Monument to the Partisan – Tirana

More on Albania …..

Monument to the Partisan – Tirana

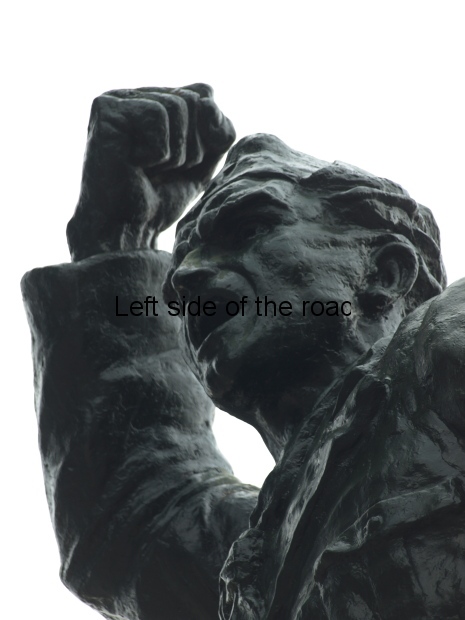

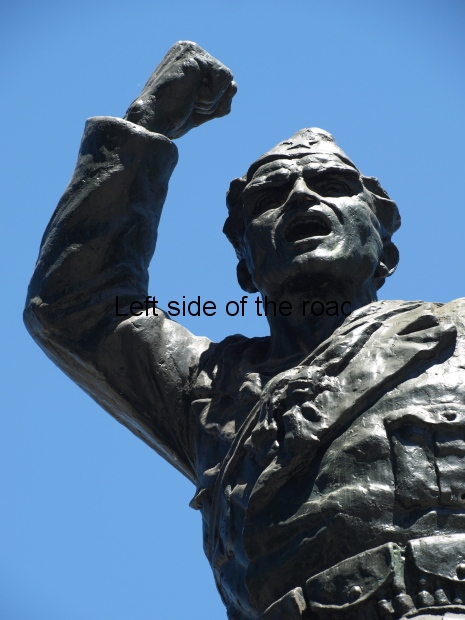

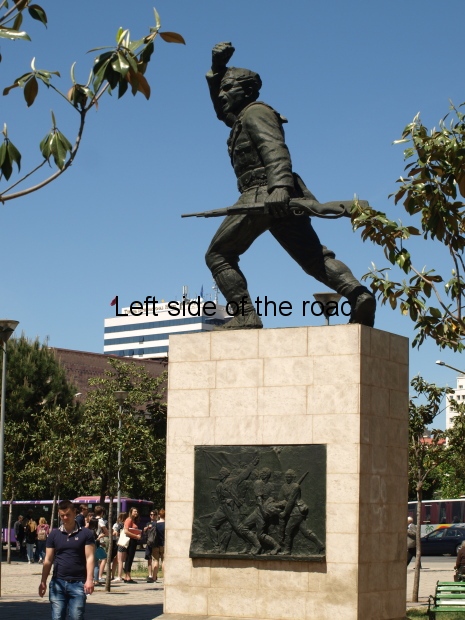

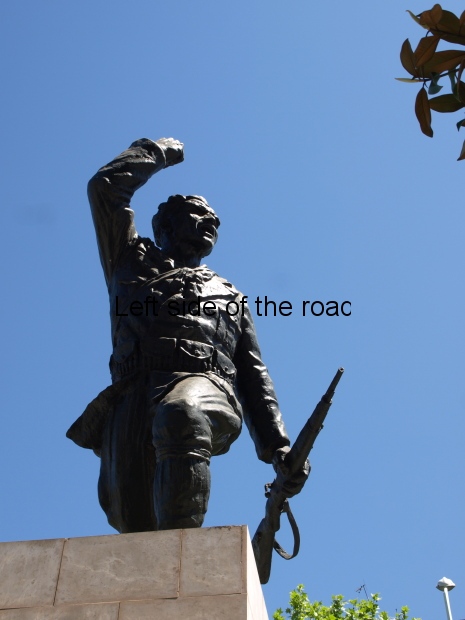

The ‘Monument to the Partisan’, the work of sculptor Andrea Mano, was created in 1949. It is one of the oldest lapidars in Albania created in the Socialist period and is the monument that has survived (relatively undamaged) the longest in its original location.

