Chapter 9 – Keld to Reeth

The day by the river

Although one of the cheapest of the places I have stayed in so far the so-called bunkhouse at Keld was probably the most luxurious, more by chance than anything else. What is called the bunkhouse is basically an annex, attached to the main farm building, that’s been converted into a separate two storey house. In 2 of the 3 bedrooms there are bunks which means that it can be used as a place for a self-contained group or for individuals such as myself. On the ground floor there’s a kitchen cum dining room cum lounge. What made the place luxurious was that I was there by myself. (Well, not exactly. A couple came after I had gone to bed and occupied the downstairs bedroom but I had the place to myself when I was moving around.)

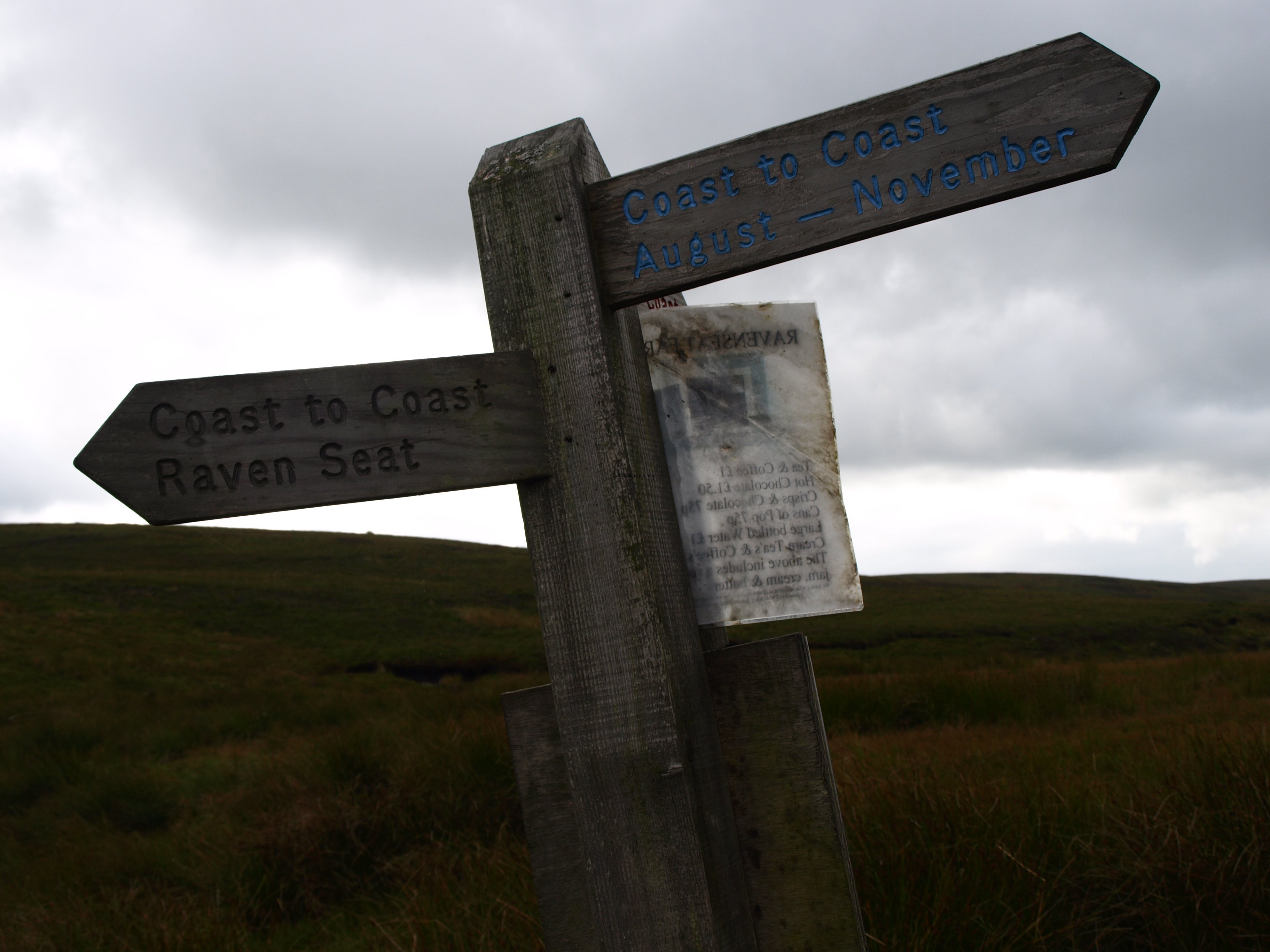

If it was good to get an early finish the day before I gave myself an added bonus with a late start today – not leaving until 10.20, the latest start on the whole of the trip. The walk to Reeth was only 11 miles or so and I had also decided to take the route that would follow a stretch of the River Swale before going up to the moors again before descending down to Reeth. It was a grey day, again, but at least the rain, more like persistent drizzle, that had fallen just before it got dark hadn’t remained and it didn’t look like the weather would turn for the worse. If I had gone on the higher route there would have been sections of boggy land where I would have been up to my ankles in mud and the views would have been non-existent so I thought there was little point of the additional effort. And anyway, going the lower route I would pass through, or close to, a couple of small hamlets and thought of having a midday pint in one of the pubs.

From the table I was sitting at for breakfast I was looking out over a small waterfall behind the house and across from that 3 or 4 pheasants were searching for food. I had come across the occasional game bird over the previous couple of days, but only individuals, and would start to see many more from now on. The route was starting to enter the Yorkshire moors that were specifically managed for the hunting of both pheasant and grouse.

I don’t think I’d got so close to a grouse before this expedition. They’re not very good flyers and the first one was ‘trapped’ as I came across it along a lane, just at the place there was a gate and when there was a wall on either side of the lane. The only escape route would have been the direction I had come but the grouse’s instinct is to fly away from perceived danger, not towards it even if that was the best escape route. So I don’t think they are the most intelligent of birds (and probably accounts why the not most intelligent of people can shoot so many of them). They panic as they run around but I was able to get a few, reasonably close, pictures of them. These were the red grouse.

The place I was staying was to the west of Keld, just before entering the village proper, and due to the drizzle, and the fact that I was quite warm and comfortable sitting alone in the house, I decided against going to the local pub. There might well have been a few people I had met on previous days there but laziness got the better of me. That worked out well as the pub was a lot further than I was given to expect so had no regrets when I realised the effort that would have been needed the previous night – I’m doing enough walking without adding any additional miles.

