More on the Maya

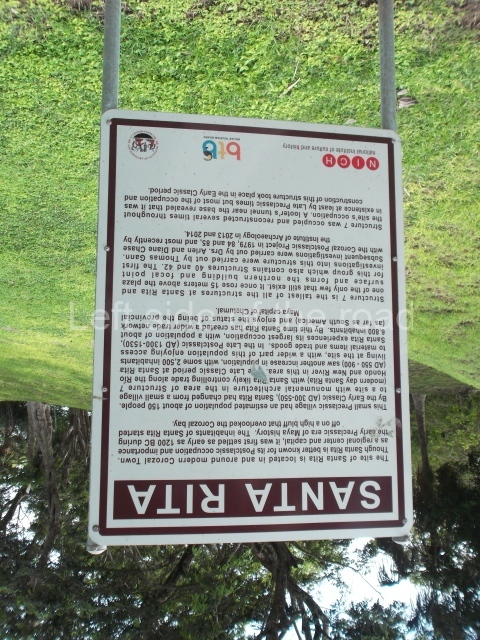

Santa Rita Corozal – Belize

Location

Situated in a strategic position on a major trading route along the Caribbean coast and close to the Hondo and New rivers, Santa Rita enjoyed easy connections with inland sites such as Lamanai, La Milpa and other cities in Peten. Its main products were achiote, honey, vanilla and a variety of fish and molluscs, and it is said to have been particularly famous for the quality of its cacao. Objects imported from distant places have also been found, such as turquoise (which could have come from Peru or the south-west of the United States), Plumbate ceramics (Guatemala), objects of copper and gold of varying provenances and gold ear ornaments possibly of Mexican origin (central Mexico). All of this reinforces the hypothesis that Santa Rita was an important port of trade. Much of the site has been destroyed by the development of the present-day Corozal; its structures have been dismantled and many of the stones from the old buildings have been incorporated into streets, plinths and modern constructions. Originally, the site extended much further to the north and south-west of Corozal. Nowadays, it is situated on the outskirts of the city, on the edge of the Northern Highway leading from Belize City to the Mexican border. It can be reached by car or public transport. From Corozal, head northwest along the highway and after a kilometre or so you will see a statue where the road veers to the right. Take the next turn left and the entrance to Structure 7 is a few metres beyond Hennessy Restaurant.

