More on the Maya

Altun Ha – Belize

Location

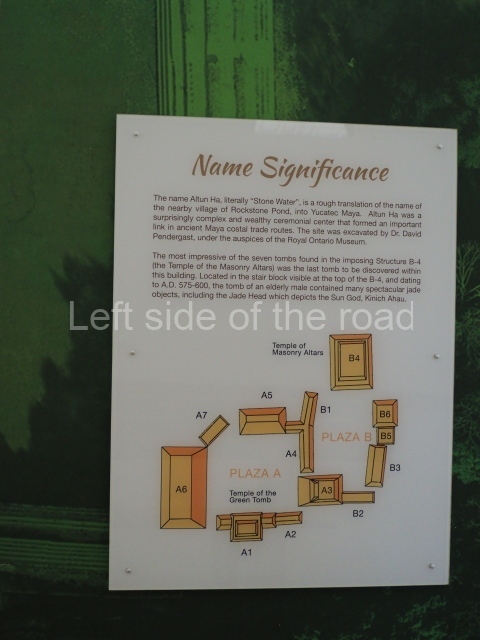

The original name of the site is not known. Altun Ha is the name of a nearby village, which in Yucatec Maya means [stone pond or lagoon). Due to its proximity to Belize City, this is one of the most visited sites. It covers an area of nearly 6 sq km and has over 500 visible structures, although the part that has been restored and is open to the public is relatively small. The constructions in the ceremonial precinct correspond mainly to the Classic period. During the excavations various unusual objects were found, corroborating the hypothesis that the site was an important link between the maritime trade routes and the inland: flint eccentrics, fine imported ceramics and the largest piece of jade ever found in the Maya area – an anthropomorphic head representing K’inich Ahau. This comes from Tomb B4/7 (2nd. A). The site is an hour by car from Belize City, taking the Northern Highway; when you reach mile marker 33, turn east and continue along the Old Northern Highway, where the signposts will lead you to the site. There is a car park, a visitor centre, and shops selling local handicrafts and food.

History of the explorations

In 1957 Altun Ha was recognised as an archaeological site by A. H. Anderson, the then archaeology commissioner in Belize, who conducted the first excavations. In 1961 William R. Bullard studied some of the materials. Between 1964 and 1970, David Pendergast of the Royal Ontario Museum carried out extensive excavations. Joseph O. Palacio began restoration work at the site in 1971 and continued until 1976. In 1978 Elizabeth Graham also conducted a series of restoration works. Between 2002 and 2003, as part of the Tourism Development Project supervised by Jaime Awe, Juan Luis Bonor and Doug Weinbury, the structures in central part of the site were restored and opened to the public.

Pre-Hispanic history

The earliest evidence of a settlement on the site dates from 200 BC. The oldest permanent construction is situated west of the central area and is not open to the public. Structure F8, known as the Reservoir Temple, is situated less than a kilometre south of Plaza B. An offering was discovered there, containing green obsidian eccentrics and blades from central Mexico, along with other imported objects not normally found in this part of the Maya area. The green obsidian may well have come from contact with Teotihuacan. The earliest building in the central precinct is Structure Al, built around 100 BC. It adopts the form of a temple and is close to the main reservoir. Subsequently, in the Early Classic (circa AD 250), building activity was concentrated in the part now open to the public. This remained the most important precinct at the site until the Late Classic.

