An angry Communist threatens Franciscan friars

More on Albania ……

Anti-Communist paintings – Shkodër Franciscan Church

Religion is interesting in Albania. Travelling around you can’t help but notice the new mosques and churches (both Catholic and Greek Orthodox) that are appearing everywhere. Whether there’s a real need for so many is debatable, I’ve hardly seen any evidence of what could be called a ‘religious revival’. However, the Catholic Church, in particular, is on the offensive and that can best be seen with the anti-Communist paintings in the Franciscan Church in Shkodër.

When I’ve gone past mosques after the call to prayer there’s hardly as much activity as there is on a regular basis at the mosque in Liverpool 8. And when I’m expecting there to be the 6 o’clock mass in the Catholic Churches there have been even fewer people in the church at that time than there might have been a few hours earlier. Or the churches are locked up. I don’t really know the timetable used by the Greek Orthodox church (and I’m hardly an authority on any other religious sect really) but I’ve not seen crowds streaming from their doors either.

I’ll no doubt return to religion in other posts but in this one I want to concentrate on one particular church and five paintings inside of that church. This is the Franciscan Church (known as The Big Church) in the city of Shkodër, in the north-west of Albania, not far from the Montenegrin border.

Having their headquarters outside of the country, the Franciscans, in 1946, were forced to cease their activities in Albania – as were the Jesuits. In January 1947 a cache of arms and ammunition was found in their church in Shkodër and that led to the state clamping down hard on the order. The priests maintained these arms had been planted by the Albania security forces – but they would, wouldn’t they – and pleaded their innocence. The Franciscans resented this greatly and held that grudge for almost 50 years. However, those were times when efforts were being made by countries such as Britain and the US to do anything, and everything, they could to get a change of government in Tirana, one much more amenable to their political philosophy. We may have to wait another half a century before any material in the secret British Government archives might reveal more definite proof.

In the intervening period the church had been used as a cinema and auditorium but with the counter-revolution of 1990 they got their church back and a few years after that commissioned three new paintings – two more were to follow in 2012.

These are unlike any paintings I personally have seen in any church, of whatever variety of religion.

Here they represent that the gloves are off. They are a declaration of war against any society that has the temerity to challenge their superstition and their right to peddle such ideas to the young, confused, frightened and impressionable. Nowhere have I seen a clearer representation of the virulence of their hatred for socialism and, perhaps, is only comparable with the attitude of the Catholic Church and priests in Spain during the Spanish Civil War (1936-9) and earlier still during the height of the Spanish Inquisition in the 16th century. The arch-reactionary Karol Wotjyla would have loved them.

All the post-Communist, political/religious painters in this church have been painted by P Sheldija – I haven’t been able to find out anything about him. I can only assume that s/he is a local of Shkodër and that s/he’s still alive – at least s/he was in 2012. To the best of my knowledge I haven’t come across any more of his/her work outside this building.