It seems that each part of the country has its peculiarities and little traps to catch out the unwary walker, and in Yorkshire that local joke are the stiles cum gates that are built into the dry stone walls. These are very narrow openings in the walls that often have a gate on a tight spring at one side and a flat, upright stone that prevents any sizeable animal from getting through. Not always, but very often, there are a couple of stone steps on either side of the opening so there’s a certain skill and dexterity to negotiate these obstacles. They tend to be narrower at the bottom, opening out higher up, as they would have been built so that there’s enough room for the feet but then allowing that most people are normally fatter at the waist. But when I say ‘room for the feet’ I really mean room for a foot, as few of these allow you to stand with your feet side by side.

So you have to imagine the situation. You arrive at one of these stiles and open the gate towards you as you step up to the gap in the wall. There’s only enough room for one foot so you have one leg trailing as you use one hand to keep hold of the wall and the other to keep the gate from swinging back and propelling you into space. Now you have a problem. What do you move first? Probably the best bet is to shuffle forward on the foot in the gap until you get to a situation where you can place both feet on the wall behind each other. Now it may be possible to release the gate BUT you have to bear in mind that you have a rucksack which effectively makes your body much bigger. If successful the weight of the gate and its spring presses against the rucksack but not in such a way that it pushes you forward. Now you have the use of two hands. Using them to lift your body you tentatively move forward so that you can squeeze through the narrow gap caused by the flat, upright stone. Then with a supreme effort you launch yourself forward, step through the gap on to the step on the other side, drag your bag through behind you, scraping the sides of the gap as you do so and you are through. If lucky in one piece.

I’m not that big and my rucksack, although big enough for me, not as large as someone who might be camping. How some other people get through is beyond me, very much like contracting the body as an octopus does to go through impossibly small openings.

Once you’ve got though and congratulated yourself on your self-preservation you look up and see there’s another one less than 20 metres away and there were a lot on this walk, through the fields and meadows alongside the River Swale.

After having seen the pathetic sight of the unfortunate rabbit the day before perhaps it was fitting that this morning I passed by a huge rabbit warren indicating that the rabbit population, in general, in the area seemed to be healthy enough. I have to take the guide-book writer’s word that it was rabbits as the entrance tunnels seemed very big to me but then I must admit I’m not really an expert on native British mammal’s underground construction sites. Also it seemed too low, the land sloped away quite quickly at this point to some hills behind, and too close to the river in the event of a flood – but then, again, I assume the rabbits know more what they’re doing than me.