Site description

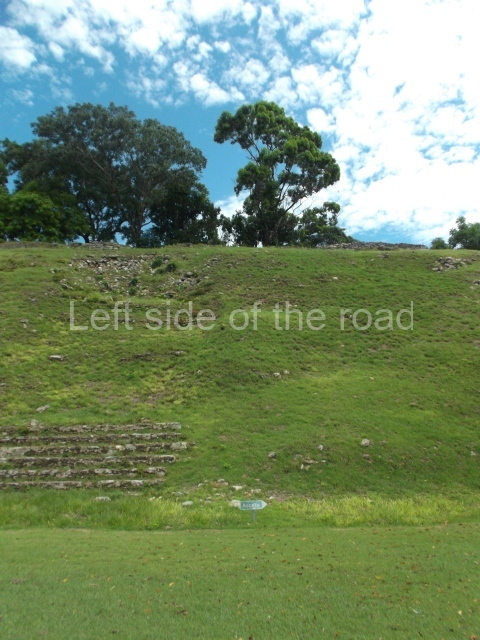

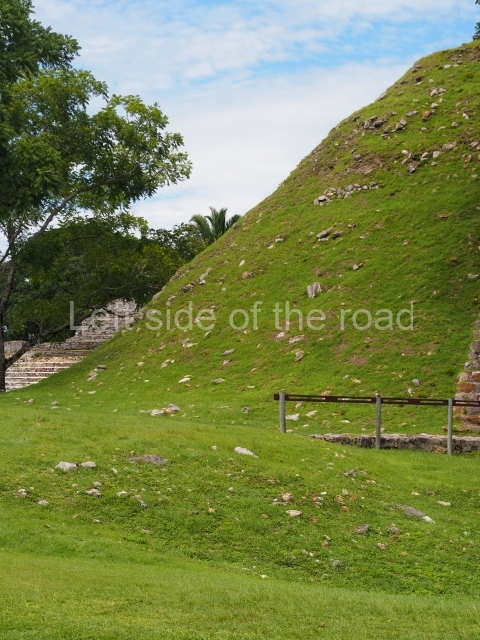

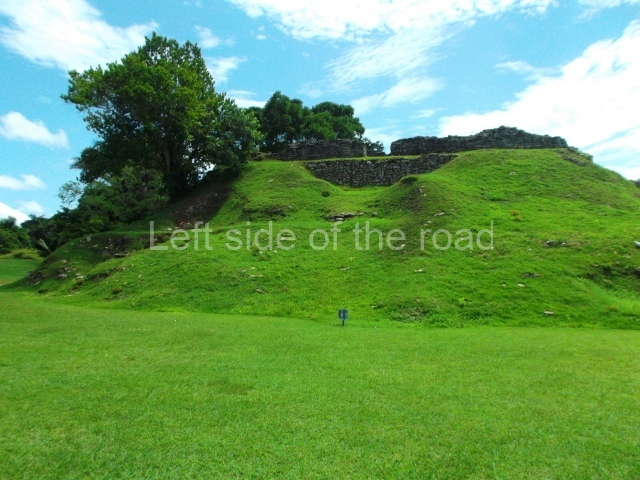

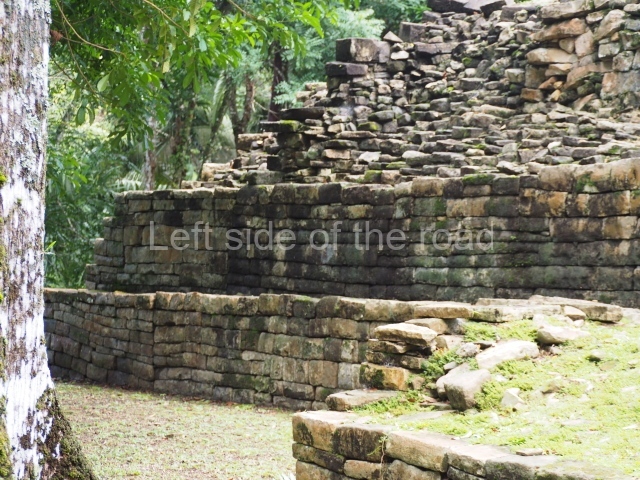

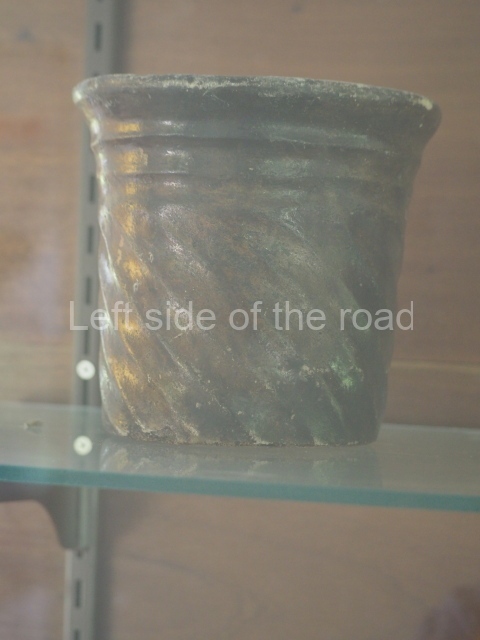

Plaza A, in the northern section of the site, was the principal ceremonial precinct until the end of the Early Classic (circa AD 550), when the construction of Plaza B commenced, immediately south of the former. Buildings continued to be erected until AD 900 and the site was occupied for a further 100 years, although no new construction took place. In fact, a century and a half prior to the end of the building activity, the existing constructions were already decaying. Subsequently, the city was abandoned and then reoccupied in the 13th and 14th centuries. Plaza A is the largest, although no monuments or stelae were found in front of the buildings, Temple 1 displays various construction phases and its final form consists of a platform with terraces, built between the 5th and 6th centuries. Slight modifications were conducted during the course of the following centuries. The building originally comprised several rooms in the upper section and a broad stairway that reached almost to the top of the