History of the explorations

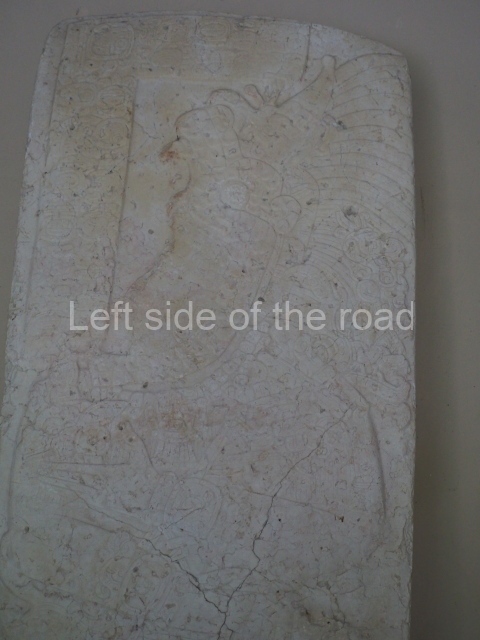

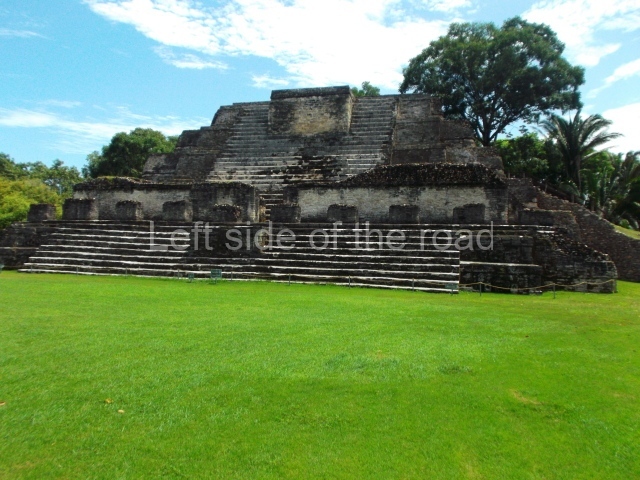

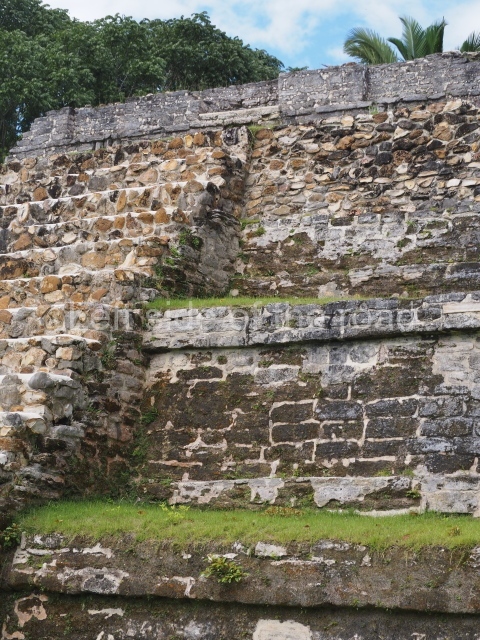

At the beginning of the 20th century, Thomas Gann made a rough map of the site, conducted several excavations and discovered a Mixteca-style (from Oaxaca) mural in Structure 1. Nowadays nothing of this mural remains and Gann was unable to complete his record as not long after its discovery it was destroyed by the local inhabitants. However, Gann’s drawings and detailed record have survived. The mural corresponds to the Postclassic period and has been dated to between AD 1350 and 1500. Similar murals were found in Structure 16 at Tulum (Quintana Roo, Mexico). In 1979 Structure 1 was bulldozed. At the beginning of the 1970s, Ernestene Green, Duncan C. Pring and Raymond V. Sidrys conducted minor excavations. Subsequently, between 1979 and 1985, Diane and Arlen Chase from the University of Central Florida led the Corozal Postclassic Project, which involved the excavation and consolidation of Structure 7. What remains of the site today, the central part, is situated inside an archaeological reserve.

