War Memorial, Saranda, Albania

Through its monuments and memorials you can tell a lot about a country, its history, its heroes, its respect for itself, the class relationships, the political balance of power, even the state of the economy.

And there are many examples to prove this hypothesis.

I remember reading a letter written by Vladimir Illyich Lenin asking, in no uncertain terms, why Tsarist memorials and street names still existed in Petrograd (as Leningrad was then known, and not the Germanic St Petersburg as it is now called) less than a year after the October revolution – see Lenin Collected Works, Vol. 44, p105.

I have also seen pictures of the statue of Carlos III being transported to storage on a horse and cart. Carlos Bourbon stood in the Plaza del Sol in the centre of Madrid but was taken down during the time of the short-lived Republic in the 1930s. He was reinstated by the Fascist Franco and still stands there to this day in the time of the so-called ‘democratic monarchy’.

The Plaze del Sol is the traditional meeting place for working class and left-wing Madrileños and the square has witnessed many demonstrations and sits-ins as the people protest the ever worsening economic situation in which an increasing proportion of the Spanish population are having to live. But this is not a problem for the present Bourbon family and Carlos sits on his horse looking down his not insubstantial nose at the hoi polio below with contempt. The situation of the Spanish people will not improve until he is again taken away in another horse-drawn cart, in pieces, to be melted down and the present day Bourbons are taken in a similar cart for an appointment with Madam Guillotine.

One of the images that went around the world after the United States led invasion of Iraq was the toppling of Saddam Hussein’s statue in the centre of Baghdad. The Stars and Stripes flag that was originally covering Saddam’s face was quickly replaced by an Iraqi one (it wouldn’t do to give the impression that he was toppled by a foreign invasion force and not a ‘popular’ revolt) and the edited version is the only one that gets shown now. Imperialism has always re-written history.

In Britain the long-term sycophancy and obsequiousness of the British population is shown by the plethora of statues to different members of the monarchy and representatives of the ruling class that have oppressed and exploited the population over the centuries. To themselves and their struggles the working class have little to look to.

One of the finest is the monument to the ‘Heroes of the Engine Room’. This is on the Liverpool waterfront, just a few metres north of the Liver Building at the Pierhead. This was originally designed to commemorate the men who kept the lights working on the Titanic as it was sinking, having been sealed in to the engine room and with no possible chance of escape. It is still known locally as the ‘Titanic’ Monument, the name being changed to recognise that just over two years after the sinking of the Titanic hundreds of men died in the slaughter of the ‘Great War’ in similar circumstances. Britain is littered with statues and monuments to the incompetent and criminal generals who ‘master-minded’ that particular capitalist and imperialist enterprise but you’ll have to look far and wide to find any others to the ordinary workers turned warriors.

And following that conflict, again in Liverpool, there wasn’t enough money to pay for a permanent memorial to those who had died in the ‘war to end all wars’. They didn’t return to Britain to ‘homes fit for heroes’ and neither to a memorial to their dead comrades. Throughout the 1920s on Armistice Day (11th November) a rickety wooden construction was wheeled out on to St George’s Plateau in Lime Street, decked in red paper poppies for the short memorial ceremony. When there was a bit of money, collected in the main from ordinary working people, the city was provided with (to my mind) one of the finest – if not the finest – war memorial/cenotaph to found anywhere in Britain.

And that brings me to Albania.

During my visits to the country I have attempted to search out the monuments and memorials that were constructed in the period of socialism. Most have been neglected, many have been vandalised, some have been destroyed but many are still in existence and in their different ways tell the story of not only the past but the present in Albania. I will be illustrating and telling the story of those monuments in the future.

So the first one is the small, well maintained but almost hidden and not easy to find (if you don’t know where it is) war memorial in Saranda.

