More on the Maya

Santa Rosa Xtampak – Campeche

Location

These ruins are situated at the top of a hill that was modified and levelled to build over a hundred masonry constructions, many with monumental proportions, that tend to form a regular pattern of plazas and quadrangular courtyards. The name of the archaeological area combines two words: Santa Rosa was a 19th-century hacienda, now lost, on whose land stood pre-Hispanic ruins or xlabpak (‘old walls’ in Yucatec Maya). The name used throughout the 19th century was Xlabpak de Santa Rosa, but in the following century it was changed to Santa Rosa Xtampak (‘in front of the wall’, ‘wall in sight’), a reference to the surviving walls of one of the main buildings. Santa Rosa Xtampak is situated some 40 km north-east of Hopelchen, which in turn lies 90 km east of Campeche City. Both parts of the route have an asphalt road.

History of the explorations

The first people to record the place were Frederick Catherwood and John Stephens, who visited it in the mid-19th century, described it and published an engraving of the Palace. At the end of that same century, Teobert Maler conducted a more detailed survey. In the 1930s and 1940s, a team from the Carnegie Institution, led by Harry Pollock, studied the ruins at Santa Rosa. In the late 1960s, Richard Stamps and Evan DeBloois (from the Brigham Young University in Utah) recorded and analysed the architecture, ceramics and chultunes at the site. In the 1980s more experts arrived: George Andrews (University of Oregon) and Paul Gendrop (Autonomous University of Mexico) to record the architecture, and William Folan and Abel Morales (Autonomous University of Campeche) to map the site. In the 1990s Nicholas Hellmuth photographed the buildings still standing; Hasso Hohmann and Erwin Heine produced a photogrammetric record of the Palace and conducted the first architectural restoration works under the supervision of Antonio Benavides C. (INAH). At the beginning of the 21st century, Renee Zapata (INAH) coordinated a programme of excavations and consolidation work at the principal constructions.