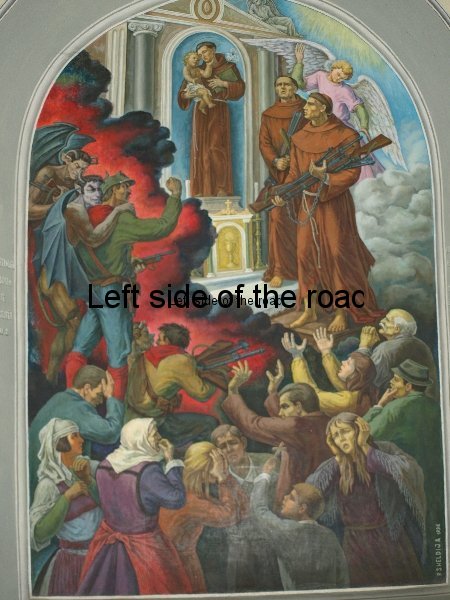

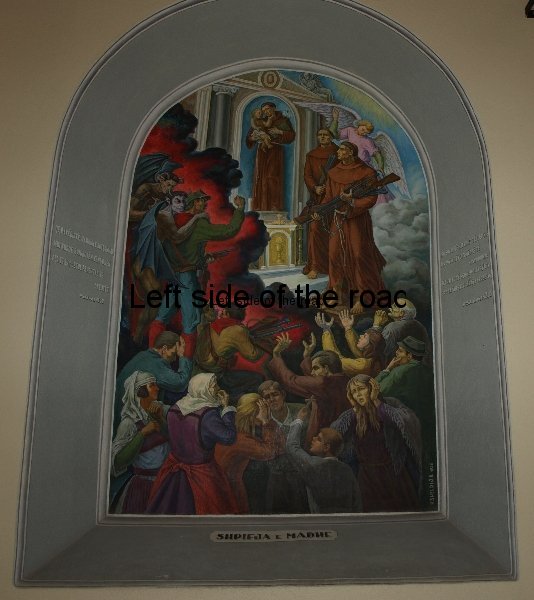

Who placed the arms in the Franciscan Church?

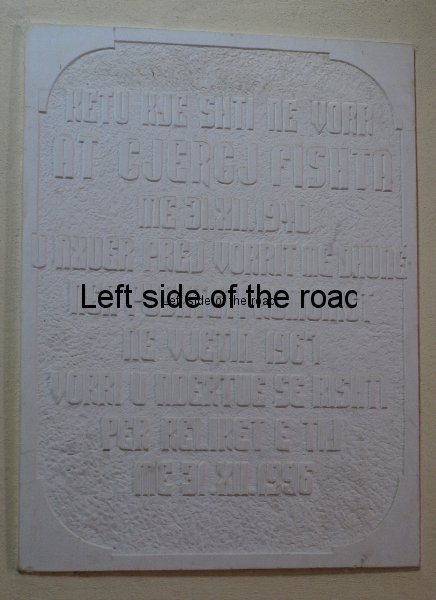

The first one is entitled ‘Shpifja e Madhe’, meaning the ‘Great Lie’ where the Franciscans maintain their innocence and is dated 1996.

What is interesting in this painting, and one of the aspects that unites the first three, is the influence of the Socialist Realist style in the depiction of the images. They depict ‘real’ people in ‘real’ situations. There are those who are obviously ‘good’ and those who are positively ‘evil’. Here there is no muddying of the waters. Communists = BAD, Franciscans = GOOD. And the ordinary people are the ones who suffer in this eternal battle.

Because it is an eternal battle and as the Communists are the Anti-Christ, they are literally the agents of the Devil. The Devil (or his disciples) are behind the Communists in both a literal and figurative sense. They are at the back of the Reds, talking into their ears, inciting them to attack the church and its loyal, faithful and non-violent servants. The Devils have horns, tails and bat like wings. The fires of Hell surround this group.

(We are encouraged to suspend disbelief here and forget the persecution that the Catholic Church perpetrated throughout the centuries, the deaths they precipitated, and the lack of sympathy for any ideas, or religions, which were not totally in accord with what was decreed in Rome. The ‘extirpation of idolatry’ was the term used in this context in South America following the arrival of the Spanish and entailed the physical destruction on any remnants of indigenous faith and beliefs.)

The principal Communist is aggressive, angry. His gun points at the Franciscans, his other fist raised in a threatening manner, a sneer on his face. Two of the Franciscans are in chains, forced to carry armfuls of guns. They are calm, stoical and have an angel of God looking over them. In a painting in a side chapel St Francis holds an infant Jesus in his arms.

At the bottom are the people. A mix of ages, social and ethnic backgrounds, gender and degrees of fear, shock, supplication, confusion displayed on their faces. They are begging, imploring that all this violence ceases.

(A Catholic raised friend who saw these paintings was shocked to see modern weapons depicted in a painting inside a religious building. I was a little surprised at that as I’ve seen an innumerable number of paintings and statues, world-wide, where St James the Moor-slayer is cutting off heads on all sides or where St Michael has been plunging a spear into the devil or his disciples.)

