Ukraine – what you’re not told

The ‘Archive’ Exhibition at the Tirana Art Gallery

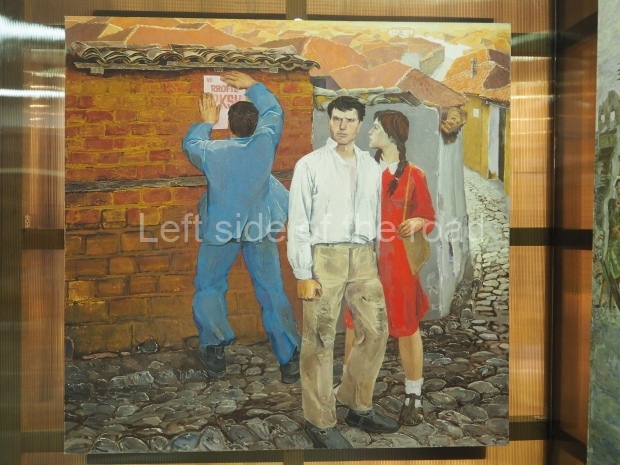

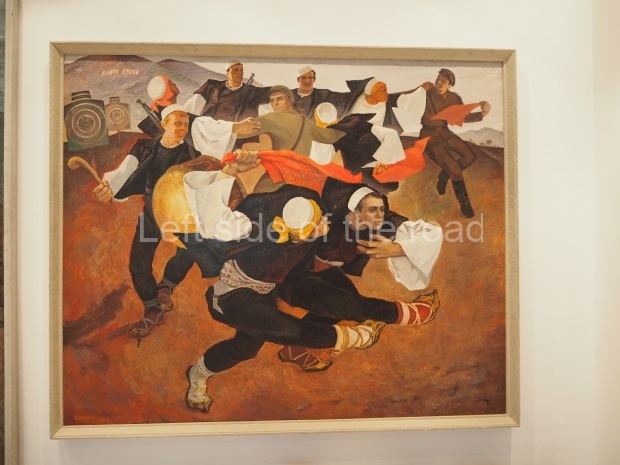

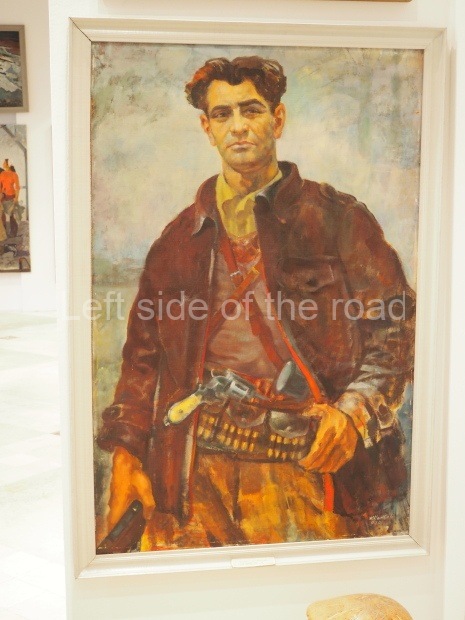

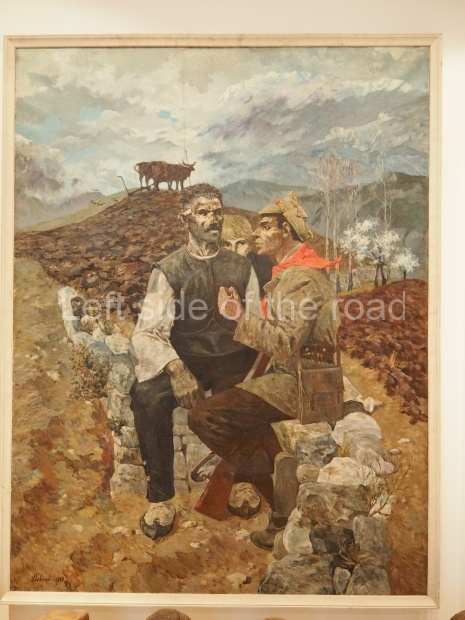

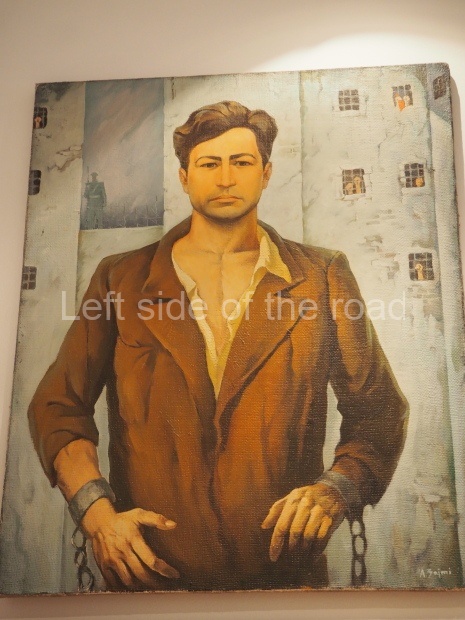

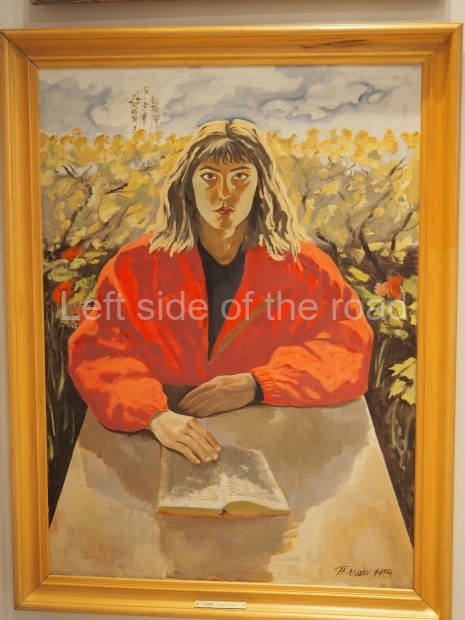

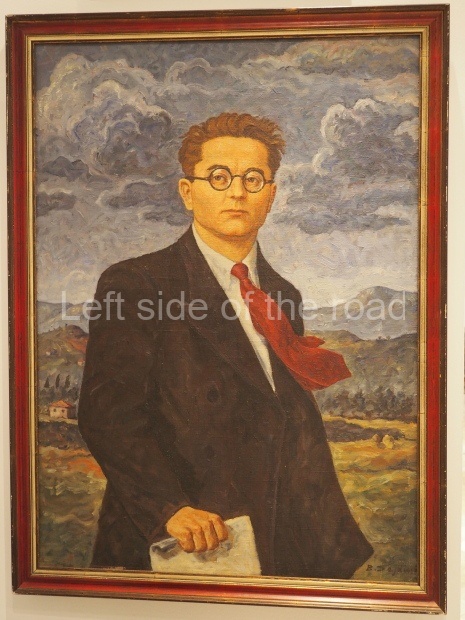

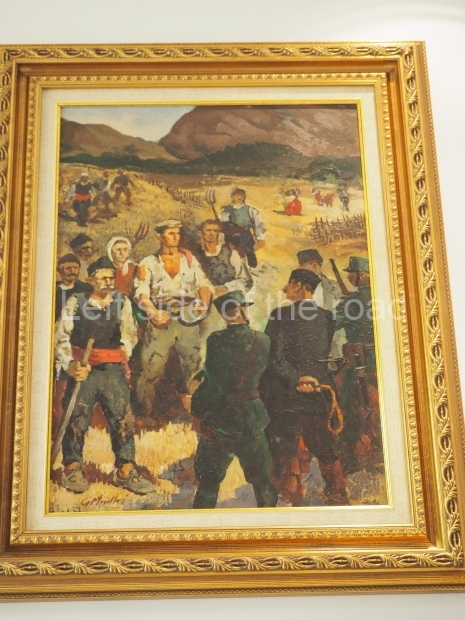

