To the Indigenous People – Ushuaia

More on Argentina

Indigenous representation in public art – the monuments and photographs

Monuments to the Indigenous peoples

So if the church hasn’t got it right have the civil authorities? I only have a few examples to go on so far but the answer would probably be ‘not really’.

Monument to Indio Tehuelche – Puerto Madryn – Argentina

Indio Tehuelche – Puerto Madryn

The name of this monument in itself says a lot. When Columbus reached the Caribbean he thought he had arrived in India – after all that was the plan of the journey in the first place. He wasn’t looking for a continent that he didn’t know was there he was looking for a quicker route to one he did know existed. That’s why, to this day, that part of the world is still referred to as the West Indies.

But the Tehuelche who lived in, what is now called, the Puerto Madryn area were not ‘Indians’, and the use of the word in the naming of the monument still looks at the world from the Eurocentric approach that was common up to the end of the 20th century – and still not uncommon even today.

But the same stereotype in the depiction of the indigenous people exists further north in Argentina as it did in the south. At least in the area around Puerto Madryn the temperatures get up to a level where the not wearing of clothes makes sense. The day before I left Puerto Madryn the temperatures were in the mid 30s Celsius. On the other hand there was never a full day when I was in Patagonia I did not feel that I needed to have something to protect me from the wind with its cold bite. Being naked in Ushuaia would not have been a life choice – even though the original people from that area would have been much tougher than any foreign tourist – myself included.

Indio Tehuelche – Puerto Madryn

I’m not saying that such an image never represented a Teluelche hunter but it’s the fact that on so many occasions the indigenous people are depicted as being naked which was equated with ‘savagery’ by the Spanish Conquistadors very soon after their arrival in the continent and would also have been the view of the Welsh Protestants who were the first foreigners to colonise his part of Argentina. It’s the ideological position that is being presented which I challenge.

It’s very difficult to know exactly how the Teluelche dressed in their everyday life. A series of photos taken post 1865 when the Welsh colonisers arrived show a variety of dress, some of it sophisticated in design and decoration. Which shouldn’t be a surprise. Such has been found among such hunter/ gatherer groups elsewhere. Much of the clothing was based upon guanaco furs.

The problem is that very soon after the arrival of the Europeans they wanted to mould the local people in their own image. Forcing them to pose in dress which was good for the camera – and would help the photographer to sell the pictures – but not necessarily a good historical record. There was also pressure upon them to change to the woven blanket – in this way a money based market was forced upon the Teluelche which didn’t have such a system of exchange before the late 19th century.

So the male statue representing the Teluelche is naked, all but for a loin cloth, and carries the ubiquitous bow. Around his waist is tied a bolas (boleadoras) – the rope with weights at either end which was used to bring down a hunted prey. (There’s some debate whether the Teluelche used the bolas before the arrival of the Europeans or whether they adapted the practice once it was known to them.) However imperfect and suspect the photographic record might be I have not come across a single picture of a male Teluelche as depicted on the monument. So why choose it?

He has his right hand raised to his brow to shade his eyes from the sun as he looks out to sea. Now why he’s doing this is beyond me. He has hunting weapons which are used against land animals. To the best of my knowledge the Teluelche didn’t live off the sea so why is he looking out in that direction? Awaiting the Gods from the east as thought the Aztecs? Looking out for the Spanish invaders who had caused so much damage on a previous visit. It just doesn’t make sense. So another ‘black’ mark against the Puerto Madryn municipality.

They don’t get many brownie points when it comes to location. The statue stands on a promontory on the very edge of town and would not be seen by many visitors. On the other hand the monument to the arrival of the Welsh sits right in the centre of town, right on the sea front. So marginalisation continues.

Further to this there are two plaques on the plinth of the statue. One commemorates the hundredth anniversary of the arrival of the Welsh in 1965 the other (which didn’t make much sense to me) commemorates the efforts of those who worked for the unification of the ‘aboriginal’ and Welsh culture at the time of that centenary ‘celebration’ – this is dated 2004.

No mention of the Teluelche even on a monument that is supposed to ‘remember’ them.

Yet no street is named after them or not even a symbolic reference to the fact that the land on which Puerto Madryn now stands once belonged to no-one, but was for the use of those who passed through chasing the seasons and the wild animals.

Contrast with the monument to the Welsh arrival in 1865

Welsh Monument – Puerto Madryn, Argentina

As stated above this is in the centre of town, seen and passed by all who visit the city. It’s a monument which tells a story rather than merely being an image which has to be left to interpretation.

The bas relief on the southern side describes the coming ashore of the first Welsh colonisers in 1865, obviously bringing with them the most important export from Europe, the Bible.

It’s the bas relief on the north side I want to look at here.

It might be worth just giving a translation of the explanation of the images in the monument prepared and presented by the Puerto Madryn Municipality on the occasion of the unveiling of the monument in 2015 – the 150 anniversary of the arrival of the Welsh colonisers.

In describing the bronze bas relief on the northern facade of the monument it states:

‘Here we can see the Teluelche, sons of the land, receiving the colonisers, extending their hand in a gesture of welcome to the recently arrived, symbolising the meeting of cultures.’

