More on Argentina

Football and the ‘incidente’ of Saturday 24th November 2018

Although I knew that football was big in Argentina (with a fervour that makes European teams’ supporters appear like casual watchers) I didn’t think that I would be writing about the topic within 36 hours of arriving in the country.

The background, as even non-football supporters will probably know about by now due to what happened yesterday, is that two Buenos Aires based teams, River Plate and Boca Juniors, were due to play the second leg of the Copa Libertadores Final in the home stadium, El Monumental, of the River Plate team. With such an intense rivalry between the two teams it had been agreed, a long time in advance, that away supporters would be banned from the game.

I knew nothing of this and the first time I was aware of any match being played at all, not taking into account a major cup final, was when I was walking in the central area of the city and saw (and heard) Boca supporters driving around the streets in buses, cars and on motorbikes, tooting on horns and waving flags and shouting the name of La Boca before heading to some bar to watch the match on TV.

The little bar I went to, situated in the same building complex as the Ministry of the Interior, had the TV on, and was expecting people in later to watch the match. I decided that if matters got too intense I’d move out. However, although it took some time for me to realise it, what was drawing the attention of the bar’s clients wasn’t the match itself but the ‘incidente’ that had occurred as the Boca Juniors team bus arrived at the El Monumental stadium and how that panned out over the course of the next few hours or so (and unbeknownst to all of us at the time, for an indefinite time in the future).

The following ‘report’ will be from the view of the locals (or at least my interpretation of that view) who saw matters, I think, slightly different from the way it might have been presented to Europeans by the likes of the sanitised version I read from the BBC on the Sunday morning.

The ‘facts’ are that the bus, bringing the Boca Juniors team and officials (only from the other side of town) was attacked by the River Plate ‘hinchas’ (obsessed fans) and stones and bottles thrown and that the Prefectura (the national naval police) decided to spray the River Plate fans with tear gas. But as with all ‘facts’ that statement might be open to interpretation.

Now, as we all know, especially in Europe as the anniversary of the end of the 1914-1919 World War has just been ‘celebrated’, that the use of any gas against people is a very tricky and fraught exercise. You can’t control who it effects, sometimes the target, sometimes yourself and sometimes the ‘innocent’. And in this case the ‘innocent’ were the Boca Juniors players and officials.

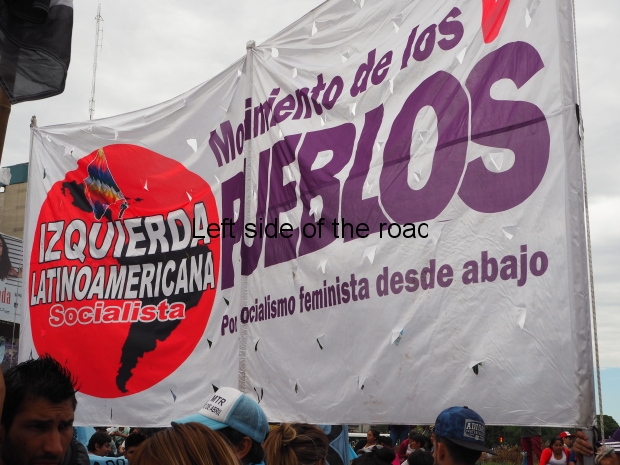

Now I’m not going to comment on the rivalry between different football teams’ fans. Sociologists worldwide, I’m sure, have tried to understand how such rivalry often leads to extreme situations. The various states and the worldwide media have a lot to do with it. Keep people fighting amongst themselves over who wins a game of kicking a ball around for an hour and a half and they might not fight back against capitalism (which also makes a fortune out of the fans support in ticket sales, merchandising and TV rights) and the shit conditions into which it forces huge sections of the population, in many countries and on a regular, cyclical basis. This is the modern day equivalent of the ‘bread and games’ tactics of the Roman Emperors. However, present day capitalism is more ‘developed’ in keeping its populations docile and less of a threat to its existence. They make the population pay through the nose for the distractions which make them forget their miserable existence.

When it comes to the ‘incidente’ of 24th November 2018 there are other questions that need to be asked yet almost certainly won’t be answered. The state creates the situation where there’s a likelihood of an explosion but then walks away and blames the people it has created.

