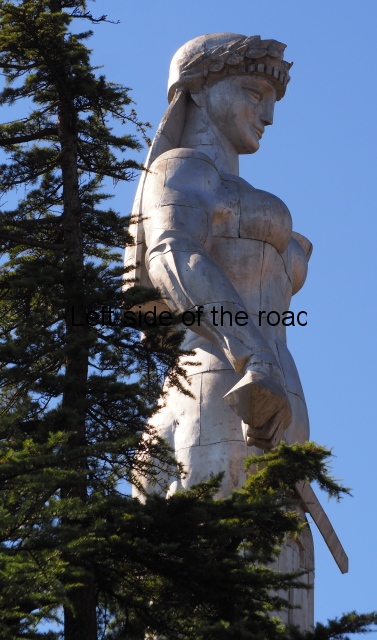

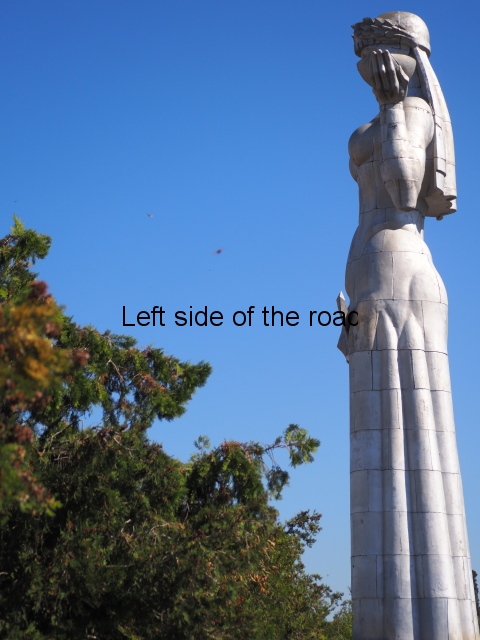

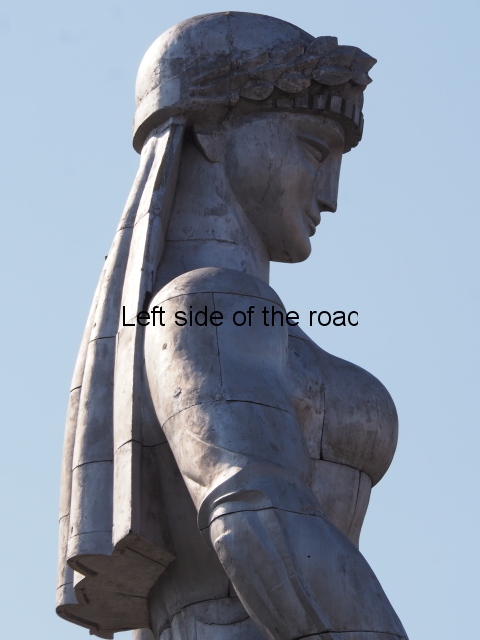

Mother of Georgia from Tbilisi old town

More on the Republic of Georgia

Mother of Georgia – Kartlis Deda – Tbilisi

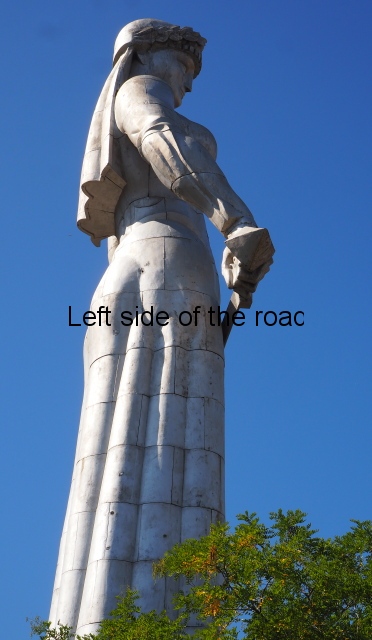

Kartlis Deda, the 20m high, aluminium statue that presently stands on the top of Sololaki hill, overlooking the Georgian capital of Tbilisi, is the work of the sculptor Elguja Amashukeli.

And that seems to be all that is agreed upon by those who make reference to one of the most notable landmarks in Tbilisi. When I decided to write about this statue I thought it would be an easy and straightforward exercise – a few facts, a slide-show and them move on to the next topic. But that’s not the case.

To explain.

The Name

Kartlis Deda is the transcription from the Georgian to the Roman/Latin alphabet but there’s no agreement on what should be the English translation. Most references like ‘Mother of Georgia’ but that version presents difficulties when considering what the image represents to the population of the country. This translation gives the impression that the Mother gave birth to the country – strange but in pre-historical mythology even stranger ideas were considered valid.