Welsh Monument – Puerto Madryn, Argentina

Now I’m not questioning that this was the manner in which the Teluelche greeted the strangers from across the sea. Lots of cultures make it a point of honour to treat strangers with respect and kindness – unfortunately for the indigenous peoples of the Americas this was not part of the culture of those who arrived from the 16th century onwards.

I’m not also in a position to challenge what I was told by the curator of the small museum in the, now disused, railway station in Puerto Madryn that the Welsh colonisers argued, and were prepared to even take up arms to protect the interests of the Teluelche when they were threatened at one time by some of the more aggressive land grabbers from Britain with the assistance of the Argentinian state. What I want to ask is where are the ‘estancias’ – the large estates that make up the land grab of Argentinian and Chilean Patagonia – which are in under the control of the ‘sons of the land’?

Why is the city named after some tiny village in North Wales and not after the name the area would have been referred to by the people who had been passing through this region for generations before the Welsh ran away from Britain?

To remind readers of the situation as described by Chinua Achebe in relation to Africa – ‘when they came we had the land and they had the Bible, now we have the Bible and they have the land’. Is that any different with the Teluelche?

There’s also a bit of an oddity attached to the Welsh monument which has a tangential relationship to the Teluelche. On the hundredth anniversary of the arrival of the Welsh Protestants the Catholics in the area decided to thank them for bringing Christianity to ‘this land’. As can be seen in those images from the section on the church it was that Christianity that was important in destroying what might have remained of the indigenous religions and belief systems. And strange that the Catholics thank their most ancient of enemies in the Christian church – the Protestants.

Such believes, rituals and traditions are now seen as something quaint from a disappearing people but of having little relevance to contemporary life.

