Ushuaia – the capital of the Malvinas

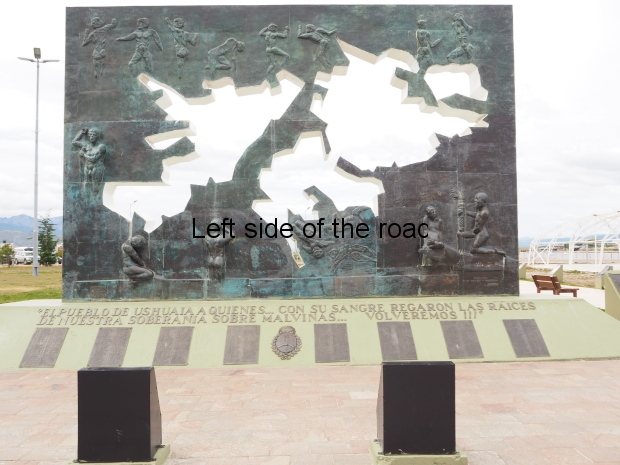

National Malvinas Monument – Ushuaia

The Monument to the Fallen in the Malvinas War in Ushuaia is the biggest I’ve seen so far and gleaning information from its constituent parts it has evolved over time and now comprises of 4 major and distinctive elements. It shouldn’t be a surprise that the monument in the most southerly town is the biggest as Ushuaia considers itself ‘the capital of the Malvinas’.

The orientation of the park is in the direction of the Beagle Channel and the outlet that will lead to the Atlantic and, eventually, the Malvinas.

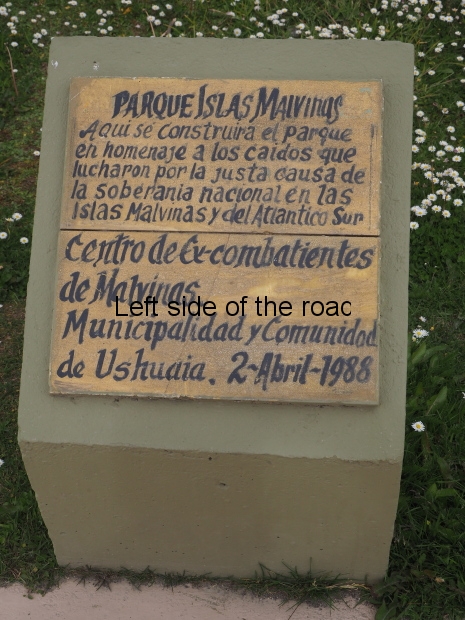

Malvinas Island Park

The Original Monument?

If I read things correctly the first stage in the development of the memorial was the establishment of a green area on the edge of the town centre, next to the water and the port of Ushuaia. The most simple, and almost hand made, sign in the area states:

Here has been constructed a park in homage to those who fell fighting for the just cause of national sovereignty for the Malvinas Islands and the South Atlantic Region.

The Malvinas Veterans Centre, the Municipality and the Community of Ushuaia.

2nd April 1988

(The 2nd April is the date of the beginning of the war.)

The park is a large, oval construction between the dual carriageway that serves traffic along the coast road.

The Principal Sculptural Monument

The Sculptural Monument

The principal artistic monument is a large, concrete rectangle that sits on a low plinth. This rectangle has a rough design of the two principal islands that make up the Malvinas group cut out of the concrete so – depending on the angle you look at it – you see either the mountains in the distance or the buildings along the river front.

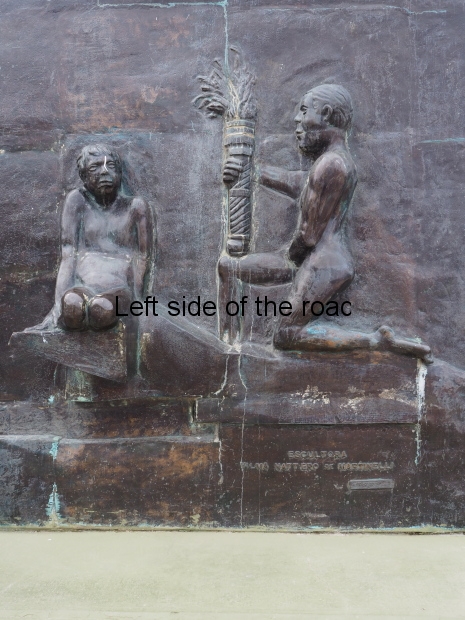

One side is unadorned and just painted green. On the other side is fixed a metal sculpture. As with previous attempts to interpret Argentinian Malvinas memorials I can’t work out what it is trying to say.