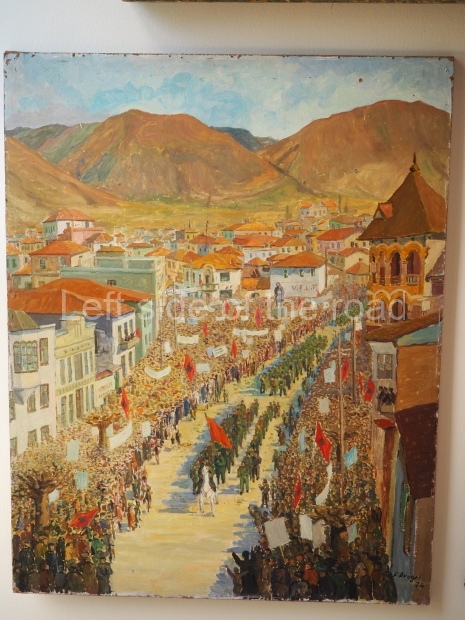

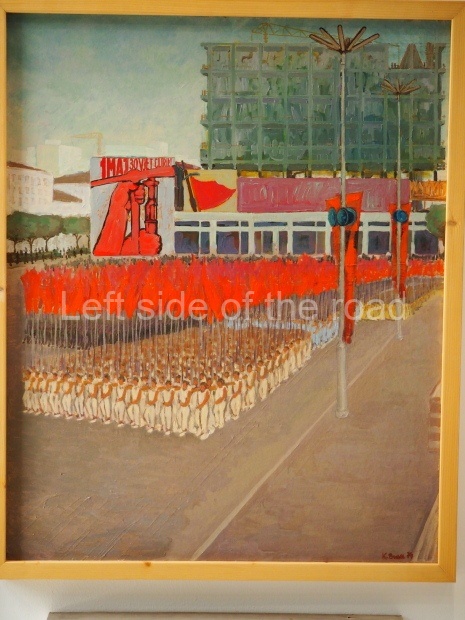

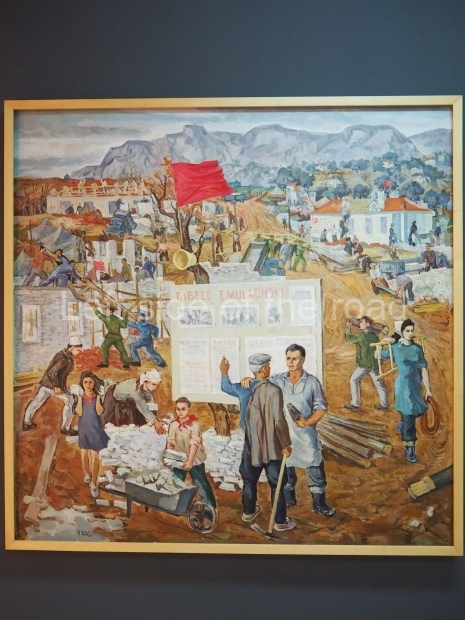

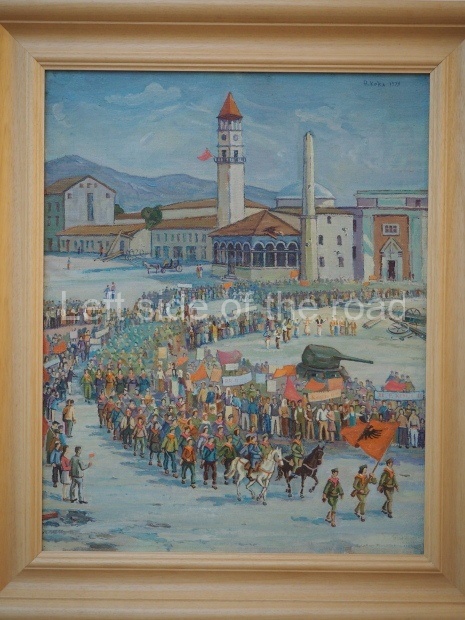

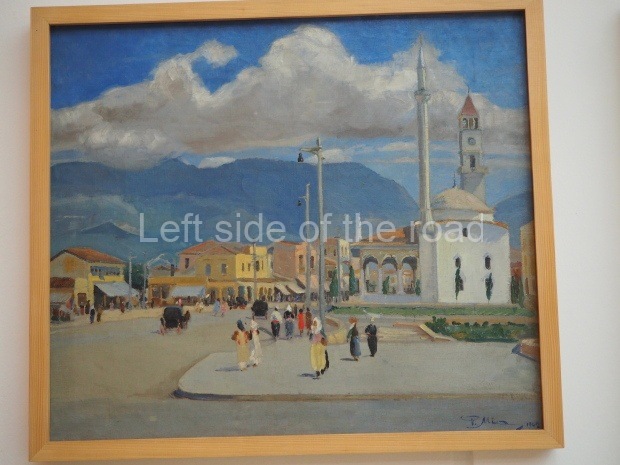

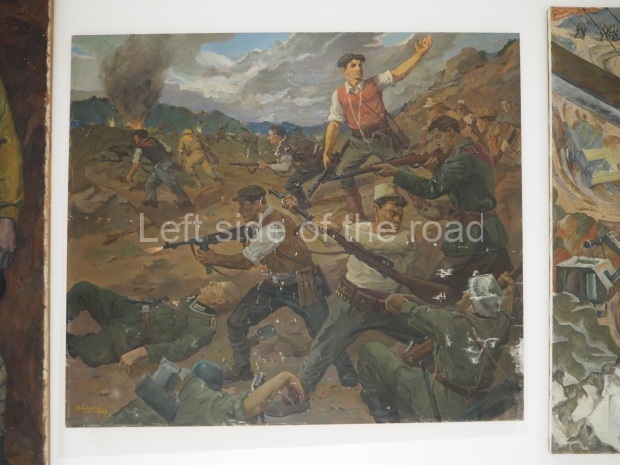

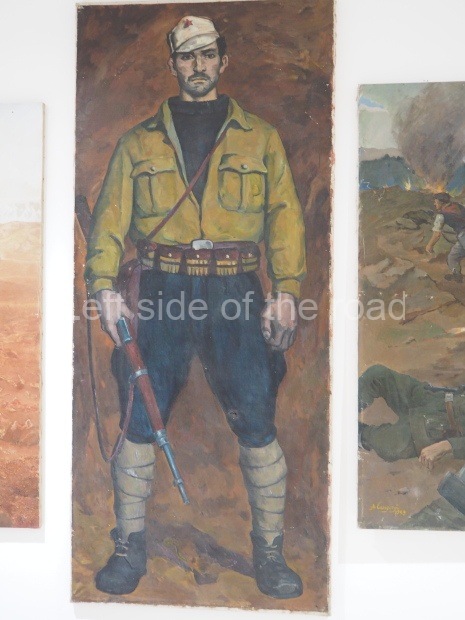

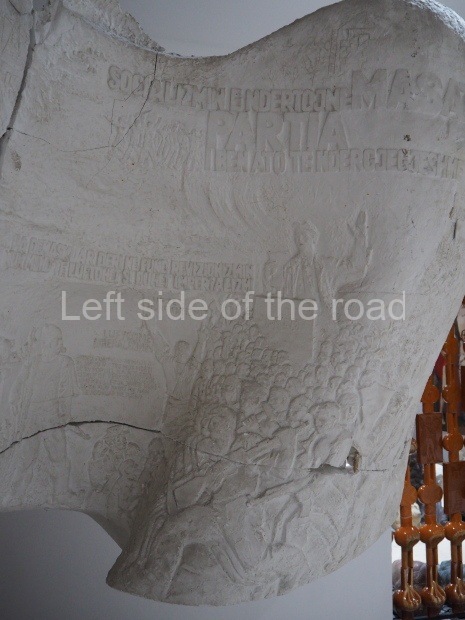

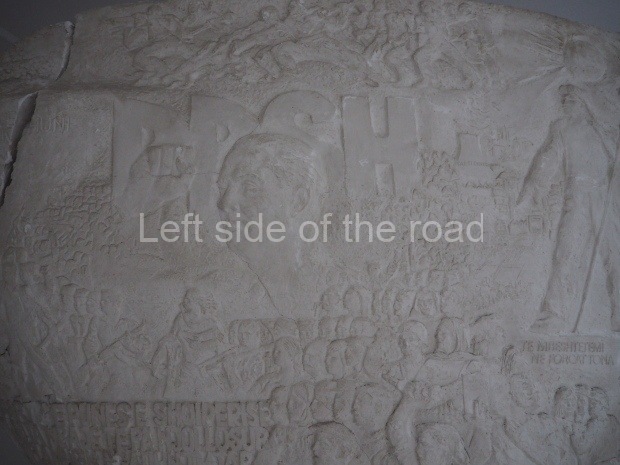

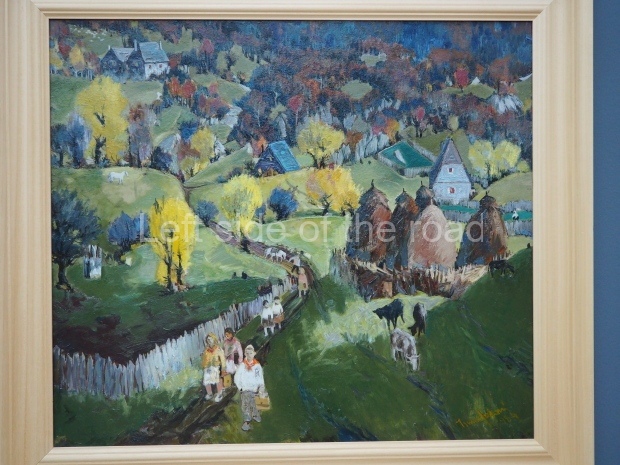

