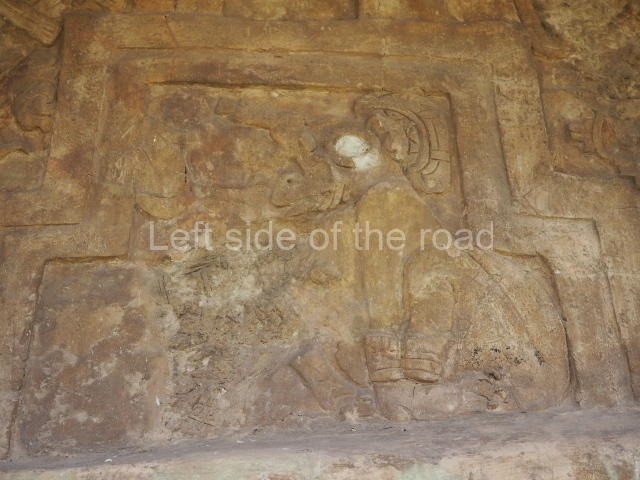

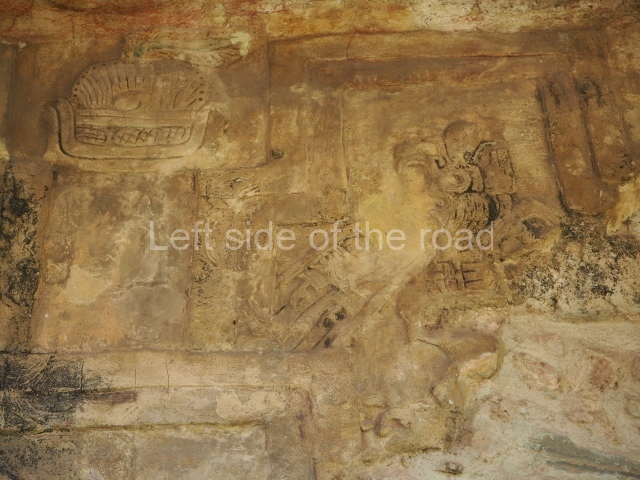

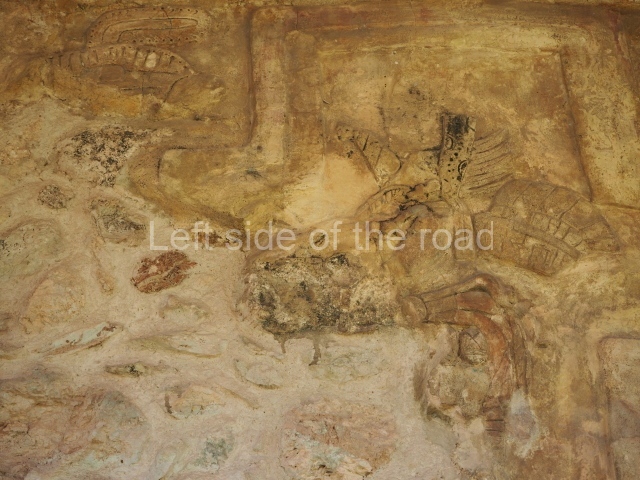

Reliefs and murals represent a highly aggressive, militarised society in which the majority of the figures carry weapons; many of the scenes represented are also of wars and battles. One of the main figures, or group of figures, is associated with the symbol of the plumed serpent (Kukulcan in Maya, Quetzalcoatl in Nahuatl), which also plays an important role in the decoration of buildings and works of art, accompanied by eagles and jaguars, the Chac Mool seated figures who fulfil complementary functions in certain temples and galleries, standard-bearers, tall and short telamons, etc. The objects for daily use and worship tend to be of good quality and finely finished, as are the technical details on the building facades. Technical experiments, especially in the use of tall, slender columns, interior staircases and other features, have produced large covered spaces that had never before been possible. This period culminated with evidence of destruction and reoccupation, with a predominance of poor quality ceramics, such as those that characterise the lower echelons of the new centre of power in Post-classic Yucatan – Mayapan. Building activity was reduced to a few changes and adaptations and the level of occupation declined dramatically.

During the Late Postclassic there was even less activity in the core area of Chichén Itzá. There is evidence of ceremonial activities in the rubble of the tall buildings, but these were obviously in ruins by then, perhaps retaining the odd bay for the performance of ceremonies in which the Chen Mul effigy incense burners and small tripod bowls of the Mama Red variety played an important role. Large quantities of offerings have been uncovered at the Sacred Cenote, confirming reports by Bishop Landa that Chichén Itzá was an important site of pilgrimage at the time of the Conquest. We still lack complete information about the density of the permanent population but there must have been one or several towns near the ruins of the former great city because when Montejo Jr. tried to establish a colonial holding there he was forced to retreat to the coast. Landa explored the part of the site between the Castillo and the Sacred Cenote, where a processional path remained in operation until the Inquisition trials of 1562. When brothers Alonso Ponce and Antonio de Ciudad Real visited the site some 20 years later, Chichén Itzá had already become a ranch. The town nearest the ruins is still Piste, built on the western section of the ancient city. All the excavated and restored buildings date from the periods of Chichén Itzá’s greatest splendour, with a notable emphasis on the constructions in the so-called Modified Florescent style. This is true of the Great North Platform but also of the architecture throughout the site, including in particular the group of buildings with inscriptions a little further south around the plazas associated with the Casa Colorada (‘Red House’), the Caracol (‘Snail’) and the Nunnery.

Site description

The archaeological city is one of the largest in northern Yucatan, covering over several square kilometres, albeit without the uniform density or grid system of some of the other cities on the plateau, in the cultural area of Mesoamerica. It is also difficult to delimit the site with total accuracy, because in many cases it is not clear whether the small residential groups that cover the entire city like a mesh and the secondary groups visible form part of one of the “recorded” sites or the next one. The largest nearest site is Yaxuna, 11 km to the south, which is in turn linked by a causeway over 100 km in length to the city of Coba, in the state of Quintana Roo. Approximately 50 km north-west of Chichén Itzá lies Izamal and at almost the same distance to the north-east Ek’ Balam, both cities with enormous constructions that are beginning to occupy their rightful place in pre-Hispanic history due to their epigraphy, iconography and recent archaeological projects.

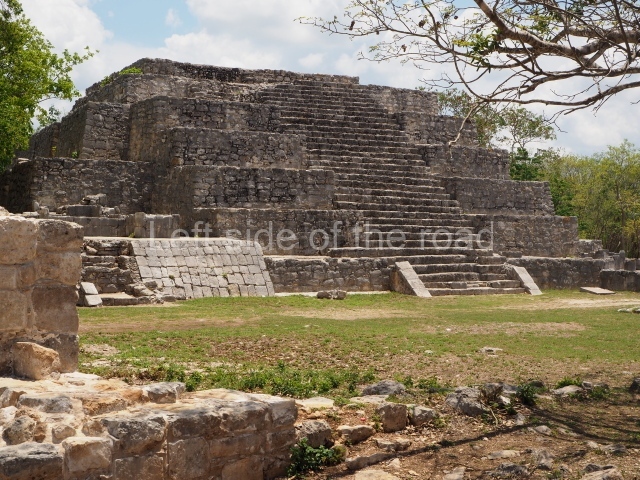

The nearest of the huge salt pans on the north coast is just under 100 km away, and the entire perimeter of the peninsula, both in the south-east and south-west, is populated by coastal trading centres and other relations that connected Chichén Itzá to the Mesaomerican world in its day. Large areas in the centre of the peninsula are given over to the cultivation of maize, beans, cotton, fruit and other crops, and now that the supply of water had been controlled market gardening is possible. Chichén Itzá and its populated area, with its aforementioned lack of uniformity and grid system, encompasses at least 4 km along the north-south axis and 5 km along the east-west axis. The largest and tallest buildings are concentrated in the core area, but there are other medium-sized buildings distributed throughout the site, at distances of between 200 and 700 m from each other and from the city centre. In the middle, situated around the formal groups with their vaulted buildings and own platforms, are the low remains of residential units of a very different density: mainly rectangular houses with adjacent constructions that were probably used as kitchens, laundry rooms, barns, shrines, etc. Numerous residential units have been recorded but very few of them have been properly excavated as the limited funding has tended to be used for correcting the aforementioned deficiencies of former excavations.