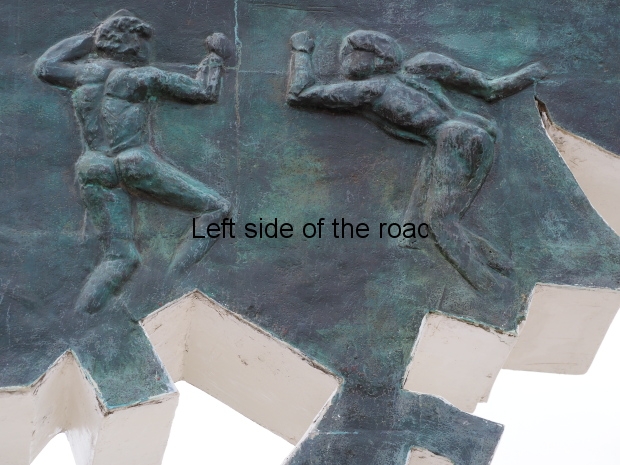

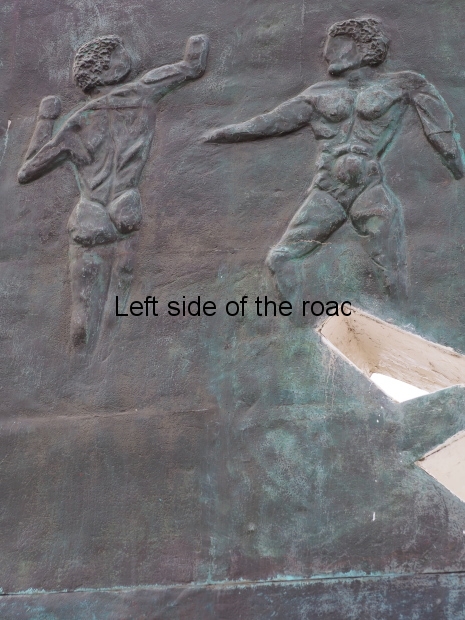

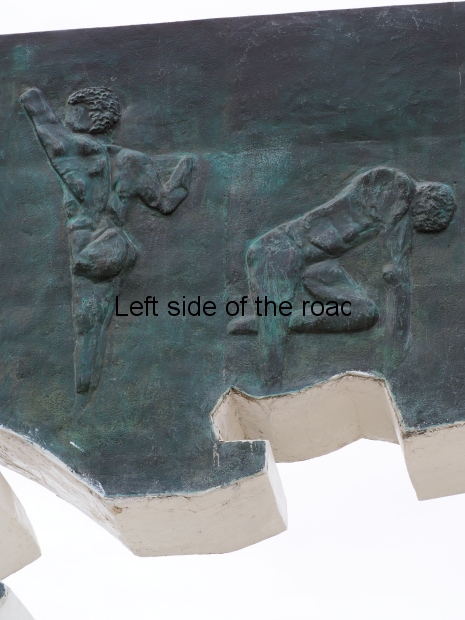

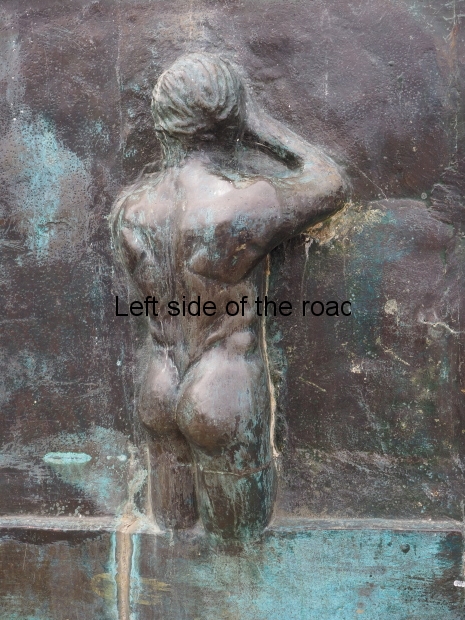

This sculpture is a mix of bas relief and almost whole body fixtures. All the figures are male and naked.

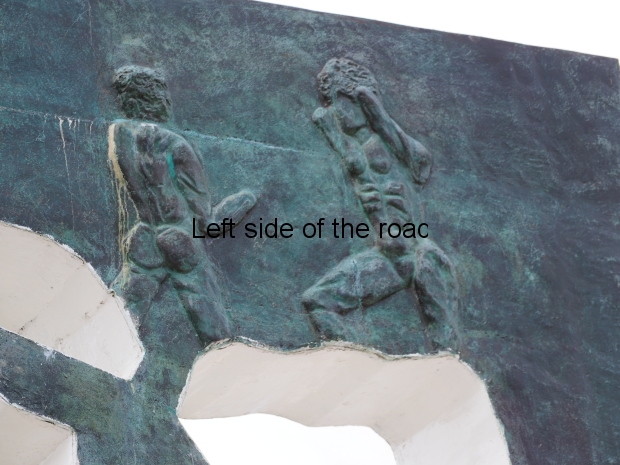

In the bottom right hand corner are two figures, One is kneeling, with his hands on the floor, and facing the viewer. To his left is another figure, showing a left profile and has the left knee on the ground and the other leg bent at 90º. Resting on this right knee is what I think is a flaming torch which he has gripped in his right hand in the middle. This seems to be some sort of offering to the other person of the pair but he doesn’t seem too interested as his head is only barely turned a few degrees towards the presenter of the homage. This could be a representation of an eternal flame.