On either side of the painting are quotes from the Book of Psalms. The left hand side reads:

Qe, bakëqijtë harkun e shternguen

mbi kordë shigjetën vendosen

per t’i shigjetue fshehtas të drejtët.

This translates as:

For, lo, the wicked bend their bow,

they make ready their arrow upon the string,

that they might privily shoot at the upright in heart.

Psalm 11, v2

On the right hand side we have:

Per shkak të mjerimit të vorfenve

per shkak të klithmës së të ndryghunve

tashti do të ngrihem-thotë Zoti-e

do ta shpëtoj atë që e perbuzin.

Which means:

For the oppression of the poor,

for the sighing of the needy,

now will I arise, saith the LORD.

I will set him in safety from him that puffeth at him.

Psalm 12, v6 – but that’s not quite correct, at least in my Bible. The quote is from verse 5 and not verse 6.

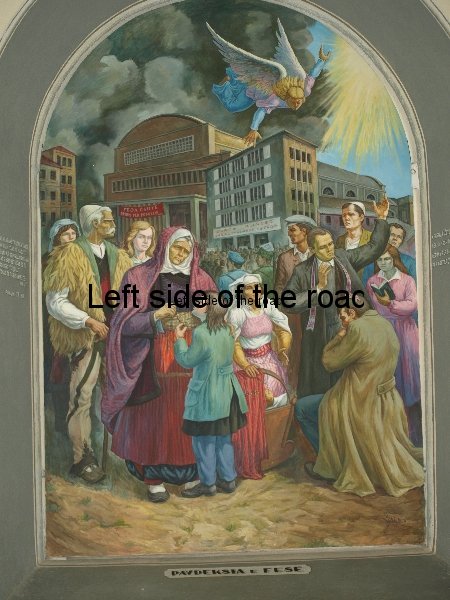

The atheists meet while the Catholics hold Mass

The second painting depicts an atheist, anti-religion meeting in the city of Skodër. On a banner is the famous phrase from Karl Marx – ‘Feja eshtë opium per popullin’, ‘religion is the opium of the people’. This banner is the red one, placed above the entrance of the Franciscan church when it had been converted into a community centre after discovery of the hidden arms cache and the punishment of the perpetrators. On the white banner the slogan is ‘Fight against religious ignorance’ – ‘Lufte kunder paragjykimeve fetare’.

This was also painted by Sheldija and is dated 1997 (signature and date in bottom right hand corner). It is above the title ‘Pavdeksia e fese’ which I think best translates as ‘religion is Immortal’ or ‘Religion can never die’.

The figures in the foreground have turned their backs on all this ‘nonsense’. Like in the previous painting they are a mix of ages and genders. Traditional as well as contemporary dress is depicted. The central figure here is a priest whose stole (the long, narrow sash a priest would wear when saying Mass and which he kisses before putting around his neck) is resting on the head of a bowed man, presumably a form of blessing.

An old woman looks tired and weary and in her hand is holding a rosary, which a young girl shares with her. Another woman also has a rosary in her hand but this one has the cross hanging just above the head of a baby in a cot. A young woman is reading from a Bible and in the background is the building in which the painting now resides, the Franciscan church.

This also has two quotes from the Book of Psalms on either side. On the left is:

Q hyj, e pushtuen paganët pronën tande,

e dhunuen tempullin tand të shejtë,

Jerusalemin e banë një grumbull rrenojash!

ua dhanë kufomat e sherbëtorëve të tu per ushqim shpendëve të qiellit,

mishin e shejtenve të tu bishave të malit.

This translates as:

O God, the heathen are come into thine inheritance;

thy holy temple have they defiled;

they have laid Jerusalem on heaps.

The dead bodies of thy servants have they given to be meat unto the fowls of the heaven,

the flesh of thy saints unto the beasts of the earth.

Psalm 79, verses 1 and 2.

On the right we have:

Kthehu, o Zot! deri kur kështu?

Deh, ki mëshirë për shërbëtorët e tu!

gëzona për ditët që na mundove,

për vjetët që i kaluem në mjerim.

Translated as:

Return, O LORD, how long?