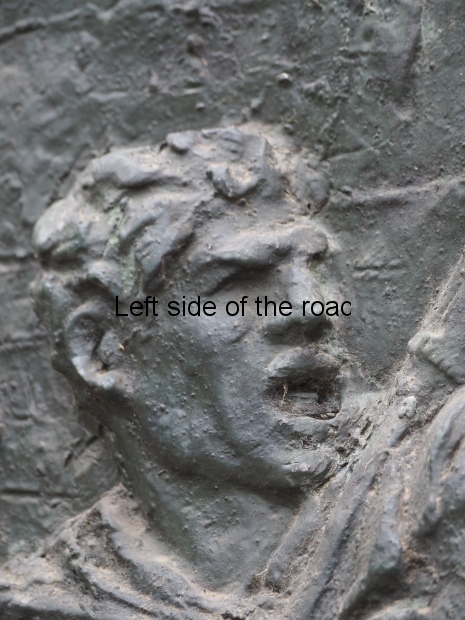

The monument consists of a larger than life size figure of a Communist Partisan in full uniform and fully armed. He’s depicted running forward, the element of speed being indicated by the right edge of his jacket flapping in the wind. In his left hand he carries a rifle (his hand is gripped around the barrel in front of the trigger mechanism) but his arm is fully extended downwards so it’s not ready to be used – this rush of his is not to join the battle but to join the celebration of the victory.

His right arm is raised above his head, slightly bent so his hand is pointing behind him but the fist is clenched. This is a visual representation of ‘We have done it’, and a sight that is quite common in present day sporting events. His mouth is wide open and so we know he is shouting but to whom and what we do not know. However, we are given a clue to the event by the inscription – and also the actual location of the statue.

For it was in this area of Tirana, on 17th November 1944, where the last remnants of the Nazi invaders were either killed or surrendered to the Partisan army.

Bukurosh Sejdini – 17 November 1944 – 1957

He’s not a particularly young man and might be an officer, his uniform is quite smart and over his left shoulder is a strap to which is attached a satchel – which rests on his right hip. However, he doesn’t have a pistol – a normal sign of an officer. (It might be worth commenting here that although the Partisan force was very much a Communist organisation, organised along Communist lines, there still existed a hierarchy of officers and ‘men’ – although a huge percentage of the ‘men’ were female.) On a belt around his waist are a number of pouches with reserve ammunition.

It’s difficult to see (without climbing up the plinth) exactly what he has on his feet but it appears to be the more traditional Albanian footwear than an otherwise more usual heavy boot of the majority of the armies fighting in the Second World War.

However, what we can be certain of is his political allegiance. On the front of his cap can be seen the star and around his neck a scarf, both of which would have been red in actuality. This partisan is a Communist. Perhaps, as his political status is clear – and would have been to all who knew this statue at the time of the reactionary uprising of 1990 – I’m slightly surprised he didn’t suffer any serious vandalism.

The statue of Enver Hoxha, which was pulled down on 20th February 1991, was only a few minutes walk from where the Partisan still stands and it wouldn’t have been too much of a surprise if some neo-fascist (having pulled itself from its hiding hole) hadn’t tried to damage a representation of Communist success. At the same time all the failings in Albanian society were being placed on Enver’s shoulders and personalising matters was a useful tactic for both the reactionaries and those in the higher leadership of the Party of Labour of Albania.

I’m afraid I’m not a big fan of this statue – and didn’t really like it when I first saw it just under nine years ago. At the time I thought he looked too angry – but not in a good way. That was before I fully realised what the statue represented – which was the liberation of Tirana and the soon to be victory of the Partisans over the fascist invaders.

However, it is still important in that it was one of the very first lapidars to be installed in the country – and the first one that attempted to tell the story of the National Liberation War (the earlier statues were of Joseph Stalin).

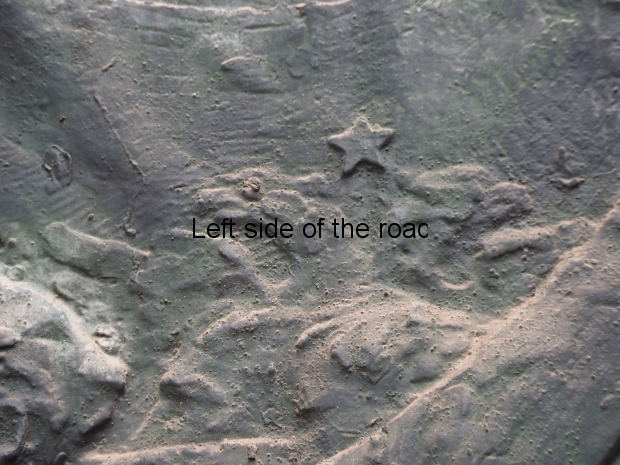

Bas reliefs

On either side of the statue, on the plinth, there are two bas reliefs. They are not in a particularly good condition and are showing the signs of wear but through time rather than any vandalism. Nonetheless they play an important role in the history of Albanian lapidars as they start to establish artistic ‘tropes’ which were emulated, with various adaptations, by later Albanian sculptors.

