Rosanes – a military airfield during the Spanish Civil War

Memorial Democratic, a programme to spread information about the history of the Spanish Civil War, tells the story of the small Republican airfield of Rosanes, just outside La Garriga in the hills just to the north of Barcelona, Catalonia.

I’ve said that it’s possible to walk in this part of Catalonia during the month of August but I would still not recommend doing what I did a few days ago which was to visit the site of one of the Republican airfields during the Spanish Civil War at 3 o’clock in the afternoon. Being now farm land there is absolutely no respite from the sun as Catalonia, as well as much of the rest of Spain, is going through a heat wave.

But for anyone interested in that defining period of European history a visit is worthwhile.

Rosanes is the name of a large farm a couple of kilometres to the south of La Garriga, a town which grew up at the end of the 19th and the beginning of the 20th centuries as a favoured place for the Barcelona rich to escape the extreme heat of the Mediterranean summer.

There’s not a great deal left of the complex that existed for a short, but intense, period during 1937-38 but there’s enough to get a feel for what it was like when the Republican air force tried to stand up against the might of the German Luftwaffe and the Italian Regia Aeronautica. But this quiet place, now returned to use as farm land and a small golf course, played a significant part in some of the campaigns of the Civil War as well as playing its part in the defence of Barcelona, only just over 30 kilometres away.

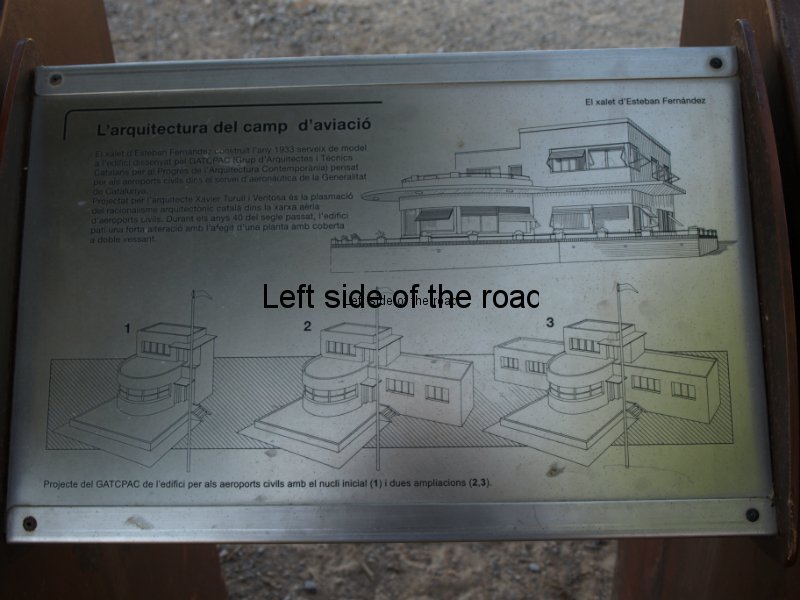

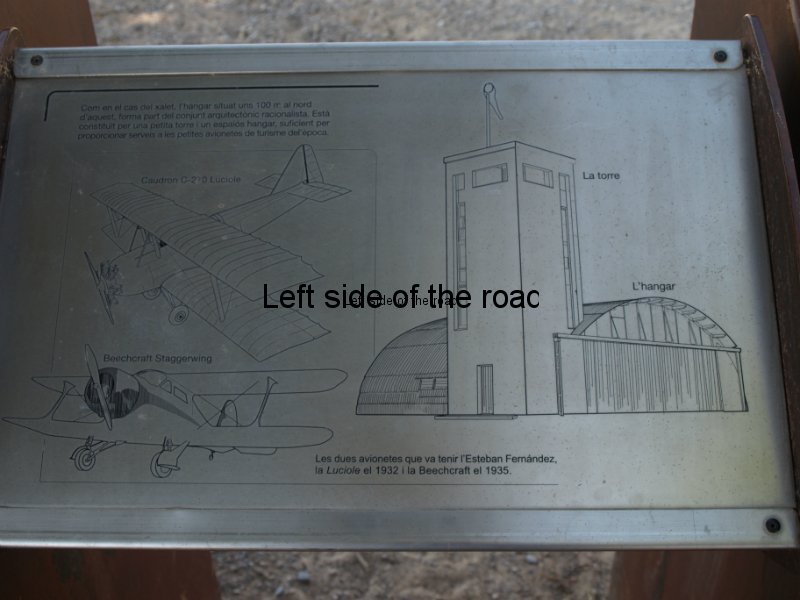

The reason for the airfield being there was really one of chance. A rich Argentinian businessman, with a passion for flying, constructed a landing strip, together with a hangar, a control tower and a house which were all requisitioned by the Republic when hostilities began.