Chichén Itzá must have boasted a considerable population, judging from the size of the city and the number of houses, not to mention the vast quantity of expertly made and artistically sculpted stone constructions and the numerous ceramics in the large refuse dumps found all over the site but especially around the platforms. The remains of other crafts made of stone, wood and textiles – either local or imported – have been found inside the Sacred Cenote or as part of the representative art of Chichén Itzá. Apart from craftsmen, it is logical to suppose that there were numerous experts in rituals and ceremonies, in war and in the administrative control of the city, in local and long-distance trade, and in daily maintenance and farming, perhaps combined with control of the water in the cenotes.

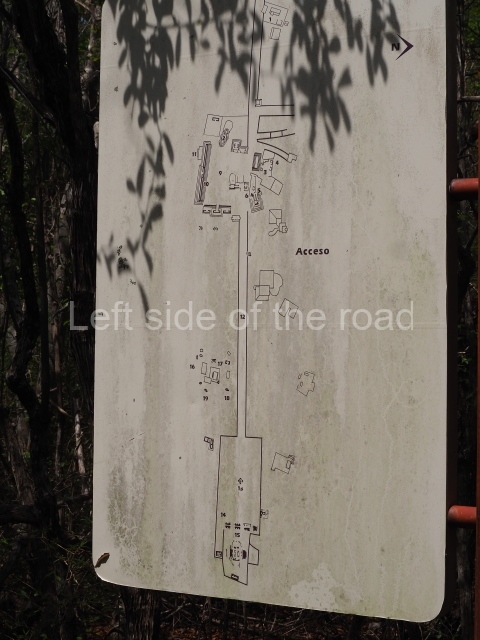

One notable aspect of Chichén Itzá is an internal organisation element that is characteristic of northern Yucatan in general: a large network of slightly raised paths – known as sacbeob in the Maya language – delimited by rows of stones, which connect the different groups with the main complexes and the latter with the core area of the site. This network adopts the form an irregular dendrite, although at the bottom end there appear to be two large north-south and east-west axes, with a slight deviation to the west, possibly as the result of a change in direction over time. Some of the paths are notably straight and there are various elaborate cases of junctions, steps for climbing up or down to an adjacent piece of land, small adoratoriums and complicated bridges for entering or leaving the walled precincts. To date, over 80 of these causeways have been identified, some of them wide, paved and several kilometres long, others almost insignificant, barely 2 or 3 m wide and less than 20 m long, formed simply by the rows of stones that delimit them. In addition to the major internal routes, the sacbeob – mainly the least formal routes – appear to have served the purpose of guaranteeing the dry and safe passage from one raised built area to another, thus avoiding the lower muddy passages through the kankab (red earth), especially in the rainy season.

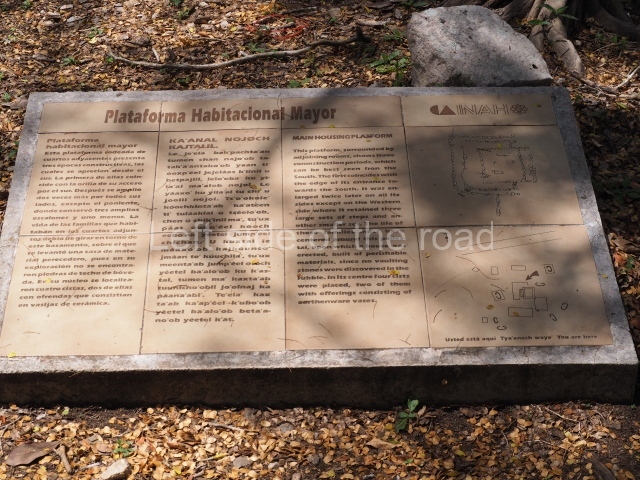

The common population mainly lived in houses made of wood, mud and palm leaves: all that remains of them are a few floors and one or two rows of stones that served as the base for the walls. There must have been a whole scale of fabrication and differentiation between these houses, but being made of perishable materials they have not survived. In certain areas of the site there are dry walls delimiting pieces of land, which suggests that the composition of each plot was variable, possibly based on the varying composition of the family groups that lived there. From these single room dwellings to the so-called ‘palaces’, there is a whole series of increasingly complex constructions made of different combinations of durable materials – in this case, stone – and perishable elements. The greatest variety occurs in the roofing system: there are roofs that must have been made of palm or zacate leaves, as in the simple houses of the present day, roofs with ‘corbel vaults’ as in the large public buildings, temples and palaces, and flat roofs glued into position with wood, gravel and stucco, which were subsequently widely used at Tulum and Mayapan. Most of the single-room dwellings at Chichén Itzá adopted the first system, very few the second one – primarily limited to public and religious constructions – and to date hardly any flat roofs have been recorded.

The buildings erected on high pyramidal platforms have traditionally been interpreted as temples, due both to the limited space available inside them and to their Chac Mool sculptures and telamons for tables or altars, and an internal and external decorative programme based on reliefs and paintings with a strong ideological and religious content. Meanwhile, the grand colonnades and porticoes, simple, double and multiple, have been interpreted as spaces where crowds of people would gather for public, religious, trading and social events that required protection from the sun and rain. The ‘palatial’ groups at Chichén Itzá refer not only to the so-called range or elongated structures, but also to the groups of vaulted buildings with rooms or series of rooms in very different shapes and with different orientations, of which there are several examples. These structures often have a second or even third floor, imitating the great palaces of the central Maya area. At Chichén Itzá they are situated in the core area of the site, but also in some of the secondary groups, such as the Initial Series Group, the so-called Old Castillo Group and several of the large groups at the north end of the site. Most of them were probably residences for the ruling class, the dynasties that shared the political control of the city and state. At the same time, however, they must also have been the scene of all the religious, military and economic activities related to these dynasties and their ancestral objects of worship.

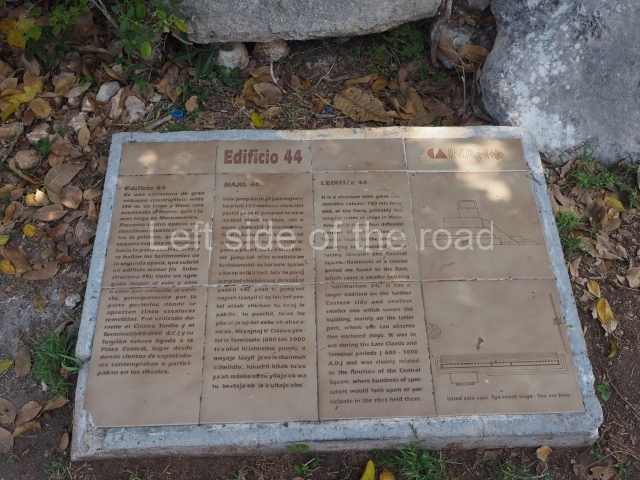

There are several ball courts at Chichén Itzá, mainly I-shaped. There are also other buildings whose function is more difficult to determine – special public buildings whose use has not yet been clarified, such as the so-called ‘gallery-courtyards’ to be found in nearly all the main groups. It seems unlikely that they served as residences. The aforementioned large open areas may have been used as markets or for public gatherings. The platforms are a particularly impressive aspect of the site, such as the one that provides the base for the entire group of buildings around the Castillo and Thousand Columns plazas. The current official tour of the site commences at the Great North Platform, proceeds to the so-called Thousand Columns Plaza, crosses the Ossario Plaza and continues to the vast but subdivided Nunnery Square and Caracol.