What was interesting for me, in a tiny out of the way bar, which, I thought at the time was filled with Boca Junior supporters (bars in Hispanic countries, from my experience, are openly and clearly partisan when it comes to football but I learnt the situation in Argentina seems to be more relaxed) was that what the customers were saying was not against the supporters of River Plate who were throwing stones and bottles but was more against the police and the organisers in general who were displaying a total lack of organisation to allow such a situation to arise in the first place.

So to the questions being asked:

Why was the bus taken on a route and at a time when it was obvious it would have to pass River Plate ‘hinchas’, many of whom wouldn’t have been able to get a ticket?

Why, when there was a situation where tensions would get high, was there not a more obvious police presence so that matters could have been kept under control before getting totally out of hand. (Here I must state that I’m not a lover of any state’s police forces but even under capitalist rules they are there to do a job. When they fall down on that job they should be held to account.)

Why did they send a bus which could have its windows broken, even those on the top deck, by someone just throwing a stone from street level? I thought windscreens and modern day vehicle windows were of toughened, shatter-proof glass yet the windows seemed to have been broken easily. (I’ve seen films where even an angry giant armed with a sledge hammer has barely made a dent in the glass.)

Added to that the bus was moving quite fast at the time. If the persons (as there must have been at least 4 or 5 broken windows on both levels of the double decker bus) who threw the stones that were so effective in breaking the windows of the bus are ever found they should be trained in some sort of throwing sport as they must have produced Olympic world record breaking examples of strength to have achieved what they did.

Why did officers of the Prefectura, the Naval police (if I understand it correctly) just fire a random burst of tear gas from a moving van at the River Plate supporters in the vicinity of the attack? They seemed to have disappeared from the scene as I wasn’t aware of them appearing on the TV screen in the couple of hours I was following the unfolding of the events. In fact the first, and only time, I have seen this burst of tear gas come from a speeding vehicle was when I had the opportunity to see the video posted on the BBC website on the Sunday morning. And this is after watching the same scenes from the attack and its consequences being repeated ad nauseum on the couple of channels that were flicked through in the bar. Surely, this might be something that conspiracy theorists should be looking into?

It was the effects of this gas that was being highlighted in the early reports from the Boca Juniors dressing room in the El Monumental stadium. Pictures of the team and the officials arriving had them looking dizzy and some of them trying not to vomit – classic effects of a tear gas attack. It wasn’t till much later that reports of actual physical injury caused by flying glass started to appear on the screen. At the same time the importance of the tear gas and the effects it was having on the players was what has been played down in the reports I’ve seen on the BBC English news website.

As the afternoon drew on it was obvious that images were being sent into the news stations by members of the public who were at the scene of the attack and the confrontation between ‘los hinchas’ and the police.

For a short time there was the definite chance that a major confrontation was about to develop between the River Plate fans and the police. A small contingent of police in riot gear were the target of stone throwers and they seemed to be more interested in protecting themselves than confronting the opposition And this made sense, at least at the beginning.

The live images on the TV were taken from a high vantage point and here it was clear that there couldn’t have been more than about 30 or so police all geared up in their protective clothing. However, as the afternoon wore on images started to come through from either videos produced on Smartphones or from film crews sent in to cover the action. There the same story, told from the side of the stone throwers told a very different story.

The early images showed police doing the minimum, the later images seemed to present them in a much more threatening and aggressive manner. Who said the ‘camera never lies’? When we all should know that the camera never tells the truth.

And whilst these images were being shown on the screen it was the authorities who were being criticised by the people in the bar. Too few police, no preparation for such a major and emotional event, inadequate response to a situation that could go in any direction. If the situation didn’t get totally out of hand then it was due, to my mind, to the fact that the River Plate fans didn’t want it to. Pictures showed some of them passing through police lines and out of the ‘front line’.

One image, that appeared for only a short time was of a crew of 4 or 5 police officers, this time not in full riot gear, get out of a vehicle and point what looked like tear gas guns at the crowd. I don’t think any were fired and the police were only out of their vehicle for a short time so don’t know if someone told them to clear out. Firing more tear gas would have almost certainly have escalated the situation.

Now a look at the response from the football authorities themselves. If the police and government authorities didn’t have a clue what they were doing those in charge of Argentinian and world football were even more in disarray.

Their aim, as it soon became evident, was that the show must go on – at any cost. Not to the players, not to the spectators in the stadium, not to the those watching at home (whether that be in Buenos Aires or anywhere else in the world). No the show must go on because of TV rights – which we all know is what is most important in world football today.

