Dzibilchaltun

Location

The archaeological site lies 15 km north of Merida, very close to an old hacienda known as Dzibilchaltun and the town of Chablekal. It is also very close to where the farming land ends and the tzequeles or hard rock area begins, and then the mangroves, marshlands and sandy beaches of the north coast of Yucatan. This explains why during the pre-Hispanic period the site developed a marine and coastal economy, reflected in the remains of fish, mollusks and animals typical of the area found during the archaeological excavations. In any case, the principal means of survival at Dzibilchaltun was farming, and maize the most important crop. The geographical environment is characterised entirely by flat land in a karst area with sources of underground water: cenotes or natural wells, larger pools of water on the plains and caverns in the subsoil caused by filtrations of water from the surface as a result of the force of gravity.

Pre-Hispanic history

The timeline that the experts proposed for Dzibilchaltun stretches from 500 BC to AD 1600. This interval of time – over 2,100 years – is subdivided into four long periods and one shorter one: the Preclassic, the Early Classic, the Terminal Late Classic and the Postclassic. A period of decline occurred in the Late Postclassic, finally giving way to the colonial period. The excavations at Dzibilchaltun furnished various carbon 14 dates and a single stela, no. 9, dated to AD 830. A wooden lintel at the Temple of the Seven Dolls was carbon dated to around AD 450, give or take 200 years. Thanks to the study of ceramics from approximately 700 rooms or dwellings, as well as 15 buildings and several other carbon 14 dates, including the dates of the Mirador and Komchen, it has been possible to establish a timeline in the area based on the most significant changes in the development of this ancient centre. During Tulane’s research at Dzibilchaltun, 8,400 constructions were recorded and stratigraphic wells were excavated at 400 of them. These uncovered the pre-Hispanic structures in a small section of the core area, permitting the immediately adjacent area to be recorded. The first map was also drawn up comprising 19 sq km of the large residential area, as a result of which the ceremonial centres at ancient pre-Hispanic settlements are nowadays regarded as urban centres. Until then, minor sites were classified as second or third-class settlements, with the exceptions of great sites such as Chichén Itzá, Uxmal and Mayapan. At Dzibilchaltun, the core area comprising the residential buildings of the administrative and religious elite was surrounded by another group of smaller buildings, connected to the central areas and the water at the Xlacah Cenote by various causeways. One of the tallest buildings in the core area, Structure 89, stands 300 m west of the South Plaza.