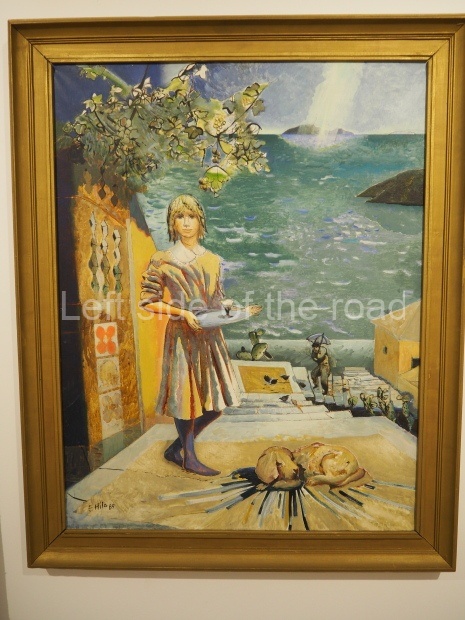

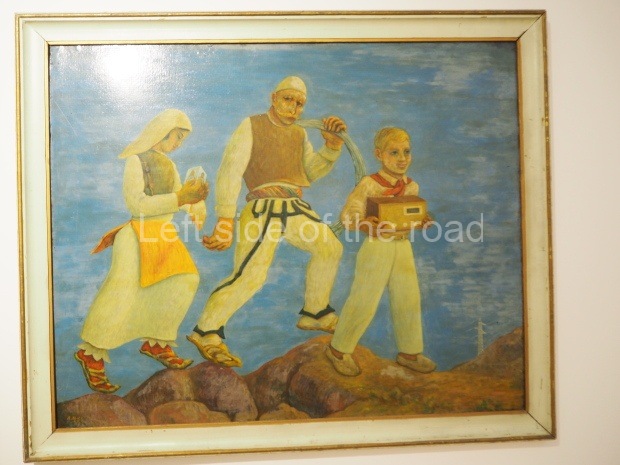

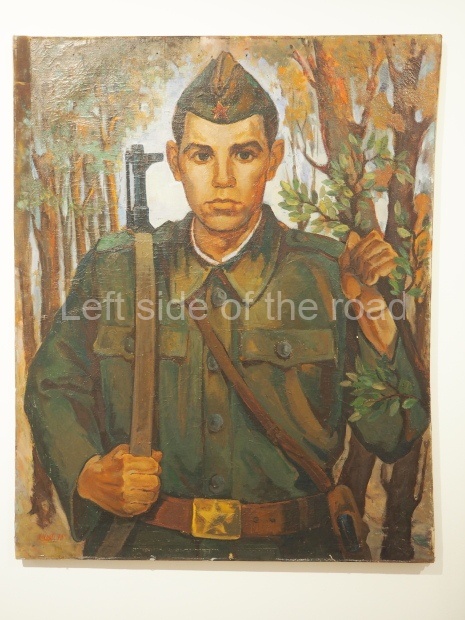

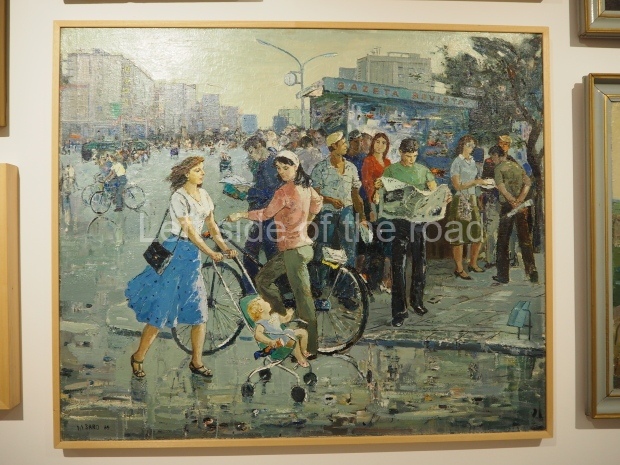

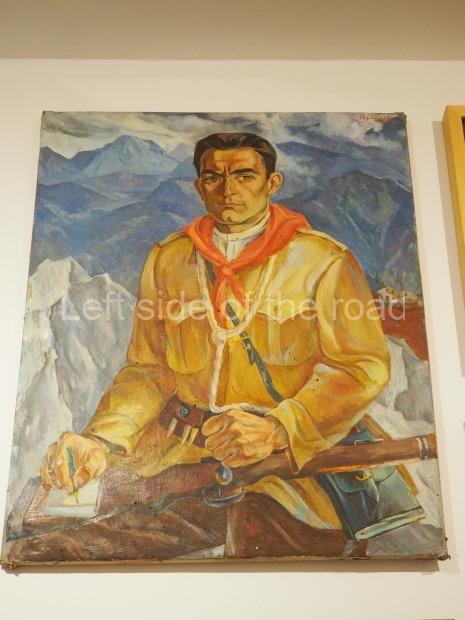

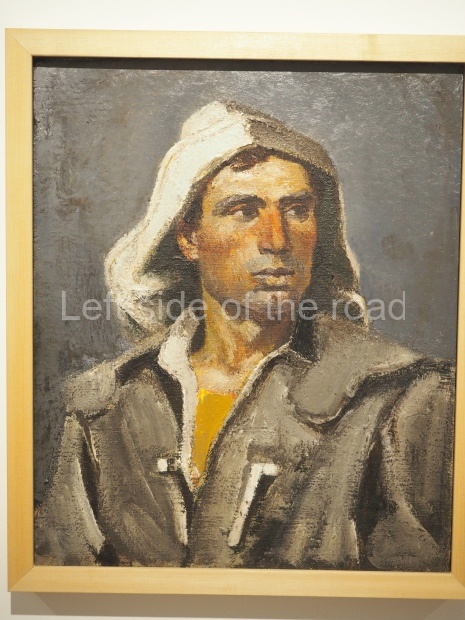

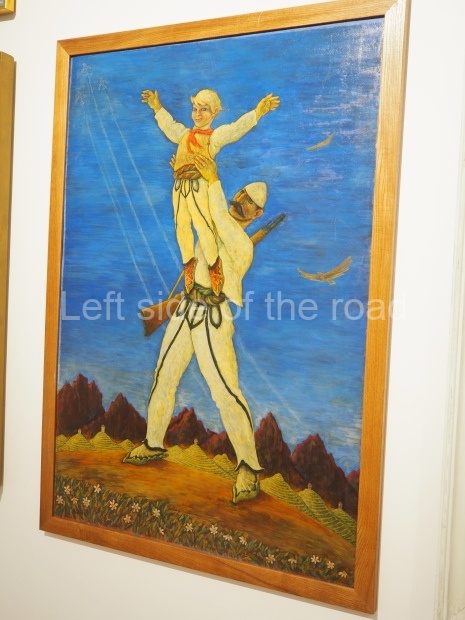

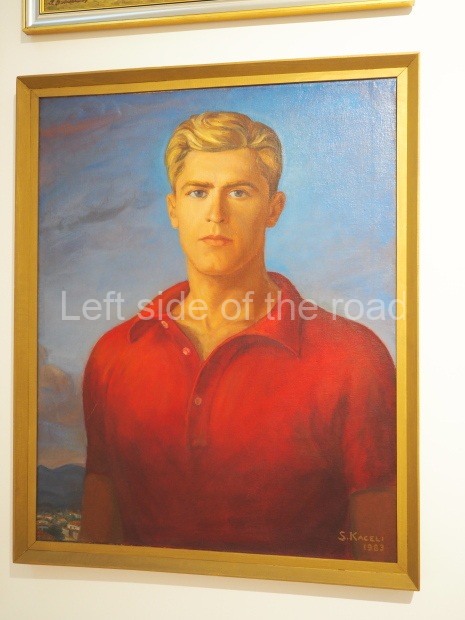

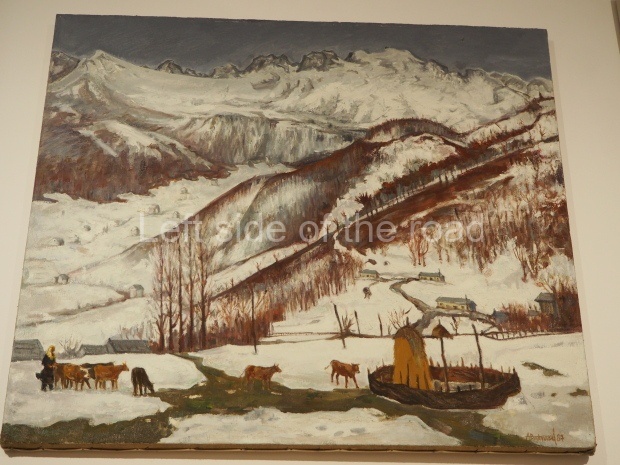

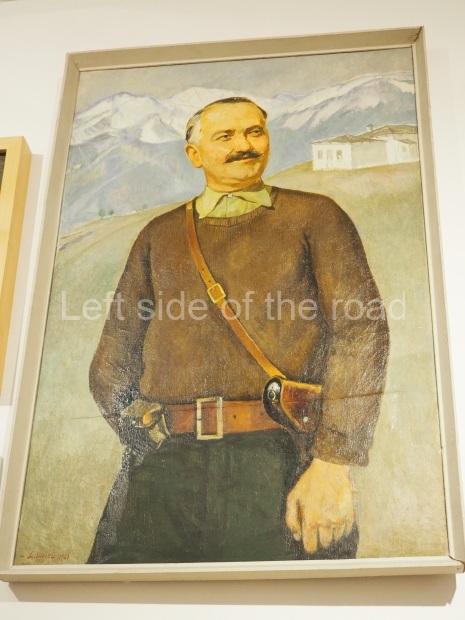

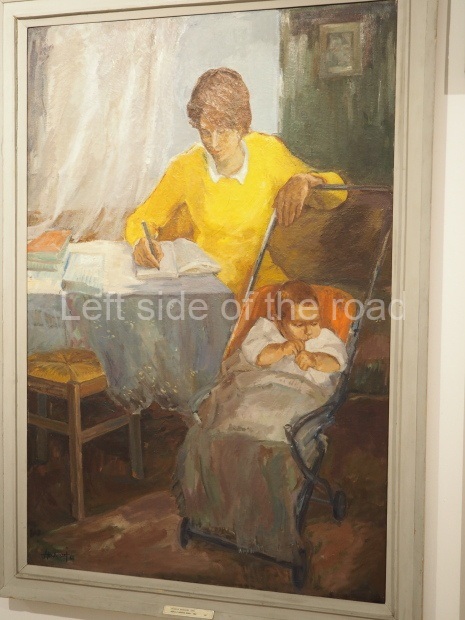