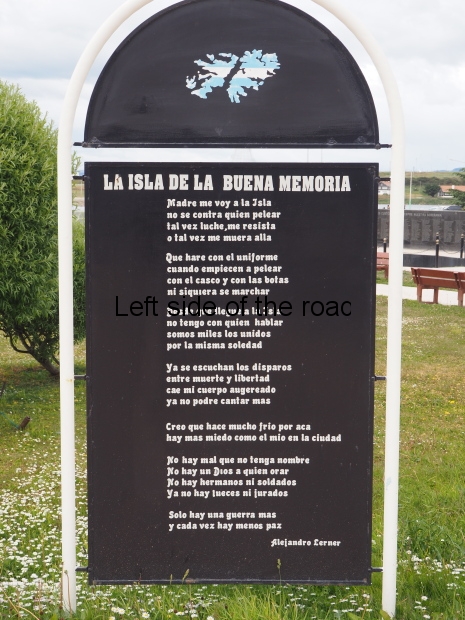

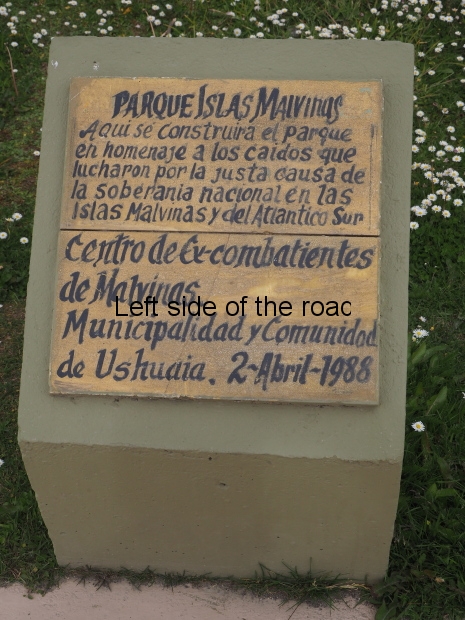

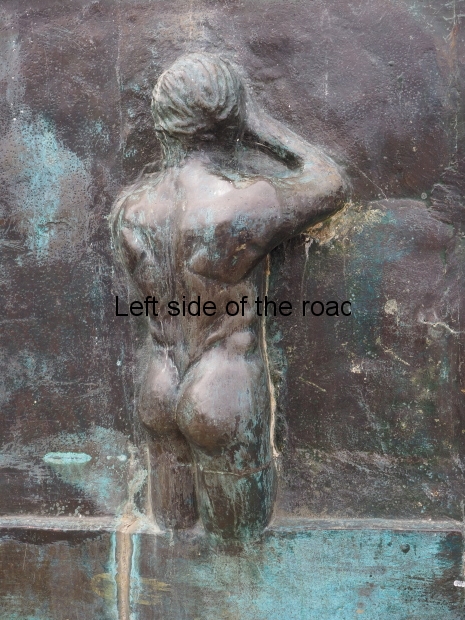

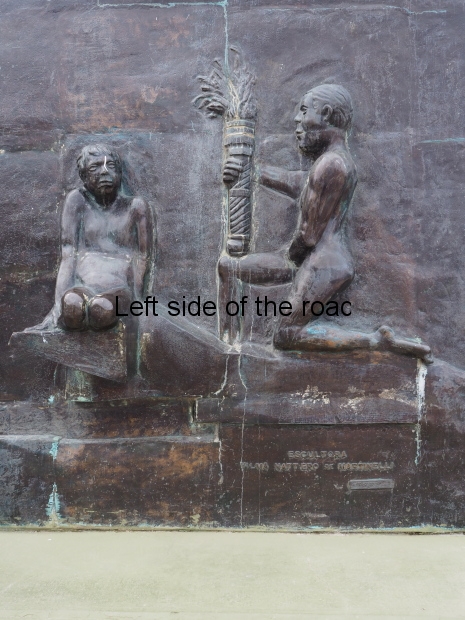

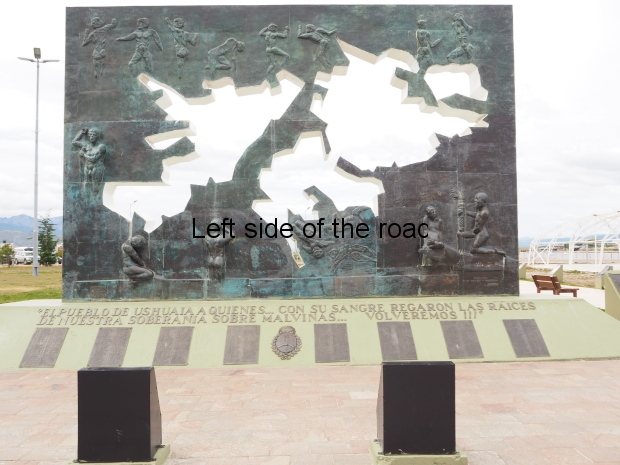

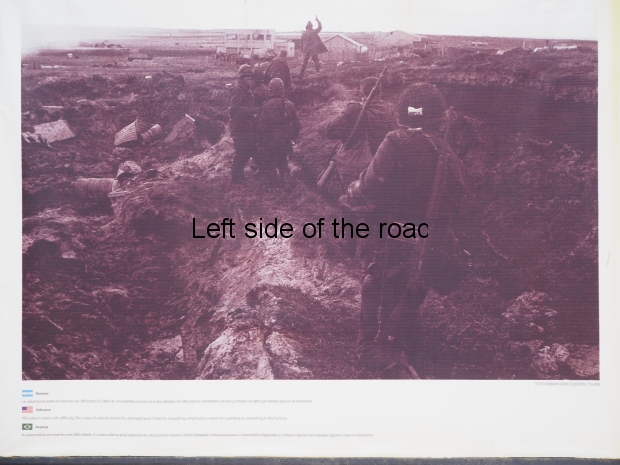

Monument to the Indigenous People – Ushuaia – Argentina

To the Indigenous People – Ushuaia

This is a small statue in the place that calls itself the ‘most southerly town in the world’. The smallness, in itself, might be making a comment. The Patagonians, when they first encountered Europeans in the 19th century were described as ‘giants’ and a number of excavations were made of grave sites looking for the large bones and a ‘scientific’ explanation of why they were so tall. This statue, of a male Selk’nam hunter kneeling, is probably half non-giant, life size.

Selk’nam group in traditional dress

I’m saying it’s a representation of a Selk’man as pictures I’ve seen of the tribe show the conical, fur cap as being part of the everyday dress of adult males. As with previous images he is not really wearing an animal skin coat but merely having it draped over his shoulders (in a totally impractical manner) which means that both his thighs, and the side of his upper torso, is exposed. In his hand he holds a bow – which seems to be accurate here as they were known to be good hunters with the bow and arrow.