Timeline, site description and monuments

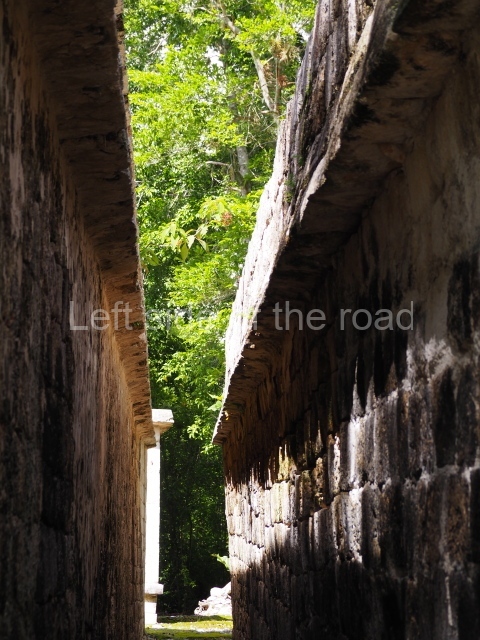

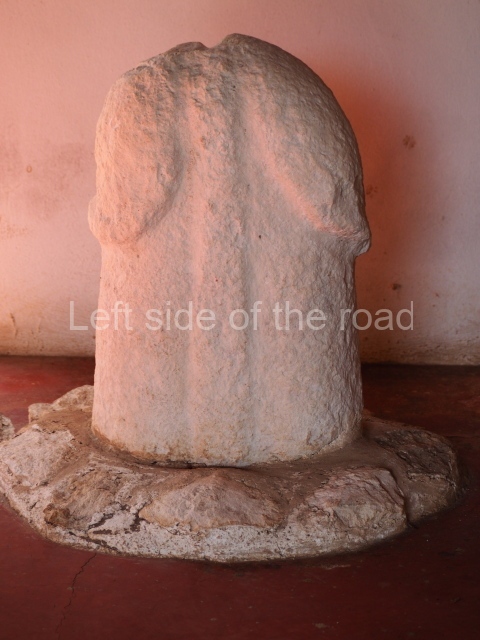

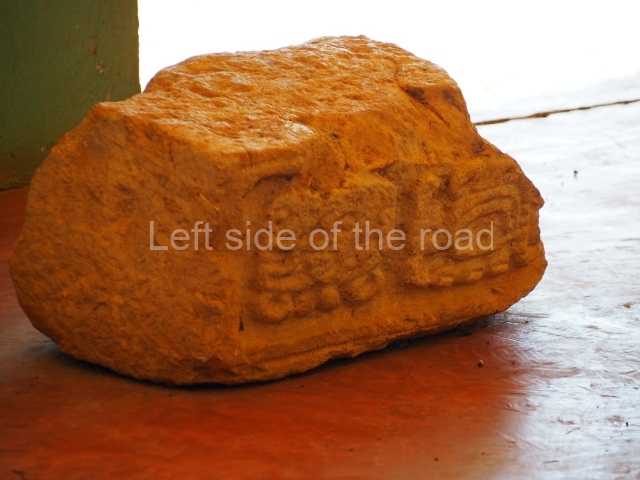

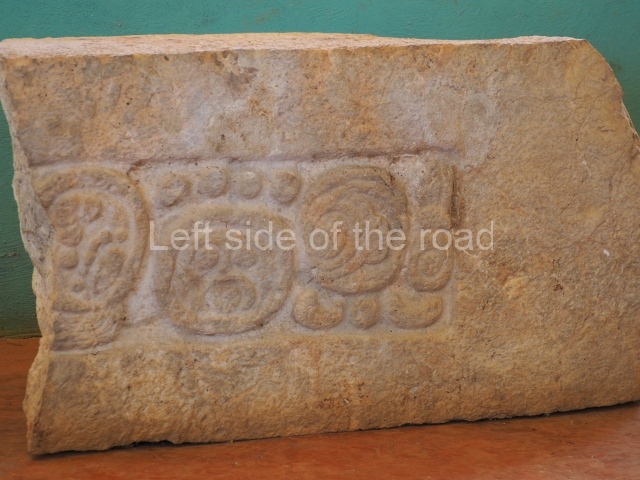

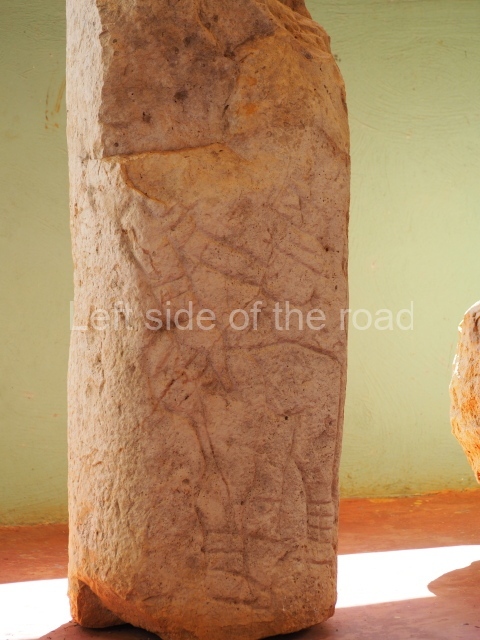

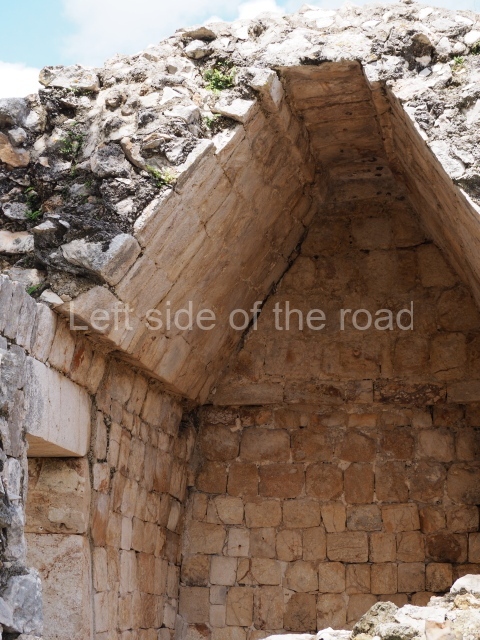

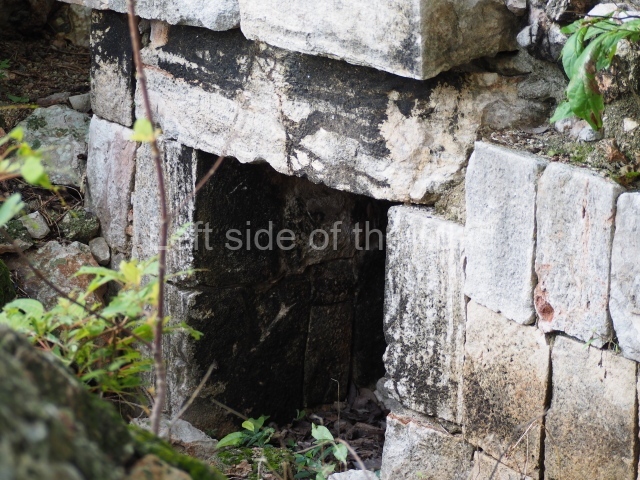

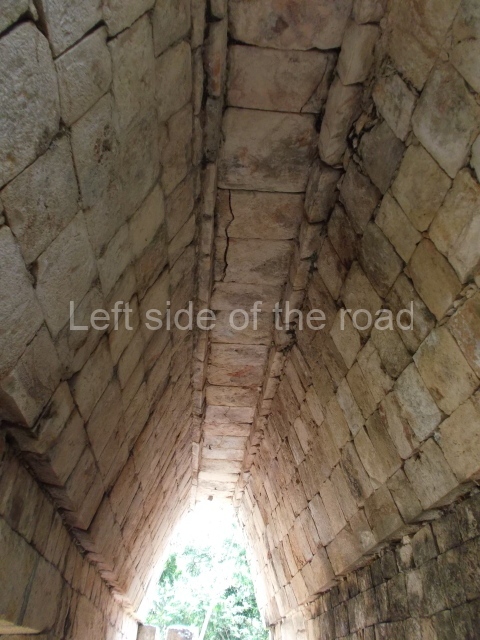

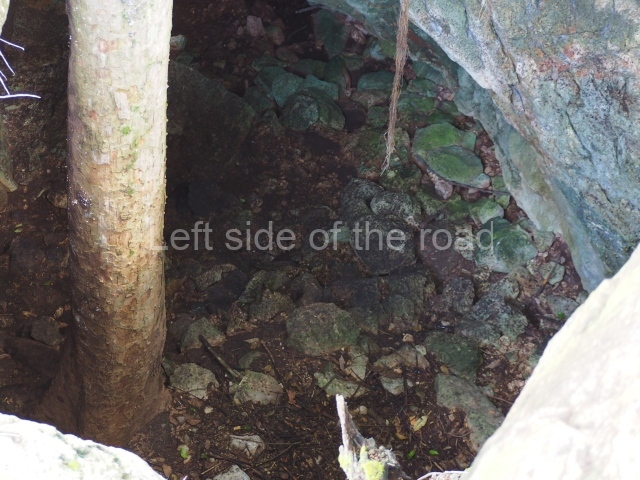

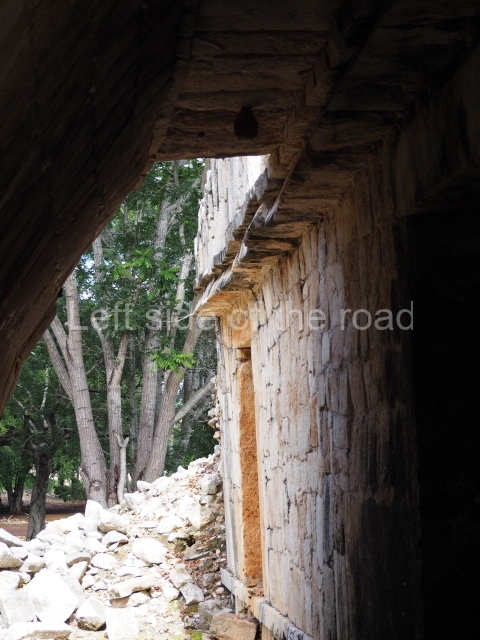

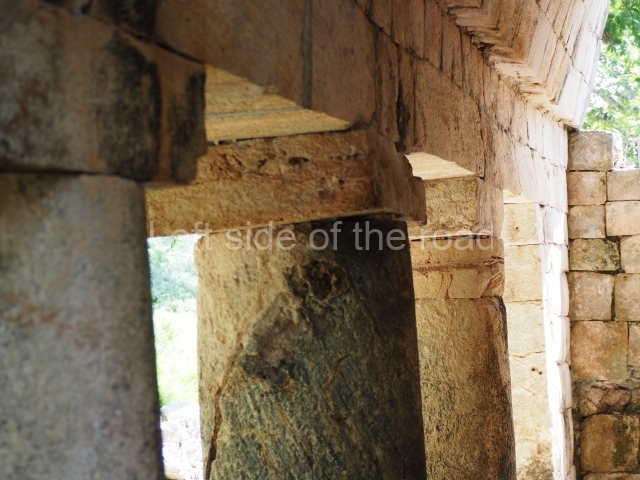

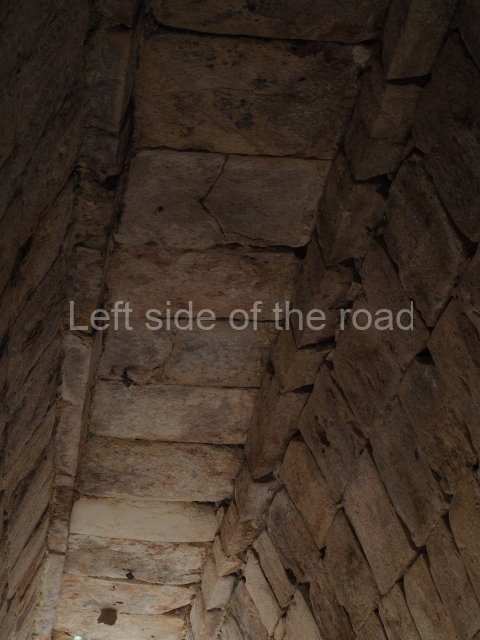

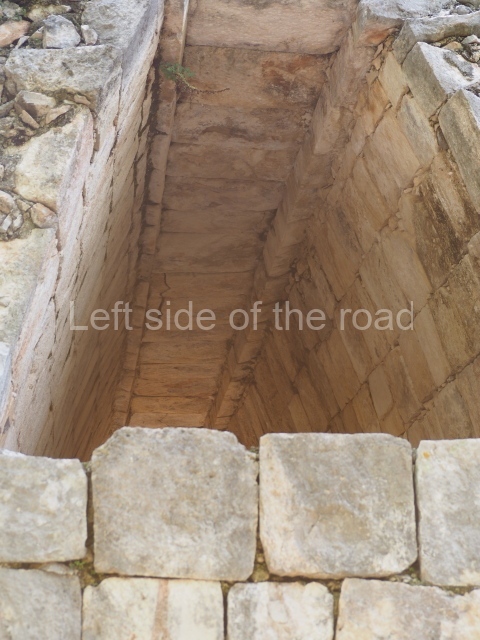

Eight stelae and three painted capstones with valuable information in the form of images and hieroglyphic inscriptions have been found at Santa Rosa Xtampak. The earliest date recorded thus far is AD 646 (Stela 5), although a preliminary analysis of the ceramics suggests that the site existed several centuries before the Common Era. The latest date, AD 948, was found on a capstone at the Palace. The ceramic