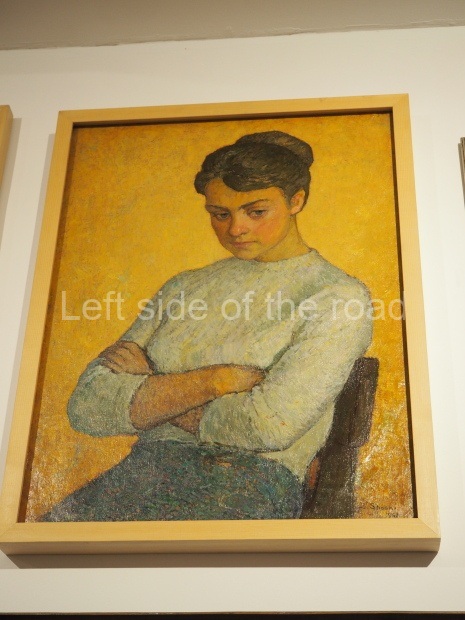

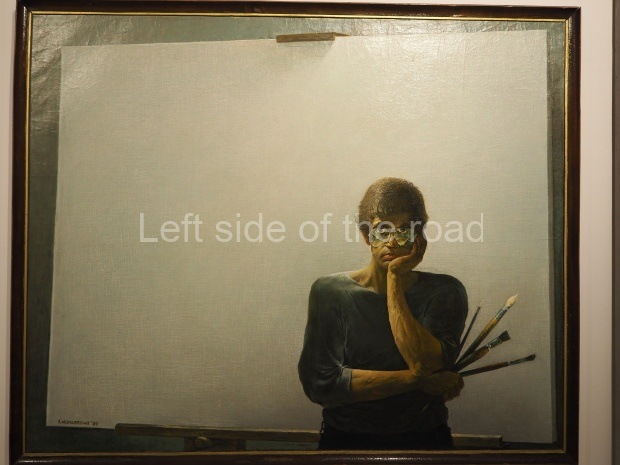

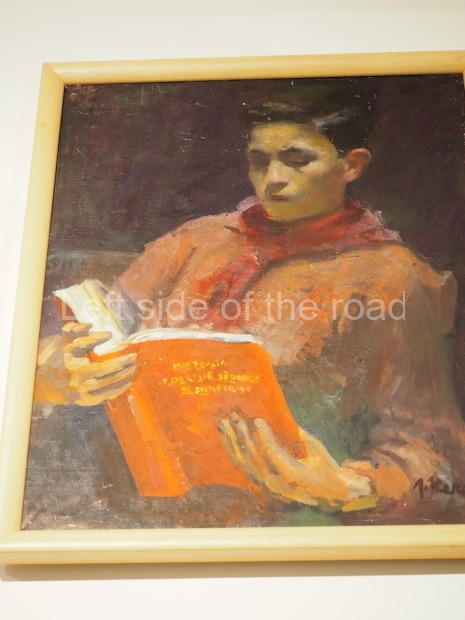

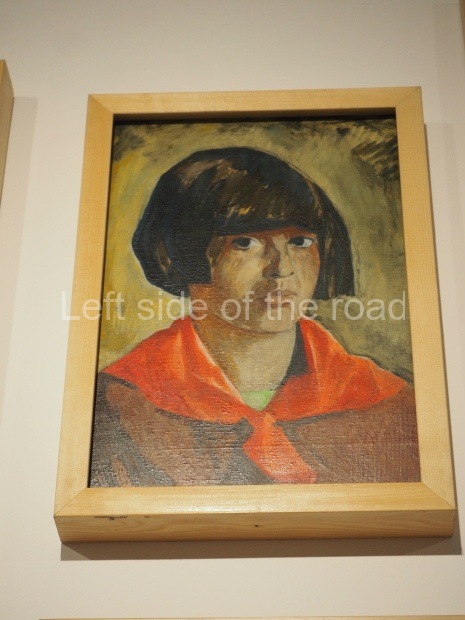

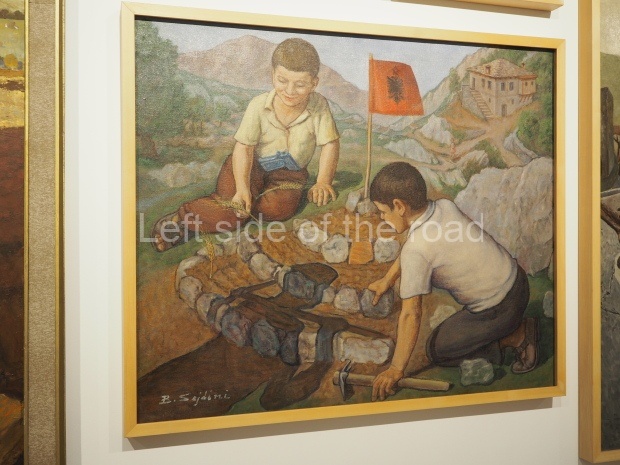

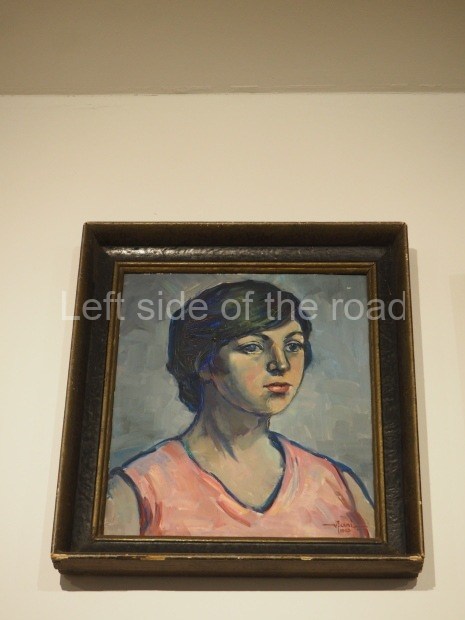

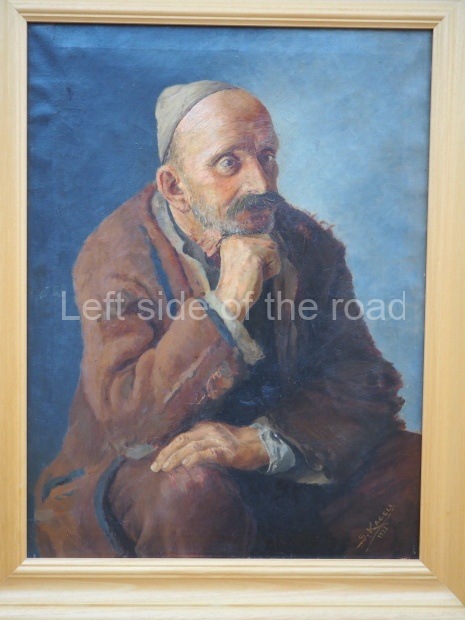

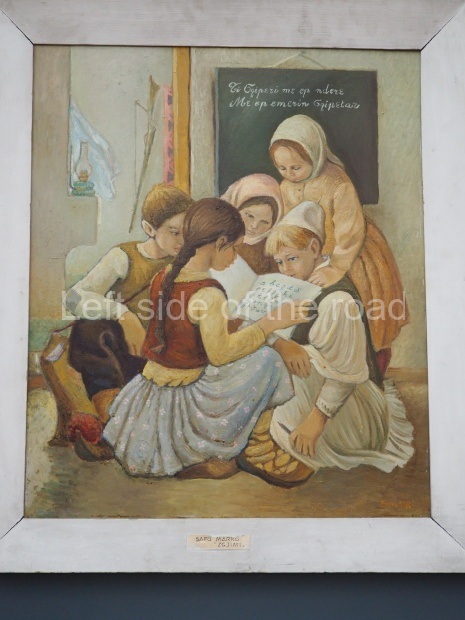

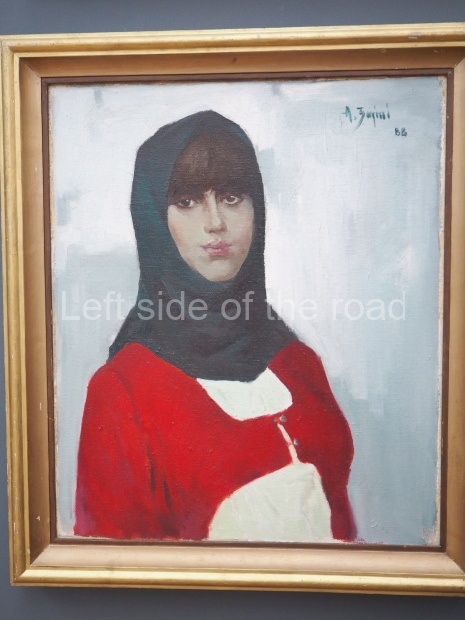

At present (September 2021) the ‘exhibition’ at the National Art Gallery in Tirana seems to be virtually everything that has been in storage over the last 30 years. But calling it an exhibition is a bit of a misnomer. The word exhibition gives the impression that a bit of thought and consideration had been put into the mounting and display of a collection of art. That is supposed to be the art of a curator – although that has been neglected in this case.