Site description

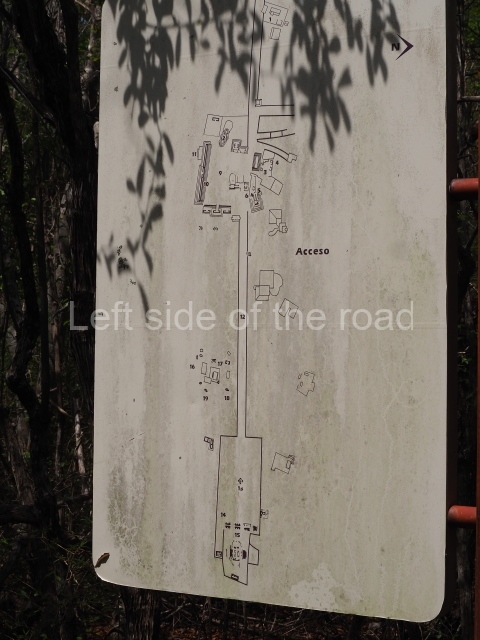

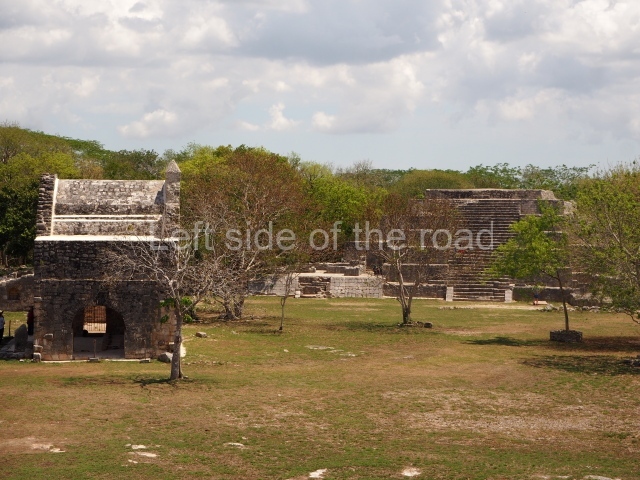

The core area of Dzibilchaltun is defined by a series of plazas: Plaza 1, which is the largest one and occupies the centre of the site; Plaza 2, known as the South Plaza, situated south-west of the former plaza; and a third plaza which lies west of Plaza 2. In the middle of the large central plaza are the remains of an open chapel, which appears to have been built by 1590. The date 1593 is inscribed on the stone friars’ house. Situated in the same plaza, next to the cenote, are the architectural remains of what was an old cattle shed. There is evidence of a succession of smaller pre-Hispanic settlements around Dzibilchaltun, many earlier than the former and others later, but as suburbs it is difficult to differentiate one from another. It was for this reason that the first map drawn up encompassed such a large area, namely 19 sq km.

Central plaza.