Moving left there’s a group of naked prone figures – presumably dead – in bas relief. We don’t see all of the body and one of the figures is decapitated and many of the limbs are truncated.

Further left still we see the head, back and buttocks of another male. He is facing the wall so there’s no features. The right arm is raised and it looks like the palm of his hand is pressed against his forehead.

Moving further left is another figure, this time in profile – the right side showing. He is crouched down, only his toes touching the ground and he’s sitting on his ankles. His right arm is extended between his knees and his head is bowed. There is a feeling of despair from this figure. Even though the positioning of this figure would allow for some detail to be in the face here there is none. What we see is almost skeletal, with huge eye sockets. I’m not sure if he is wearing something on his head or whether it is the representation of short, wiry hair.

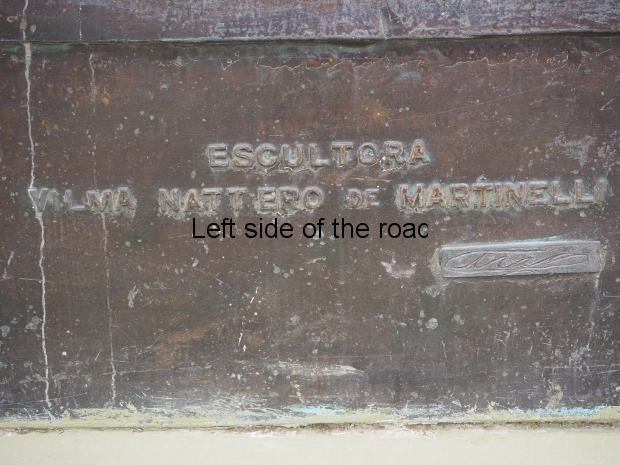

Finally, in the very bottom left, is a small plaque with the name of the foundry and the date of 1992. The name of the sculptor, Vilma Nattero de Martinella, is under the two kneeling figures on the bottom right. I’ve tried to find out more about her but have hit a brick wall. I thought that knowing a little bit about her background might have helped in translating her images but I had no luck.

All these elements are below the design of the islands.

In the space between the top of the islands and the top edge of the rectangle are four pairs of fighting figures in bas relief. There’s no detail in any of the faces and they all have various truncated limbs.

The only other figure on this face is that of a male nude, facing the viewer. He has his right arm raised and his right fist is clenched in a salute. His left arm is across his chest and he is holding something in his left hand but I don’t know what. His legs below the knees disappears into the concrete.

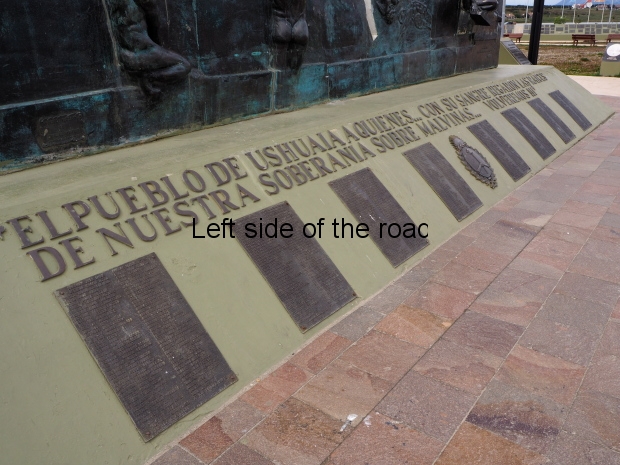

The plinth upon which this sculpture sits is angled out by about 45º and on this, in large bronze letters, are the words ‘El pueblo de Ushuaia a quienes ….. con su sangre regaron las raices de nuestra soberania sobre Malvinas …. Volveremos!!! (The people of Ushuaia to those who …. with their blood irrigate the roots of our sovereignty over the Malvinas …. We will return!!!)

These words sit above eight plaques which contain the names of the 649 Argentinian soldiers, sailors and airmen who lost their lives in the 1982 conflict.

In the centre of these eight plaques is the Argentinian National Coat of Arms.

Monument to the Heroes of the Belgrano

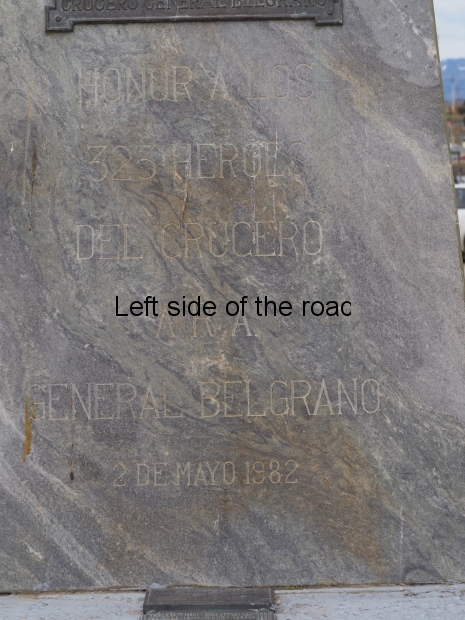

The Belgrano Monument

This is the most recent addition to the elements of the Memorial Park and has only been there for a few years. It sits to the left of the sculpture and just in front of the eternal flame.