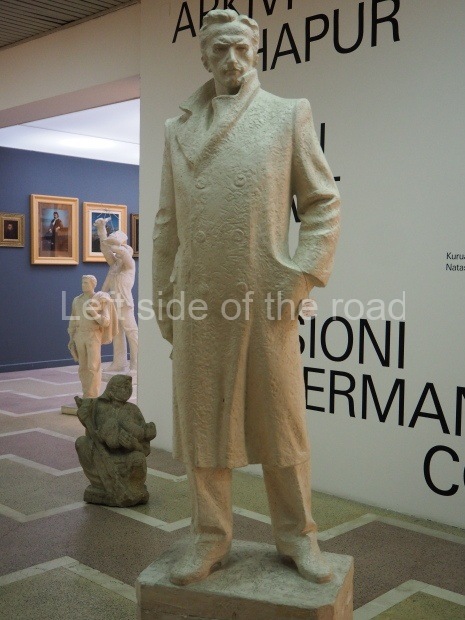

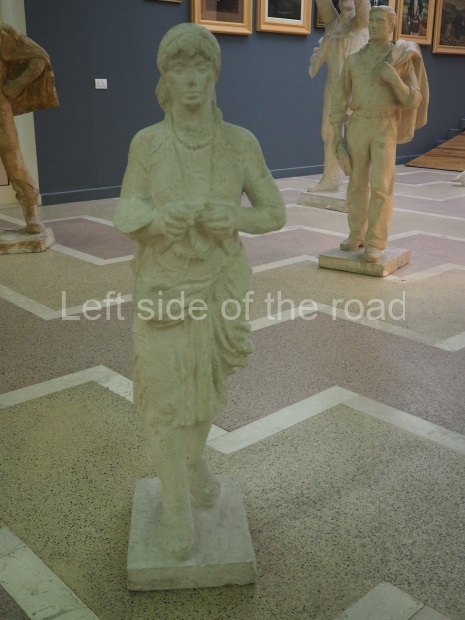

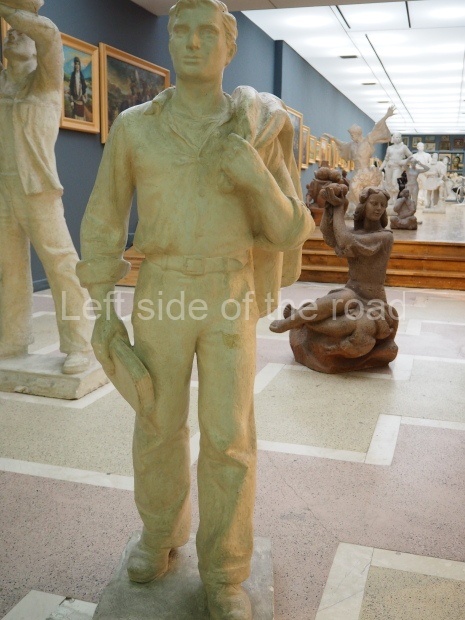

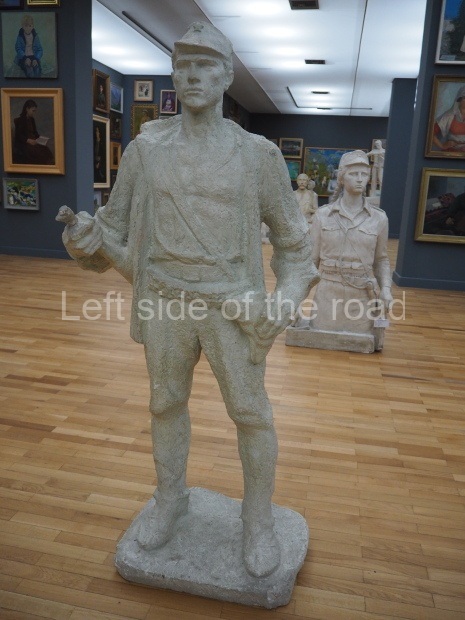

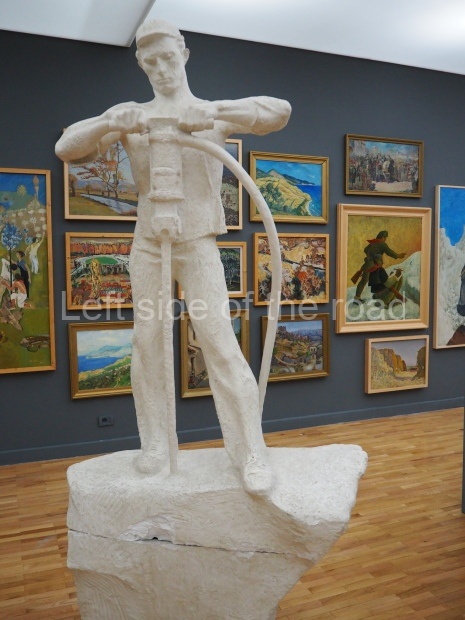

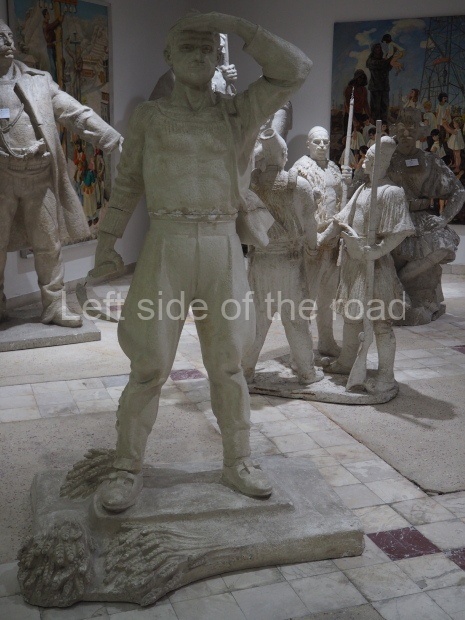

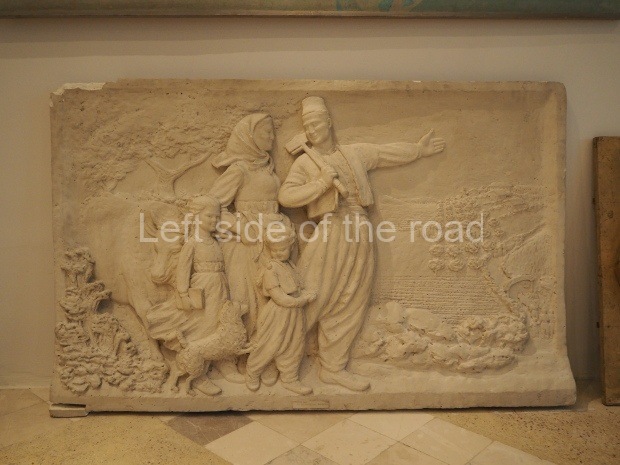

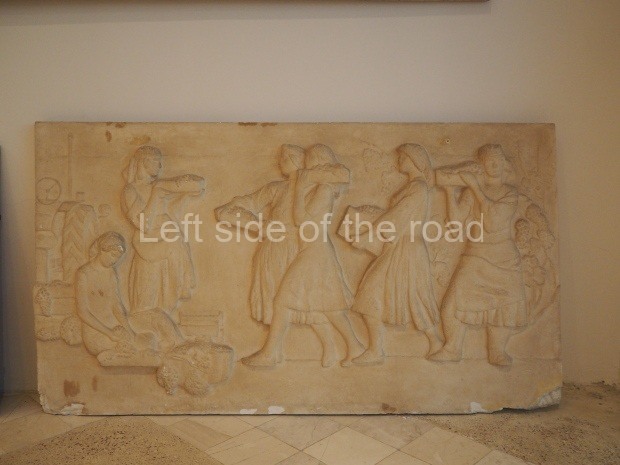

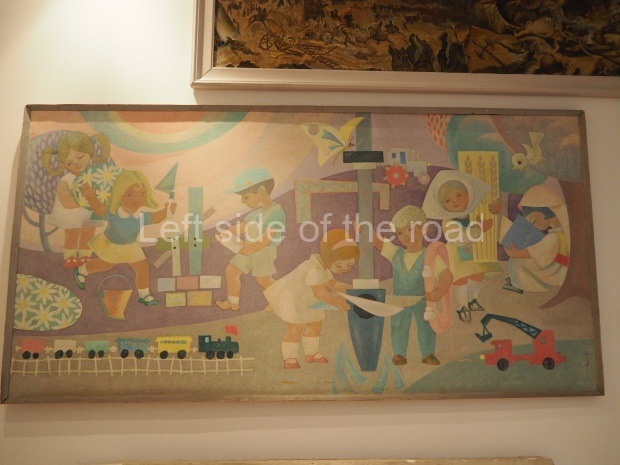

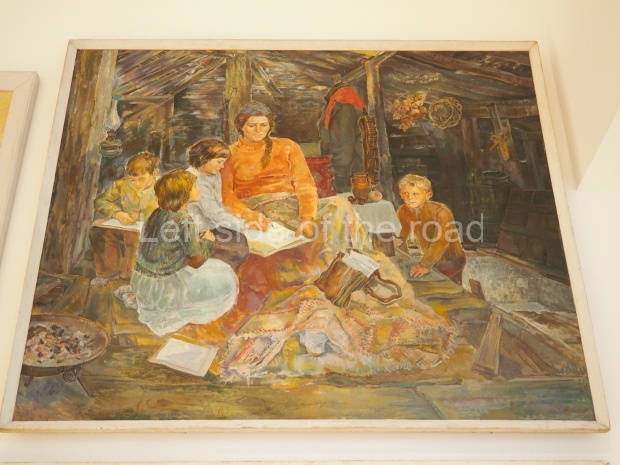

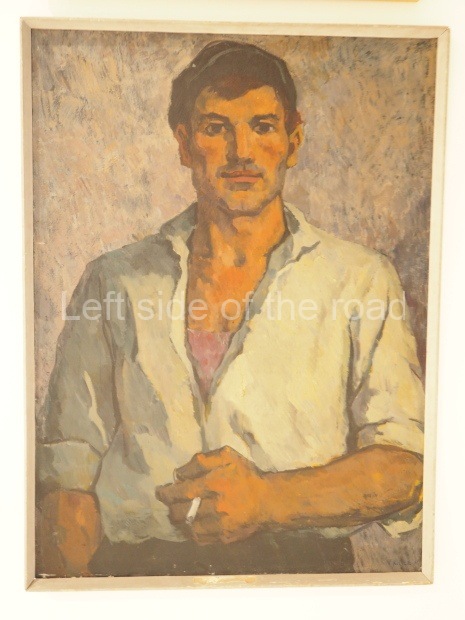