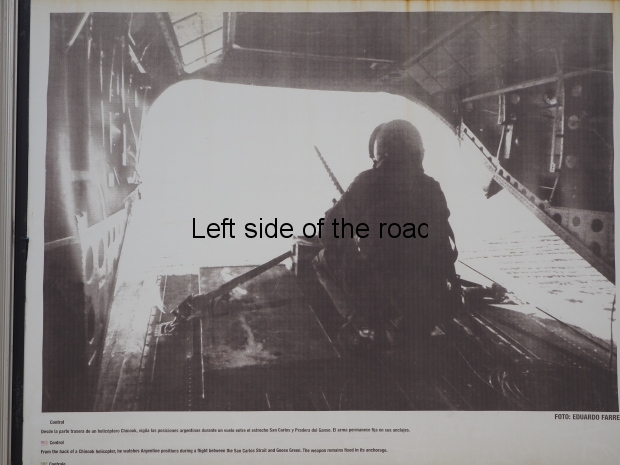

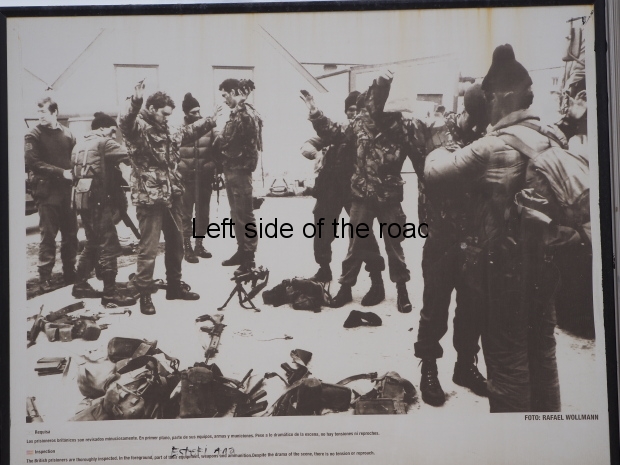

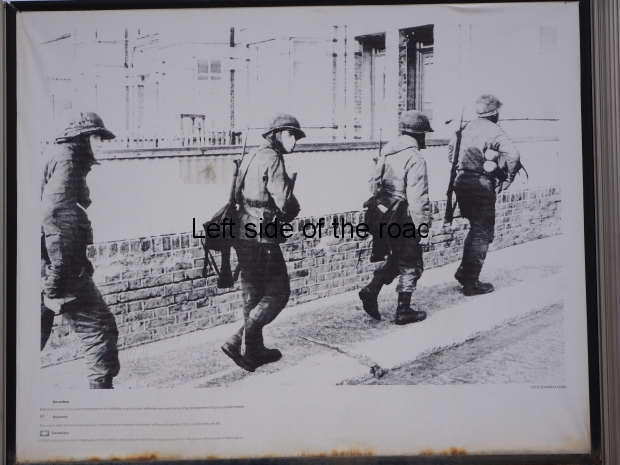

One of the problems that modern sculptors might be having in making a realistic representation of the Fuengüino people before their culture was overwhelmed by the stronger and more aggressive European culture is the use of that European culture to represent Fuengüino people.

European photographers who went to Tierra del Fuego wanted to give the impression they had ‘discovered’ a new race of people, these mysterious ‘giant Patagonians’. For that reason (and as we all know the camera never tells the truth) they would have local people pose in a manner that was stereotypical for ‘natives’. In a sense this was a return to the idea that pervaded the very few early years of the Spanish presence in South America in that they had found the natives living in perfect harmony with his environment, a paradise or heaven on earth.

This idea went well together with the idea of nakedness and so what were presented as candid pictures of everyday life are actually, in the main posed, in a manner that suited the photographer’s idea of the story he wanted to tell. The long exposure time of photography of the time also meant that the subjects would have to ‘freeze’ for the camera.

Seeing these collected together in a book of the whole ideology behind the collection of these images at the end of the 19th and beginning of the 20th century also shows the attitude of the Europeans to the local people. The power balance is shown in the often frightened, if not down right terrified, looks on the faces of the subjects – especially the children.

There are also examples where the photographer actually recorded his abuse of those who were weaker than himself. The two pictures taken by Martin Gusinde Hentschel – a Polish born missionary – show the extent to which the subjects had to suffer to get ‘the perfect image’.

Child abuse to satisfy European perversions

Child abuse to satisfy European perversions

It also seems to have been the fashion to have pictures of males just about to let loose an arrow in the countryside. The stories about the North American West and the ‘cowboys and indians’ had whetted the European thirst for peoples who lived by the use of old technology, whether it be to hunt or fight. However, those type of images in Tierra del Fuego were often of men who had adopted western culture and dress and were merely posing as natives, their ‘traditional’ dress over store bought trousers.

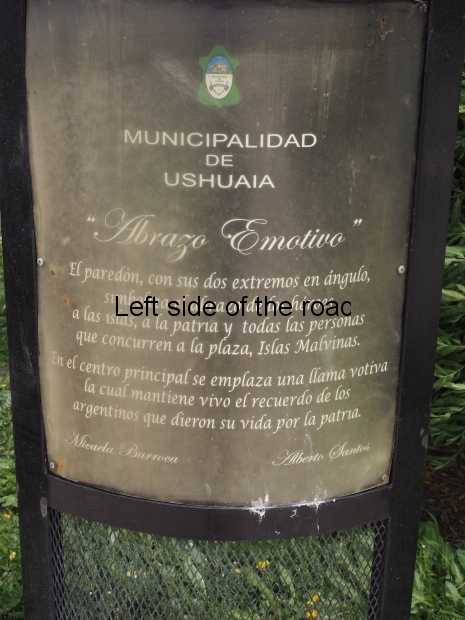

The monument is in the centre of town but slightly off the beaten track, in a small square just behind the tourist information office.

The accompanying plaque also tells a story.

To the Indigenous People – Ushuaia

This translates as:

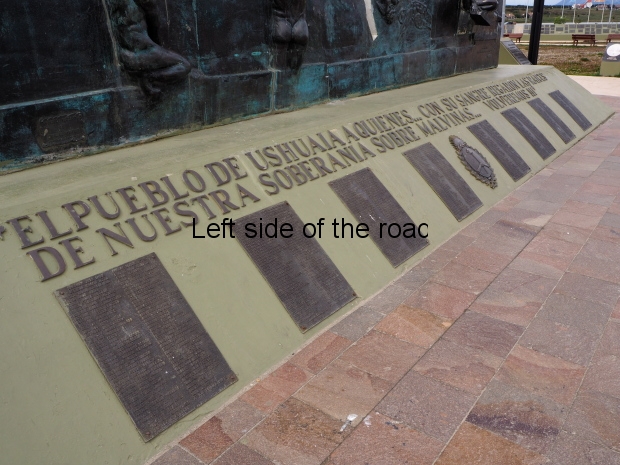

‘The Community of Ushuaia to the Indigenous People who created the origin of the city which today achieves its first hundredth anniversary. The Centenary Commission. 1884 – 12th October – 1984.’