Contrast this interpretation with ‘Mother Albania’ – the name given to the statue which stands high above the city of Tirana, Albania, in the National Martyrs’ Cemetery. Here ‘Mother Albania’ stands as a protecting symbol for all the people and it’s from this concept that we get the term ‘Motherland’. But I’ve never seen any reference to ‘Mother Georgia’.

It gets even more complicated. Another translation is ‘Mother of Georgians’. This suggests that she is the mother of all those who are genetically Georgian. The problem here is that Georgia is, and has been for centuries, a country that has had large populations who were not genetically Georgian. Now many of these people can trace their ancestors back generations, they would probably – in many ways – consider themselves Georgian but not according to the ‘Mother’. So we have a national symbol which doesn’t represent all the people within the national borders – potentially somewhat divisive I would have thought.

Then the third translation is ‘Mother of a Georgian’. This is even more complex. Which Georgian? A male or a female? Why was s/he chosen? And why doesn’t anyone know who s/he is? And why should that have any meaning for the millions of other Georgians (or the people who live in the country)?

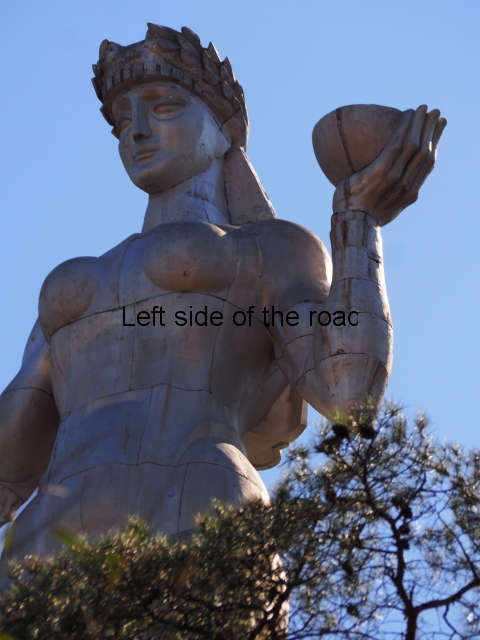

The Symbolism

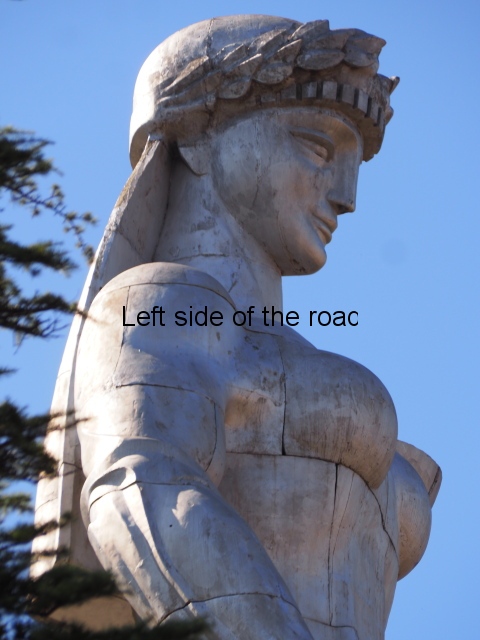

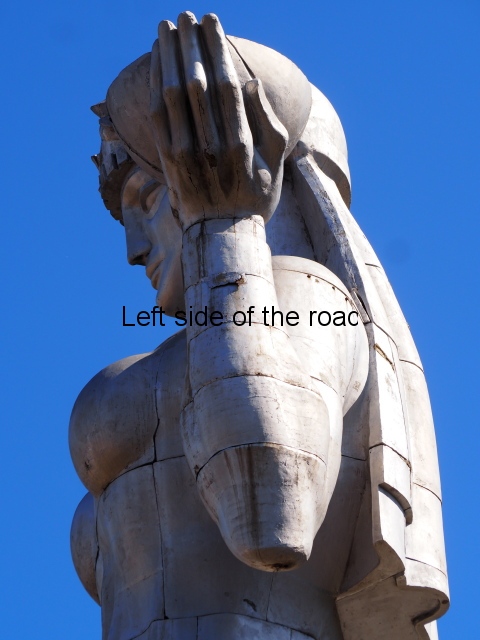

When it comes to the symbolism there’s even a difference of opinion here. There seems to be general agreement that the bowl she holds in her left hand symbolises hospitality, the welcoming of a stranger, or visitor, with a offering of wine – which was first cultivated in Georgia around 6,000 years ago.