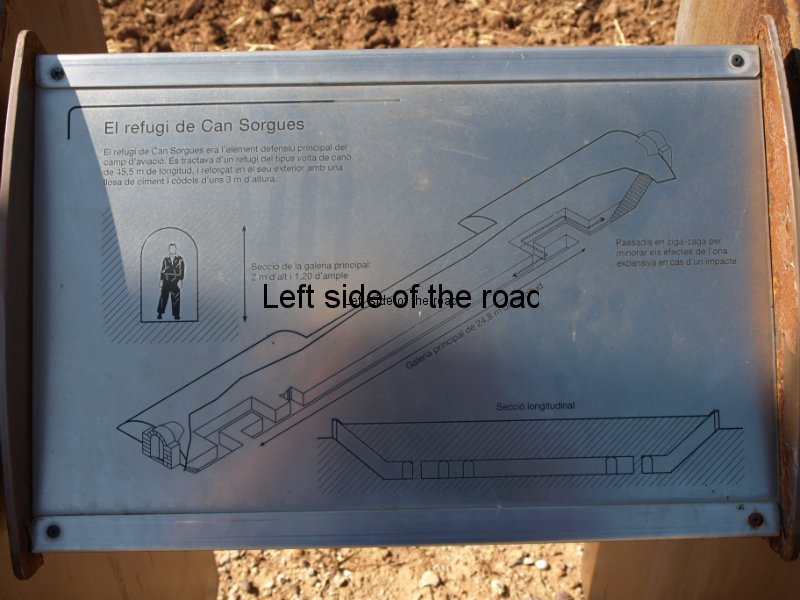

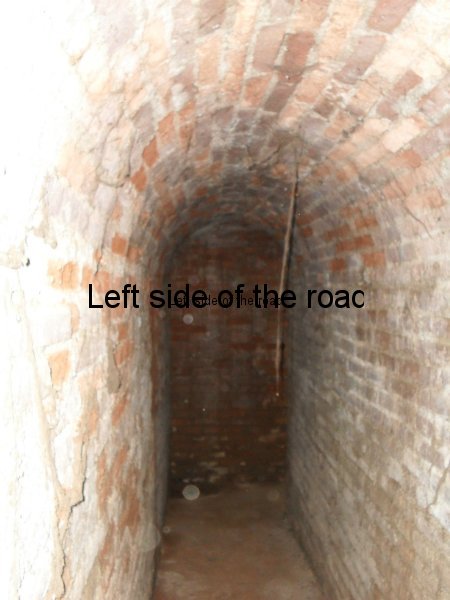

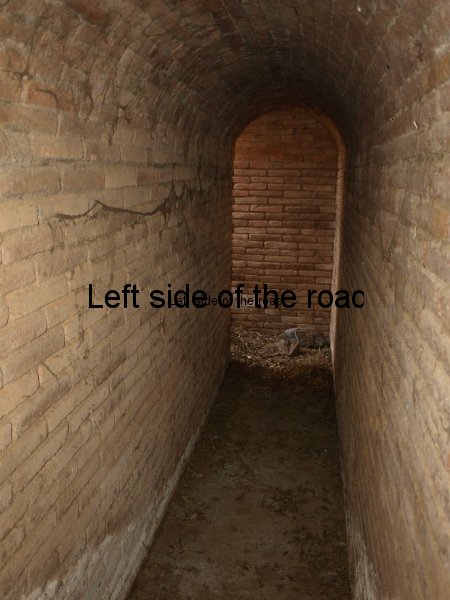

As the place developed from a private civilian airfield to a military centre all the operational and accommodation facilities were spread over a large area to avoid concentration of resources in a small place which would have had disastrous consequences if there had been a lucky strike by the fascist bombers. All its working life the airfield was under threat of aerial bombardment and three, out of a total of 7, of the still existing structures are air raid shelters.