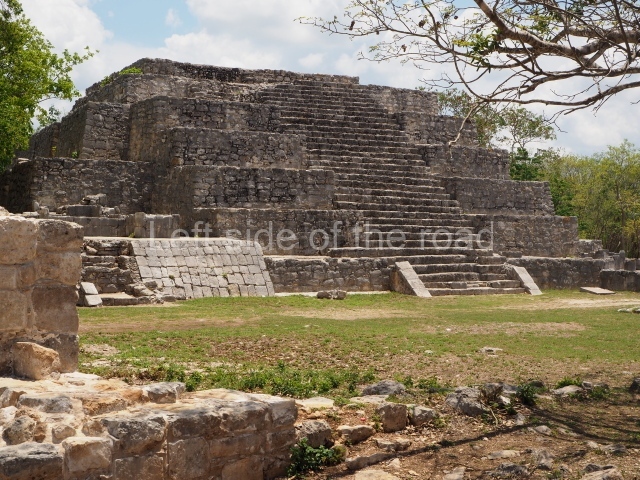

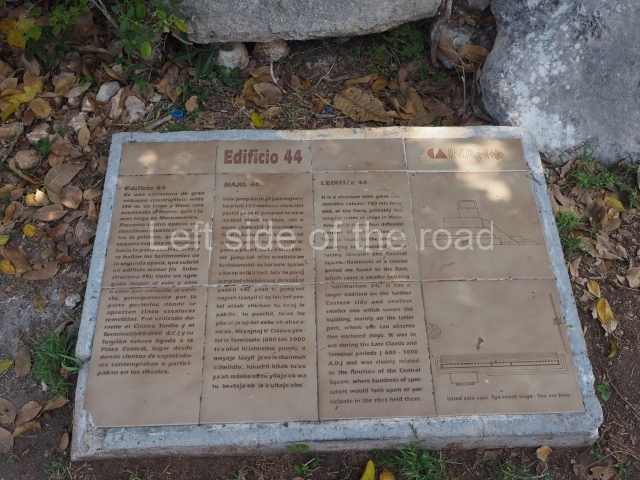

The plaza has a surface area of approximately 12,240 sq m and it had stucco paving. Of the buildings around it, the most outstanding is Structure 44, which has a long stairway and seals the south end of the plaza. It is also the longest building at the site. Situated on the east side of the plaza is Structure 42, a large platform which measures approximately 67×22 m and stands nearly 4.7 m high. A longitudinal series of vaulted rooms formed the first construction phase of the building. The central section was subsequently extended eastwards and upwards, with a new, narrow stairway at the centre leading to the plaza. The west side is partly delimited by Structures 45 North and 45 South, which contain several vaulted rooms and sub-structures. The north side is occupied by a series of later buildings. Near the north-west corner stand Structure 37 and the partly excavated Platform 33. Another long, low platform supports structures 39 and 50, much later additions. The north-east corner is defined by Structure 36, a four-tier pyramidal building that stands 9.4 m high. All the stairways on these constructions face the central plaza, lending it a very identifiable appearance. Situated behind Structure 37 is Structure 38, actually formed by a group of three structures on a terrace that has been dated to the Late and Terminal Classic (AD 600-1000). Most of the architecture around the central plaza dates from the Late and Terminal Classic, with the exception of two smaller constructions situated to the north (39 and 50), which correspond to the Early Postclassic (AD 1000-1200).

South plaza

This space is situated immediately south-west of the Central Plaza and must have been just as important. It is bordered to the north by Structure 55, to the east by Structure 46 and the west by Structure 97; Causeway 4 runs along the south side, and immediately behind it Causeway 6, which leads to Structure 89. Building 46 is the most imposing construction in the area and sealed the east side of the plaza. To reach its final dimensions it passed through several construction phases. The penultimate phase seems to correspond to that of the Seven Dolls, while the earliest phases are buried deep in the building.

Path network.

During the excavations conducted at the site by Tulane University, 11 artificial paths (sacbeob) were found, most of them leading to the centre and linked to the groups of constructions around the edges of the site, lending an urban status to the settlement. Their length varies between 28 and 1,200 m, but the average width is approximately 15 m. The causeways are associated with the political and social organisation of the community and connected the three large plazas at the site when people congregated in them on specific dates and special occasions. Sometimes, for very specific events, these people would have travelled to Dzibilchaltun from other nearby sites. The width of the causeways seems to support this hypothesis, as does the way they stretch from the central plazas to the four cardinal points.