Great North Platform

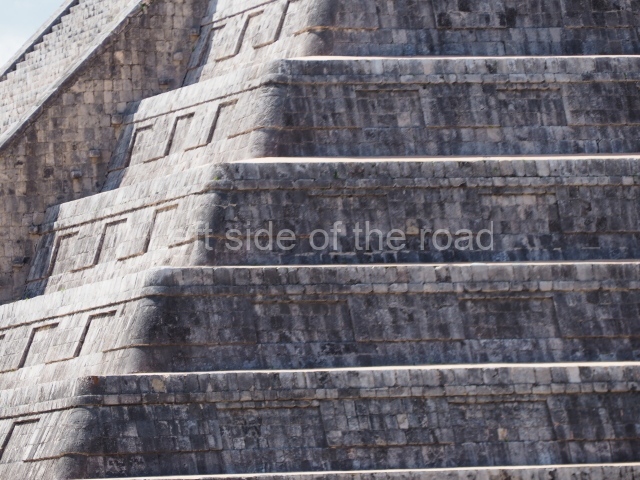

Castillo.

Also known as the Temple of Kukulcan, this is the largest construction at Chichén Itzá, built on a square platform overlooking the city. Together with the Platform of Venus and Sacbe I, it represented the political and religious power in the ancient city. It displays an austere decorative programme, based on the giant plumed serpents on the balustrades. Situated inside it is another temple from an earlier period, facing the same direction which contains a Chac Mool figure and a jaguar-shaped throne with all the original polychromy and inlaid jade.

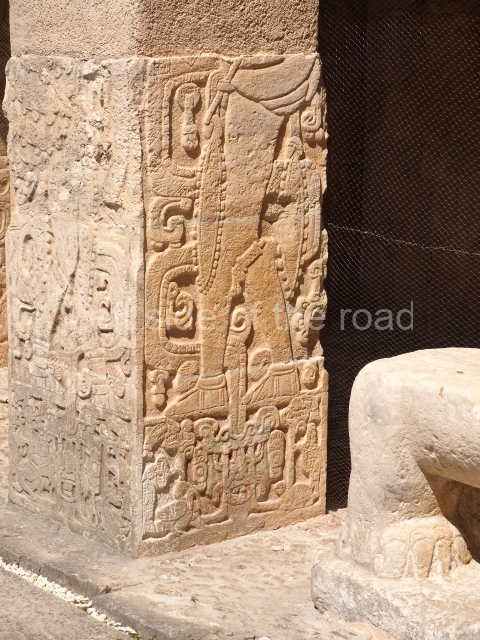

Great ball court

This is the largest ball court in Mesoamerica, measuring 120×30 m. It has two long lateral constructions that sported the stone rings with images of intertwined plumed serpents and sloping benches with scenes of players being sacrificed. The scenes represented probably referred to mythological or historical events associated with the rulers of Chichén Itzá. U-shaped walls seal both ends of the court and provide the base for various buildings richly decorated with reliefs and paintings. Situated at the west end is the Temple of the Jaguars and Eagles, which contains chambers on different levels and walls in which processions of lords and battle scenes offer vivid images of the history of Chichén Itzá.

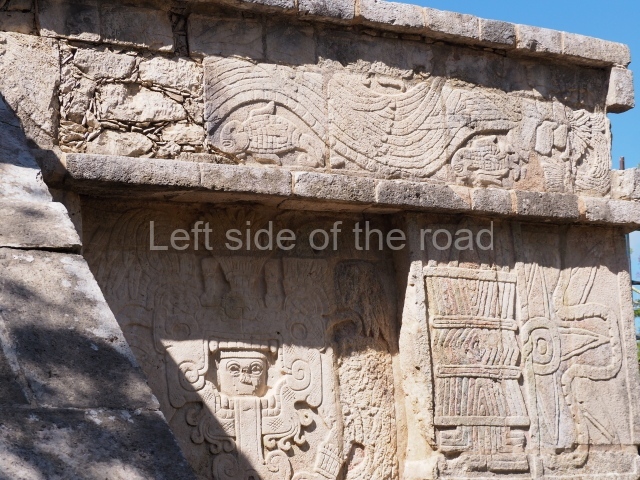

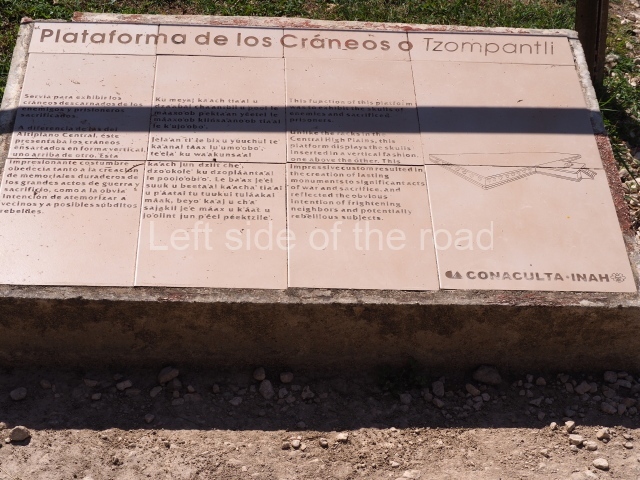

Platform of the Skulls or Tzompantli

The function of this type of building consisted in exhibiting the bare skulls of sacrificed enemies and prisoners, a ritual that was performed in various parts of Mexico. The skulls here have been strung up vertically, one on top of the other. The purpose of this imposing custom was clearly to immortalise great acts of war and intimidate neighbours and potential rebels. Flanking both sides of the entrance stairway are gaunt warriors leading long processions of other warriors garbed in serpents and carrying human-head trophies. The friezes culminate in two rows of plumed serpents.

Platform of the eagles and jaguars

This rectangular platform with four stairways bears a great similarity to the Platform of Venus and other constructions situated on the central axes of the plazas that formed the great city. Plumed serpents climb up the balustrades, while the tableros or panels display recumbent figures and, beneath them, representations of eagles and jaguars holding up what appear to be human hearts.

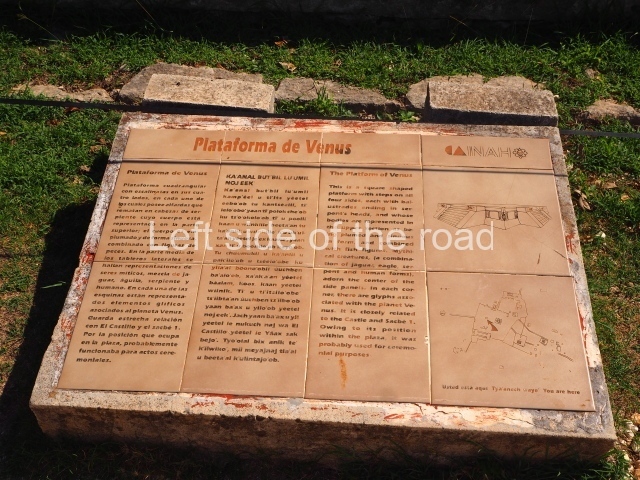

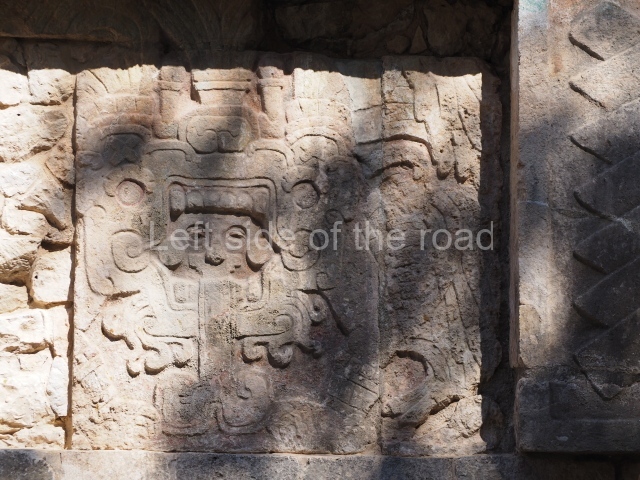

Platform of Venus

This is quadrangular with stairways on all four sides and balustrades culminating in serpent heads. The decorated tableros display plumed serpents and fish; there are also representations of mythical creatures, a mixture of jaguar, eagle and serpent with human features, which have been interpreted as symbols of god, the planet Venus or Quetzalcoatl/Kukulcan as the star of the morning. Reliefs with the ‘pop’ or mat symbol, related to power, recall the political and ritual role that these buildings played, with ataduras or binder-mouldings referring to calendric aspects. There is a strong similarity with the Castillo and the path leading to the Sacred Cenote; according to Landa, this space was used for dances and theatrical events associated with grand ceremonies.