structure. A tomb was found inside the temple; dating from approximately AD 550, it is the oldest in the central precinct. It takes its name, Green Tomb, from the fact that it contained over 300 jade objects, as well as shell necklaces and ornaments, stingray spines, ceramic vessels, flint eccentrics and perishable materials such as animal skins, cloth, wooden objects and what are thought to be the remains of a bark paper codex, whose fragility and fragmented condition have prevented it from being reassembled.

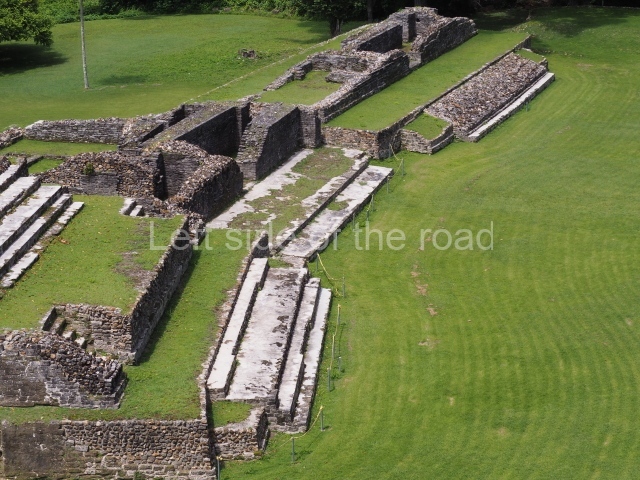

Structure A2, a platform with rooms at the top, and Structure A8, a residence, are nowadays connected, although in their earliest construction phases they were separate buildings, structure A3 is the smallest temple in Plaza A. Meanwhile, structure A4 situated in the south-east section of Plaza A appears to have been a long, narrow platform with no buildings on the top, and it may well have served to delimit Plazas A and B. Plaza B is composed of various residential constructions and large temples. A group of three buildings (B3, B5 and B6) forms the south boundary: originally, these were separate structures but they were subsequently connected during the final construction phase.