And let it repent thee concerning thy servants.

O satisfy us early with thy mercy;

that we may rejoice and be glad all our days.

The carving says Psalm 90, verses 13-15 but it is actually verses 13 and 14. Perhaps the Albanian Bible numbers differently from mine.

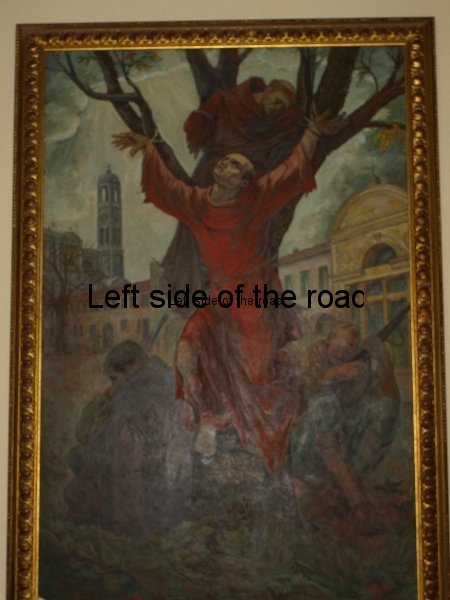

Crucifixion of Franciscan Friars

The third doesn’t have a title but is a reference to the Crucifixion. Also painted by Sheldija it’s dated (I think) 1997. Instead of Christ hanging on a cross we have two Franciscan friars being tortured by being tied to a tree. One of them looks up to heaven, his face a mixture of pain and serenity knowing that salvation awaits him.

Above him is another priest who seems to have been jammed into a fork of the branches although a rope comes from the branches to his left which presumably goes around his body to stop him falling. He has his eyes closed and is probably dead. It appears that his right arm has been cut off above the elbow as his sleeve is ragged and empty. What could be a tourniquet is around the upper arm. I’m not sure what is represented here.

On either side of the tree, sitting on the ground, are two Communists, both armed and one with the red star on his cap. They are possibly asleep, resting on their weapons. There’s obvious references to the crucifixion of Christ and the way it has been traditionally represented, with Roman soldiers taking the place of the Communist Partisans.

Although the idea is that the Franciscans suffered for their believes it seems to be bordering on heresy to imply that a mere mortal, Franciscan priest has the same authority as the (Son of) God. Even St Francis only went as far as to claim the stigmata.

In the background there’s a depiction of the very Franciscan church, with a distorted entrance facade on the right and the bell tower on the left.

Whilst the first two paintings are in alcoves along the length of the left hand side of the nave the painting of the Crucifixion is in an alcove to the left of the altar, up a few steps.

These were the modern paintings that were displayed in the church quite soon after its reconsecration and that remained the case until 2012 when two more paintings, also by the same painter, Sheldija, appeared on the right hand side of the nave. These both share and differ in style from those of the 1990s.

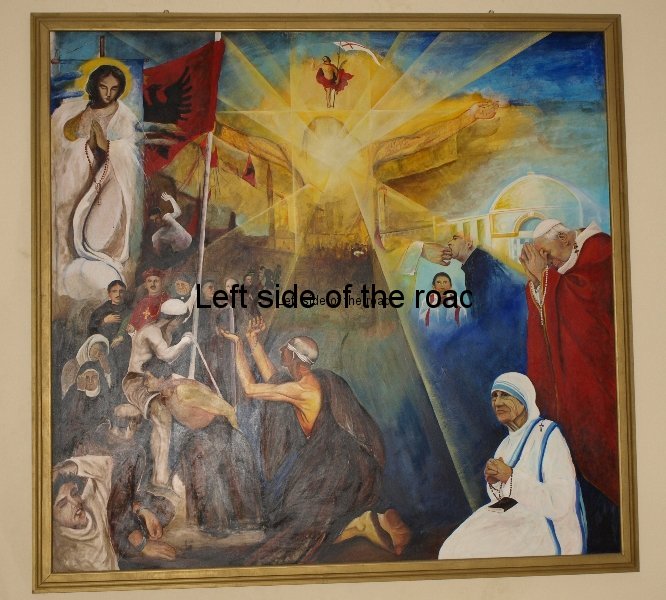

The first of the latest additions is entitled ‘Fe e dëshmueme me gjak’ which translates to something like ‘Bloody [Religious] Martyrdom’, martyrdom being very much a religious concept and therefore, perhaps, the word religious is slightly redundant.