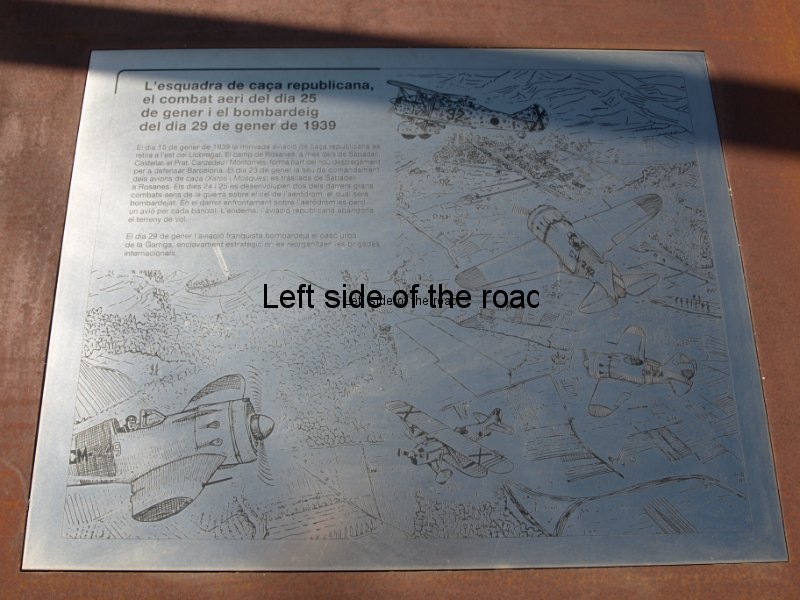

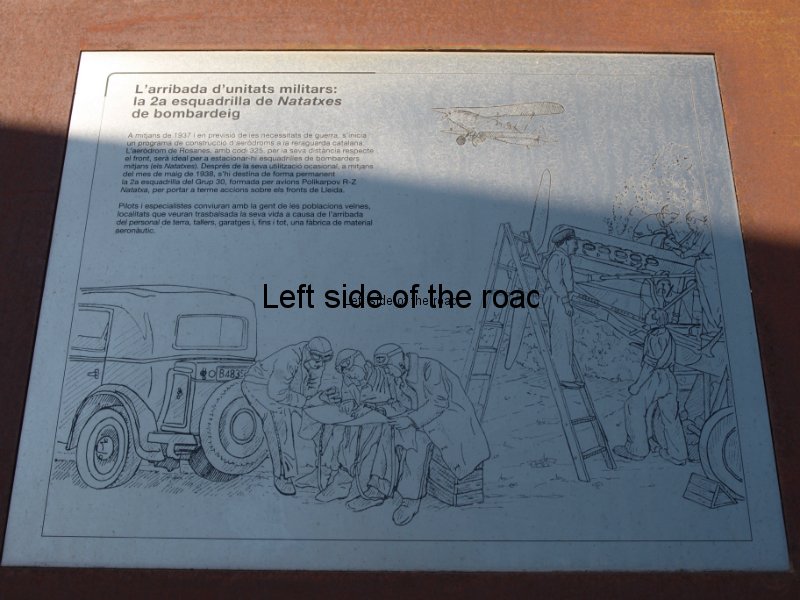

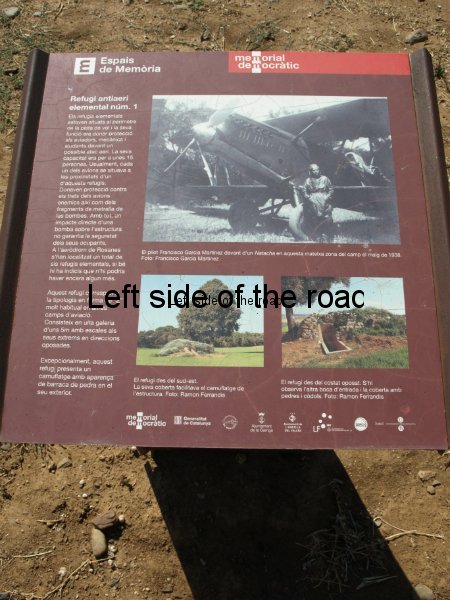

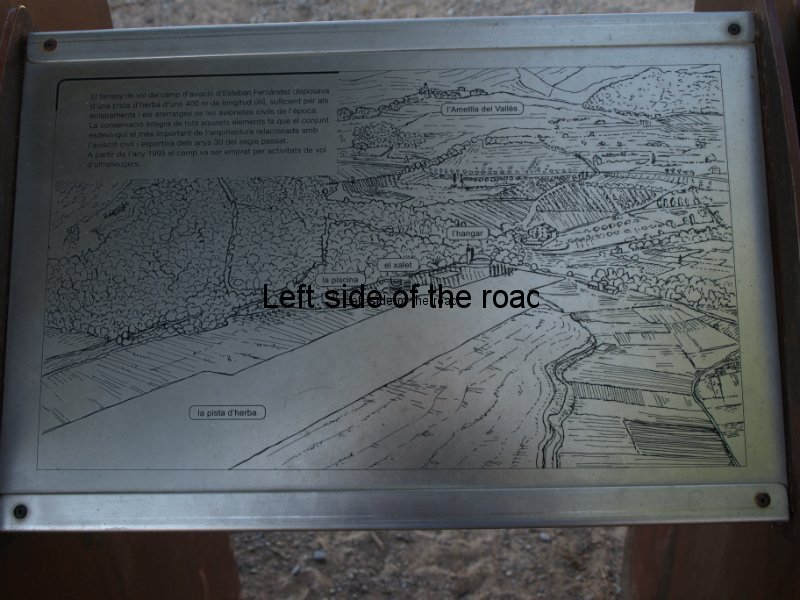

At two locations in the area there are information points which provide a fairly comprehensive introduction to the activities that took place in those years. With sketches etched into stainless steel any visitor can come away knowing a lot more about what the place looked like and how the airfield functioned as an efficient war machine.

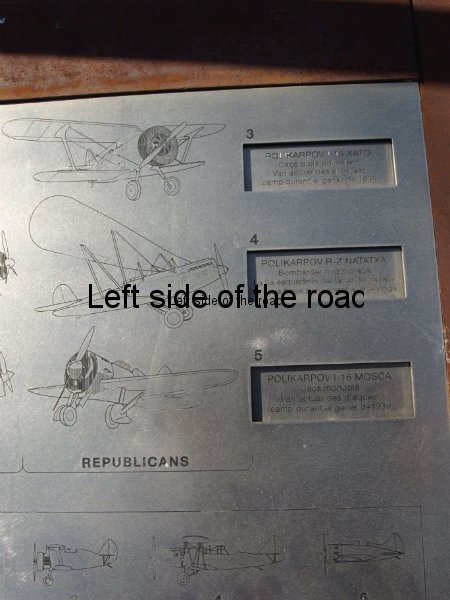

This includes a description of the aircraft that the Republicans used at Rosanes. These were all Polikarpov aircraft provided by the Soviet Union, the most famous of these being the Natasha, a light bomber and the plane around which the aerodrome was built. It was after this squadron was virtually wiped out on returning from a raid on the 24th December 1938, due to a mistake and consequent lack of fighter support, that Rosanes began to lose its importance.

The information boards also give an indication of the position of Rosanes in the evolution of the Republican defensive front. Much of what the Republican forces built was in response to a concerted attack that had been planned over many months. What has to be remembered is that it was the fascists who were the rebels, rising up against the legitimate government of the Second Republic, who had planned their attack with the overwhelming support of the war machines of Germany and Italy. Taking into account this imbalance of forces it’s surprising that Spain was able to hold out for three years. Poland and France didn’t last a fraction of that time.