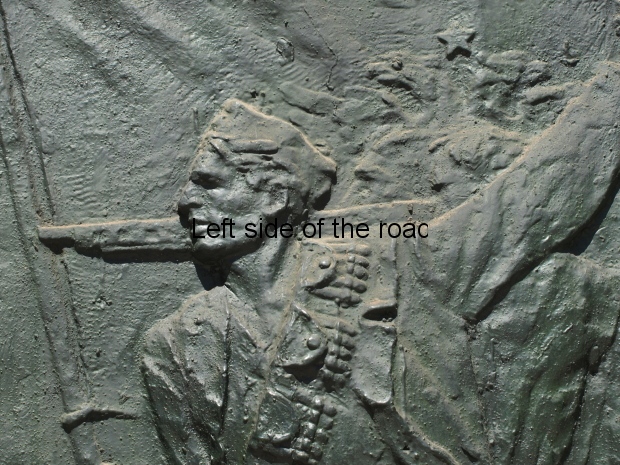

Monument to the Partisan – Bas relief 1

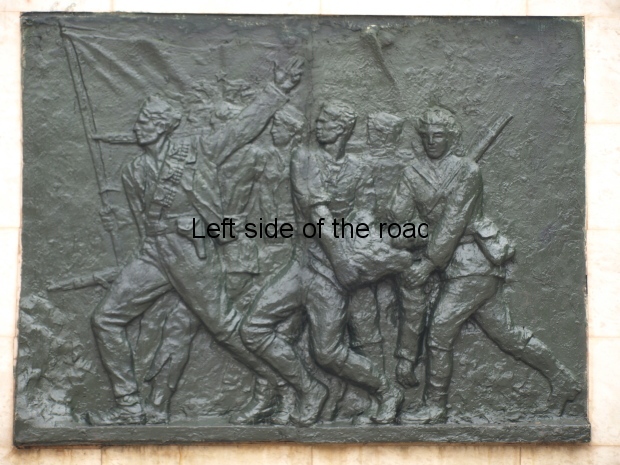

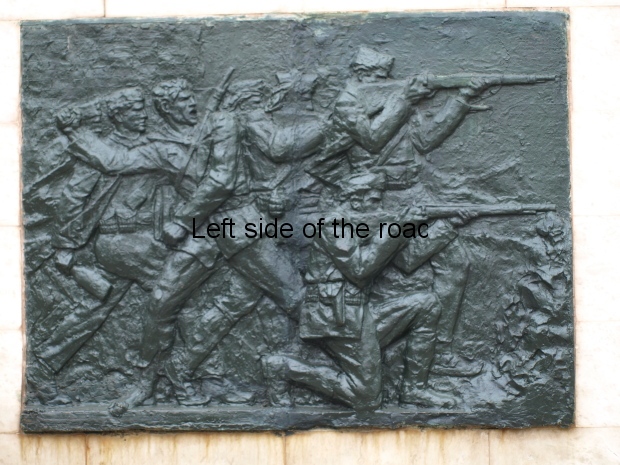

The one on the right of the monument as you look face on to the Partisan (i.e., on the left of the statue itself) depicts a small squad of Partisans – in this case seven – in the middle of a battle. However, the juxtaposition of the figures seem to represent more than one event.

The backdrop to the scene is the Communist flag. This is a red flag upon which, in the centre, is a black, double-headed eagle. This symbol was taken from the emblem used by Skenderbeu in the nationalist battle against the Ottoman’s in the 15th century. It was brought into the 20th century with the addition of a gold, five pointed star, which sits exactly in the central space between the two heads. This flag was later adopted as the national flag of Albania after the defeat of the fascists on 29th November 1944. (The present national flag has exactly the same arrangement but without the gold star.)