Pre-Hispanic history

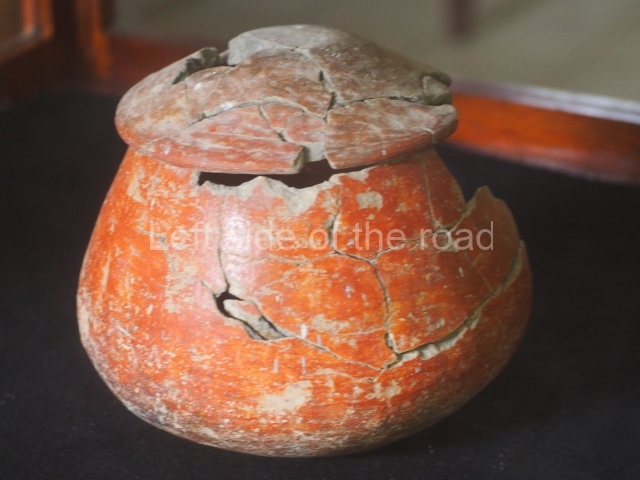

Although Santa Rita is best known for its importance during the Postclassic period, when the site experienced its heyday, the earliest settlers arrived around 1000 BC. Ceramics from the Swasey phase – the oldest in the Mayan lowlands – have been found. Santa Rita boasts one of the longest sequences of occupation in Belize, commencing in the Middle Preclassic and culminating in the Postclassic and even the period of contact with the Spaniards. It was abandoned towards the end of the 16th century. The archaeological area of Santa Rita is widely believed to have been the famous city of Chetumal (Chactemal province), which is mentioned in sources from the 16th century and formed part of the League of Mayapan. When the Spaniards arrived it was an important port. Its strategic position appealed to the conquerors, who decided to establish a base there. In 1531 Francisco Montejo sent Alonso Davila to take control of the site, but on his arrival he discovered the city to have been abandoned. Davila established his base and called it Villa Real. The supposed abandonment of Santa Rita was in fact part of a Maya strategy, and the original occupants launched a counter-attack and recovered Chetumal. And then the strangest thing occurred: Nachancan, the governor of the city, had a Spanish son-in-law, Gonzalo Guerrero, the survivor of a shipwreck off the south coast of Jamaica in 1511. Guerrero is regarded as the ‘father of the mestizos’ because he married a Maya woman, had children with her and adopted the local customs. It is said that he eventually became Nachancan’s military advisor and participated in various battles against the Spanish. Eighteen months later, the Maya forced the Spanish to retreat south, to Honduras.