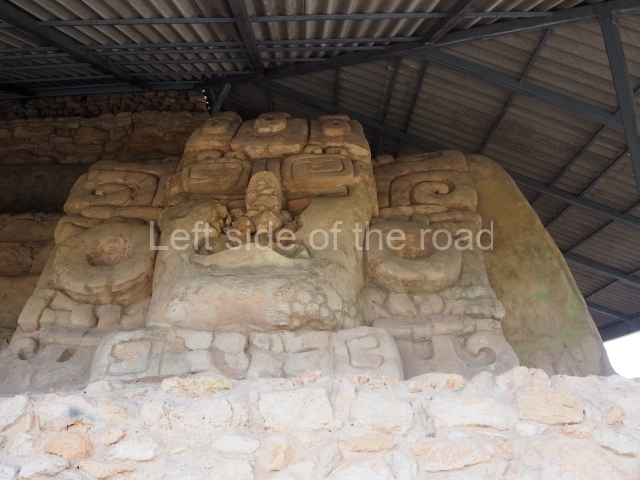

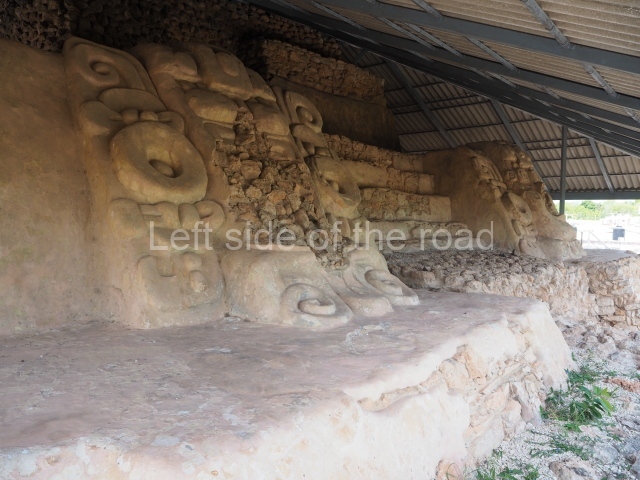

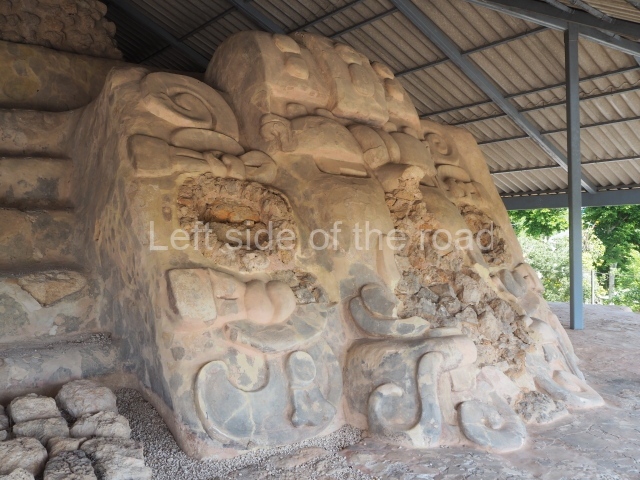

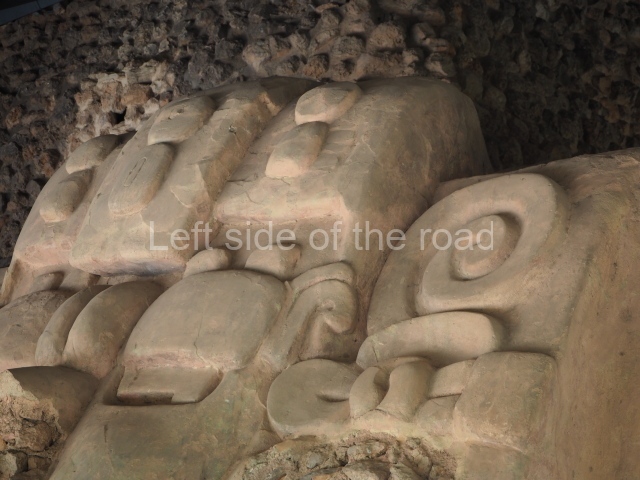

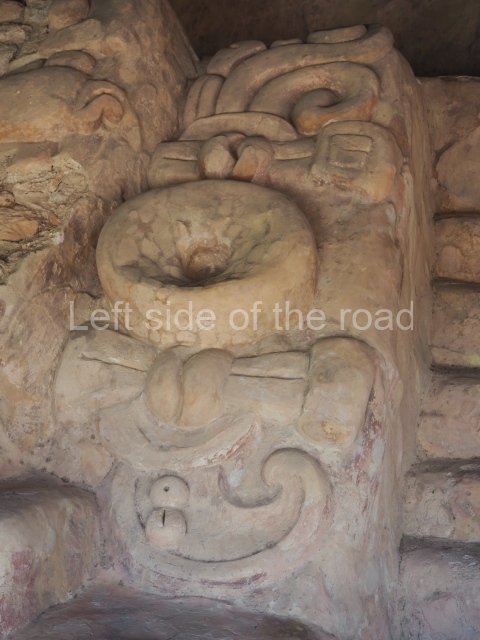

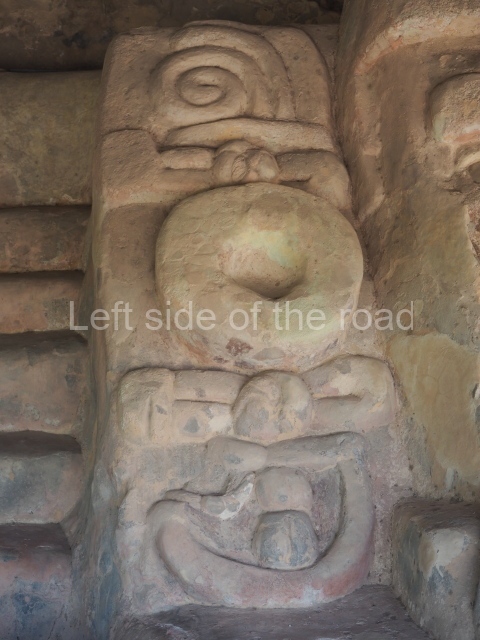

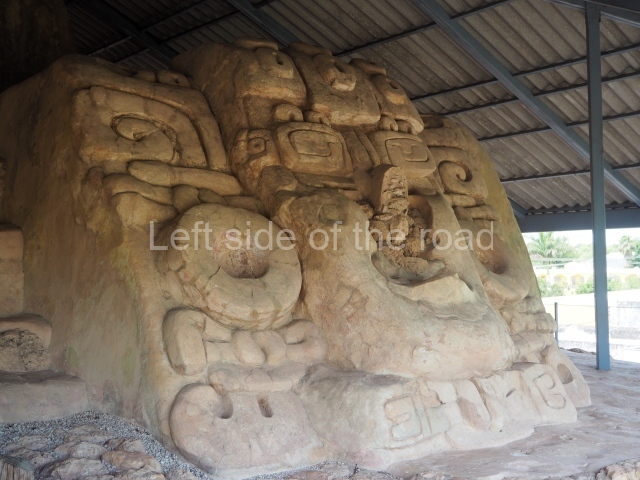

Temple of the seven dolls

This is a quadrangular construction with a central chamber, surrounded by a vaulted gallery accessed on all four sides by stone stairways. The ceiling of the central chamber formed a type of projected tower above the building. There are four entrances and a window on each side of the west and east ones, plus another window further south, above the tower, all of which lends the construction the appearance of an astronomical observatory. It stands on top of a pyramid platform with inset corners. The frieze of the building was decorated with eight stucco masks on a stone carved base, with two intertwining serpents and other elements such as glyphs, beads, feathers and marine creatures in moulded stucco. The building takes it name from a late offering of seven dolls, coarse clay figures, found inside it. Structural faults in the building probably explain why in the late 9th century the temple was filled in with stones and covered by another large building, whose remains still partly cover it.