This is in the design of a truncated pyramid and commemorates the 323 sailors who died when the light cruiser Belgrano was sunk by the British Navy’s nuclear-powered submarine Conqueror.

If there were chances of a negotiated resolution of the dispute over the Malvinas in the month after the Argentinian forces arrived on the Malvinas any avoidance of a conflict became impossible after the 2nd May 1982 with the sinking of this ship and the huge loss of life.

It’s a simple but effective monument, made so by the design of a symbol which encompasses many elements from the Argentinian side of the conflict.

Carved into the marble are the words ‘Honor a los 323 heroes del crucero ARA General Belgrano, 2 de Mayo 1982.’ (This translates as ‘Honour to the 323 Heroes of the Navy of the Republic of Argentina on the cruiser General Belgrano, 2nd May 1982.’)

Above these words is a brass plaque which refers to the ‘Friends of the Cruiser General Belgrano Association’. I assume they were the ones who raised the money for the memorial. (This is another reason why I think that the Malvinas memorials, in the main, throughout the country are not State sponsored.)

Above that plaque there’s an interesting design. Whether it is used elsewhere or not I wouldn’t know. It is likely that it was designed for this particular monument.

There’s a semi-circle made up of a sky blue line, a white line in the middle and then another sky blue line. This represents the colours of the Argentinian national flag. This ‘flag’ wraps around the bottom part of the Islas Malvinas. Across the centre of the circle described by the blue and white semi-circle is a bas relief of the starboard side of the cruiser Belgrano. Finally, as a background to the warship there’s the blazing Sun of May, the symbol that sits in the centre of the official Argentinian flag.

The Eternal Flame

The Eternal Flame

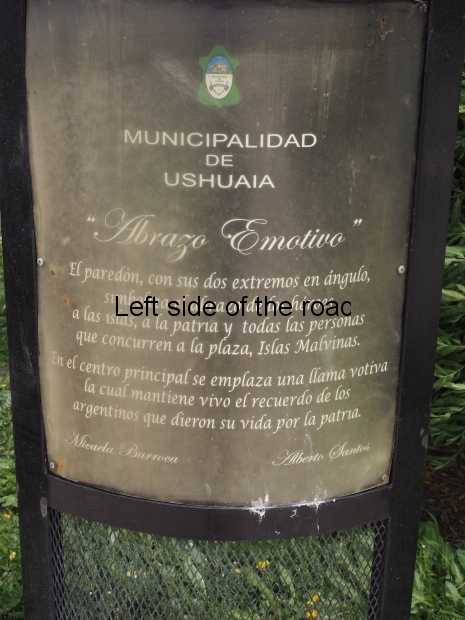

The next element must have been State sponsored – it’s too big and needs constant maintenance of the eternal flame to be a local affair. It was inaugurated on the 30th anniversary (of the disgusting and unnecessary war) in 2012.

It consists of a sunken pit which is lined by artificial grass (I don’t think the real thing thrives in the windy and salty environment of Tierra del Fuego). In the middle of this area there’s a square composed of white marble tiles. On these, from top to bottom, is inscribed in black lettering (obviously in Spanish) 2nd April 1982 – 2nd April 2012. Between these dates is the word ‘Malvinas’. Underneath the word Malvinas is a sketch of the islands themselves. Finally, using the Roman numerals XXX, we read 30th Anniversary.

On the same white marble square, at the back, is an eternal flame, in a circular metal container (painted white) on a combination of circular and square pedestals.

The whole area of the eternal flame is ‘protected’ by chains suspended from black metal pillars with golden ferrules.

Separated from the eternal flame pit by a walkway is a concave memorial wall on which is inscribed, in white letters, the same names of the 649 Argentinian dead as appear on the older monument described above.

Over these lists of names are the words ‘Para que todos los heroes custodian por siempre nuestra soberania’ – meaning ‘In order that all of our heroes take care of our sovereignty forever’.

The individuals who are attributed to the design and construction of this part of the monumental park are: Micaela C Barroca, Alberto R Santos and Cristian N Valencio.

On the left hand side of the eternal flame is a totally inappropriate – both in terms of design and content – ‘message’ from the Catholic Church. In a reddish brown arch, which really clashes with the black marble of the eternal flame and memorial wall, is a cheap printed image of a version of a floating in the air Virgin Mary (Our Lady of the Malvinas) over the cemetery for the Argentinian dead that is presently in the British occupied islands. This makes reference to the fact that her image has been vandalised in the Argentine cemetery in the Darwin (no seemingly Spanish name for this place).

To the left of that Catholic aspect (the first religious presence I’ve seen at any of the Malvinas monuments so far) is a long, low wall which contains the obligatory plaques of those who, over the years, want to declare their support for whatever cause the monument might be supporting.