materials also indicate a smaller human occupation in the Postclassic, and the city had already been totally abandoned by the time the Europeans arrived in the peninsula. The dominant architectural style is Chenes, characterised by constructions in which giant masks decorate part or the whole of the main facades. The motifs were achieved by creating mosaics with specially cut veneer stones, which were then stuccoed and painted in a variety of colours, especially red. Many constructions combine smooth panels with embedded columns on the walls or at the corners. The various entrances to the constructions are usually formed by masonry pilasters or columns. The corbel vaults usually rise directly from the vertical wall supporting them, with neither a slight recess nor soffit. Water was supplied via an intricate system of chultunes. Evan DeBloois recorded 67 such cisterns and based on their estimated maximum storage capacity the city is thought to have had a population of around 10,000.

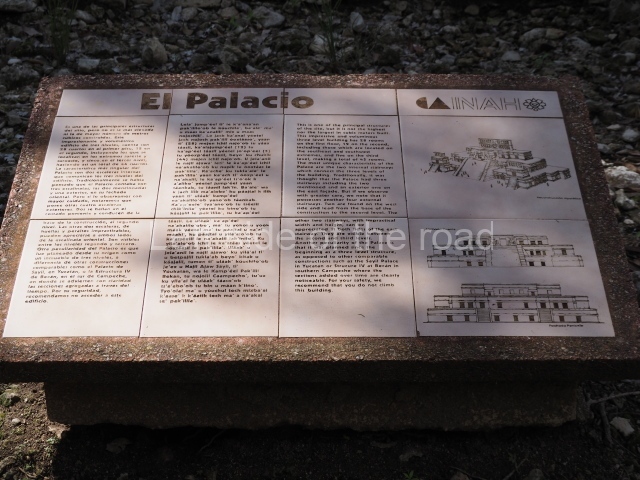

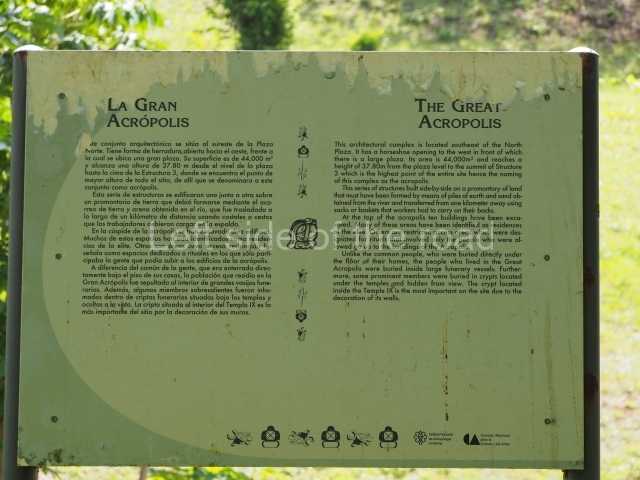

Palace.

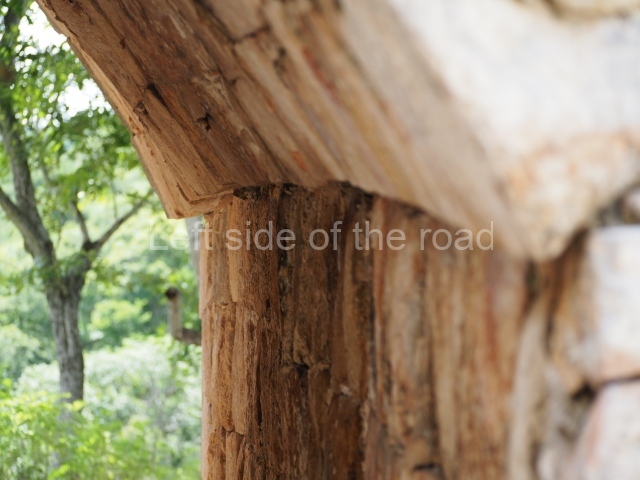

This building comprises 42 rooms on three levels. Approximately 50 m long, 30 m wide and 30 m high, it boasts a wide stairway on the east facade as well as additional entrances on the west side and two interior staircases to facilitate circulation between the rooms. These internal communication features are rare in Maya architecture and their corbel vaults turning on oblique plains have been studied by several experts. The generous proportions of the rooms, as well as their interior features and layout, suggest that most of them were residential quarters for rulers and their courtiers. The smaller rooms situated on levels 1 and 3 may have provided storage for the accessories used by the elite: large headdresses, ceremonial costumes, incense burners, sceptres, parasols, etc.

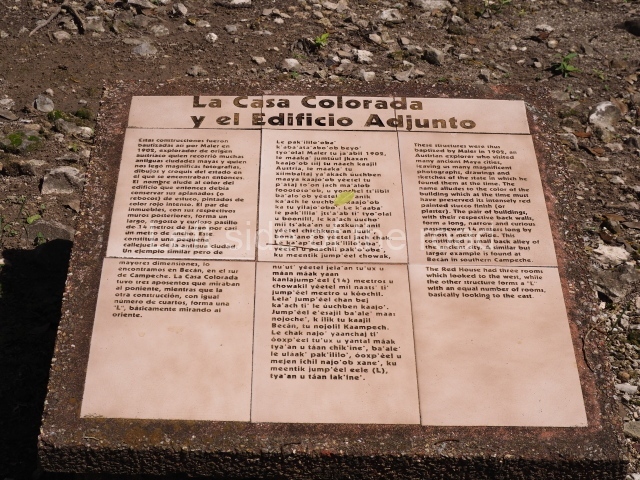

Building with the Serpent Mouth facade.