Sacbe 1

This artificial causeway connects the great Castillo platform to the Sacred Cenote. It is 270 m long and 8 m wide. The sides adopt the form of taludes or slopes clad with veneer stones, and small lateral walls ran along the entire length of the path. The processions would depart from the plaza in front of the Castillo and culminate at the Sacred Cenote, where the ritual cleansing of those to be sacrificed and the officiants would be performed by means of a steam bath. The entrance to this causeway was sealed in times of war by a coarse wall, parts of which have survived to this day.

Gallery of the columns

This is a low platform abutted to the inner face of the wall that surrounds the main group at Chichén Itzá. The columns are arranged in a single row and may have supported a sloping roof. Due to its proximity, its function was probably related to Sacbe 1 and the control of access to the Cenote.

Sacred cenote

Known as Chen ku in the Yucatec Maya language, this is a natural, almost circular well which different sources have described as a centre of pilgrimage and offerings, an object of worship throughout the Terminal Classic and Post-classic, when the Maya sent messages to the gods through this ‘door’, especially at times of natural disasters, hoping for a favourable response if any of the sacrificial victims survived. Measuring 60 m in diameter, the water level is situated 22 m from the top with a depth that varies been an additional 6 and 12 m. The explorations undertaken in the waters have uncovered pieces and fragments of gold, copper, tumbaga (an alloy of gold and copper), obsidian, shell, wood, fabric, copal, flint, etc., as well as the skeletons of children and adults. The following structures are all situated at the west end of the Great Plaza:

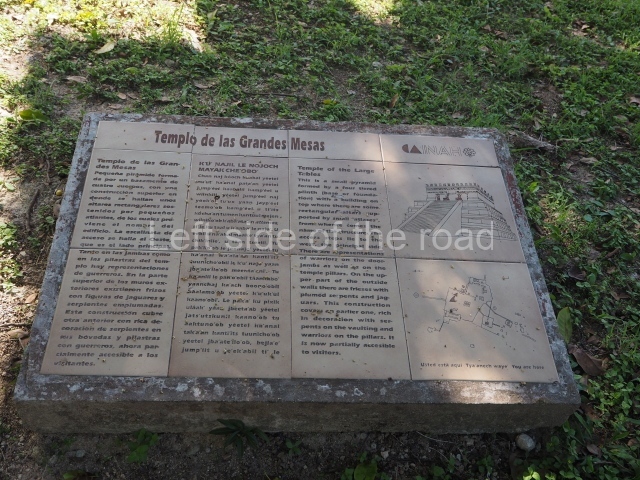

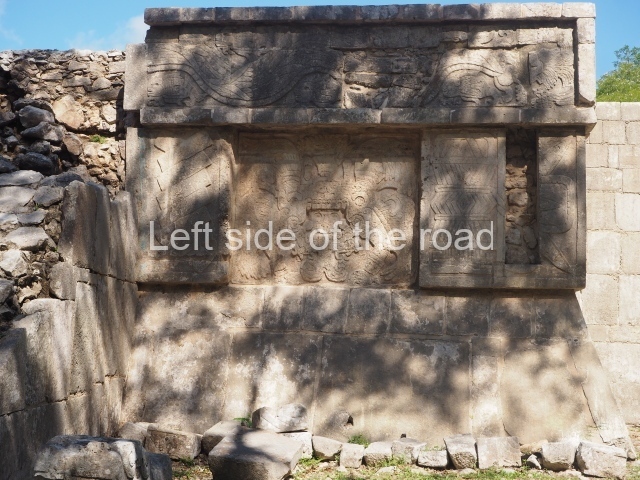

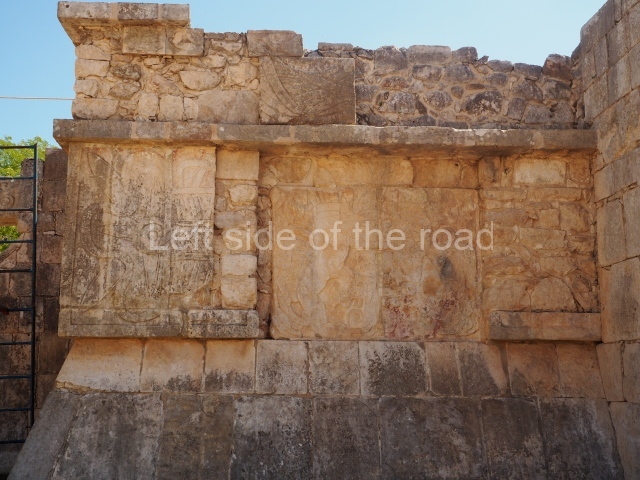

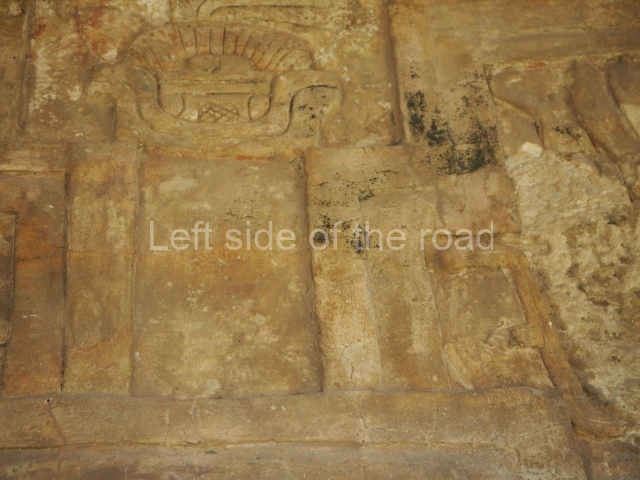

Temple of the large tables

This is a four-tier pyramidal structure that supports a temple with three vaulted-roof bays. Inside it was a long altar formed by rectangular slabs of stone, supported by small telamons with the arms aloft. The jamb stones and pilasters of the temple depict warriors and governors, while the upper frieze of the exterior walls displayed a brightly-coloured scene of plumed serpents framing a procession of jaguars. The building contains a sub-structure in which the vaulted ceilings are decorated with frescoes of serpents and pilasters with polychrome reliefs of warriors.

Structure 2D6

This corresponds to the ‘gallery courtyard’ variety of building and consists of a long gallery with cylindrical columns at the front and a sunken quadrangular courtyard at the rear. Situated north of the Temple of the Large Tables, to which it is closely related, it was probably used by the social group who controlled the functions of former temple.

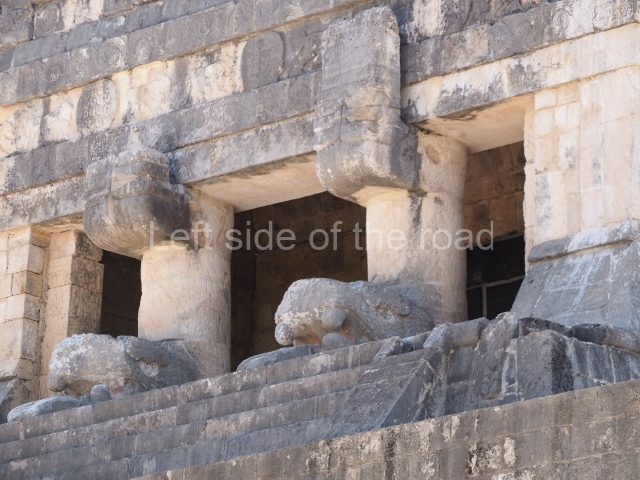

Temple of the warriors

This owes its name to the scores of pillars with reliefs of warriors and prisoners with their hands tied that practically cover the entire surface. The upper temple, which has a tripartite entrance with serpent columns, had eight rooms separated by an inner wall with a table-altar supported by small telamons at the rear. The exterior walls and corners of the temple display giant long-nosed masks and men-birds-serpents with traces of the original polychromy. The colonnade at the foot of the building contains an altar with a sacrificial stone at the front, still in its original place. The generous spaces offered by the colonnades, sometimes with vaulted ceilings of stone, permitted a large number of people to gather for important events and considerably increased the available space for storing goods and equipment. The building takes its name from the numerous figures represented on the pilasters, armed and wearing rich ceremonial garments. Several of the heads of these figures are flanked by iconographic elements which almost certainly represent their names, personal attributes or titles, tribal emblems, military orders or the names of dynasties that represented the new political order based on the alliances between ‘lords’ that was established at Chichén Itzá. This building covers an earlier one known as the Temple of Chac Mool, whose walls still display serpents, warriors and priests in different shades of red, blue, green, ochre, black and white.