This didn’t appear on the screen that I could see, amongst a number of quotes from those officials that were flashed up from time to time. However, this crucial matter was mentioned in a quote from the BBC report of the following morning where the Boca Juniors President is quoted as saying that making a decision on what to do was effected by ‘the television rights have been sold to a ton of countries.’

With that as their priority there was a refusal on the part of the football ‘authorities’ to accept that in no way was the game going to take place. Instead of looking at a way to force play (when it became increasingly obvious that there were injuries, if only temporary, to a number of the Boca players and that they wouldn’t have realistically been ‘match fit’, when statements were coming out from both the teams that they didn’t want to play, and even a casual observer such as myself could see it wouldn’t work on a whole lot of levels) those in charge of football should have been looking at how to get 60,000 people out of the stadium with the least danger to all concerned.

Reports that appeared the next day from those inside the stadium indicate that there was no sharing of information with that crowd of 60,000 people. That’s bad enough when they had been there in the hot sun (the temperatures in Buenos Aires that afternoon were in the mid 20s Celsius) for hours but in the age of social media what wasn’t been told directly to those fans was being drip fed to them from friends and family on the outside. It’s a good job there were no Boca fans in the stadium as in such a situation the whole affair would have turned into a massacre. (When I was looking at the TV screen I wondered why the pictures of the crowd only showed the red and white of the River Plate fans (as opposed to the blue and yellow of Boca) – that was whewn I didn’t know about the ban on away fans. Isn’t that a disgraceful comment in its own right on the state of world football?

I can’t imagine the situation in the stadium itself. The fans there stadium were effectively locked in. Those fans who had arrived after the ‘incidente’ with tickets were effectively locked out. And everyone was being kept in the dark as the question of the least expensive solution (to the football authorities and fat cats who cream millions off the ordinary fans) was being considered.

What started out as a gross miscalculation was starting to turn into a potential disaster. The fact that it didn’t was more due to luck than design.

Using my vox poular approach the whole process indicated that Argentina was ‘a shit country’, if such a situation had developed at the Casa Rosada ‘it wouldn’t have happened and ‘it’s impossible’. (I’ll come back to this approach to the Casa Rosada later on as on the only occasion I’ve been there I saw anti-demonstrator barriers which are on permanent standby.)

And to show how the relationship between the governing body had broken down the Boca management refused entry of Conmebol to their dressing room, reported on the TV screen at 18.20.

For the next few hours nothing was definitively agreed.

So we arrive at Sunday morning.

Basically nothing had been learnt from the events of the Saturday as sometime in the late morning it was decided that the match would go ahead at 17.00 on Sunday the 25th. Doubts began to be expressed on the TV, almost immediately, that this was still pushing it and with representations from the Boca Juniors club, who were producing a report to present to Conmebol, with them claiming they would have been at a disadvantage if the game was to be played so soon after the tear gassing and, we have to accept, not a little bit of shock when some of the team must have thought they were going to die, the game was again cancelled – this time with no alternative date being suggested.

As of now (the evening of Sunday 25th November 2018) there will be a meeting of Conmebol on Tuesday 27th November 2018 in Asunción, Uruguay. I don’t know if it was just a joke but one of the headlines stated that the second part of the final would take place in Abu Dhubai.

What also appeared on the TV screen on the Sunday afternoon were images of small confrontations between riot police and River Plate supporters. As is always the case in such situations the low deployment of police when it could have possibly prevented the ‘incidente’ is followed by an overwhelming police presence, under the pretext that this is to prevent matters getting out of hand.

But what is not being taken into account is the fact that there are a lot of fans, on both sides, who are pissed off with what happened yesterday, it’s a Sunday and so even those ‘lucky’ enough to have jobs may not be working, it’s still hot out there (mid to high 20s Celcius – the same as yesterday), the beer is flowing so it would only take a small spark to set things off.

If that happens I will write again about football. If it doesn’t then I will never write about football again in my life.

To sign off, do people remember the war that was ’caused’ by a football match? This was what came to be known as The Football War (La guerra del fútbol) and which lasted a 100 hours. This brief war was fought between El Salvador and Honduras in 1969. Existing tensions between the two countries coincided with rioting during a 1970 FIFA World Cup qualifier and things got out of hand.

So Shankley might have been right when he said that football is more important than life or death.

As a ps (which addressers the idea of who controls football and the whole idea of sponsorship) both teams have their shirts (the body) sponsored by the Spanish Bank BBVA.

More on Argentina

Previous Next