Thus christened by Maler, the building is characterised by a typical Chenes facade covered entirely by a fantastic giant mask. There are auxiliary rooms on both sides of the mask, but the most interesting aspect is the rear section, where the Maya builders created the image of a centipede. These arthropods (chapat, in Yucatec Maya) with their poisonous claws were thought to inhabit the underworld and were associated with the gods of the underworld. Situated next to this building is the Red House composed of three rooms, although only the rear wall is still standing today. The name is a reference to the traces of paint that could still be seen in the 19th century. A path leads from the west of this plaza to another group of buildings.

House of the Stepped Frets.

This construction is situated between the Building with the Serpent Mouth Facade and the Palace. In fact, it is another elite residential building, but this time on a single level. It contains spacious rooms that once had corbel-vault ceilings and a rhythmic pattern of slender columns forming part of the walls.

The plinth was decorated with the motif from which the building takes its name: stepped frets are a frequent symbol in the Chenes and Puuc styles, but they have also been found in many Mesoamerican regions. Their meaning remains the subject of debate, having been associated with stylised rattle snakes, the cyclical movement of the stars, opposites, etc. In Central Mexico they were called ‘xicalcoliuhqui’ (xicalli = drinking bowl; coliuhqui = twisted or reclining object).

Itzamna House.

This building stands near the Palace and also adopts a north-south longitudinal axis. The central part of the construction is clearly defined by a wide east-west corridor. Both entrances are flanked by the image of the Earth Monster made out of specially cut veneer stones to create a mosaic. This mythical creature was the personification of Itzamna, the creator god, sometimes represented as an iguana, sometimes as a crocodile and occasionally as an aged anthropomorphic being. The representation on this building at Santa Rosa Xtampak is another variant of the god that decorates the uppermost wall of the Palace (top and centre of the east facade). Other similar images have been reported in the Chenes region, such as at Nohcacab (Campeche), and in the Puuc region, such as at Uxmal (north-west sub-structure of the Governor’s Palace) and at Xburrotunich (near Oxkintok). Both wings of the Itzamna House contain an equal number of rooms, which once had corbel-vault ceilings.