Adjacent rooms.

Opposite the Seven Dolls, towards the west, is a row of double-bay rooms and one single-bay room. Underneath the floors in several rooms, offerings of shell, fish bones, stingray spines and small pieces of jadeite and grey obsidian have been found, as well as a large quantity of semi-worked marine material, used for making ornaments. The rooms were inhabited around AD 800.

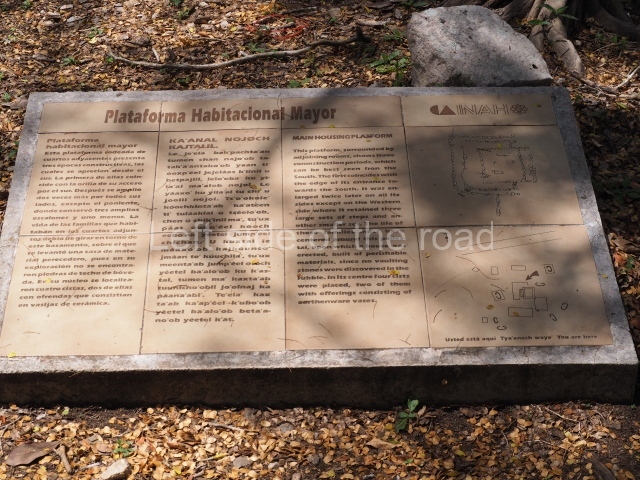

Residential area.

This domestic group very close to Causeway 1 (south side) and the Temple of the Seven Dolls occupies an area of just over 4,000 sq m. It comprises a large platform over one metre in height, situated more or less in the middle of the group; around it are other smaller platforms, three elliptical rooms to the east and a type of stockyard to the north-west. The elliptical rooms with their foundations of large stones and a single entrance are typical of Dzibilchaltun, built either directly on the ground or on platforms. Their walls and roofs were made of perishable materials. The grinding stones and quern stones that are often found in rooms of this type confirm their domestic function.