There’s a couple from the Kirchners (the Peronistas) when they held the post of President, making a claim to their populist stance. Although one of them has slipped a little – the plaque I mean. I don’t know why these monuments aren’t better maintained. They seem to be established and then, more or less, ignored, until it will be politically expedient to clean them up again.

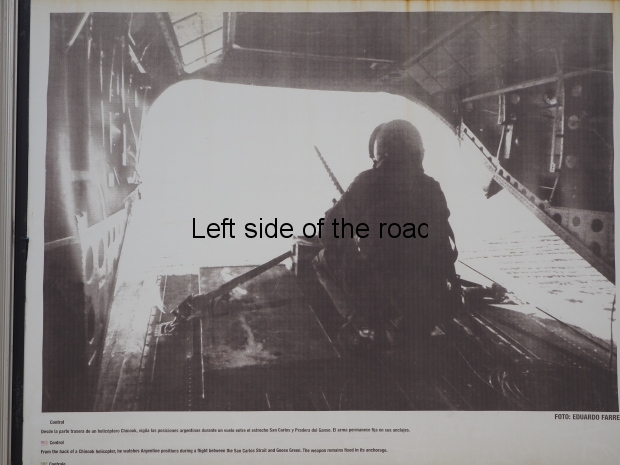

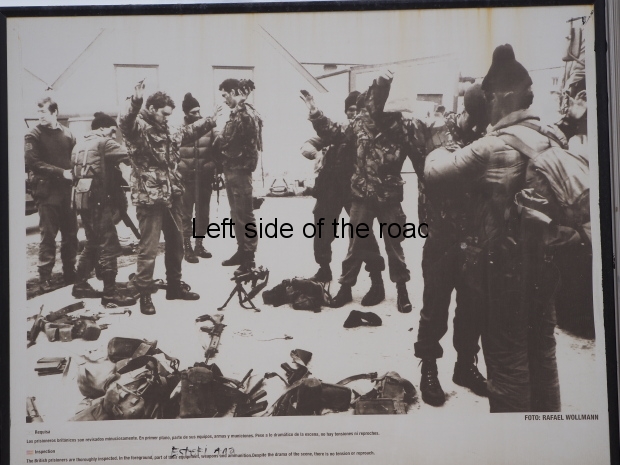

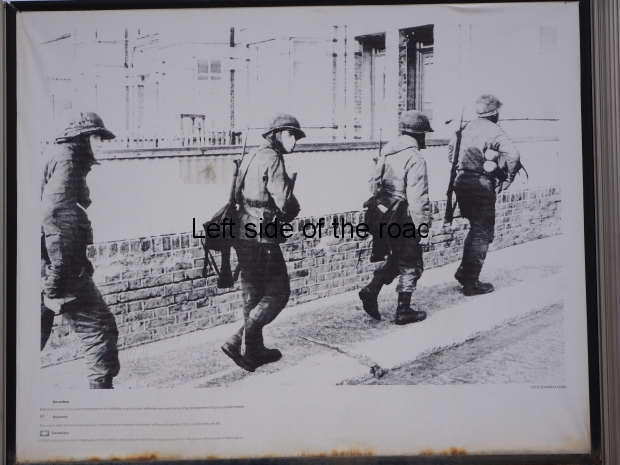

An open air photo exhibition

The Photographic Gallery

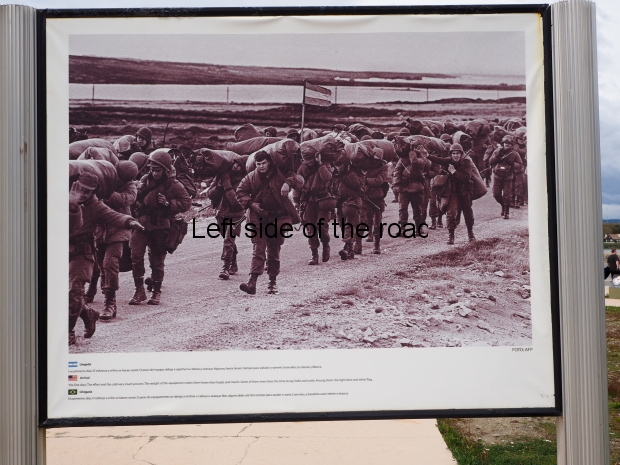

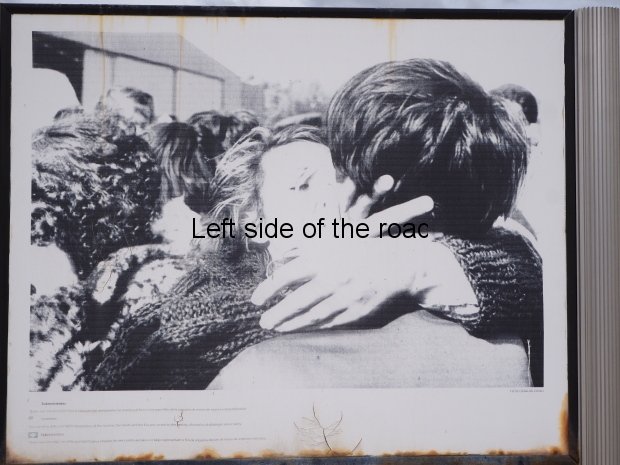

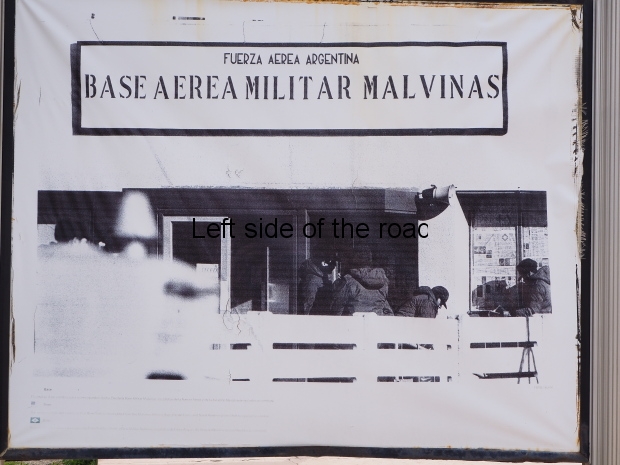

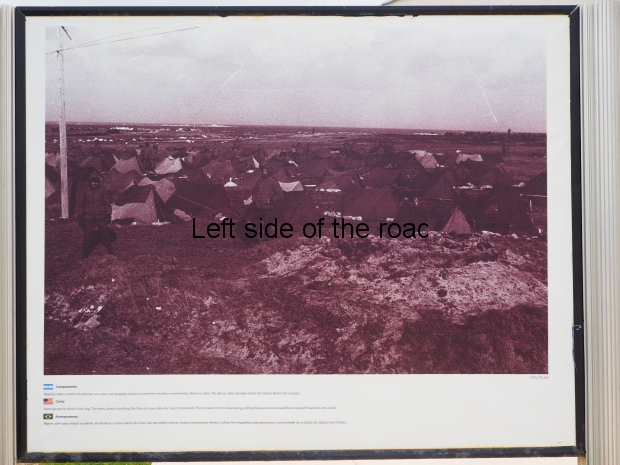