Bloody Martyrdom

This follows very closely the style of the two paintings from the 1990s in that it is very much influenced by Socialist Realism but the image is as far from the principles of Socialist Realism as it is possible to get. In fact, this is quite a disturbing image and incorporates all those negative and pernicious aspects of capitalist, going-on fascist, society.

Whether it depicts an actual event I have been unable to ascertain, there’s no indication of such in the immediate vicinity of the painting, or it might just represent religious ‘persecution’ of the Franciscans in Albania’s past. If the previous paintings are anti-Communist this painting is anti-Islam and the devils are now Muslims in general.

As was the case with real Socialist realism imagery there was often a local reference in the painting or sculpture. Here we have reference to Rozafa Castle, which sits on a hill to the south of the present day city. The castle can be seen ion the top right hand corner.

At the base of the hill we have a small settlement of some kind where the only building which has suffered any damage is the small Christian church depicted on the left hand side of the panel. There are cracks in the wall, the roof is caving in and the small cross that would have been over the main entrance has been toppled over. The three or so homes in the picture seem to be intact.

Walking downhill from the building in the forefront (on the right) is a group of nine Albanians, all in traditional dress – seven men and two women. Outside of the church is another group of six Albanians – five men and one woman. What I don’t understand about these people is that they don’t display any emotion at all, unlike the very clear ‘distress’ shown by the Christians just a few metres away on the other side of the nave.

What I don’t understand here is what Sheldija is saying about them. Are they complicit in the ‘crime’ being committed, i.e., are they also Muslims and agree with the fate of the Franciscans or is it that they just don’t care? It’s difficult to tell as there’s no certainty about the date of the ‘event’.

Until the declaration of ‘Independence’ in 1912 the country had been dominated by the Ottoman Empire for centuries and although there might have been attempts by the Catholic Church to make an inroad in Albania (as they tried to do in all parts of the world as part of their imperial attitude towards religion) I can’t see them being able to actually build a church in secret, leading to its destruction when the Turks ‘discovered’ the transgression.

For the central image is the murder of two Franciscan friars by the Turks, represented by the five males in the right hand side foreground. We only get a fullish picture of one of them, the dark-skinned, bare-chested individual on the left of that group. He also holds the only weapon in view and that’s a long sword, blood covering its tip. The fact that there’s no firearms would seem to push this episode back a few hundred years – which I find even more confusing.

But as virtually all images of martyred Catholics I’ve seen in any part of the world the death has to be made even more cruel, more horrendous, more sadistic that it would have been in reality – this by a religious faith that has been destroying religious locations and the people holding non-Catholic faith for centuries.

What we see are two, sharpened wooden stakes that have been set into the ground and, presumably, the friars have been sat on the point so that their own weight forces the stake through their bodies – a favoured form of execution of the 13th century Mongol emperor. This seems to have been used by the Ottoman’s, even into the early 20th century, and the spike is called the Khazouk. If done by an expert the victim could live in agony for a matter of days. The fact that it was in occasional use by the Ottomans is accepted but I have been unable to find any documentary proof that in was used in Shkodër against Franciscans.

But in many ways that’s not what Sheldija is saying. He wants to make the point that the Franciscans were persecuted and the more hideous he can make this claim the better to attract his chosen audience – the ignorant and frightened of Albania who can’t make any sense of the society in which they live.

But as with some of his earlier works Sheldija dabbles in the heretical, equating the martyrdom of the Franciscans with the crucifixion of Christ, there being many references here to what have become, over the centuries, the traditional accouterments surrounding that supposed event.