The idea of a pub crawl fell apart quite quickly. The first opportunity would have meant a slight diversion to the hamlet of Muker. There’s supposed to be a pub there but I decided against the diversion for a couple of reasons. It was still relatively early. Although I had left later than usual I was at this point before midday and there was no guarantee that the pub would have been open at that time during this time of year, not quite the closed season but definitely on the point of closing down.

This is one of the negative consequences of the changes in the pub licensing hours that happened way back in the late 90s. When pubs had fixed opening times you could guarantee that a pub would be open during certain times of the day. If my memory serves me right they had to, as part of their license, coming as it did from the days when pubs were obliged to provide a service to travellers. I welcomed the change in the opening hours but learnt very quickly that this change was a doubled-edged sword and what we gained from the change was far outweighed by what we lost.

Stay behind pubs lost out as their regular customers would remain local rather than travel to a place they knew would stay open illegally. That meant that after years of knowing where someone might be at a particular time, especially on a Saturday, with the changes you couldn’t. One of the consequences of this was that when the pubs could more or less chose their opening hours that the pubs that used to stay open all afternoon stopped doing so as it wasn’t worth the effort if they didn’t have a sufficient number of people who were prepared to ‘break the law’. As things have developed in subsequent years it means that if you turn up at a relatively isolated country pub you have no idea whether it will be open or not.

A lesson in being careful what you wish for.

So I left out Muker and thought of the pint I would have in Gunnerside, another that the guide-book had recommended. On arriving at this village I found the pub shut, but not for the reason above but for the fact that it couldn’t pay its way and had closed some time ago, as have so many throughout the country. Among other things this exposes the limitations of guide books. However well there is an attempt to keep information up to date things can change very quickly and if you are going to actually depend upon such information it would be best to make a telephone call to confirm that the business was still running. This would be highly recommended if your plan was not to just drink but eat in such a place. Turning up on spec would not be a good idea in the present (and foreseeable) economic climate. I was told that this pub had been closed for some time, although looking through the windows it didn’t seem like that long ago.

But this made me think of the plight of pubs along routes such as the Coast to Coast. During the course of the year thousands of people must do this walk. Now, not every one of them will be a drinker but it is not unknown for alcohol to be associated with walking and those pubs that provide food will also be attracting more custom. But now the struggling pubs have a new problem in the fact that the infrastructure of accommodation that has built up to service this growing number of visitors is actually hammering another nail in the coffin of the ‘local’.

At one time British B+Bs were notorious, not for what they offered but for what they didn’t. They didn’t offer en suite; they didn’t offer all day access; they didn’t offer a friendly and welcoming atmosphere; they didn’t offer a home from home more a remand home from home; and they didn’t offer alcohol. Now, many things have changed, including the last. More and more places, with very limited accommodation, I’m not necessarily talking about anything that borders on a hotel, have acquired a drinks license and that is bound to have an impact on the pubs in these small country villages.

In the long distant past when I did any of these long distance walks, or even a strenuous day in the hills, it was almost obligatory to end the evening in the pub. Now you can get your alcohol fix without leaving your B+B, or even camping site. I’ve done this myself in a few places I’ve stayed in so far, even those places where there was a choice. To the best of my knowledge all hostels of the YHA are now licensed, at least I haven’t come across one that wasn’t, so that means even in the most isolated locations you don’t need to leave the front door for the fix. When I was in Shap, after a long and tiring day I wanted a drink but when I knew they served in the place I was staying any inclination to go out and walk again before the next morning just evaporated away. The same in Keld, even though I thought the pub was closer than it really was. And I’m sure I’m not the only one that has followed that pattern.

If the pubs could have survived with the walkers coming in during the day time as they passed through a village and then had those staying locally bolstering the takings in the evening they are now finding that one of their income strands is disappearing. If there might be opposition from pubs to the granting of these licenses when the pub exists the argument of the B+Bs gets stronger if the pub should close. In those circumstances, unless there is a local community group prepared to go through all the hassle of re-opening the local as a community run pub, as was the case in Ennerdale Bridge, then that village will never have a pub again. So even an increase in tourism and overnight visitors is not, necessarily, a recipe for success for the unique British institution. Things don’t look too promising in this region of the country and I came across a similar situation in some villages when I did the Hadrian’s Wall walk a couple of years ago.