West colonnade

This is the longest colonnaded construction at the site. Originally covered by a vaulted roof, its main façade overlooks the plaza in front of the Castillo and a passageway connecting it to the Plaza of the Thousand Columns behind it. It must have been built to accommodate the great multitudes who gathered for festivities, meetings and trading purposes. The passageway leads to the Plaza of the Thousand Columns.

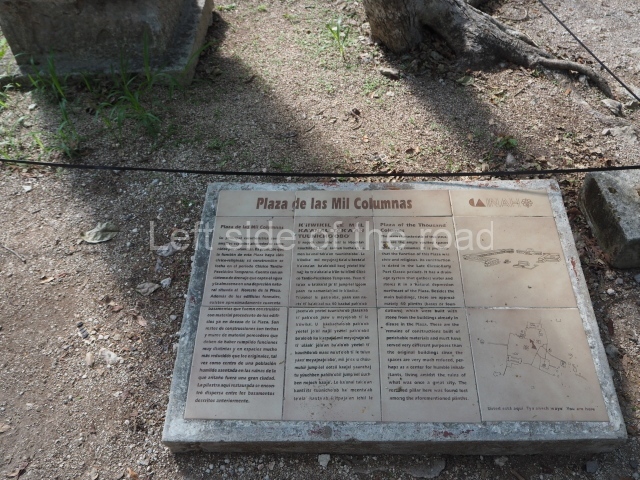

Plaza of the Thousand Columns

This is a large space delimited by colonnades with vaults resting on beams of jabm or sapodillo wood, now lost. Some of the buildings around the plaza are two-storey and probably had a civic-religious function, although another hypothesis is that they were used for commercial or residential purposes. There is a drainage system to collect the rainwater and conduct it beneath the buildings to a natural depression in the terrain situated to the north-east. The plaza contains the remains of numerous constructions built after Chichén Itzá’s boom period.

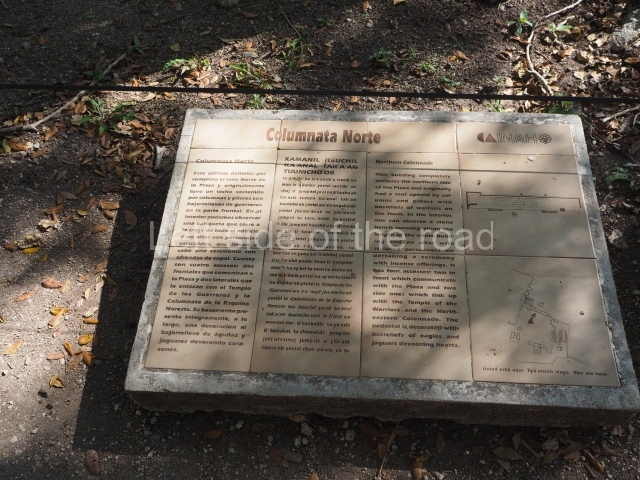

North colonnade

This is situated on the north side of the plaza and originally had a roof supported by columns and pillars with bas-reliefs of warriors. Inside, a bench runs along the building and there is an altar adorned with carvings of figures performing a ceremony with copal (a type of resin produced from plant sap) and offerings. Stairways lead from this space to the Temple of the Warriors and the Palace of Balam Kauil Ahau. There are bas-reliefs of eagles and jaguars devouring hearts.

Palace of Balam Kauil Ahau

This construction contains open spaces between tall columns. It is a unique feature of Chichén in that its name is inscribed on the façade: the bodies of the rampant jaguars bear inscriptions of the Maya glyphs Kauil (the name of a god and also a surname in Yucatan) and Ahau (‘lord’ or ‘governor’), in a combination of the Maya-Toltec style and the classic Maya script and religion. The use of the building must have been closely related to the function of the plaza at its feet because it affords a privileged view of the interior of the colonnade. The east side of the plaza is delimited by a row of buildings arranged on a north-south axis and an adjoining section, the North-East Colonnade.

North-east colonnade

This building comprises five bays and adjoins the east side of the Palace of Balam Kauil Ahau. It is characterised by the pillars that support the vaulted ceilings and the altar in the middle decorated with ritual scenes. Its north platform runs along the side of a deep sinkhole which was clad with stone to contain the rainwater that drained into it from the plaza.

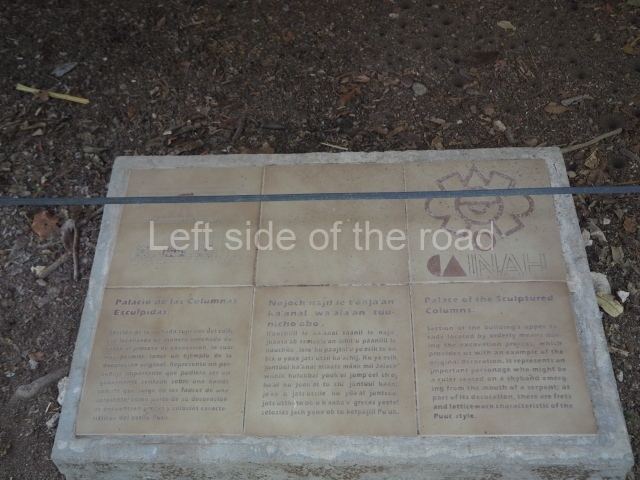

Palace of the sculpted columns

This elongated or range building is one of the most impressive on the east side of the plaza in that its jamb stones and columns display a rich repertoire of over 40 bas-relief figures. There is a gallery at the front and several rooms inside, nowadays with very poor access. Its three upper facades were once decorated with geometric patterns, masks of long-nosed gods and a variety of figures. It is believed to have fulfilled civic and religious functions. A Chac Mool figure with a detachable head and in an usual pose was found opposite a central altar.

Temple of the small tables

This bears certain similarities to the Temple of the Warriors: a wide central stairway leads to two upper rooms with vaulted ceilings supported by pillars with sculpted warriors. Nowadays it has been reduced to a mound covered with rubble.

Thompson’s temple

This is a group of rooms and two storey galleries with an interior staircase; nowadays it has collapsed and is barely accessible.

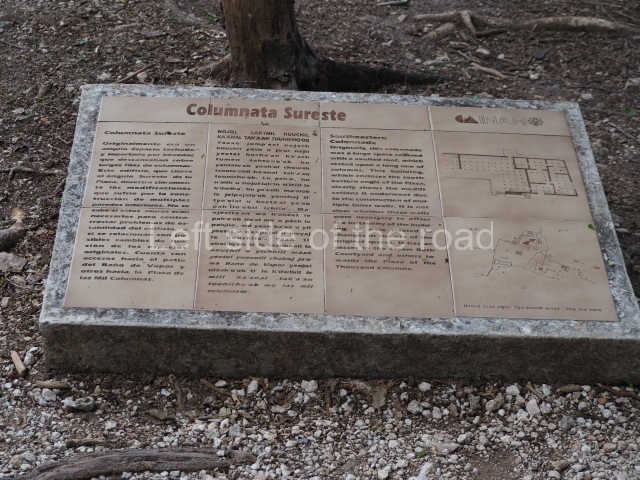

South-east colonnade

This large vaulted space rested on long rows of columns. In its latter days it was subdivided into numerous sections.