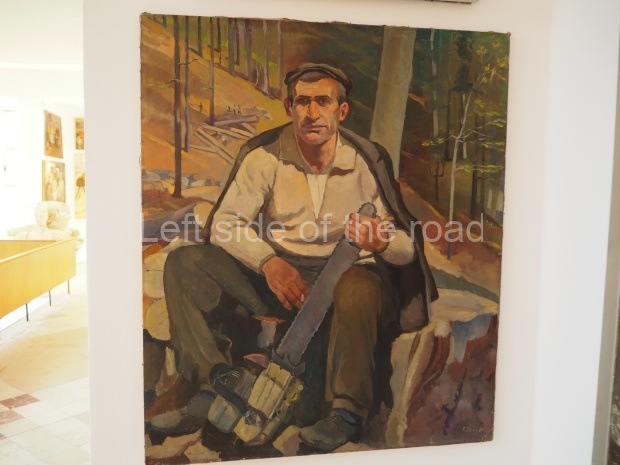

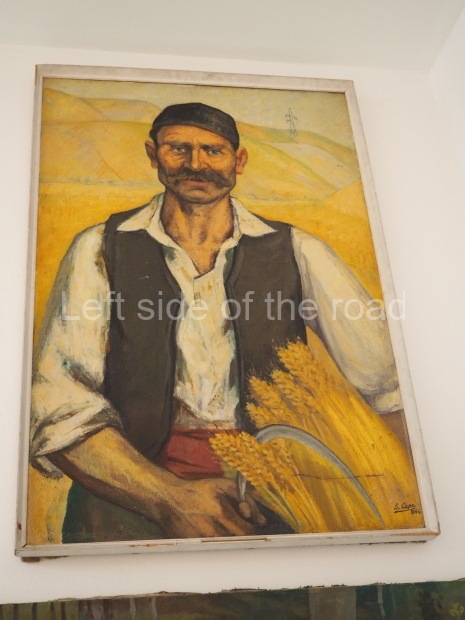

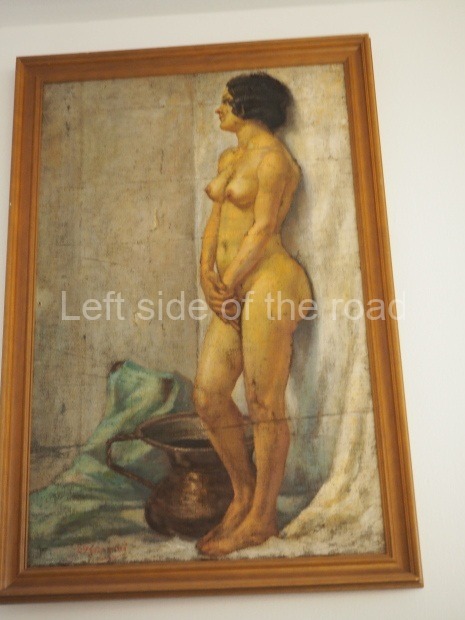

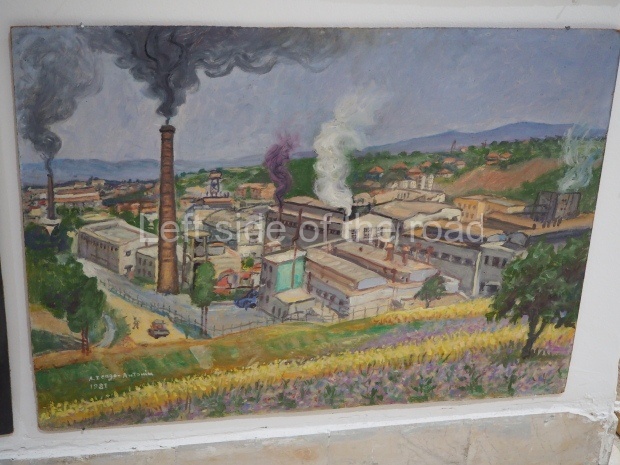

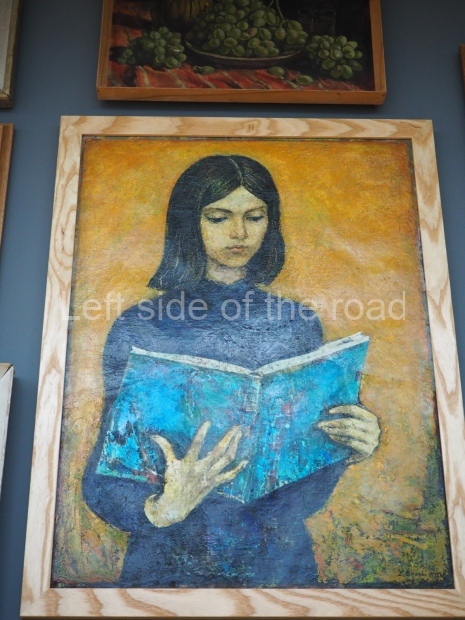

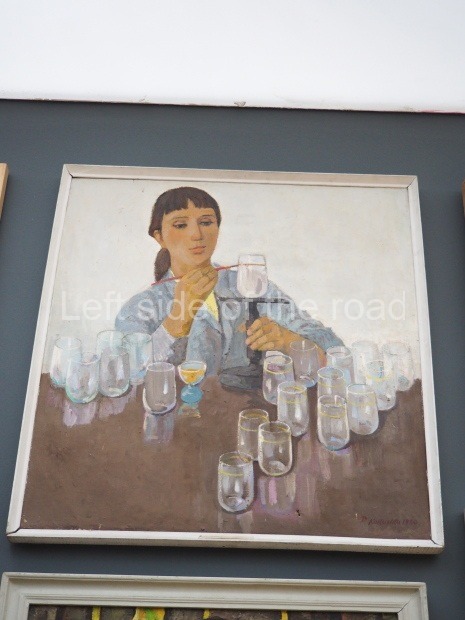

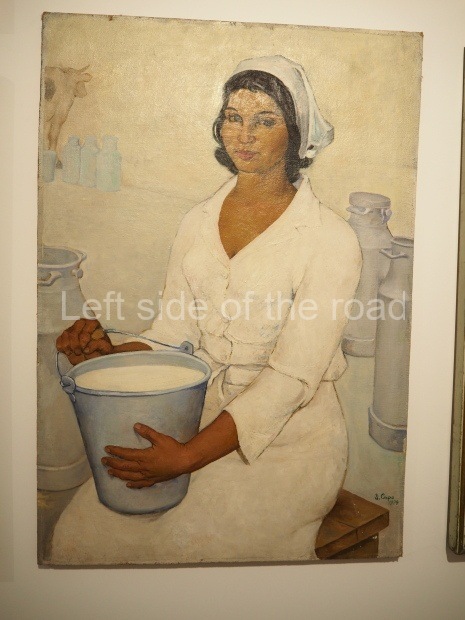

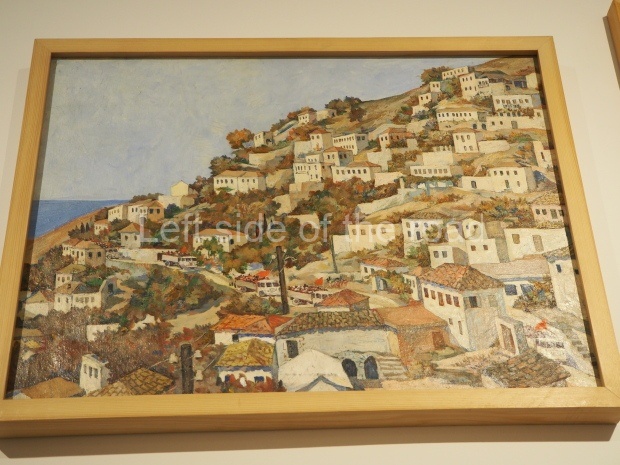

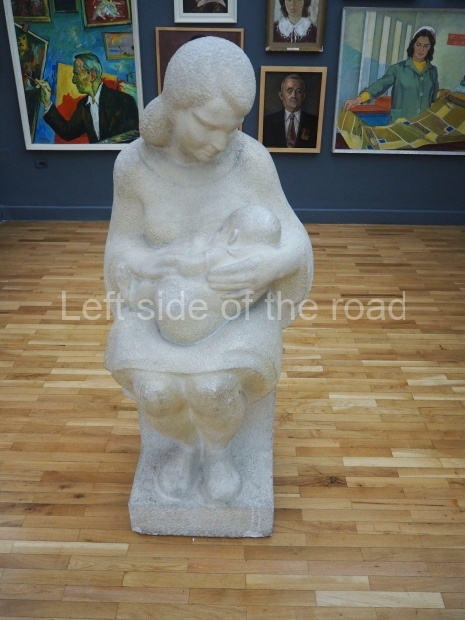

What is, in theory, a good idea – and something welcomed by anyone with an interest in the art of the Socialist