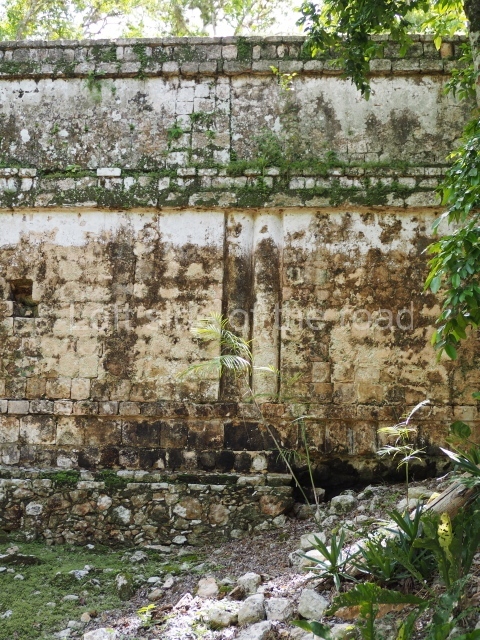

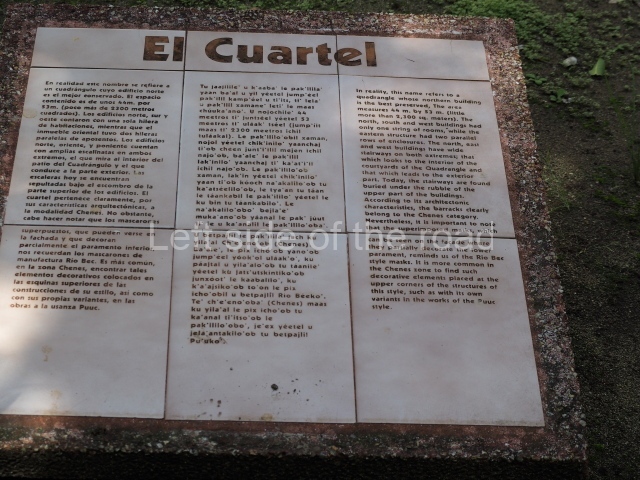

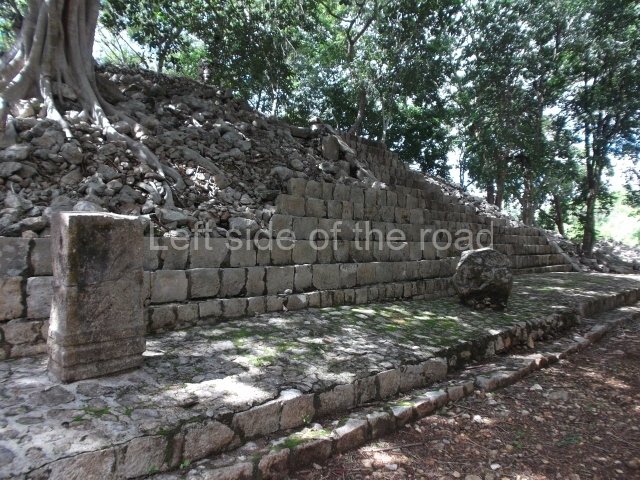

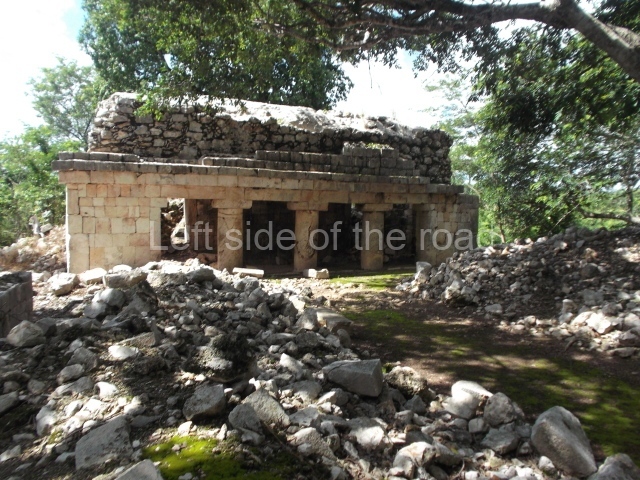

Cuartel.

This is a large quadrangular courtyard on whose north side stands a building with several room. In the middle are the ruins of a stairway and three rooms on each side. The middle rooms is flanked by stacks of stylised masks and the frieze on the medial moulding displays two folds that evoke the ‘broken mouldings’ that were popular during one of the Puuc architecture phases. Several other buildings at Santa Rosa Xtampak combine Chenes and Puuc features – a common situation given the physical and temporal (c. AD 600-800) proximity of the two regions. Another series of constructions nearby (south side of the quadrangle) display a wide stairway leading to the rooms. Between the steps it is possible to see the mouth of a chultun. These underground cisterns for collecting rain water were very common at sites in the Chenes and Puuc regions, both in the monumental precincts as described here and also in the sections occupied by modest dwellings.

The name of this architectural group (cuartel is the Spanish word for ‘barracks’) does not actually have any military associations. It was thus called by the locals in the mid-19th century (when the site was reported by John Stephens). In this respect, it resembles the ‘Nunnery’ Quadrangle at Uxmal, which again has no logical basis but spread in the 16th century when the first Spaniards visited it.

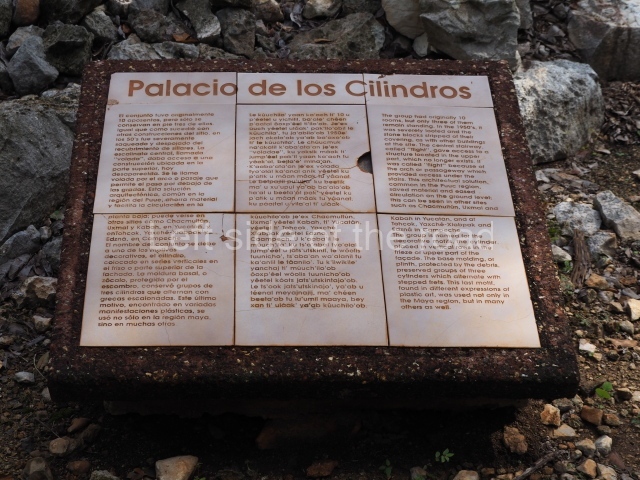

South-east quadrangle.