Steam bath or structure 3E3

This is the largest of its type excavated at Chichén Itzá. It comprises three sections where steam baths were taken to purify the body for ceremonies or curative purposes.

Market

This is the best and largest example of the ‘courtyard-gallery’ structures. It is related to the events of the plaza, from which it is accessed via a wide stairway. There is a gallery at the front and another one around an interior courtyard with tall columns that supported a roof of perishable materials, which sloped down to the sunken courtyard. The rainwater was conducted along a stone channel. Two benches or altars complete the infrastructure.

Temple of Xtoloc

This takes its name from the Xtoloc Cenote, the second largest cenote at Chichén Itzá, next to which it stands. It was probably used for religious worship and ceremonies associated with the cenote. The pillars of the temple display sculpted figures representing priests and warriors, while the lintel is adorned with plant motifs, birds and mythological scenes. The entrance to the temple faces Sacbe 15, which leads to the Plaza of the Ossario or Ossuary situated to the south-west. Sacbe 5 connects the Plaza of the Thousand Columns to the Caracol and was built in three stages. Along the way, it joins Sacbe 15, which links the Ossario Group to the Xtoloc Cenote. Measuring 120 m in length and 2.5 m in width, it crosses a gateway in the wall around the Ossario platform.

Plaza of the Ossuary

The Ossuary Group occupies a rectangular plaza measuring approximately 150×100 m. It is accessed via sacbeob 4, 10 and 15. Sacbe 10, which has recently been excavated, has two lateral walls and provides the most direct route from the Ossuary to the Castillo.

Platform of the tombs

This funerary space is defined by its columns rising from the bedrock to support a perishable roof. The platform culminates in a frieze decorated with intertwining serpents. There was no stairway, and the two burial chambers inside were reused.

Platform of Venus

The Venus Platform in the Ossuary Group is similar to that of the Castillo, with a flat surface, four access stairways and reliefs of the man-bird-serpent figure thought to represent Quetzalcoatl or Kukulcan as the star of the morning. Also visible here is the pop symbol of power and the corners are adorned with binder-mouldings alongside the plumed serpent and the symbol of the planet Venus, which appears in its Maya form on the upper panels. Traces of stucco confirm that the reliefs were painted red, green, yellow, blue and black. The skull of a decapitated victim with cervical vertebrae attached was found as an offering at this platform.

Round platform

This is one of the few examples of the circular form at Chichén Itzá. An empty box of offerings was found on its west side. Both buildings were probably used as tribunes for ceremonies, rites and dances.

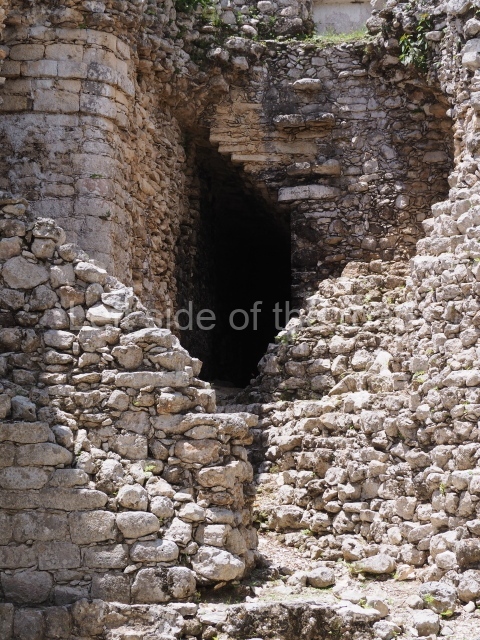

Ossuary or high priest’s tomb

This is a high square-shaped pyramid with four stairways flanked by ascending and descending serpent balustrades culminating in additional serpents covered with symbols, jade and jewels. The platform and upper sections of the building were covered with polychrome stucco reliefs of mythological figures: there are 96 birds with faces of deities and headdresses of human masks facing each other. The panels on the façade of the temple at the top of the platform were adorned with figures of gods or men disguised as the man-bird-serpent and seated figures on sky-blue bands with lots of feathers; the corners are decorated with stacks of long-nosed gods. Situated on the blue paving inside were tables or altars supported by telamons. Semi-kneeling men-birds formed a row across the shrine, which was also full of ceramic incense burners, now broken and abandoned. This temple is particularly important because it is built on a cave to which it is connected by a stone-clad passageway.

House of the Metates and House of the Telamon Columns or mestiza

This building comprises a group of inter-connected rooms with wide porticoes which must have been the residence of people associated with the ceremonies at the Ossuary Group and its maintenance. The Telamon-Columns and their architecture denote that the structure was used by high-ranking people. Immediately to the south and south-east of the Ossuary Group stretches another group of temples and galleries and a ball court which were connected to the large plaza around the Caracol, Nunnery and Akabdzib.

Plaza of the Nunnery and Caracol

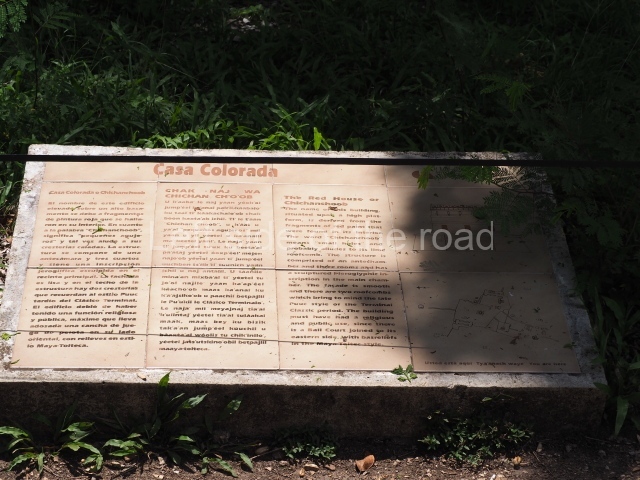

Casa colorada or chjchanchoob

The name of this construction is derived from the traces of red paint found inside. It contains an antechamber and three rooms with a hieroglyphic inscription in the main one referring to date in the second part of the 9th century AD. The roof combs recall the Puuc style. Judging from the ball court on the east side, with Maya-Toltec reliefs, the construction must have had a religious and public function. The group and the plaza which it forms along with the Casa del Venado (‘Deer House’) were delimited by their own wall.

Caracol

This is so-called because of the spiral staircase (‘escalera de caracol’ in Spanish) situated inside, although it is also known as the Observatory because of its supposed function. It displays several construction phases. Nowadays, it is still possible to see a round tower and several aligned but very different square-shaped elements which suggest numerous functions; this hypothesis is also underlined by the long inscriptions. Some historians have also suggested that there is a series of alignments in the three upper windows related to the events of the night sky, such as the passage of Venus and the setting of the Sun at specific times of the year.

Temple of the panels

This is situated on the east side of the plaza on a high platform fronted by a colonnade, in the same style as the Temple of the Warriors. It takes its name from the north and south panels of the colonnade, which depict scenes with important personages, animals and plants, both real and mythological. The offerings rescued during the excavations are associated with the fire ceremonies that were performed in the temple.

Akabdzib

This is a very compact palace comprising rows of bays whose decorative programme includes Puuc elements such as the friezes with bevel-edged mouldings. The construction has 17 rooms arranged symmetrically around a central block. In one of the rooms on the south side is a lintel on the lower part of which is a carving of a governor, official or head of a dynasty on his throne with a jar in front of him and a glyphic text that mentions ‘Yahaual Cho’… the divine Cocom’ and dates from around AD 869/870; one specific date is ’11 Tun 1 Ahau’ (AD 880), probably a reference to the inauguration of the building.