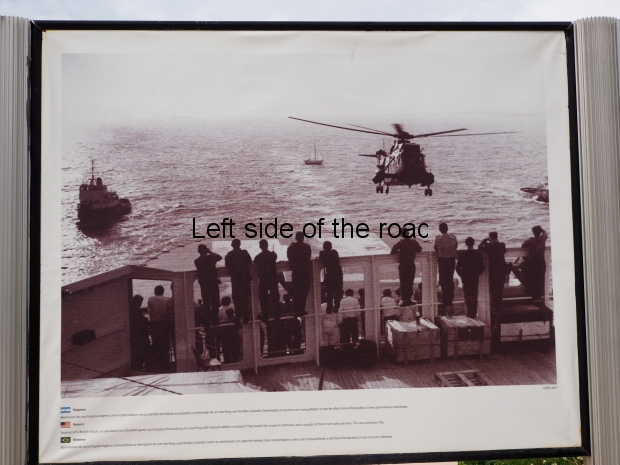

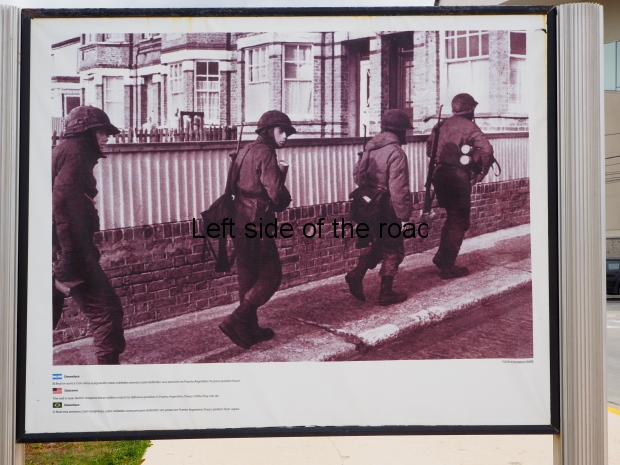

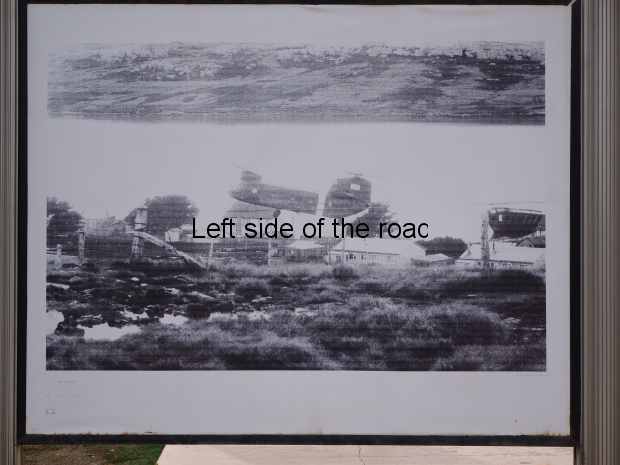

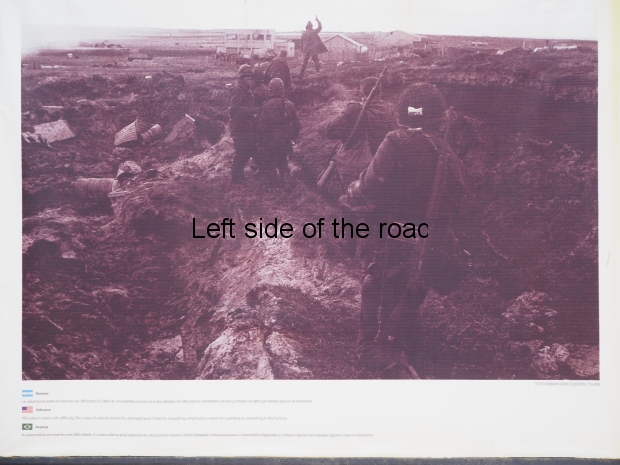

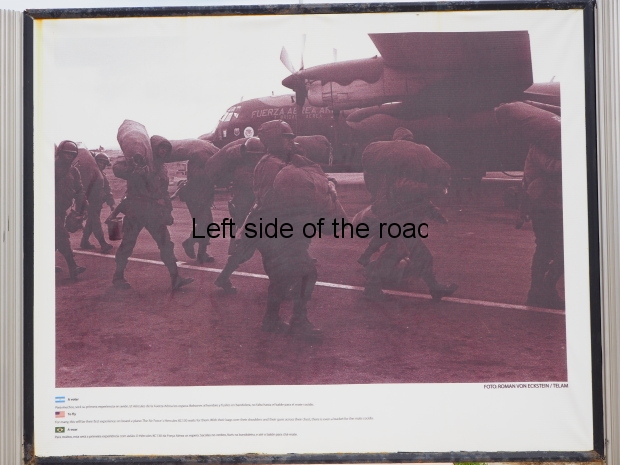

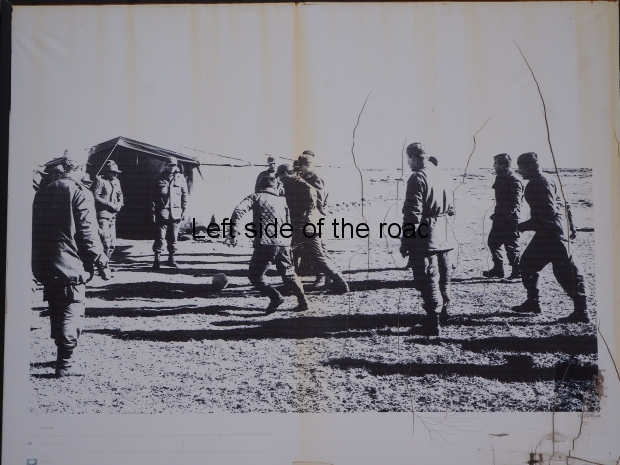

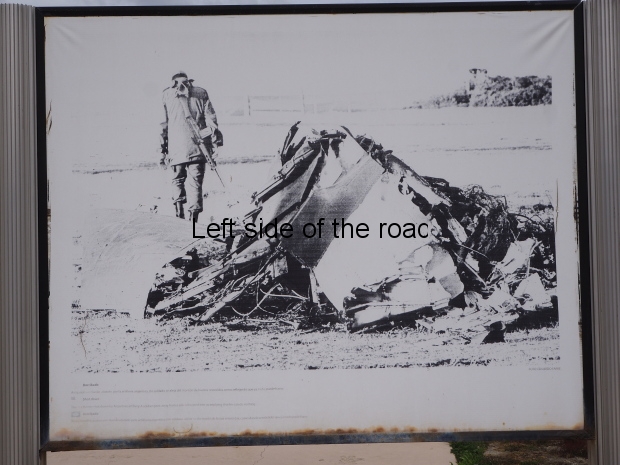

The fourth major element of the monumental park is a permanent photographic exhibition which is presented on 14, two-sided stands which are in an arc, on the pavement, on the eastern side of the park.

I have no problem with the concept of such a photographic record of the events of 1982 but the problem here is its execution. If you are going to tell a story in photographs from the time then a) you should tell a coherent story and keep images in a chronological order and b) you should make sure that the stands and the images contained in them can withstand the extremes of weather that are normal in this part of the world and don’t degrade.

The pictures weren’t particularly good examples of those produced at the time, on either side, but even reading the captions (which are in Spanish, English and Brazilian Portuguese) I wasn’t able to really follow any story. The fact that water had leaked under the perspex and were degrading the images from within and that the sun had also bleached many of them from without doesn’t help. So instead of presenting a short photographic telling of the events the viewer is left bemused, confused and annoyed – or at least this viewer was.