Site description

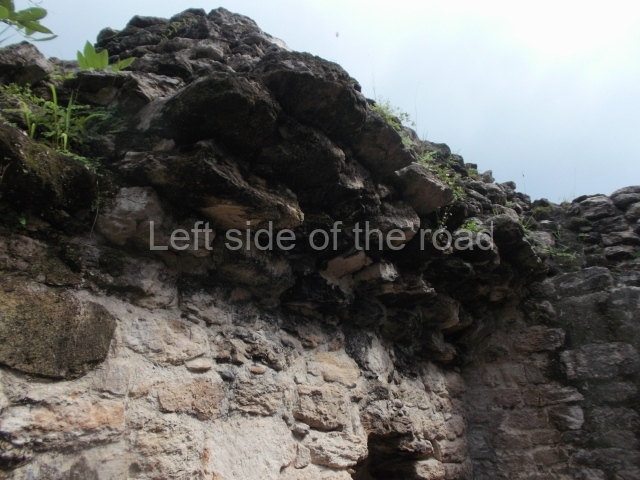

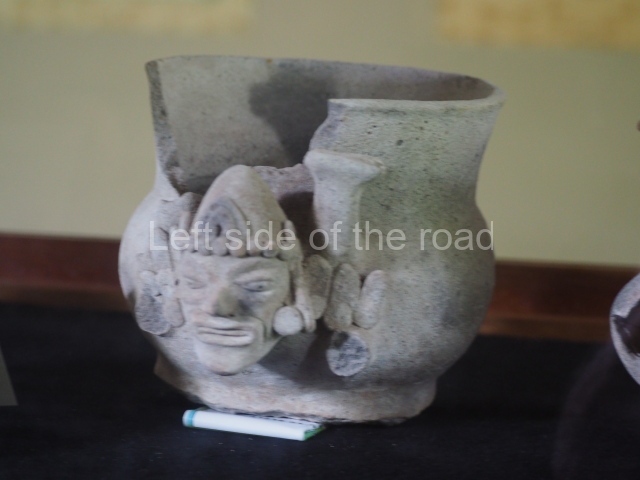

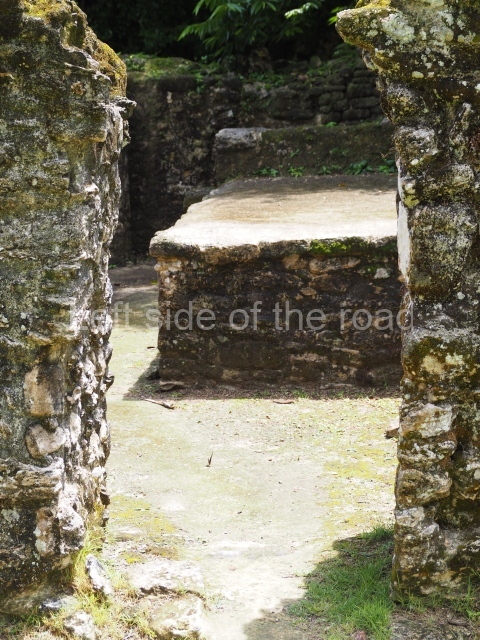

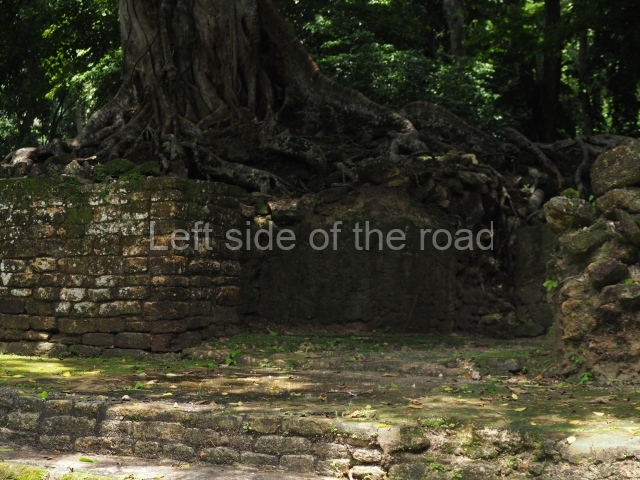

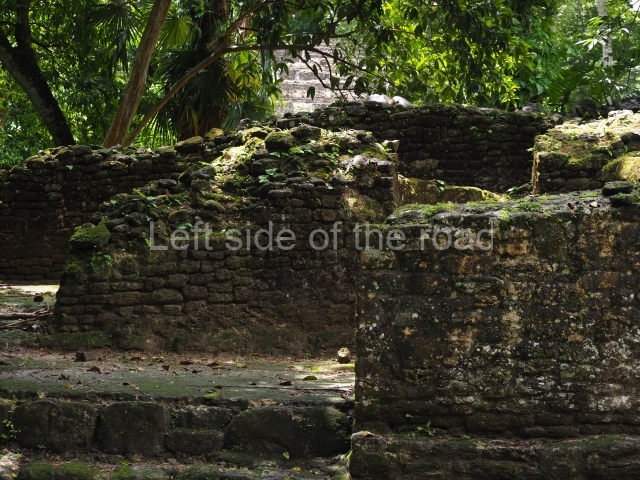

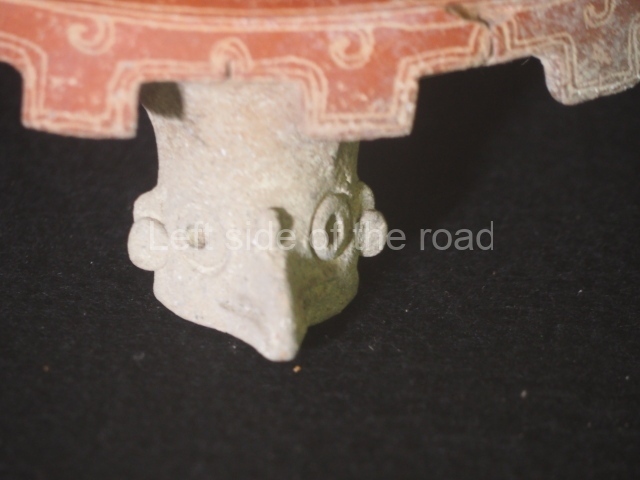

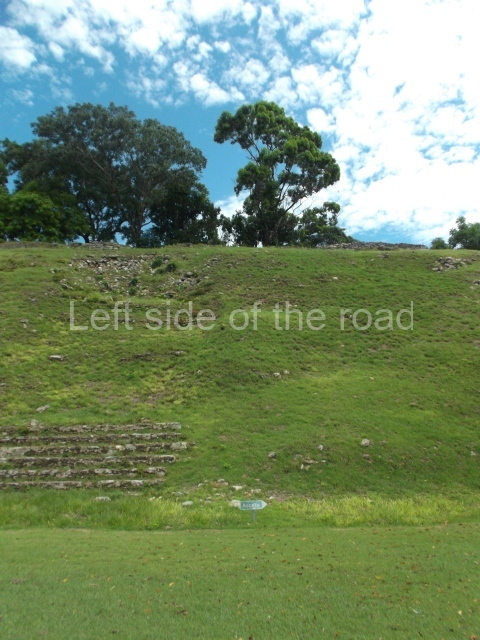

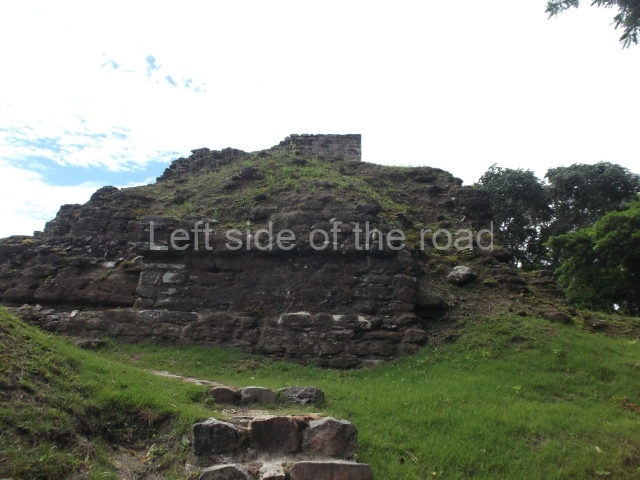

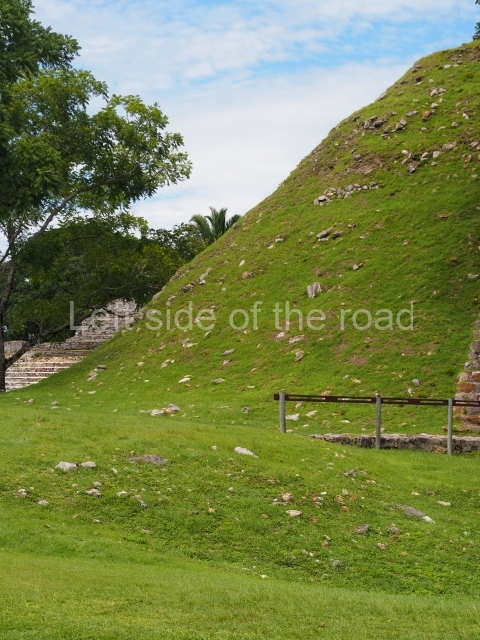

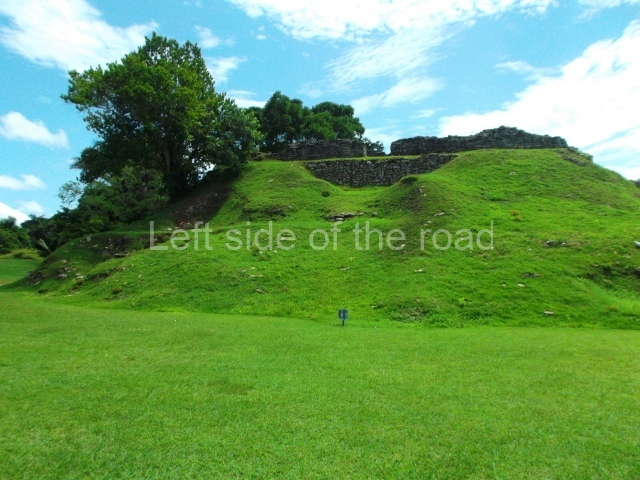

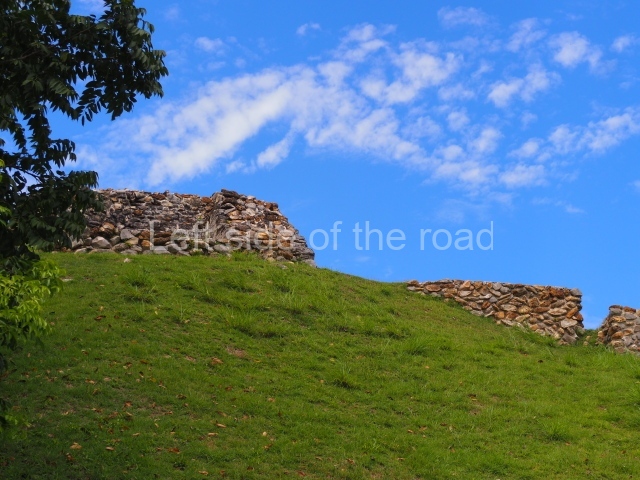

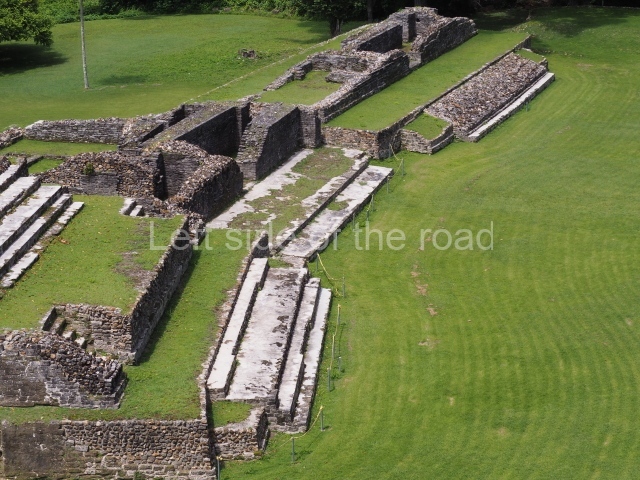

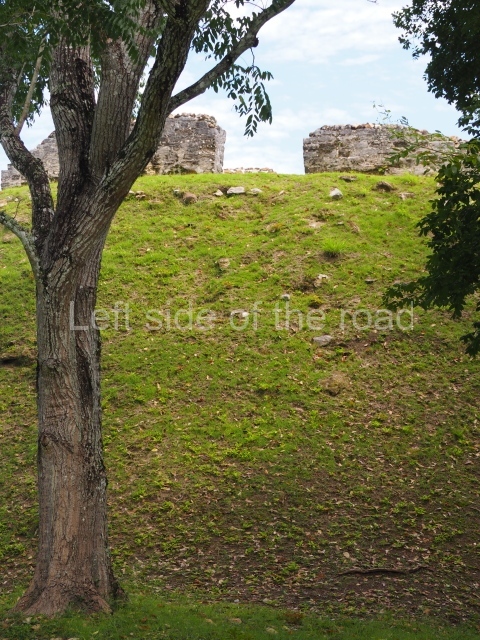

The only interesting building is Structure 7, the tallest and largest construction on the entire site. Its facade faces south, overlooking a plaza surrounded by mounds. It has various sub-structures, the most notable of which is the third one, a building with several rooms – three in a row and one on each side. This sub-structure was the only construction phase whose