Remember that 12th October used to be known as Columbus Day.

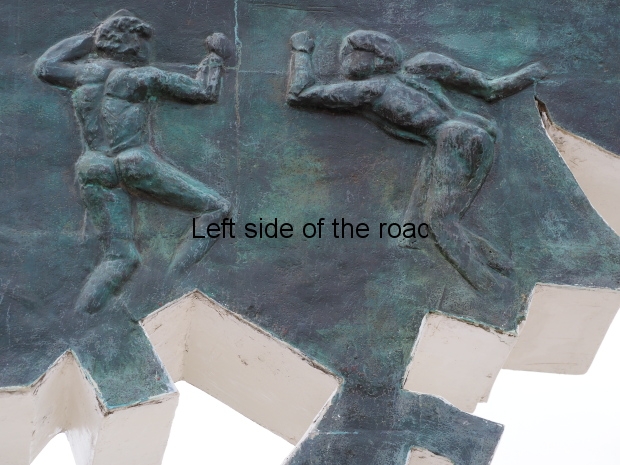

Pioneers and First Settlers Monument – Ushuaia – Argentina

I’ve not been very positive towards the monuments I’ve written about so far and I’m afraid nothing is really going to change with another, more recent and much larger monument that is also located in the centre of Ushuaia.

Pioneers and First-Settlers Monument – Ushuaia

This is in the form of a huge, concrete bird, an albatross, which has its wings unfolded so that it creates a semi circular protective space underneath. This is the only element that I think is original and creates a pleasing space. Unfortunately instead of just stopping here the sculptor decided to add to the perfection of the original shape.

But that’s not the worst thing about this monument. Taking into account the modest nature (to say the least) about Ushuaia’s recognition of the indigenous people one would have thought by the late 1990’s, when I believe this monument was unveiled, there would have been a review of the scant regard that Ushuaia had really paid to the people on whose land the city was built that a new monument would redress this balance.

But unfortunately this is just the opposite. This large, much more sophisticated, much more prominent and much more expensive monument is actually to commemorate the first (white) settlers of indigenous land and the so-called (white) ‘pioneers’ who followed in the late years of the 19th century.

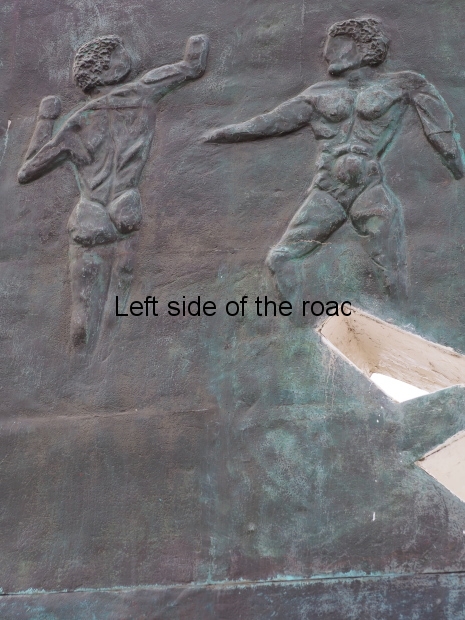

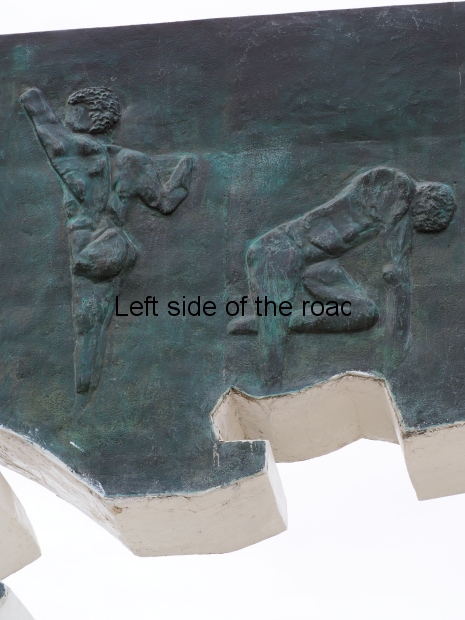

Not only does the city celebrate the invaders, the colonisers, the robbers and thieves of land that already had an owner it treats the indigenous people as extras in their own dispossession and then insults them by declaring that their presence in the images by the sculptor was to show how ‘the lighten [sic] fires symbolize the union among natives and First Settlers throughout history.’

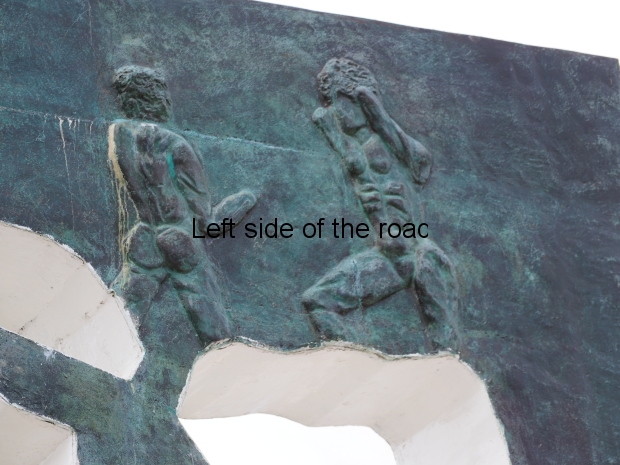

Inside this space we find a group of four people, three men and one woman, reclining against the wings and sitting around a large fire which separates the lone male from the other three. This fire has huge flames that rise up from the logs in the shape of the petals of an iris.