Ball court

The ball court in the middle of two parallel constructions was of the open variety. The west building made use of an earlier construction while the east building was a totally new construction. There was a predominance of slopes (taludes) and vertical planes on the bench and wall, where the top of the bench rested. The dimensions of the two volumes that line the ball court varied slightly, resulting in an asymmetrical structure. In general, it is just over 20 m long and 12 m wide. It is therefore a relatively small ball court and was a late addition to the site.

Standing temple or Structure 57

In 1941, this was the only building still standing with part of its vaulted roof, and it is from this circumstance that it takes its name. Its construction probably dates from the first half of the 9th century, although there are early architectural characteristics and a few late features. Its walls were finished with finely-cut veneer stones. The door lintels are monolithic blocks similar to those used for Puuc-style buildings, but the vaults are of the corbel variety, although the row at the base of the vault is composed of blocks of stone with carefully embedded tenons to form the incline. It was in use between AD 830 and 1000. Six cists with human remains were found beneath the stucco floor, confirming that this was a residential construction in which the occupants buried their dead beneath the floor.

Ceramics and monuments

During the Late Preclassic the site had Sierra Red, Xanaba and Tipikal ceramics, as well as others. The Early Classic was defined by the Maxcanu and Oxil ceramic groups, and the Timucuy polychromy. During the Late and Terminal Classic, the ceramics were of the slate variety with a coffee-coloured slip. In the Early Postdassic, there were Sotuta ceramics from Chichén Itzá and in the case of tableware Chichén Red, Chichén Slate and Peto Cream Ware. In the Late Postclassic, incense burners of the Navula group, similar to those of the Mayapan group, were typical.

Stelae.