Today was probably the day I reached my psychological low.

There were a couple of reasons for that.

Today is my 8th walking day and I’ve only just passed the half way point. That means there’s still a lot of miles to go and in only 5 days. So even if the final stages don’t have any major ascents during the course of the day each one will be long. That’s a problem but not the most serious one.

That is the rucksack. I’ve never liked carrying a big load and when you have to pick it up and then walk a not inconsiderable number of miles my enthusiasm wanes considerably. It’s not heavy heavy, roughly 12,837 grammes (that’s 28 lb 4.8119 oz, more or less). But today it felt uncomfortable from the off and not just becoming so towards the end of the day. I’m glad I got a more modern bag as my old one was inadequate for the Hadrian’s Wall walk and would have been totally unsuitable for the Coast to Coast. The new bags adapt to each individual’s size and preferences. Carrying it for a couple of days, as I did when I made my short expedition to the Lake District earlier in the year, was no problem at all. It starts to become a problem when it seems that you will have to carry it forever.

I haven’t been carrying the heaviest bag of those I seen along my way so far but certainly heavier than most. Of those I’ve got to know slightly most have their main luggage picked up each morning and dropped off at their next nights accommodation so they carry a minimum needed for a day’s walk in the mountains. A few companies have developed to cater for this wish and they probably make a nice enough profit from it as they are far from cheap. I didn’t even consider investigating these companies but, I must admit, there were a few minutes during the course of today when I wondered if that might not have been the best choice.

I’d pared things to the bone and considered that I had brought what was necessary to cope with any adverse weather conditions I might encounter at this time of year but it was still more than I would have liked. (But then I would have liked to have carried virtually nothing as my preferred walking environment is Mediterranean spring or autumn, or even the summer, which requires no wet/cold weather gear or, at least, it didn’t until climate change also made the weather uncertain in that part of the world as well.) The other issue is that the computer and camera (together with all the bits and pieces needed to keep them operational) weighed in at 7 lb 7.8692 oz (or 3399 grammes), just over a quarter of the weight.

Although these thoughts did have a tendency of making the day a little harder and longer than it actually was (and the lack of an alcohol anaesthetic due to closed pubs unavailable to mitigate such feelings and thoughts) the weather did improve as the day wore on and there was pleasant sunshine as I again came to walk along close to the River Swale on approaching the village of Reeth, my overnight stop.

And the next day was the second scheduled rest day!

So at 16.10 on Thursday 26th September it was 109 miles down and 91 to go

Now over the half way mark but it’s taken 8 walking days to get there – however the distances should start to roll by as length of walks becomes more pertinent than height (at least I hope so).

Practical Information:

Accommodation:

Black Bull Hotel, £40 for a single B+B. Surprised when I was taken to a room, overlooking the green in the centre of the village, with a big, double, four-poster bed. And another surprise when I looked in the bathroom, no shower but a big bath. So the first treat in Reeth was a long soak in deep, hot water (with bubbles provided by the hand soap lotion). It’s important when you arrive at a place with baths (rather than showers) that you take advantage of the hot water when it exists. Only the most modern hotels and guest houses will have such powerful boilers they can provide hot water on demand when so many people arrive at the same time. I heard members of the group (of 9 I’ve come across a few times and who are now staying at the same place) complaining about the lack of hot water but if your priority after a days walking is a cup of tea – which I know is the case with some – then you have to get used to cold showers.

This is another quaint old building where the floors are uneven, I have to sit still in bed otherwise I’ll spill my tea on the bedside table; the door is a strange shaped piece of wood which fits the doorway – just; and like the place in Shap, even though the walls are thick you can hear voices from other rooms. There’s a certain smell about these buildings which is quite unique. It’s not of dirt but of a kind of ‘lived in’ smell, not the sterile, clinical atmosphere that seems to pervade modern housing – even the likes of my flat which is in a building close to a couple of hundred years old. I suppose the change came when they decided that the straight line was important in house construction.

But, now I’m here, it’s not as good an idea that I’m in the YHA for the second night. That’s a walk of about a kilometre away but, at least, it’s in the right direction for when I start to walk on Saturday. I don’t get the full benefit of a day off having to get out of the room in the morning and pack all my things. But after a late(ish) breakfast I plan to sit in the bar and use the computer until mid afternoon and then head up to the YHA.

Free wifi in the bar area only – blackbull1680 (due to the structure of the building and the fact that it dates back more than 300 years).