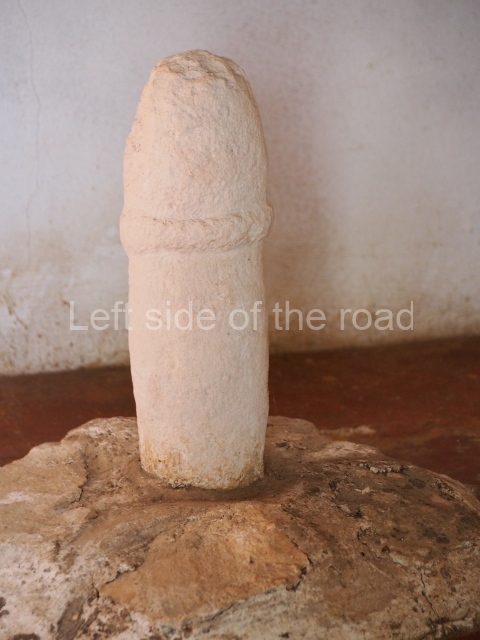

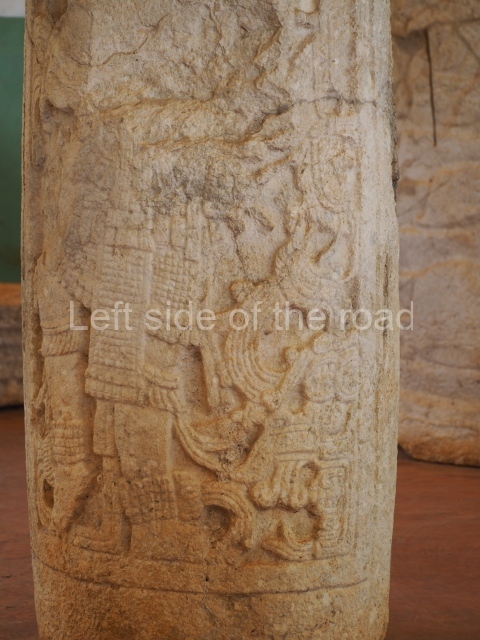

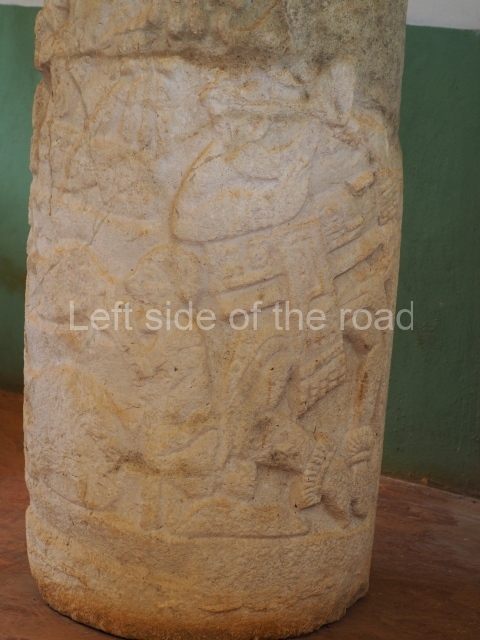

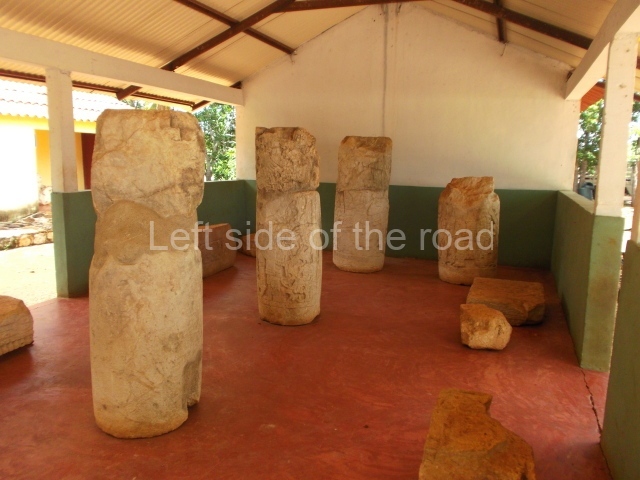

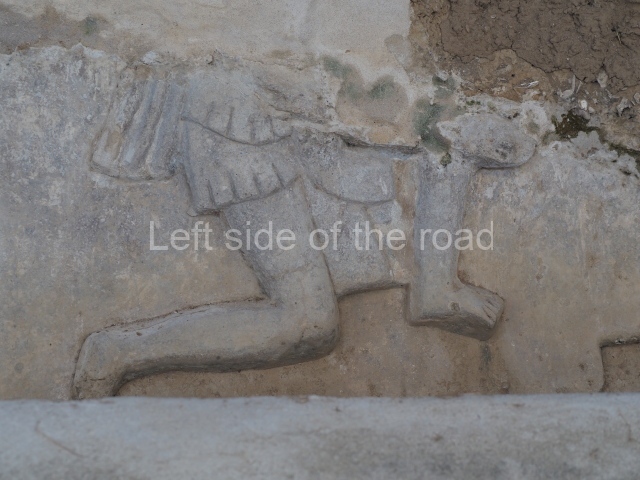

The entrance to this architectural group is via the north-west corner, given that the east, south and west ranges are connected at their corners. All of them once had corbel-vault rooms. The north range is an independent construction and it was here that researchers found various cylinders with reliefs depicting a god with large pumpkins that extend downwards, creating a type of fabric on which he seems to walk or dance. The sculptural style corresponds to the Terminal Classic (between AD 800 and 900). In the middle of the quadrangle is a low platform. The east range displays thick columns forming entrances. These supports are crowned by mouldings with three elements, almost identical to those reported at Ek’ Balam in eastern Yucatan.

Several points indicate that this architectural group was created at different times. In the south-east section of the quadrangle, various veneer stones with unconnected reliefs have been used as part of the wall but evidently recycled from an earlier construction. Beyond the wall a passageway leads to rooms where the corbel-vault ceiling seem to be misaligned – another indication of the gradual construction of the group.