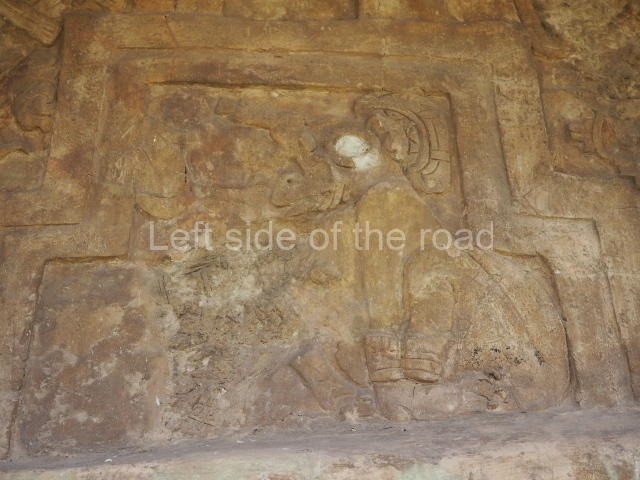

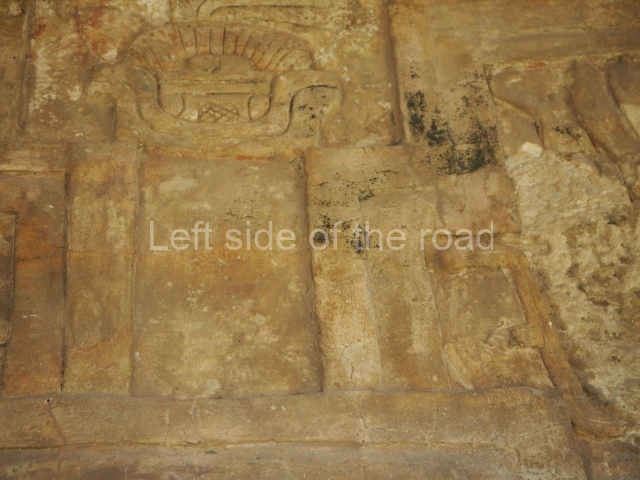

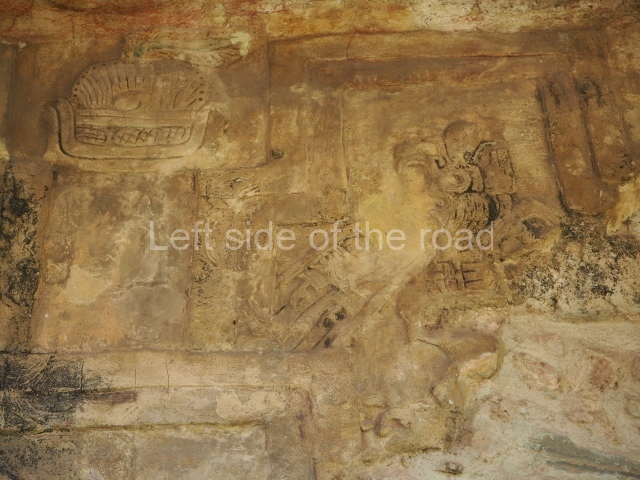

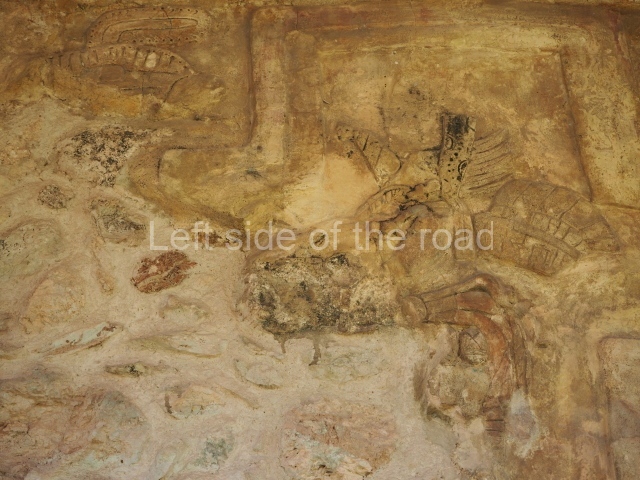

Twenty or so stelae have been recorded at Dzibilchaltun, most of them smooth without any apparent decoration, although they must have been stuccoed, painted and decorated. A handful display reliefs, most notably 9, 18 and 19. The latter bears the emblem glyph of what we now know as Dzibilchaltun, although the real name of the pre-Hispanic city was Ch’iy Chan Ti’Ho’. It also shows the portrait of an important figure, which appears to be Kalom Uk’uw Chan Chac, the governor of Dzibilchaltun during the early 9th century AD, who was buried in Building 42 in the large Central Plaza.

Importance and relations

As the regional capital during its heyday, Dzibilchaltun maintained ties with distant settlements in the Usumacinta and Peten regions, as well as sites such as Edzna in Campeche and Oxkintok in the Puuc mountains. It also had relations with Mayapan and even further east with Chichén Itzá and Ek’ Balam. Finally, it maintained important ties with the commercial port of Xcambo on the north coast, which supplied it with luxury objects for the local elite and other objects from the larger inland sites.

Ruben Maldonado Cardenas

From: ‘The Maya: an architectural and landscape guide’, produced jointly by the Junta de Andulacia and the Universidad Autonoma de Mexico, 2010p, p387-389.

- Access and museum; 2. Central Plaza; 3. Sacbe 2; 4. Sacbe 1; 5. Temple of the Seven Dolls.

Location:

A couple of kilometres to the west of the town of Chabelkal.

How to get there:

From Merida. Colectivo Calle 56, between Calle 59 and 57 – to Chabelkal, then mototaxi to entrance. To return wait for mototaxi (at the main road at the entrance to the slip road to site) back to Chabelkal. (Walkable but will be hot.) Then either a colectivo at stop just off the SW corner of main square or orange bus back to Merida. Bus probably takes twice as long but same price, in May 2023 M$8.

GPS:

21d 05′ 20″ N

89d 35′ 31″ W

Entrance:

M$303