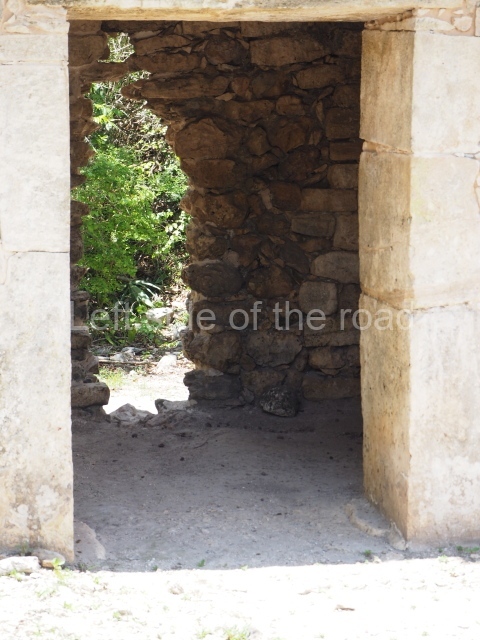

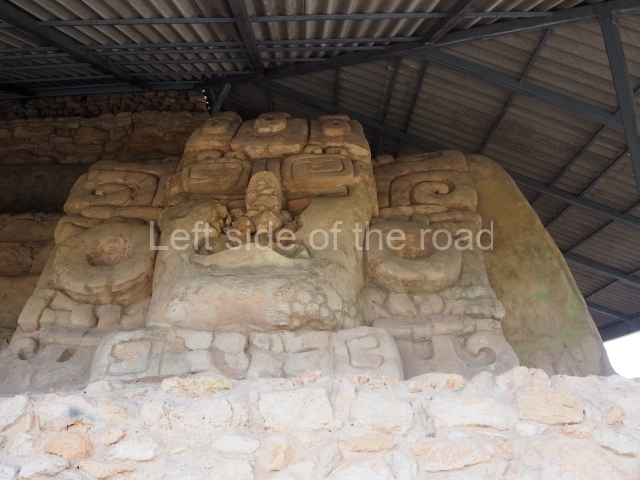

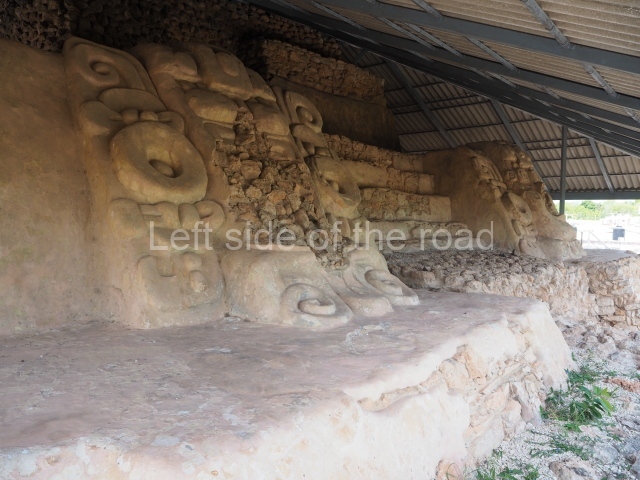

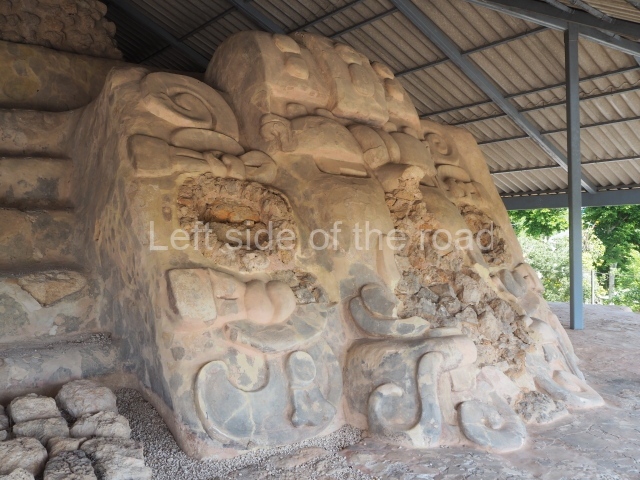

The Nunnery

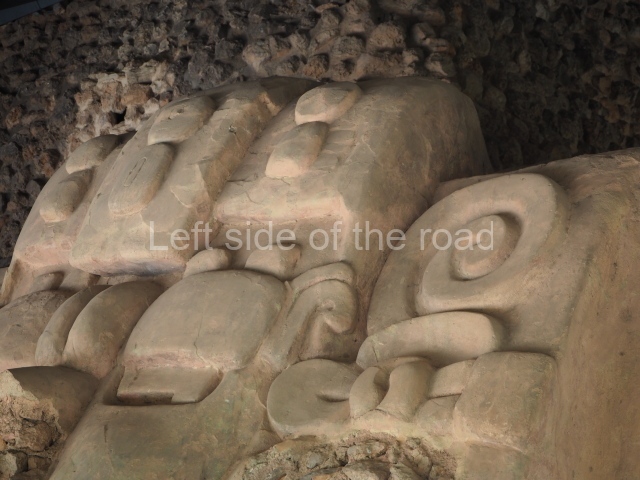

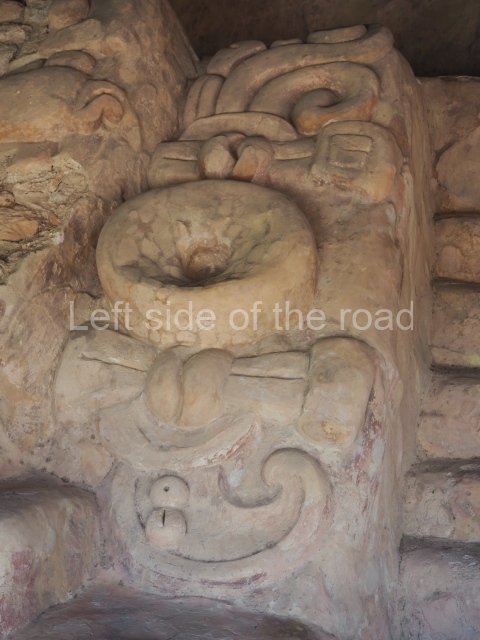

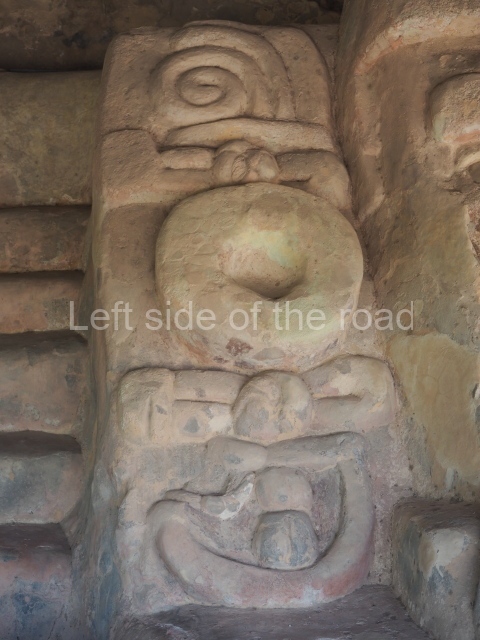

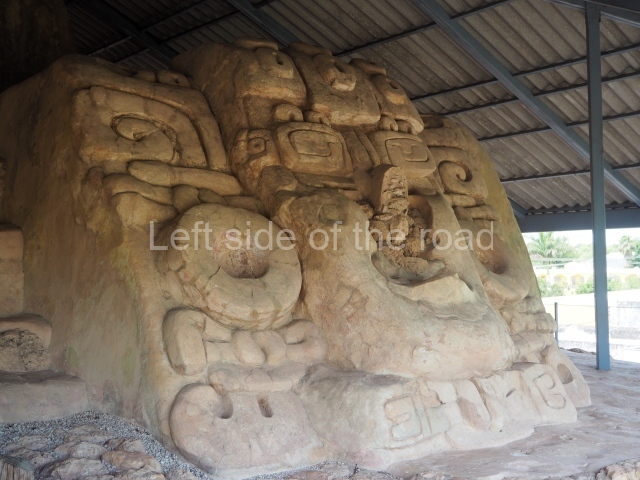

This monumental group lies south of the central platform and contains its own palaces, ball court and a low wall. The main construction, with a temple on the second tier, has rich mural paintings inside and stone mosaics on the outside, in the Late Puuc style. There is evidence of at least six construction phases. The date AD 880 is repeated several times in the long inscriptions on the second tier lintels. At a later date, a small room was added at the top, forming a type of third tier. The jaguar-shaped throne and a stone for human sacrifices visible from the plaza are highly evocative of the ceremonies associated with this building. The courtyards which lie east, north-east and south of the Nunnery have single storey buildings that may have been used as the residence for a dynasty or high-ranking group; there is also a ball court with benches decorated with reliefs. The east facade of the so-called Annexe displays a profusion of long-nosed masks and at the middle a figure seated on a throne of feathers and monster mouth door, distantly recalling the Chenes style in the south-west of the Yucatan Peninsula, from where the Itzá people originated. The inscription refers to a date on the solar calendar and mentions several planets.