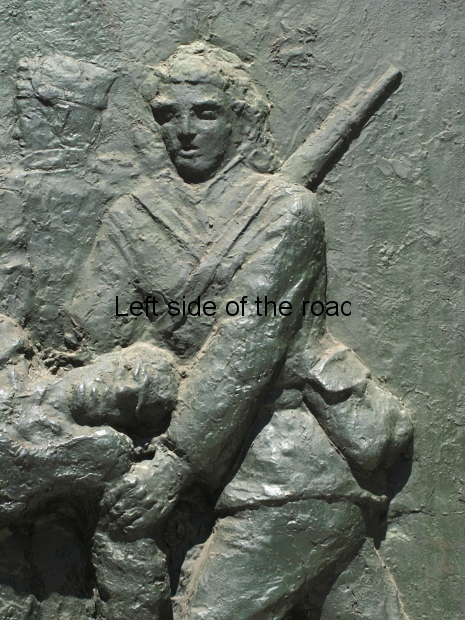

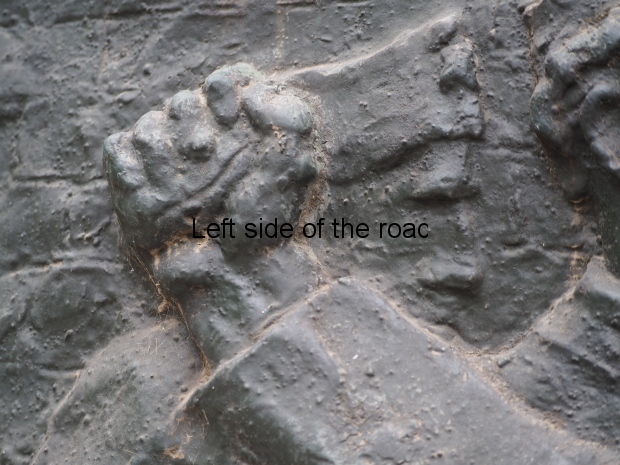

The principal figure in this panel is a full length, left profile of a Partisan officer. He’s in a full partisan uniform, military jacket and trousers, with the jacket unbuttoned and the left edge being pulled away from his body by the action of his raised left arm. As is usual we know he’s a Communist as there’s a star on his cap – but he doesn’t have a scarf around his neck.

Hanging from his left shoulder, and going across his chest, is an ammunition belt. We can see three clips with five bullets each which are for the rifle he holds in his right hand. We can’t see it but his right arm is fully extended downwards and he must be holding the rifle around the trigger mechanism as we only see the spurting end of the barrel and a small piece of the strap attached to the wooden stock.

The rifle could be a Delaunay-Belleville Model 1907-15 (there’s an example of it in the National Historical Museum (National Liberation War room) in Tirana). The company was a luxury car maker before the First World War but went into war production after 1914. The fact that the Partisans used, in the main, either such old weapons or those they took off the fascist invaders (first Italian and the German) gives an indication of the nature of the force that destroyed Nazism in Albania – using anything and everything to defeat the invaders.

On the belt around his waist there’s a pistol holster thus indicating his officer status (as mentioned above when talking about the statue). His left arm is raised fully above his head and his partially open hand is indicating for all those behind him to come forward for battle.

Finally for this figure we can see that although in full military uniform he is wearing opinga on his feet – the traditional Albanian shoe with a distinctive turned up nodule at the toe.

Above the left shoulder of this officer we can see two partial faces of two male Partisans. Neither is wearing a cap. The figure at the back is the standard bearer as we can see his right hand gripping the flag pole just beneath where the material is attached to the pole. The other figure has a gun raised closed to his face as if he is aiming. Part of the gun is seen running parallel to the top of the officer’s shoulder and the end of the barrel appears behind his face, at the level of his mouth.

This could be a Bereta, 1938, 9mm calibre, automatic rifle. Again there’s one of those in a glass case in the Tirana National History Museum, just in front of the impressive ‘Death to Fascism’ mural. This would more than likely have been taken off a dead Italian invader earlier in the campaign.

The Partisan with the automatic rifle seems to be wearing the traditional trousers called tirq, which don’t quite extend to the ankle and are split the last few inches. He also appears to be barefooted.