The three principal buildings of the pre-war complex still exist but can only normally be seen from afar, as they are now back in private hands. These are the buildings constructed for the Argentinian businessman and are the hangar, the control tower and the house built close by which became a command centre.

The other remaining structures are the air raid shelters. The two smaller ones have gates across the entrances but a little bit of limbo dancing will mean that you can get a view of the interior and this is useful to get an idea of how small they were but still providing the necessary protection against attack.

The third shelter, by far the largest as it was constructed close to the biggest concentration of personnel, can only be seen on one of the organised visits. This is next to Can Sorgues, where there are also the remains of the camp dinning room as well as a sentry box, looking in a very good condition for something that is supposed to be from the 1930s.

But apart from the structures that can be seen/visited perhaps the main thing to be gained from a visit to Rosanes is the realisation of how small things were in those days, how makeshift war was in the mid 1930s and how hit and miss the whole matter of warfare was at that time. Matters moved drastically during the ‘big’ war of 1939-45 (in which Spain did not take part) and so different from the high-tech warfare of today in Iraq, Afghanistan and …. Iran?

A guided tour of Rosanes takes place the second Sunday of every month, meeting at the Rosanes farmhouse at 11.00. In July and August, when it’s much hotter, the visit takes place at 18.00, the one in August being on bicycles. It costs €5. For more information call 93 113 70 31, or email info@visitlagarriga.cat. For some pictures of the time go to www.aviacioiguerra.cat, although this is only in Catalan.

Rosanes Airfield Information Leaflet in pdf format

For more information on Memoria Democratic see: