The Madonna Crushing the Devil

I hadn’t been in the Caribbean for more than an hour before I was introduced to the importance of religion, more especially Christianity, on the small islands that make up the Windward islands in the West Indies.

The short (and expensive) taxi ride from Piarco airport in Port of Spain, Trinidad, to the OK but severely overpriced hotel close to the airport was one accompanied by religious music. It was a Sunday and though over the top, in a way, understandable. This was the same for the programmes on the tele in the hotel room. Not a great choice of channels but every other one was of some preacher of some sect ‘selling’ their wares.

But the relevance of religion to Caribbean societies was to be reinforced as I travelled to some of the other islands in the archipelago.

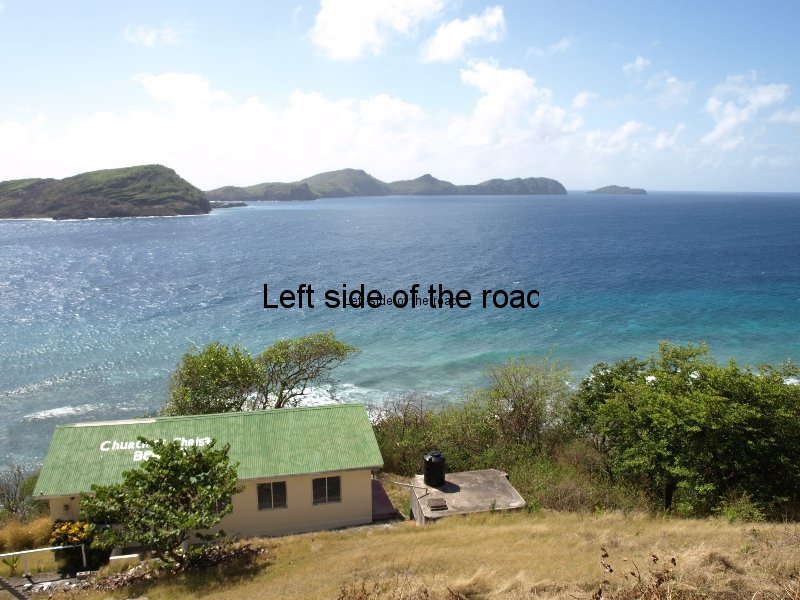

In the village of La Pompe, on the Atlantic coast of the island of Bequia, there is a small Ephesian Tabernacle, up some steep steps off the main road in the centre of the village. What makes the location interesting is that at the bottom of the steps, right beside the main road, is the local rum shack and village store. Whilst the righteous are praising god up the steps the damned are knocking back quarter bottles of the local 84% proof double strength white rum.

Ephesian Tabernacle, La Pompe, Bequia

On a Sunday this little, one room, church hall has a service from 10.00 until 13.00 and all the time, with the assistance of amplification, not only the faithful are treated to sermons – whose sole basis seems to be of the imminence of hell and damnation – but so are the rest of the village and anyone who passes by. When I first went passed the rum shack I didn’t realise the chapel was further up the steps (it just looked like a normal house) and thought, with a sense of shock, that the rum shack doubled as a church on a Sunday.

The churches are also one of the few places where you are able to observe the colonial history of the different islands. For much of the 17th and 18th centuries the islands were in dispute between the French and the British. This colonial history is represented by the architecture of the churches and cathedrals as well as the division between the Catholics and the Protestants.

Many of the Catholic cathedrals were built by the French and this can be seen in their architectural style as well as the interior decoration, including memorials, in French, to the rich and powerful at the time of that country’s dominance. This has produced some really quirky, not to say bizarre, structures, such as the Catholic Cathedral in Kingstown, St Vincent. This seems to encompass virtually every architectural style known at the time of its construction and seems more fitting for a Disney theme park than a small port town in the Caribbean.

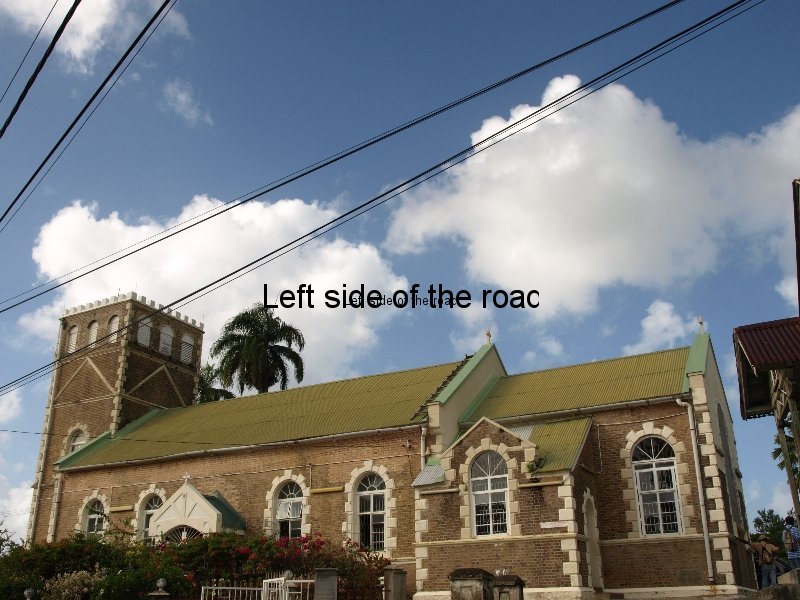

Kingstown, St Vincent, Catholic Cathedral

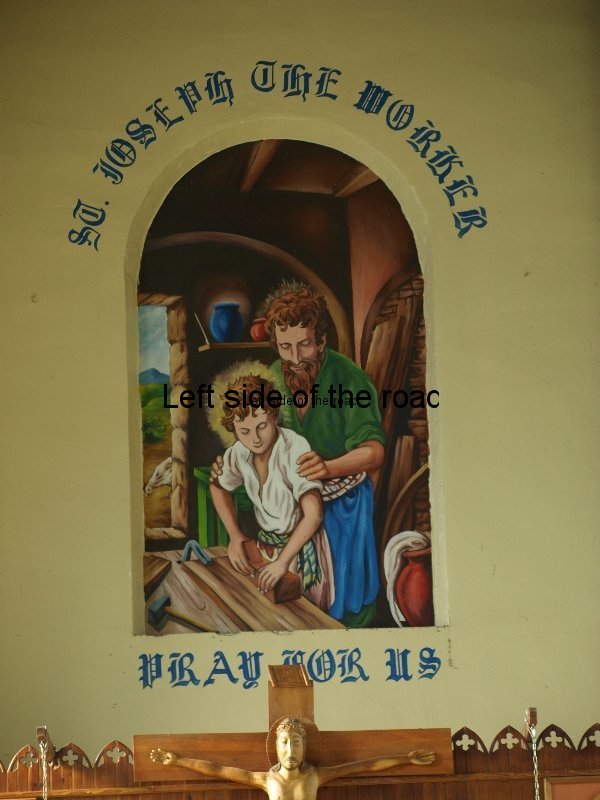

The other significant French influenced Catholic Cathedral I was able to visit was that in Castries, the capital town of the island of St Lucia. As with all the older religious buildings on the islands there is the architectural influence from Europe but built with the limitations set by the materials to hand in the islands. As in other colonial countries throughout the world the local indigenous artists create images that are a fusion of their own, pre-colonial, culture with that of the foreign, European invader.

What I always find interesting in such situations is how the black indigenous culture adapts, some might even say subvert, the predominantly white Christian iconography. Since the Renaissance there’s been a reversal in the trend that had developed over the early centuries of Christian dominance in Europe. Romanesque images of Christ depict a dark-skinned, dark-haired male, after all he was supposed to be a Jew living in Palestine. That morphed until by the 20th century Christ became a blond, blue-eyed Aryan beloved by the Nazis.

A ‘fight-back’, if you like, can be seen in the relatively new stained glass window in Castries Cathedral. Here both the Mary and Christ figures are definitely of a darker skin. Also in that cathedral the crib that had been constructed for Christmas (and which was still there at the end of January, as the imagery remains until the end of January or early February in some parts of the world) has a black child’s doll as the baby Jesus figure, which is of a hugely disproportionate size to the adult figures surrounding it. And in the background there’s a carved wooded figure of an indigenous female figure, again disproportionate in its dimensions.

Castries Nativity Crib, 2012

The church at Gros Islet, the local village next to the huge and full of very, very expensive yachting marina of Rodney Bay is another good example of the influence of Christianity on the islands. Just by chance, on the two occasions I visited the place there was a funeral taking place in the big, town centre church. On both occasions the church was full with people in their ‘Sunday Best.’ Although the predominant influence in the interior decoration was white European a relatively new, life-size, wooden crucifix over the altar had very definite African influences.

Crucifix Gros Islet Church, St Lucia

Whilst in the Catholic churches it was very easy to see the roots in the European design of the time the Anglican churches, built under British influence, are very different. They are as austere as the Catholic are over the top. This is particularly evident in Kingstown, St Vincent, where the two cathedrals are right next to each other, seemingly in competition to define their particular faith through architecture.

Other Anglican churches wouldn’t be out of place in the English countryside. They haven’t allowed the indigenous cultures to influence their design in any way and the British naval officers and their wives would have had no culture shock in going to a Sunday service if they went to a church in Castries or Canterbury.

Castreis Anglican Church, St Lucia