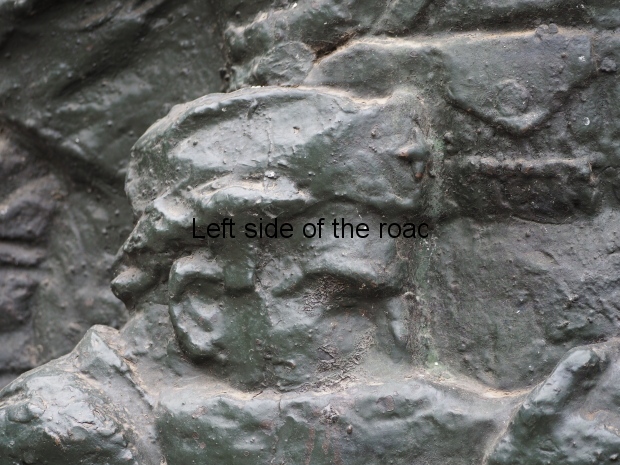

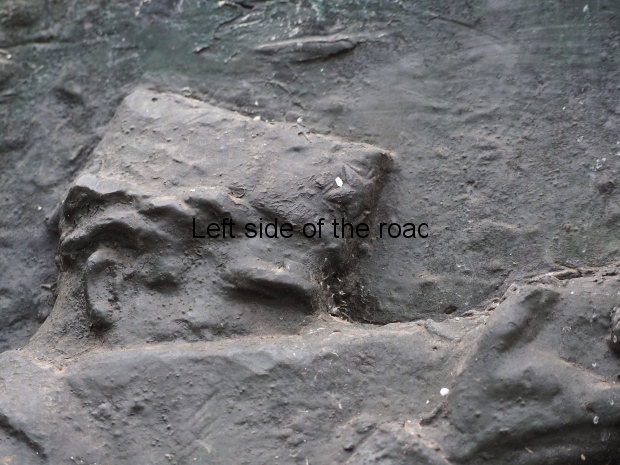

Behind of, and seen below the raised arm of, the officer is a female fighter – the first of two on this panel. Her face is in profile, she has long hair (tied up) and she appears to be wearing a cap and I think there’s a hint of a star on the front of the cap. (The problem here is that wear and tear makes some of the detail difficult to make out.) She’s dressed in military uniform but all we can see is an ammunition clip (the same sort as we saw on the officer’s belt) at her waist. We can’t see anything else of her as she’s hidden by the other figures but we have to assume that she too is armed.

The next part I don’t fully understand. This is, if you like, a tableau within a tableau and is reminiscent of the sculpture in Permët Martyrs’ Cemetery called ‘Shoket – Comrades’ by Odhise Paskali.

In the centre is a male figure who has obviously recently been seriously injured as he is slumped backwards although still (just) on his feet. He is depicted as if he were crumbling, without the strength to stand up by himself. Both his knees are bent and his body is so close to the ground his left hand almost touches the earth. The reason he is not on the ground is that another of his comrades has his hands linked so that he provides a supportive loop around the body of his wounded comrade’s waist. The other reason the wounded Partisan is not on the ground is that a female fighter has her left hand gripping his left arm, high up by the armpit and we have to assume her other hand, unseen, is supporting him on his right side.

There is no evidence of any weapons for the two males and it’s difficult to make out exactly how they are dressed. They appear to be in uniform but the male really struggling to keep his comrade from falling down has the sleeves of his shirt rolled up to the elbow. Again strangely, for me, he is also looking forward, in the direction of the advance rather than looking down at his comrade.

There’s also a difference in what they are wearing on their feet. The wounded man is wearing the opinga whilst the ‘healthy’ fighter has the more recognisable military boot.

The female Partisan is the only one we see in full face. In supporting the fallen soldier she has turned so that she is the only one not looking in the direction of the battle, whether taking place or about to start – although the injured Partisan indicates that bullets have already started to fly. She is also in full uniform, seems to be wearing boots but not a cap to cover her long hair. There are two straps coming from both her shoulders across her chest, one of which supports a bulging satchel resting on her left hip the other on the end of which is a huge rifle (almost like a cannon) the end of the barrel of which points to the edge of the panel.

What I don’t understand here is why are they supporting him in the middle of an attack. The bulging satchel indicates she might be a medic but the big rifle indicates she’s definitely a fighter and not a non-combatant. Are they, perhaps, taking the wounded man away from the action but if so, again, why? Yes you want to look after your fallen and injured comrades but if the two carrying the wounded man are also combatants then three, and not just one, fighter is being taken out of the fight at a crucial time. Perhaps he represents the last to die in the liberation of Tirana and only days away from the liberation of the whole country. Whatever the idea it’s a bit of a mystery to me – and something I’ve not come across elsewhere, as far as I can remember.