The church

This small building with a single room is thus called because of its proximity to the Nunnery. The upper facade is profusely decorated with long nosed masks and the four bearers of the corners of the sky (pauahtunes); the central mask incorporates an important personage. The function of this building is not known, but it is one of the finest examples of the architecture similar to the Puuc style at the site.

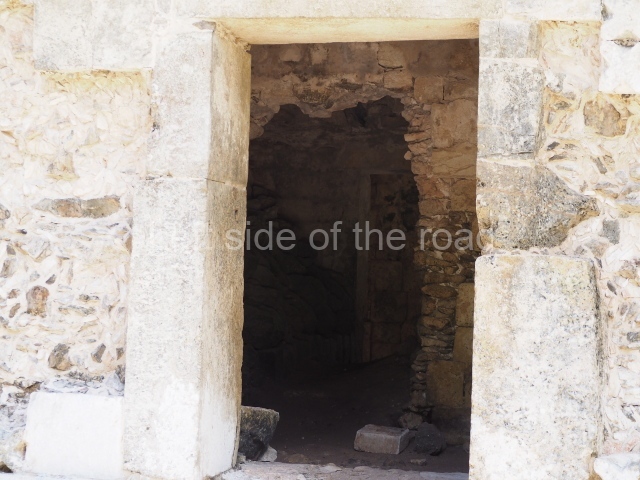

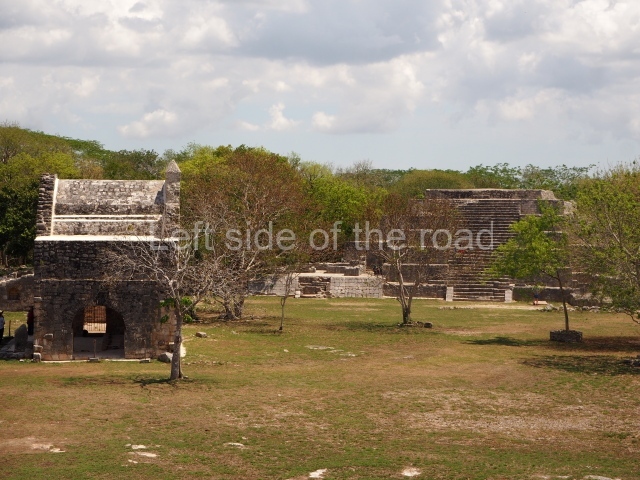

Old Chichén Group or the Initial Series

Situated nearly 800 m further south and connected by its own causeways is the Old Chichén Group, accessed via a large vaulted gateway on the north-west side. It must have played an important role, possibly as the seat of one of the ruling dynasties at Chichén Itzá. It has its own series of buildings which cover all the urban functions.

Temple of the initial series

This temple displays four remodelling phases and occupies the north-east section of the group. One of the lintels, the upper part of which was re-used, shows the only Long-Count date that has been identified at the site: 10.2.9.1.9 Muluc 7 Zac, which corresponds to 30 July 878. The structure is part of a group of buildings that form one of the most important secondary centres at Chichen. The excavations of the interior uncovered the foundations of what is to date the earliest evidence of standing architecture at Chichén Itzá (Temple of the Stuccoes), dated to approximately AD 650. This temple was probably used for civic and ceremonial purposes, functions which it retained despite the remodellings until the end of the history of Chichén Itzá in the Late Postclassic.

House of the phalli

This palatial complex is another structure with several construction phases; it probably began as an elongated building, like those of the Puuc style, and was extended by the addition of numerous rooms around one or two open courtyards. It takes its name from the phallic representations on the walls. A second storey was added to the original building and a gallery defined by pillars with warrior reliefs. There are also two telamons that support a tripartite entrance, above which sits a frieze depicting a personage emerging from a tuber. This central figure is flanked by symbols associated with the origins of the world and descendants, which extend to adjacent building known as the House of the Snails because of a row of these mollusks on the moulding.

Temple of the Owls or Gallery of the Monkeys

These richly decorated buildings delimit the south and west sides of the west Initial Series plaza. They consist of a temple with an inner shrine and gallery with two long bays decorated by the motifs from they take their name. In the corridor between them is the most elaborate chultun or cistern at Chichén Itzá, while the section behind the Gallery of the Monkeys has one of the most impressive high walls at the site. During the time it was used, over half a million flower pots accumulated there!

Other groups

In the southern part of Chichén Itzá, on a platform reached via Sacbe 7, are three buildings with important inscriptions.

House of the four lintels

Although this building has virtually collapsed, it is still possible to see the carefully carved inscriptions on the lintels, which have been preserved in situ and depict mythological creatures, such as the knife-bird and plumed serpents, as well as references to fire ceremonies. The date mentioned is 13 July 881.

House of the three lintels

This rectangular building contains three rooms with carved lintels displaying glyphic inscriptions of the date AD 879. It has long-nosed masks and colonnettes and lattices on both the lower and upper sections of the facade. An earlier platform beneath the floor of the building we see today revealed the skeletons of people buried in stone cists with offerings that date from around AD 600-650.

There are other groups of large buildings in numerous places at the site, such as the old Castillo and Cruces (‘Crosses’) groups in the south, and a large number of similar concentrations in the north-west and north-east of the site. As we have seen, the presence of different architectural ‘styles’ at Chichén Itzá does not follow a simple, clearly defined sequence, but rather a gradual change when one set of elements was replaced by another during a process that was not uninterrupted but characterised by the incorporation of new concepts, some of which correspond to phenomena that are very similar to those that occurred far away at more or less the same time. The elements did not all change at once or at the same pace, and there are no visible absolute local separations at the site, between the early, middle and late sections, but rather trends and prevailing features at different points that nevertheless still belong to the same great city and polity.

Peter J. Schmidt

From: ‘The Maya: an architectural and landscape guide’, produced jointly by the Junta de Andulacia and the Universidad Autonoma de Mexico, 2010, pp 400-411.

- Great North Platform; 2. Castillo; 3. Platform of Venus; 4. Tzompantli; 5. Great Ball Court; 6. Sacred Cenote; 7. Temple of the Large Tables; 8. Temple of the Warriors; 9. Plaza of the Thousand Columns; 10. Plaza of the Ossuary; 11. Caracol; 12. Plaza of the Nunnery.

Further Information:

Getting there:

It’s not really how but when. The aim should be to get to the site as early as possible. The ticket office opens at 08.00 and if you are there before that you will have a short time before the site becomes overwhelmed with organised tours from the main resorts of Cancun or Playa de Carmen. I stayed in the small village of Pisté, which is about 2 kms north of the site. In theory combis call into Chichén Itzá on their way to Valladolid – in practice perhaps not. A taxi from Pisté will cost in the region of M$70 but gets you near enough first in the queue if you leave the village at 07.30.

If you arrive with luggage you can leave your bags at the Official Left Luggage which is on the left hand side of the entry hall, just after the ticket booths. Small bag US$3, large US$6.

GPS:

88d 34′ 01″ N

20d 41′ 05″ W

Entrance:

M$614

To avoid the queues you can pay, by card, at automatic machines that are just behund the left hand side ticket booths.