Some of them are dressed, some are not. Guess which (a ‘first settler’ or a ‘native’) is dressed. Wrong! It’s not the ‘first settlers’ but the two ‘natives’. First settlers come out of the womb already dressed and never take their clothes off – especially the religious ones.

Pioneers and First-settlers Monument – Ushuaia

So yet again there’s this distinction between the primitive and the sophisticated.

But it gets worse when we look at the decoration on the external part of the sculpture. As the indigenous people are mere bit players in this scenario, apart from their nakedness in front of the fire, they only appear once more, this time to accentuate their backwardness.

On the left hand side at the back we see examples of the masks used in their rituals (primitive), the simple huts in which they lived (primitive) and their use of canoes as a form of transport and for fishing (primitive).

Pioneers and First-settlers Monument – Ushuaia

Right next to these images, as we move right, are examples of what the ‘first settlers and pioneers’ brought with them. There’s a steam ship, a steam train (although no reference to the fact that the ancestors of these same ‘pioneers’ have allowed the once extensive railway network in the country to decay and rot into insignificance) and part of a large two storey building (the prison that was built in the early days of the city’s history – isn’t it interesting that a symbol of ‘progress’ is a prison building?) together with a European marching forward in a positive manner.

Pioneers and First-settlers Monument – Ushuaia

Next we have two males using a two handed saw to cut a log – representing the logging industry that was set up very soon as the town grew. This industry would have forced the Selk’nam and Yánama to fill in for shortages of labour.

This is followed by a carpenter in the process of constructing one of the typical houses that were everywhere in Ushuaia until the latest round of destruction which has replaced those typical buildings by featureless and souless modern concrete constructions – so even the ‘first settler’ and ‘pioneer’ culture gets trashed by the juggernaut of capitalist development.

Next is an image of a mother raising her baby high above her head as she plays with the child (natives’, presumably, didn’t play with their children) right next to an image of the Salesian Cathedral to be found on the main street of Ushuaia.

Finally we have the image of a man digging a hole in preparation for the planting of the small tree a child is holding.

So all the industriousness of the Europeans have created the city of Ushuaia. Of what the indigenous people had created over the generations there remains nothing, as their creations, their homes, their means of transport came from nature and returned to nature. Their culture is now only fit to be represented in museums, used as decoration on hostel walls or as artefacts to be sold in souvenir shops.

Pioneers and First Settlers Monument – Ushuaia

Just in front of the ‘camp fire’ is a roundel with a compass in the middle and radiating out to the edge of the circle on the lines is a list of those nationalities who had contributed to the construction of the city and its economy. Listed are: Poles, Croats, Israelis, Chileans, Greeks, Lebanese, French, Germans, English, Solvenes, Spanish, Yugoslavs, Argentinians, Italians – and as a sop to the past Selk’nam and Yámana.

Strangely the descendants of the ‘first settlers’ were asked how they wanted the monument to be called and even had the letters they sent in response to that request reproduced and put on display. When did they ever ask the indigenous people – or the few surviving descendants – how they wanted to be remembered?

There’s even a list of the first 50 settler families in the area, a plaque paying ‘homage’ to them having been placed on the wall to the back of the monument.

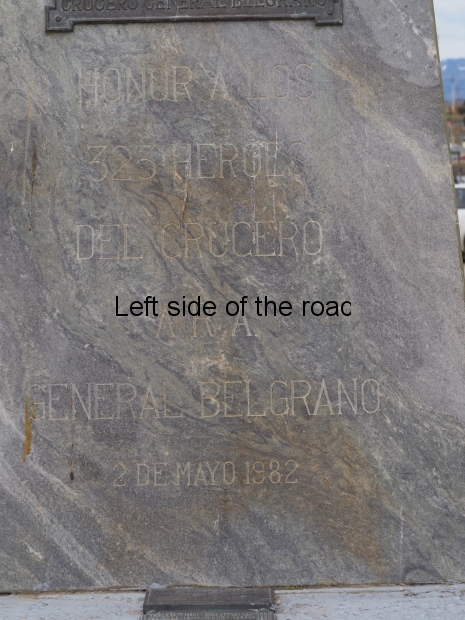

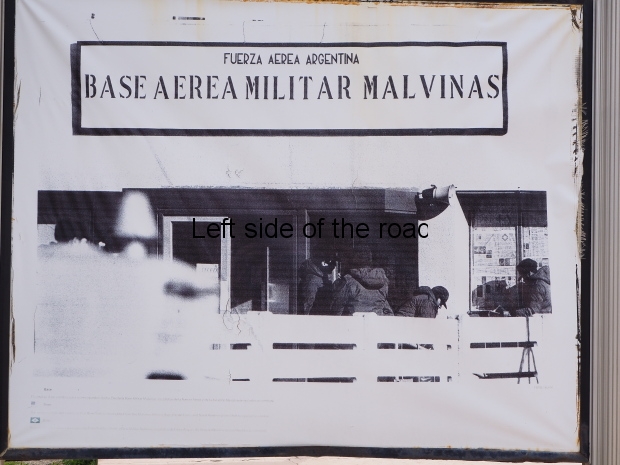

Ushuaia calls itself the ‘capital of the Malvinas’ and declares that ‘the Malvinas are and will be Argentina’s’ but it doesn’t pay any respect to any claims that the indigenous people might have on the site of the city.

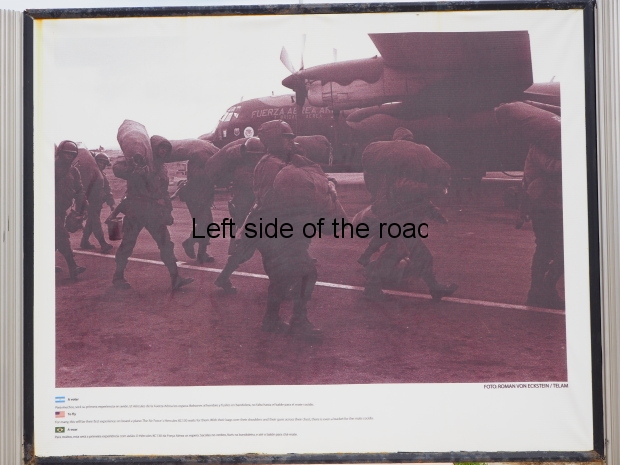

The indigenous people in the photographic record

As it is almost certain that any images of the pre-colonial people who have been or are to be turned into a work of art come from the photographic record made by European photographers at the end of the 19th and the beginning of the 20th centuries it might be worth while discussing how using such material colours (and quite possibly) distorts the true representation of life before the invasion.

As stated before photographers were out to get ‘the’ image that would make their reputation and, hopefully (for them) their fortune – no different from the paparazzi now. This meant that as has always been the case they would have to produce images that the market wanted. By the end of the 19th century there were few civilisations that had not been documented in some way and however badly and inaccurately they may have been represented were ‘known’ in Europe. The encounter with Patagonians must have been a godsend for publicists.

But Europe had developed an idea, which had originated first with the invasion of the Americas in the 16th century and later with Africa and Australia, that all these primitive peoples behaved in a similar manner. They all walked around naked, they had no culture as was understood in Europe and had little technology in a world where the industrial revolution that had begun in the 18th century was still producing marvel after marvel.

To have presented the Patagonians as being any different would not have been accepted by societies which had preconceived (and it has to be said deep rooted racist) ideas of what other people were. If they are not us then they are different and if different they must be inferior.

The church also had a role in this, by the end of the 19th century the Protestant as well as the Catholic brand of Christianity.

Their mission (and the reason they sent out missionaries) was to ‘bring the word of God’ to those who were following a misguided road. Why God had to be brought to people who had been created by that very same God is a mystery to me. But then reason and rational thinking has never been behind religious proselytisation.

The church also had to show progress in their mission and the most obvious way that could be done was by changing how the native people’s looked – basically by getting them to adopt a western style of dress. To show that radical change in an easy way it was beneficial to their idea to show that the natives were so unsophisticated that they didn’t have any clothes at all and this is one of the expectations that pushed the production of naked images of men, women and children.

There could also be argued that there was a prurient reason for such images – European society had become so anal at the end of the 19th century that naked images of whites were rare (although available) and would never be displayed in public but such images of naked, dark skinned, foreign and distant peoples was totally acceptable.

Then there was always the question of power. Once the colonisers arrived they started to come in a flood. If the first few had been welcomed (as is shown in the Puerto Madryn Welsh monument) then there would have come a time when the numbers started to be unacceptable – especially as they were arriving with the understanding that the land was empty and there for the taking. This had happened in North America and Australia, why should Patagonia be any different?

That would necessarily have led to conflict, fights and injuries and deaths. But the battle would have been far from equal and massacres were far from being unknown. One that became famous due to the fact that it was documented by a series of photographs was that by a gold-prospecting Rumanian by the name of Popper.

As has always been the case one of the justifications for taking the land from another ‘tribe’ is to brand that tribe as being savage, uncultured and needing to be educated of the true light. If they refuse then eradication is the only option.

With this background, by the 1910s and 1920s the Patagonian people, of whatever tribe, were defeated, dejected and miserable. Their hunter gatherer way of life had been destroyed by the seizure and privatisation of the land, their culture and religion had been branded as heathen and had been forced to adopt the Christian faith, they had been forced to wear ragged ‘European’ clothing in place of their warm and comfortable guanaco furs, they had been forced into a situation somewhere between slavery and feudalism and having to adapt to a money economy. The overwhelming number of images I have seen taken in that 50 or so year period show a humiliated, defeated and thoroughly miserable race of people with little hope for the future and a past that had been destroyed forever.

A number of pictures show how the Salesians, the so-called saviours of the indigenous people, were far from reluctant to make use of this new and virtually free workforce with members of the various tribes being forced to work in small factories and workshops in the Salesian missions.