The base of the Khazouk

Here is depicted the desecration of those items that are an integral part of the Catholic ritual: a crucifix laying in the grass; a chalice used for the Eucharist knocked over and spilling the wine (an allegory of the spilling of Christ’s blood); what looks like a discarded alb – the long, white vestment worn by a priest during a Catholic Mass; and a couple of books, one of which will be the Bible. The tip of the bloodied sword held by the Ottoman in the foreground is touching the cover of on of the books here stressing the idea of violence against the Christian church.

In the bottom right hand corner are the tools used to erect the khazouk; a mallet, three wooden stakes and a couple of stones used to maintain the khazouk vertical with the writhing of the victim.

What of the two victims of this martyrdom? As is always the case with Catholic martyrs not only are they shown with the instruments of their martyrdom they always have a serene look on their faces. And that’s the case here.

The friar on the left looks towards Heaven and holds a small wooden crucifix in his left hand, holding it close to his chest. His right hand hangs down at his side, pointing towards the ground. Behind his head protrudes the sharp, bloodied end of the spike and as he is still alive his own blood runs down the lower end of the stake and blood drips from his feet onto the alb.

The central, and presumably the more important, of the two has his arms outstretched on either side of his body, in emulation of a crucifixion. His right arm is bent slightly and he holds a small wooden crucifix towards the light of the Holy Ghost which emanates from the sky above. This is a common motif found in those paintings of Francis of Assisi as he ‘receives’ the stigmata – the wounds of Christ. As with his companion the blood covered spike appears a couple of feet above his head and his blood flows towards the ground along the wooden stake and from his bare feet.

One of the problems with this painting, in a society that is supposed to be ‘united’ now that Socialism has been dismantled, is that these images perpetuates the divisions within the country that are never far from the surface when religion is concerned.

In many Catholic churches in southern Europe you will encounter paintings, sculptures, of Sant Iago (St James) Matamorros – Moor Killer. The commissioning and the present day existence of these images can be put down to a less enlightened age but the fact that they are commissioned in the 21st century says a lot about the hypocrisy of the current wearer of the Triple Crown in Vatican City.

Most Albanian Muslims won’t be aware of such images – people with strong religious beliefs would never be seen dead in the ‘holy’ place of another faith – but they will tend to harden the attitudes of fundamentalist Catholics (of which there are many in Shkodër.

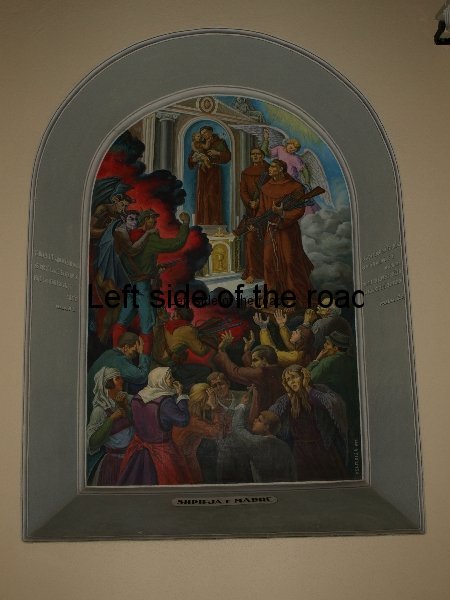

The other 2012 addition to the Franciscan Church’s decoration is entitled ‘Për fe e atdhe’ – ‘For God and Country’, and depicts (amongst others) the images of eight Franciscans who would later, at the end of 2016, be Beatified – plus one other who was obviously not considered to be saint material.

For God and Country

They were all charged with counter-revolutionary activity and died in the ten years following liberation. Many of them had been ordained and had worked in Fascist Italy and were openly ‘friends’ of the United States. When the US and Britain were actively attempting to subvert the young Socialist state; refusing to accept the revolutionary government and the Albanian Communist Party as the legitimate representatives of the people; sending flotillas of warships to intimidate the people who had suffered so much to rid their country of two fascist armies; and supporting the collaborating monarchist Fascists in neighbouring Greece in a Civil war against the working people and peasantry it was no wonder the state took a hard-line against any such counter-revolutionary activity.