The sword, however, has a couple of interpretations. One is that it is to fight off any enemies and that seems fair enough and possibly valid in the past. The other is that it represents the Georgians’ idea of independence and freedom. If the second interpretation is pushed then Deda will have to give up her sword – although Georgia is not too friendly with Russia at the moment they would dearly love to become part of the European Union – like most so-called ‘independent’ countries (or wanting to be countries) many ‘nationalists’ want to change one dominant power for one, more powerful, multi-state entity.

The Date

Next there’s even a disagreement about when the statue was erected. Many refer to 1958, as the 1,500th anniversary of the founding of the settlement of (what is now) Tbilisi. But in the only ‘authoritative’ source I’ve come across it states 1959 – in the Georgian text as well as the English translation.

Two Versions

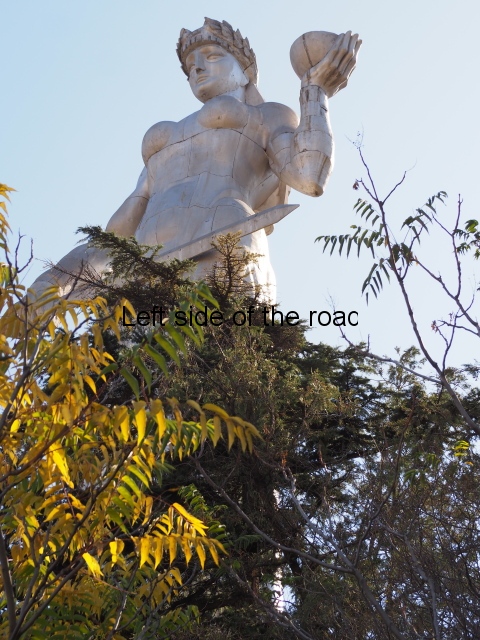

Probably the most interesting point I came across in my research was the fact that what stands above Tbilisi now (whatever name it might be called in English) is not the same statue that was erected in 1958 (or 1959) – see, it starts to get complicated.

This reference is in a digital book entitled ‘Elguja Amashukeli – Sculpture, Painting’, published in 2013. It was a collaborative affair but the text is attributed to an Art Historian called Tamta-Tamar Shavgulidze with another Art Historian, Nana Shervashidze, as editor.

”The Mother of the Georgians’ also underwent changes later by the efforts of the author himself and became more womanly: the masculine image was transformed into a feminine one.’ p6

The original mother

And here is the only picture I’ve come across of the original. Quite different from what we can see now and when comparing the ‘before and after’ the text by Tamta-Tamar Shavgulidze below makes sense.

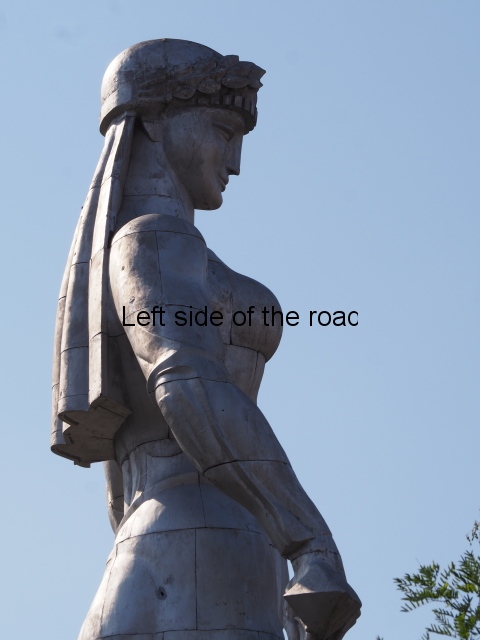

‘New’ Mother of Georgia

‘In 1959, in connection with the 1500th anniversary of founding Tbilisi, he [Elguja Amashukeli] made a model for the monument ‘The Mother of Georgians’ which was erected in 1959. The monument was made of steel [this must be a bad translation, it would have been aluminium from a aircraft factory] sheets at the Tbilisi aircraft factory, while the base was a wooden sculpture which could become rotten with time. Besides, although ‘The Mother of Georgians’ had a symbolic charcater, Elguja was worried that he had failed to give his creation, so aggregated and original, the form of a round sculpture. That was why, quite a long time after, he worked on the sculpture for nearly one year, and as a result the subject remained the same although the face and the body became more feminine having acquired the elements of a round sculpture.’ p32

Unfortunately, there’s more confusion caused in the text of this book. The dates under the image of the ‘Old’ Mother are 1958-1963 yet the date under the ‘New’ Mother is 1995. Also when it comes to the 1995 statue it is called ‘Mother of Georgians’ whilst in 1958-1963 version she is called ‘Mother of Georgia’ – probably the most schizophrenic sculpture I’ve encountered.