The situation there appears to be as abysmal as those experienced by British workers in one of the most dire periods of conditions of the working class in mid-19th century Manchester. Unlike the British working class who were eventually able to organise themselves and fight for their rights the Patagonian people just disappeared.

Note how in all these pictures a priest or a nun stands guard, as overseer, as boss, as ocontroller. I don’t use the word ‘evil’ on many occasions (it’s too value laden) but until I can think of a more appropriate word I’ll stress how this evil presence, the Devil’s representatives on earth, are a symbol of the pain and suffering of these defeated people. I don’t like using the word ‘defeated’ but I can’t find any evidence that the Fuenguinos were ever able to recover from this treatment.

Fuenguinos working in Salesian Mission

Fuenguinos working in Salesian Mission

Fuenguinos working in Salesian Mission

Fuenguinos working in Salesian Mission

Fuenguinos working in Salesian Mission

One thing that did stand out in the pictures I have seen that were taken at the time of the transfer of power from the Selk’nam and Yámana to the white colonisers is those taken by the Salesian priest Alberto María De Agostini Antoniotti. His pictures are the only ones where the subjects seem to be happy in having their picture taken and not being coerced into being photographic models. Not being a fan of priests of whatever species he obviously had a different relationship to the local people (in the 1920s) than did the majority of the parasitic creatures which had been forcing subjects to sit for pictures which they either resented having to do or were photographed without any choice – and never would any of these people have seen their own images.

Smiling Girl – De Agostini

Statue of De Agostini and Pa-Chiek Kon Ona in Puerto Natales, Chile

Right next to the waterfront in the Chilean town of Puerto Natales is a statue commemorating the Salesian priest Alberto De Agostini and he is depicted shaking hands with one of the elders of one of the Patagonian tribes, Pa-Chiek Kon Ona with a symbol of a bow and arrow carved below his name.

Alberto de Agostin – Puerto Natales

This is a simple, almost cartoon like, sculpture of two people meeting and its simplicity makes it quite charming in a way. Again, whether this is a true representation of what actually happened is debatable but it is the first sculpture I’ve seen where the idea of an encounter rather than an invasion is being depicted.

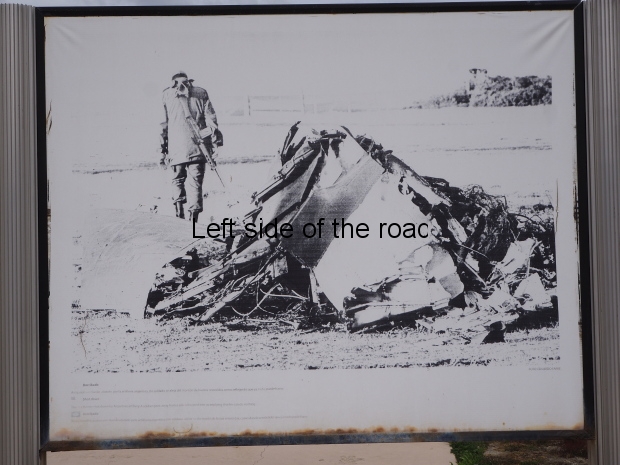

Monument to General Julio A Roca – Rio Gallegos – Argentina

Roca Statue Rio Gallegos

This idea of the marginalisation of the indigenous people in public monuments doesn’t just relate to events at the end of the 19th and the beginning of the 20th centuries. This idea that they were a group of savages that had to be either converted to Christianity or destroyed was there from the time of the ‘liberation’ wars against the Spanish.

In the coastal city of Rio Gallegos in Argentina is a statue to one of the generals of the liberation war, Julio Roca. This ‘celebrates’ a meeting between him and a Chilean counter-part, Fernando Errazuriz in 1831.

(Ironically this posits the idea of the eternal friendship between the two countries. However when that friendship was put to the test in 1982, at the time of the war over the Malvinas, the Chileans – under Pinochet – showed themselves quite capable of stabbing a neighbouring country in the back by supporting the British in place of the Argentinians, even allowing the British armed forces to operate on Chilean territory as well as providing vital intelligence of Argentinian troop movements.)

But when it comes to the approach to the people who were here before the Spanish we have to look at the lower of the two panels that accompany Roca’s statue.

Here we have Roca and his aides, on horseback on the right. Roca has his right arm outstretched and his forefinger is pointing threateningly at a small group of indigenous people who are on the extreme left of the panels. Most of them are standing up and huddled together – aiming to get some comfort from the proximity with their kind. One of their member is crouched down, his head bowed and his arms covering his eyes. As is normal in virtually all depictions of the indigenous people they are half naked. The reason for this scene? The priest who stands between the two groups.

He has his right arm raised and in his hand is a crucifix which is radiating the light of the Lord. Even though the settler descendants of the Spanish were fighting against the dominance of the Spanish state in the affairs of the Latin American continent they were in no way fighting against the hold the Catholic church had on all the peoples of those lands.

The indigenous people are afraid of the power of this religion and the one crouched down is displaying his shame at not accepting the true religion.

And Roca is saying, with the threat of arms, that if the heathens do not accept the true religion the full force of the army will be used to force them to do so. ‘Submit or die’ is what he is indicating with that simple gesture of the outstretched finger.

So it ever was.

More on Argentina

Previous Next