Finally we have more of a silhouette than a bas-relief. Between these last male and the female, and just above the body of the falling man, is the shape of another male Partisan. Again the figure is in left profile and appears to be in uniform, including a cap. But further than that it’s difficult to say.

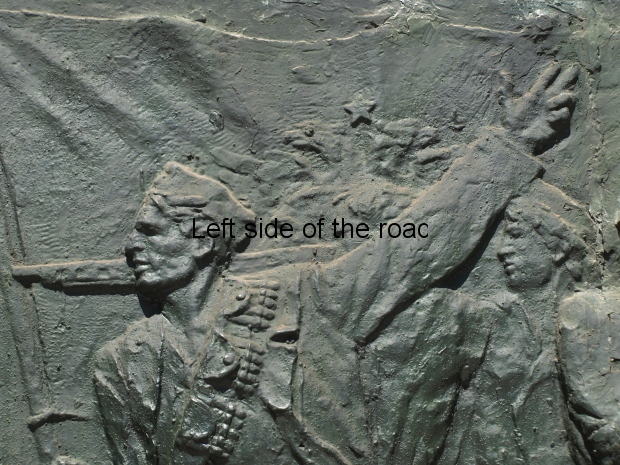

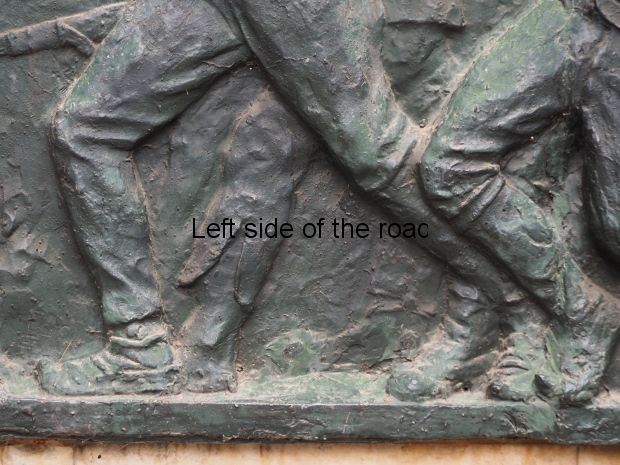

Monument to the Partisan – Bas relief 2

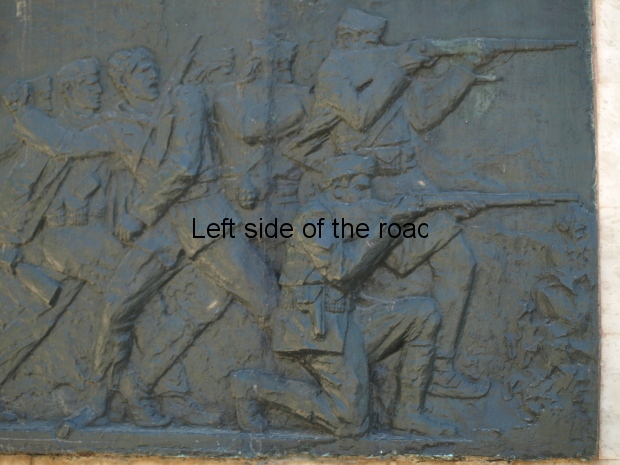

If the story in the first bas relief is, at times, difficult to follow the second one is much more basic and straightforward. Here we also have seven partisans (this time all male) in a full on attack. Here no one is holding back and it’s full of action.

All seem to be in full Partisan uniform. Half of them have caps, with signs of the red star, but half do not.

Mallakaster Partisans – possibly 1943

(Here it might be worthwhile to say that before the beginning of the organised Partisan onslaught against the Italian invaders, following the Peze Conference of 16th September 1942, the Albanian forces were more of a guerrilla force. Their tactics were very much that of hit and run – and they were very successful at that even before the Conference. However, the Conference gave structure to the struggle and as part of that uniforms started to become more common. Whether that brings with it certain negatives is a debate for another time but what it did lead to was a more organised opposition and by the time of the liberation of Tirana, on 17th November 1944, most of the troops that entered the city would have been in uniform.)

At the front we have two Partisans, one kneeling one standing, both with their rifles on their shoulders and they are firing whilst looking through the sights. Those two are heavily armed, both have extra ammunition on their belts and the one who is kneeling has a pistol holster on his right hip.