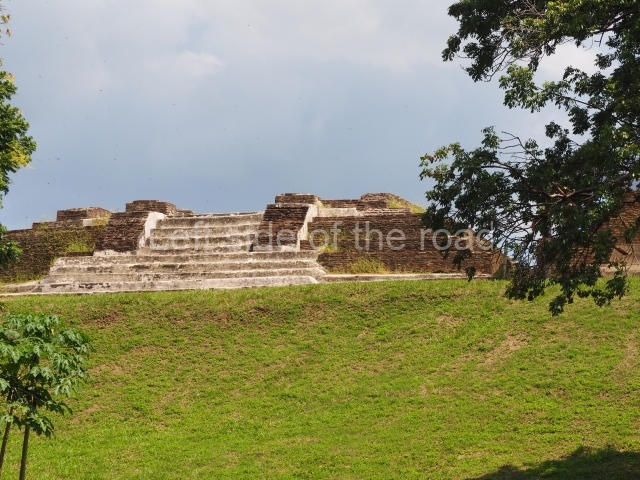

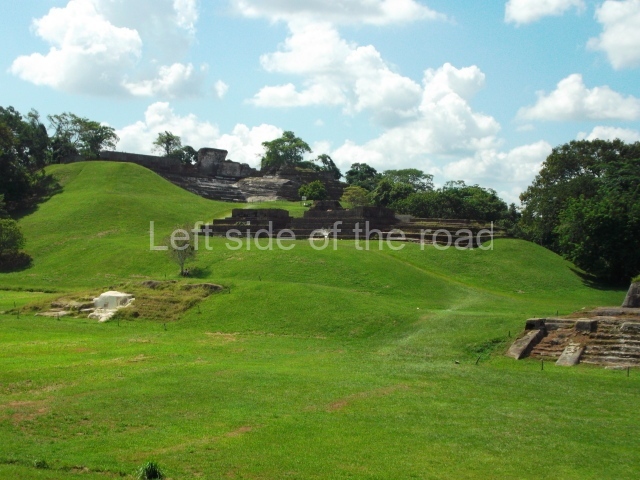

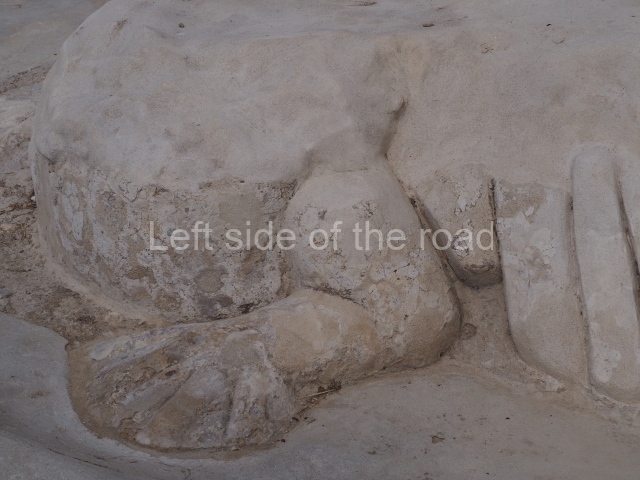

Star hill.

The South Plaza at Santa Rosa Xtampak is bounded to the north by an enormous pyramid platform, nowadays known as Star Hill, at whose base it is still possible see some of the megalithic steps that facilitated its access. These elements correspond to the earliest occupation of the settlement, like the Petenstyle stairways with giant blocks reported at other regional capitals of the peninsula, such as Edzna, Dzehkabtun, Izamal and Coba. The top of Star Hill is the highest point of the core area of Santa Rosa Xtampak. However, archaeological explorations have not yet been conducted in this part of the site and it is still covered by vegetation.

Importance and relations

Santa Rosa Xtampak is one of the most important Maya cities in north-eastern Campeche. The labour expended to build the pyramids, palaces and temples reveals a solid political structure that controlled a large region. The rulers commissioned official texts for stelae and the paintings in several rooms; they maintained long-distance trade links and played a vital role in the local economy, especially during the Late Classic (AD 600-900). The eight stelae recorded thus far contain dates ranging from AD 646 to 911.

From: ‘The Maya: an architectural and landscape guide’, produced jointly by the Junta de Andulacia and the Universidad Autonoma de Mexico, 2010, pp 311-315.

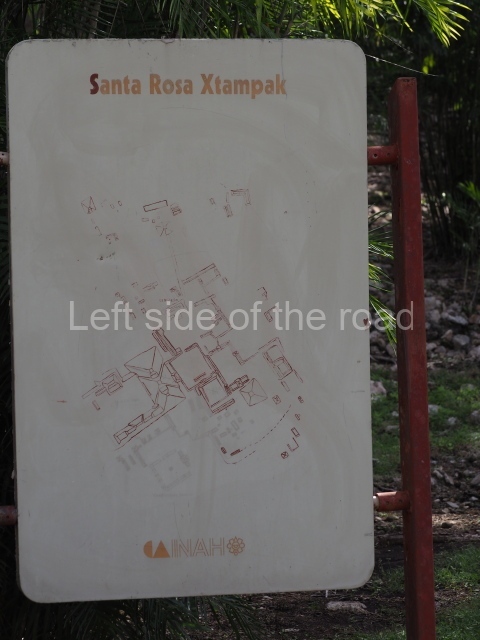

1. Palace; 2. Building with the Serpent Mouth Facade; 3. Red House; 4. House of the stepped Frets; 5. Itzamna House; 6. Cuartel; 7. Ball Court; 8. South-east Cuadrangle; 9. Star Hill; 10. West Group; 11. North-west Group; 12. North Group.

Getting there:

From Hopelchen. It’s not easy without your own transport. However, tuk-tuk’s will take you there, wait for two hours and then take you back to Hopelchen. You have to decide what price you’re prepared to pay. A slow tuk-tuk takes about 90 minutes each way.

GPS:

19d 46’ 20” N

89d 35’ 50” W

Entrance:

M$70