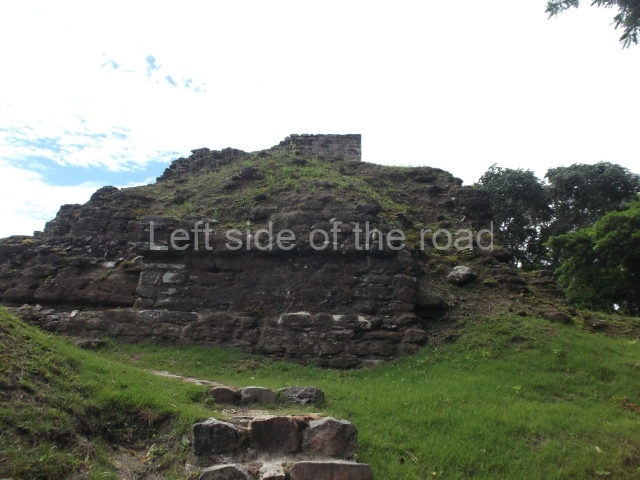

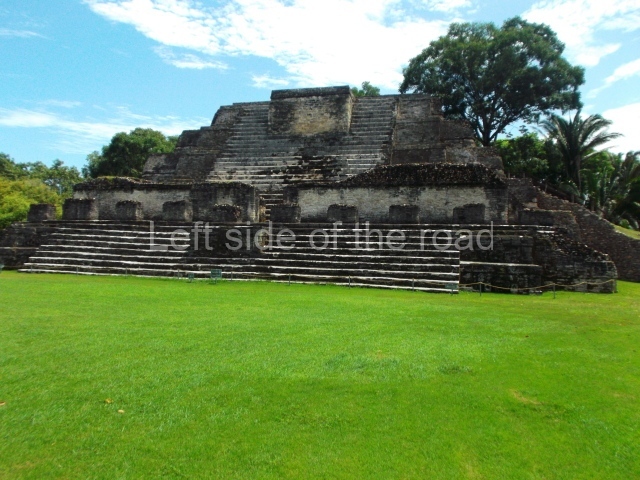

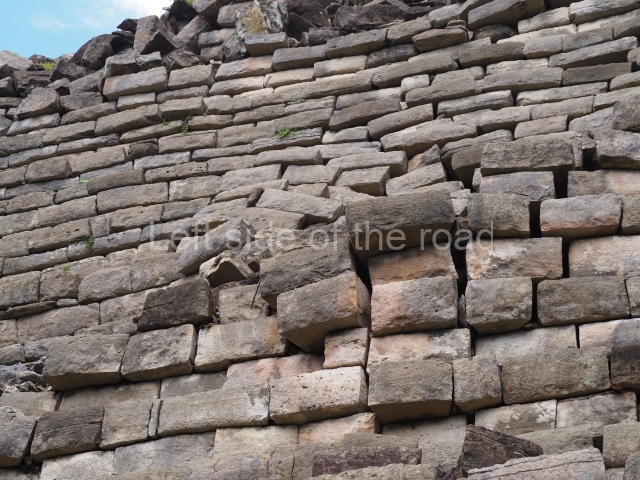

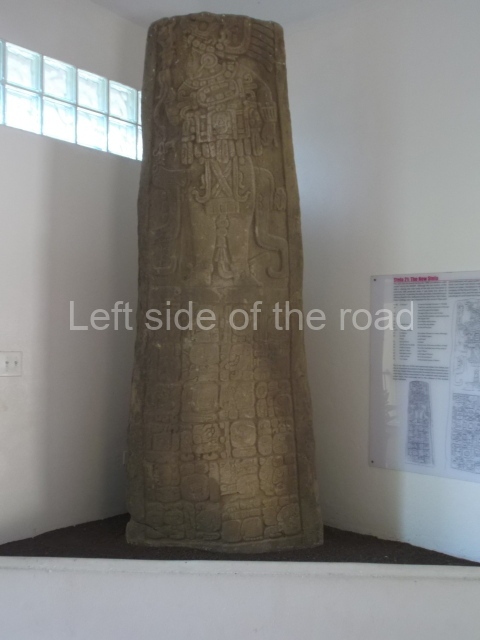

Structure B4 is the most imposing building on the site and is known as the ‘Temple of the Masonry Altars’. It displays eight construction phases and stands nearly 18 m above the plaza. Seven tombs belonging to the Altun Ha elite were found inside this structure. The most impressive of them was discovered inside the rectangular block at the top of the building: Tomb B4/7 (2nd. A), which corresponds to the end of the Early Classic (AD 575-600). The remains of an elderly male were found in the tomb and the grave goods contained spectacular jade objects, including the head of the sun god, K’inich Ahau. This corresponds to the Mac phase (circa AD 600); it is 14.9 cm high and weighs nearly four and a half kilos. A variety of perishable materials were also found, such as ropes, clothing and wooden objects that do not normally survive in the Maya lowlands due to the damp climate.

From: ‘The Maya: an architectural and landscape guide’, produced jointly by the Junta de Andulacia and the Universidad Autonoma de Mexico, 2010, p273, pp276-277.

- Plaza A; 2. Temple A1; 3. Structure A2; 4.Structure A3; 5. Structure A4; 6. Structure A5; 7. Structure A6; 8. Plaza B; 9. Structure B1; 10. Structure B2; 11. Struture B3; 12. Structure B4; 13. Structure B 6; 14. Structure B5.

Getting there:

From Belize City. There is a bus from Belize City whose final destination is Maskall and which passes the end of the approach road to the site – about a 2 mile walk. However, I have not been able to find any timetable for that bus – or whether it is possible to make the trip and back in a day. There was a bus which would have left Belize City at around 12.00 but that is not guaranteed. Otherwise, you could catch a bus to Sand Hill and get off at the junction of the Old Northern Highway. This is the road that goes within 2 miles of Altun Ha. There you either hitch or negotiate the cost of the lift. It’s all a matter of chance and luck whether you either get or lift or have to pay or not.

GPS:

17d 45′ 27″ N

88d 21′ 23″ W

Entrance:

B$10