It wasn’t as if the Roman Catholic Church had a spotless reputation when it came to popular movements. The Church was an open and fervent support of Franco, in Spain, against the legitimate government in the Civil war of 1936-39. Eugenio Pacelli (also known as Pius XII) was still in control of the Vatican after collaborating with both the Italian and German Fascists during the Second World War. He had no love of Socialism and supported the violent suppression of the attempts of building socialism in Bavaria (where he was Papal Nuncio) in 1919. And in Albania itself high ranks in the Catholic hierarchy opening consorted with the invading forces of both Italy and Germany.

Catholic priest in league with Hitlerites

So claims of ‘innocence’ by these priests have to be taken with a significant pinch of salt. The time of the ‘revolutionary priests’ of South America were a few decades into the future. All these priests had been brought up in an environment of Fascism and anti-Communism. they wouldn’t easily have dropped that stance and stood with the people.

We know the names of the Franciscans in the picture as their names are stitched into their clothing – as if their mothers didn’t want them to lose their cassocks. The image was painted four years before the decision about the ‘Blessed martyrs’ was taken and in 2012 the expectation must have been that Luigj Palio (the one at the top with the mustache) would have been among their number. He didn’t make the cut, however, for a reason I don’t know.

I don’t find this a particularly good painting – on any level. It lacks the bitterness and hatred of the other three in the building and also any lack of humour. By inter-twining the colours of the Papacy (yellow and white) with those of the Albanian stated (red and black) the artist seeks to give the impression of the close relationship with the present day capitalist country of Albania. However, the Catholics are very much a minority, their heartland being the area around the town of Shkodër itself.

The crown of thorns on the crucified Christ morphs into thick thorns bushes that line the inside of the arch at the top of the picture and then transform themselves into barbed wire around the crosses in the centre of the picture and creeping down to the church candles, symbolising what Sheldija considers to be persecution of religion.

As this is a Franciscan church an image of St Francis of Assisi is included, standing before the crucified Christ, his hands facing the viewer so that the ‘stigmata’ (the wounds of Christ) can be seen in the palms of his hands together with a spot of blood on the outside of his cassock on the right hand side.

One of the friars, Bernardin Palaj, standing on the right hand side of the image, holds a large green book in his hands, symbolising his ‘intellectual’ status.

An image of the very Franciscan church dominates the centre of the picture with the clock and bell tower rising up into the top right corner.

At the apex of the arch is an angel dressed in a purple dress, carrying a large bunch of branches. It’s difficult to make out exactly what they are, they don’t look like olive – which would be a symbol of peace (and also victory – after all the Catholic church has got back what it always wanted in Albania, that is a capitalist state). Another theory would be that the angel is bringing vegetation to cover the guns that the friars were to hide on the basement of the church.

Sheldija was obviously educated and trained under a Socialist system and the influence of Socialist realist style was still great in the 1990s, such that – apart from the content – it would have been stylistically indistinguishable from works by his contemporaries. However, like so many ‘intellectuals’ Sheldija sought to bite the hand that had fed him and used his skills to attack Socialism for the benefit of ignorance and obscurantism.

These have been the most political paintings I’ve seen in any of the churches I have visited in Albania. It’s not surprising that these should be in Shkodër as this was the Catholic heartland. In that city you don’t come across any Greek Orthodox churches, although there are at least three mosques.

At the same time Shkodër was also the place that the first Communist cells were established that later led to the foundation of the Communist Party of Albania (later the Party of Labour of Albania). Not surprising really, it’s in those locations of the greatest reaction that the seeds of revolt germinate and grow. Then and in the future!

Location:

The Franciscan church is in the narrow street Rruga At. Gjergji Fishta which passes to the left hand side of the Intesa Sanpaolo Bank at the bottom end of the pedestrianised street Rruga Kolë Idromeno in the centre of town, just beside the Big Mosque.

GPS:

N 42.067372

E 19.515415

DMS:

42° 4′ 2.5392″ N

19° 30′ 55.494′ E

More on Albania ……