There were certainly memorials in the centre of the town but if they still exist I’ve yet to find them. The language problem (i.e., my inability to speak Albanian) means there are few people to ask and some that might know don’t necessarily pass on their knowledge. The construction that seeks to turn the place into a major tourist destination might have played a role, outright vandalism and reactionary elements would also have played their part.

When it comes to the war memorials I have difficulty in understanding why so many in Albania have been treated in the way they have. I believe the First World War to have been a disaster for the European working class but that doesn’t mean I advocate destruction of the war memorials that are in all but very few cities, towns and villages throughout the British Isles. I’d rather they had died fighting for themselves (as did the workers and peasants in what became known as the Soviet Union) but the lack of any anti-war, Communist leadership and the betrayal by the young Labour Party didn’t make any real and meaningful opposition to the war a viable proposition at the time.

So why have the Albanians allowed their history to be treated in such a shameful manner? More than 30,000 of their people died in the occupations by the Italian and German Fascists. The country’s economy was in pieces, thousands of homes had been destroyed and the isolation imposed upon the country by the victorious imperialist powers because they wanted their own independence meant that they had to build using mostly their own efforts – only the severely damaged Soviet Union coming to their aid.

I might find the answer on day, but I don’t have it yet.

But back to the Saranda memorial.

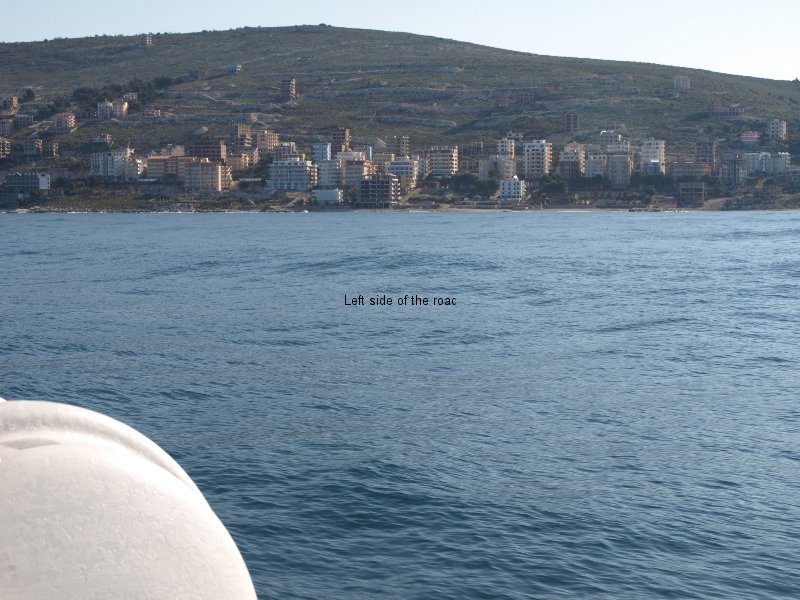

There are only two main routes out of Saranda (apart from the sea route to Corfu), the road to Butrint (the archaeological site dating back to the Greeks) and the Greek border or the road that leads to the rest of the country. It is by the side of this latter road you’ll find the memorial. The road rises steeply after leaving the coast heading up in the general direction of Lëkursi Castle. Once you get to the brow of the hill, with a view of the valley below and the mountains that you have to go over on the route to Gjirokastra to the north, the memorial is slightly above street level on the right, next to an ordinary house.

It’s a strange place for it to be and I’ve no idea if that is its original location or whether it’s been moved there in the last few years. The pillar looks as if it has been made of relatively modern materials, although the plaque with the names and the red star would be the originals.

This is the sort of modest war memorial can be seen all over the country, although some are difficult to find.

The inscription reads: Glory to the martyrs who fell in the liberation of Saranda on 9th October 1944.

‘Lavdi Deshmoreve’ (Glory to the martyrs) was the slogan that was ubiquitous during the time of Socialism, even being set in huge characters on top of the Palace of Culture (now the Opera House) in Skenderbeg Square in Tirana.