architecture was found in a relatively good state of preservation when the building was excavated, and it was therefore left visible and consolidated to accommodate visits by the public. The earliest part of the structure dates from the Late Preclassic, but it was subsequently remodelled and expanded until the Late Classic. It continued to be used during the Early Postclassic and an intrusive burial dating from the Late Postclassic was found on the stairway. The third sub-structure corresponds to the Early Classic and beneath the floor of the central room the burial of an elderly female was found, along with a wide variety of objects. The slightly later burial of an adult male was found in a tomb below the room at the front of the building. Due to the elaborate grave goods found, including a jadeite and shell mask, researchers believe that the person interred was an important ruler. During its final construction phase (Late Classic), the building stood approximately 17 m high. As a coastal site, it is surrounded by low rainforest and the land in the central part is not as fertile as in other areas to the north, near the River Hondo, where the Maya created raised fields to improve their farming productivity. Due to its location within the city of Corozal, the site can be easily accessed by tourists. Meanwhile, its situation by the sea creates an extraordinarily scenic setting.

From: ‘The Maya: an architectural and landscape guide’, produced jointly by the Junta de Andulacia and the Universidad Autonoma de Mexico, 2010, pp264-266.

How to get there:

From Corozal. Follow the road from the bus station that heads towards the Mexican border until you come to a roundasbout. Continue straight ahead and take the first road on the right, then a left and the site entrance is right in front of you.

GPS:

18d 24’ 08” N

88d 23’ 42” W

Entrance:

B$10