Behind them, also standing and firing with his rifle at his shoulder, is another Partisan. Again heavily armed but this time with a grenade attached to his belt. This is, in fact, a Mills bomb, a British made grenade. This is the grenade that looks like a very small (yet lethal) pineapple. The end of the barrel of his rifle pokes out behind the standing marksman in the front rank.

As the British weren’t fighting the Nazis in mainland Europe until June 1944 – whilst the Albanian Communists had been fighting them for almost two years – the Partisans were more than happy to take any weapons that came their way. Consignments of Mills bombs were part of that ‘support’. The problem was that the British thought that by providing such assistance they had the right to determine what sort of society should be developed in Albania after the end of hostilities. The Albanians didn’t agree and had to endure decades of attempts by the British imperialists to subvert Albanian Socialism.

We only see part of the head of the next fighter so we can only speculate what he is doing, but probably the same as the first three.

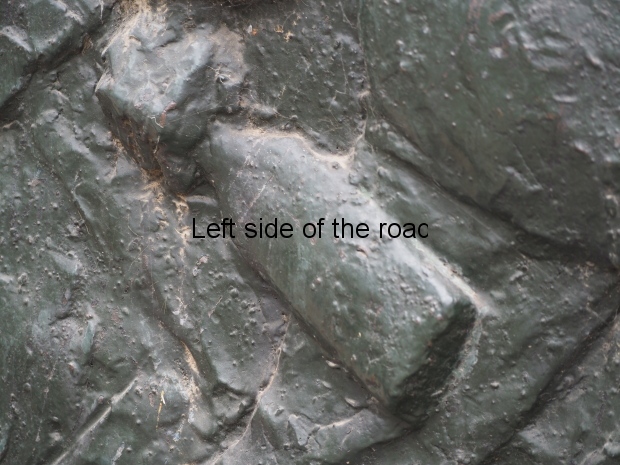

The next figure is the most dynamic of the lot. The strap across his chest is for his rifle and the top of the barrel can be seen over his left shoulder. He is leaning back and his right arm is slightly bent but extended behind him. In his hand he holds a Mills bomb and his stance is one that will give his body the greatest chance of throwing the grenade with the greatest force to where he wants it to land. To make sure he is steady he has his legs wide apart giving extra stability as well as more force for his throw. As on the other panel there is a variation in the clothing and this ‘grenadier’ is wearing traditional tirq trousers (short of the ankle and split at the bottoms) as well as wearing the opinga. He is also the only one with his mouth open – announcing to the Nazis what they could expect from his British present.

Although he doesn’t wear a cap he has a scarf around his neck indicating, yet again, that he is a Communist. Always, on Albanian lapidars, the star and scarf, both of which would have been red, indicate a Communist. Although not all Partisans were Communists they were the majority in the National Liberation Front.

The next figure is also rushing forward, indicated be the bottom edge of his jacket being thrown back in his haste. This allows us to see that he, too, has extra rifle ammunition clips (two) on his belt. But he’s not seen with a rifle but with another grenade.

However, this is not one ‘kindly donated’ by the British, this one is a present he is returning to the original owners as this is a German made stick grenade. He isn’t ready to throw yet so he just grips it tightly in his right hand, his arm extended downwards. The advantage the stick grenade had over the British version (unless the thrower was good at cricket) was that the long stick provided a lever motion and so increased the distance thrown. However, its size went against it as less could be carried. But here we are shown that the Partisans used weapons from all sources, none being rejected.

Finally, and barely discernible, behind the two grenadiers is part of the head of another male Partisan. The star can be made out on his cap but there’s little else that can be said about him.

Establishing the artistic ‘tropes’

The ‘Monument to the Partisan’ was, as I’ve already said, the very first true sculptural lapidar. The sculptor, Andrea Mano, also spent a great deal of his working life teaching his art – first in a High School and then at the finest Art School in the country, the University of Arts in Tirana (from 1954-1982) – and therefore coming into contact with the young and upcoming, post-Liberation trained sculptors. So there’s no real surprise that some of the images he used in his early work re-appeared in an often more sophisticated manner.