I’m not concerned about there being a propaganda aspect to the images – it’s what I would expect in Britain in any telling of the war – but there were images included which didn’t make sense. Why, for example, have a picture of British sailors brushing off the salt on the wings of a Sea Harrier? What is this telling us?

At the time of the war in 1982 the Argentines were in negotiations with the British about supplying the Argentine Air Force with Harrier jump jets. If Galtieri wasn’t such a prick there could have been a situation where British made Harriers would have been facing each other on both sides. That’s a story to tell, and should have been told in the Rio Gallegos Malvinas War Museum (but wasn’t), not trying to give the background to those who weren’t even alive at the time just some random pictures to look at.

The gallery contains all the photos on those stands, including (for some bizarre reason) a couple of duplicates, and in the order they appear on the street from left to right, so you can make up your own mind about how the story is being told. There are 28 photos in total.

A song and a pledge

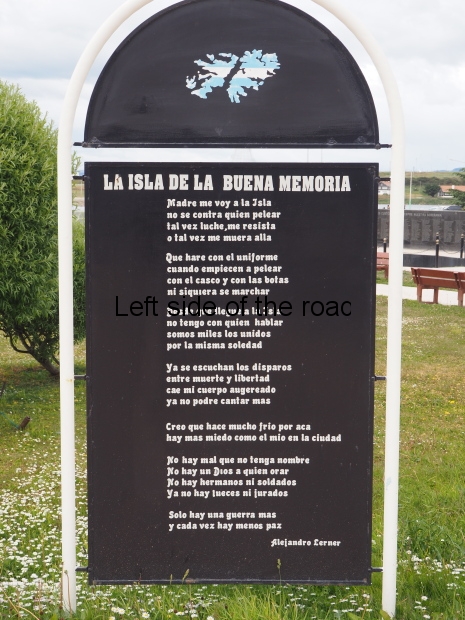

There’s an arch over the western end of the park and flanking this arch are two boards, one with the (partial) lyrics of a song by an Argentinian popular singer song-writer, the other by Pablo B Rodriquez (about whom I can find no information).

The Pledge

Volver a Malvinas

Sin odios ni recores, con coraje, en alto la bandera de la Patria llegaremos con firmeza a nuestra islas que usaparon un día los piratas.

Nuestra enseña está latiendo al viento allí donde ayer la metralla, segando la vida a tantos jóvenes que el camino de regreso nos señala.

Nuestros muertos queridos, a Malvinas desde sus tumbas mantienen custodiada …. por ellos voveremos, por su ejemplo, por el sacrificio de su sangre derramada.

El cielo que tambien es Argentino ya la izó la bandera azul y blanco.

Pablo B Rodriquez

My translation:

Return to Malvinas

Without hatred or resentment, with courage, with the flag of the Fatherland flying high we will arrive steadfast on our islands that one day the pirates stole from us.

Our school is beating in the wind where yesterday the shrapnel, which took the lives of so many young people will show us the way back.

Our beloved dead, from their graves keep guard on the Malvinas … for them we will return, by their example, for the sacrifice of their shed blood.

The sky is also Argentine and hoists the blue and white flag.

Pablo B Rodriquez

The song

La isla de la buena memoria

The island of good memories

Madre, me voy a la isla,

no se contra quién pelear;

tal vez luche o me resista,

o tal vez me muera allá.

Mother, I’m going to the island, I don’t know who I will fight;

I might fight or resist, or I might die there.

Qué haré con el uniforme

cuando empiece a pelear,

con el casco y con las botas,

ni siquiera sé marchar.

What to do with the uniform when you start to fight,

With the helmet and boots, I can not even go

Desde que llegué a la isla

no tengo con quién hablar.

Somos miles los unidos

por la misma soledad.

Since I arrived on the island I don’t have anyone to speak to.

We are thousands united in the same solitude

Ya se escuchan los disparos

entre muerte y libertad,

cae mi cuerpo agujereado,

ya no podré cantar más.

Already can be heard the shots between death and liberty,

my pierced body falls, now I can’t sing any more.

Creo que hace mucho frío por allá;

hay más miedos como el mío en la ciudad.

I think it’s very cold there;

There are more fears like mine in the city.

No hay mal que no tenga nombre,

no hay un Dios a quien orar,

no hay hermanos ni soldados,

ya no hay jueces ni jurados,

There’s no evil that doesn’t have a name, there’s no God to pray to,

there aren’t brothers nor soldiers, now there are no judges and juries,

sólo hay una guerra más …

y cada vez hay menos paz.

There’s only another war …. and each time less peace

Alejandro Lerner – singer, song-writer

The song can be listened to here. I must admit it didn’t do a lot for me.

Location

It’s the big square at the far end (Block 1300) of Avenida Maipu, just opposite the huge Casino.

GPS

S 54.81021

W 68.31581