‘I gave preference to the ‘old’ version,’ p6,

Shavgulidze writes, and I think I agree.

How Georgian sculptors portray the female body

Whichever version you look at the strange breasts (even more pronounced on version one) are ‘noticeable’ – perhaps where Madonna got her ideas. I thought this was a later, revisionist affectation but it obviously was accepted in a very public arena at the end of the 1950s. Whether this was following a Georgian sculptural convention that had been around for some time I don’t know. Yet another gap in my knowledge I’ll try to fill at some time in the future.

Mother of Georgia

This also might make some of the points I made in reference to the young woman in the terracotta sculpture of telecommunications workers in Tskaltubo desiring of revision – again when there’s more clarity of the local conventions.

What is clear, however, is that this is a clear departure from what had been the tradition of Soviet Socialist Realism (as seen in Tbilisi on the facade of the Rustaveli Cinema) and whether this was as a result in the changing attitudes in the Khrushchev ‘era’ or just a maintenance of a local approach remains to be seen.

At least I haven’t seen anything as bad as the ‘modern’ statue of the Albanian People’s Heroine Liri Gero that appeared in Fier a few years ago.

Workers nominate for art prize

One other notable point that comes from this study on Amashukeli is that;

‘ .. ‘The Mother of Georgians’ was nominated for the Rustaveli Prize by the staff of the Kirov Machine-Tool Plant together with the Union of Artists and the Union of Architects.’ p5

After the 20th Congress of the Communist Party of the Soviet Union in 1956 the road to Socialism became rough but still, at least in the early years, there existed a situation where workers in a local factory were making nominations for an art prize. Where have you ever seen that in present day capitalist societies?

Another ‘Mother’

Although ‘The Mother’ is big in Tbilisi I haven’t been aware of seeing such statues in other parts of the country. Perhaps I’ve just missed them or if they did exist in the past they might have been victim of anti-Communist vandalism.

Mother of Georgia – Tskaltubo

However, there is at least one example – and that’s in the spa town of Tskaltubo. On the east wall of the ‘It’s my business’ Sanatorium there’s a metal bas relief with the figure as ’rounded’ as the one in Tbilisi became. It’s high up on the wall and that might have saved it from destruction. In fact it looks down on and across the road from the telecommunications workers’ mural.

How to get to ‘The Mother of Georgia’/’The Mother of Georgians’/’The Mother of a Georgian’

The easiest way to get to the top of Sololaki Hill is to take the cable car from the southern end of Rikhe Park, on the other side of the river from the old town. This runs from 10.00 – 00.00 and costs GEL2.5, but you’ll need the Tbilisi Transport Card.

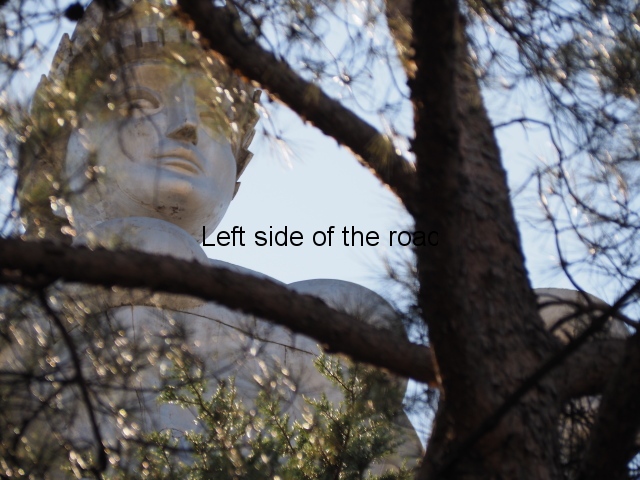

If you want to walk then head down Shalva Dadiani Street from Freedom Square, at the end turn left along Lado Asatiani Street for 100 metres or so to Betlemi Rise on the right that ends at a set of steps (view from photo at head of post). This is a steep climb but there are good steps all the way. Also passes close by a couple of churches and a half way viewpoint.

Mother of Georgia from footpath

This approach also gives you the opportunity to have a reasonably close look at the statue from the front. Once at the top the structure is so close to the edge that when you are at the plinth and look up you are looking up Mother’s nose.

More on the Republic of Georgia