Those artistic ‘tropes’ I think can be seen in this monument are;

the raised arm, often with the individual looking in the opposite direction to where the action was taking place, signalling for those unseen in the work of art to come and join the fight, battle or general struggle. This can be seen in the Arch of Drashovicë,

armed women, of all ages. If the lapidar (be it a sculpture, bas relief or mosaic) is telling a story of armed conflict then the women (if not all the men) will be armed. This references the fact that if women want true liberation they will have to be prepared to take arms to achieve and/or retain those gains. This can be seen in ‘The Albanians’ mosaic on the facade of the National Historical Museum in Tirana, the Martyrs’ Cemetery in Lushnjë and the statue of Liri Gero, in the ‘Sculpture Park’ behind the National Art Gallery in Tirana.

the footwear telling a story. The traditional opinga mixing with the European boot (indicating the changing culture as well as a connection with the past), or even sometimes individuals will be barefooted, referencing the extreme poverty of a huge part of the population, yet still prepared to fight for freedom and liberation from oppression.

images of traditional clothing. This is similar to the issue with the footwear but from a slightly different angel. Clothing would indicate from which part of the country an individual might call home. This was in an effort to indicate to the viewer that the revolution, and the war against the invader, was something that involved all of the country, with its different ethnic groups. This also helped to show that the struggles involved men and women of all ages, with the older perhaps still hanging on to the traditional when it came to dress but prepared to fight together with the young with more modern ideas of fashion.

its quite interesting to see how often the clothing being shown as if it has been caught in the wind so as to give the impression of speed, especially when rushing to a battle. This was often seen in conjunction with ‘the hand calling to action’ motif.

Although I wouldn’t go as far as to say that visiting the ‘Monument to the Partisan’ will mean you have seen all that the lapidars have to offer but it would be a good place to start to compare with any you might encounter in other parts of the country.

Inscription

Plaque on the Monument to the Partisan

If you look at the picture at the very top of this post you will notice the inscription (although the same wording) is different from what is in place today. I have no information about when the old, stand alone metal letters and numbers might have been removed. It might have been political vandalism at some time in the 1990s or it might have been simple theft – all societies will always have scumbags who will steal the smallest items for a minor profit – in the past, the present and the foreseeable future.

Whatever the fate of the inscription what is noticeable is that the star did not reappear on the replacement marble plaque. I have seen it in other locations, where a carved star will be at the top of the new plaque but not here. (I’ll have to write a post one day bringing together the fate of the ‘Communist Star’ in Albanian lapidars.) Here it might be enough to just say that for the reactionaries in Albania the Red Star is second only in the hate league table to Enver Hoxha. But as Chairman Mao said ‘To be attacked by the enemy is not a bad thing but a good thing’.

The wording on the front of the monument, originally and at present is

in Albanian;

Populli i Tiranës partizanëve të rënë për çlirimin e kryeqytetit 28/X–17/XI/1944

which translates as;

The People of Tirana to the Partisans who fell during the Liberation of the capital, 28th October to 17th November 1944

Sculptor

Andrea Mano (1919-2000) was a pre-liberation sculptor, in the sense that he was born in 1919 and followed his education in Italy – before the Italians decided to invade Albania on 7th April 1939 as part of the Fascist plan to take control of Europe. That would seem to indicate he came from a relatively privileged background. He returned to Albania in 1942. I have no information whether he took an active part in the National Liberation War – or not. He couldn’t have been all that bad as, in 1946, he was given a scholarship to study in Zagreb, Yugoslavia – before Tito decided that he could take the country on a road to ‘Socialism’ different from that of the one indicated by Marxism-Leninism. This meant Mano had to return to Albania in 1948 and that must have been when he was awarded the commission for the Partisan Monument.

He was involved (together with Odhise Paskali and Janaq Paço) in the major sculpture of the equestrian Skanderbeu, which was installed in the central square in Tirana which bears his name in 1968 – the 500th anniversary of his death. In the process ousting the Soviet made statue of Joseph Stalin to a little bit down the road.

He was also one of the sculptors responsible for ‘The Four Heroines of Mirdita’ (1970) – together with Fuat Dushku, Perikli Çuli and Dhimo Gogollari. Tragically this amazing structure was one of the first victims of the reaction and was destroyed in 1993.

Four Heroines of Mirdita, Rreshen

Although he produced smaller works that have been displayed in the National Art Gallery in Tirana he seems to have devoted most of his time to the teaching of his craft.

Location

Sheshi Sulejman Pasha

Tirana

This square is behind the building that houses the Opera House and the National Library and also where the buses leave to go to the airport and those that will take you to the cable car of Dajti.

(This is just beside Rruga George W Bush – which makes me almost want to vomit to type the words. There’s even a statue to ‘GW’ in Fushe Krujë, can you believe it?)

GPS

41.32813901

19.82198697

DMS

41° 19′ 41.3004” N

19° 49′ 19.1531” E

Altitude

113.1m