Period in Albania – just turns out to be a mess. Virtually all available wall space has been used to mount the pictures and the sculptures take up virtually all available space on the floors.

But its all placed without any context, without any information, without any chronology, without any order or logic.

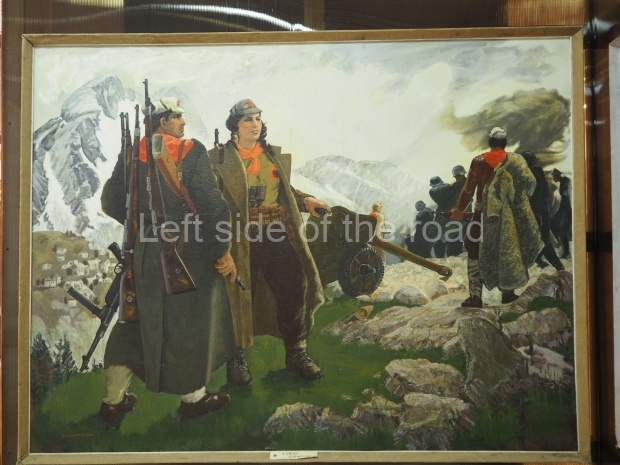

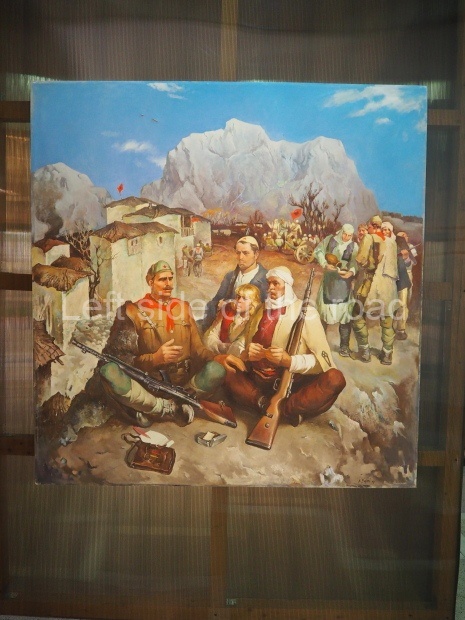

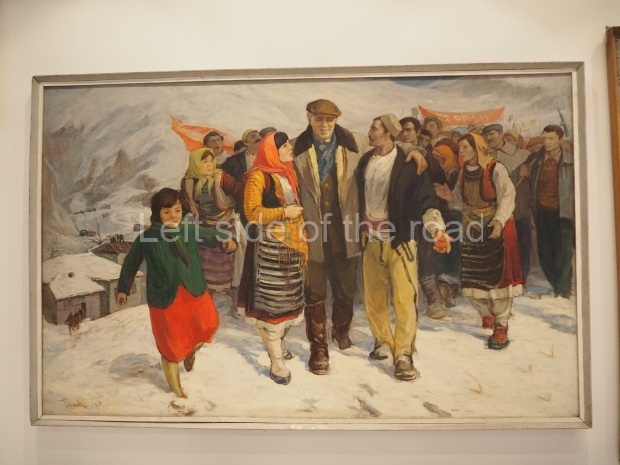

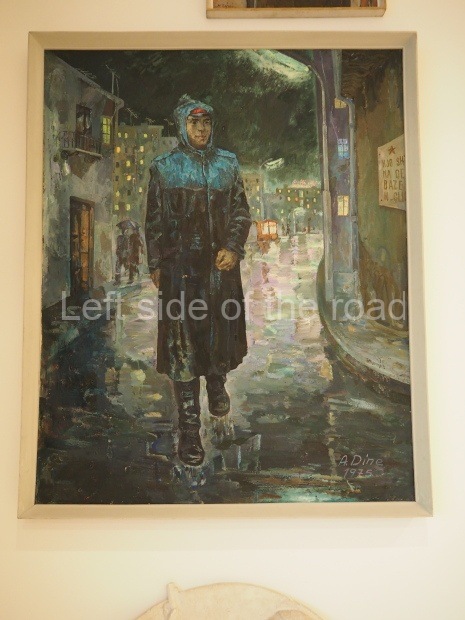

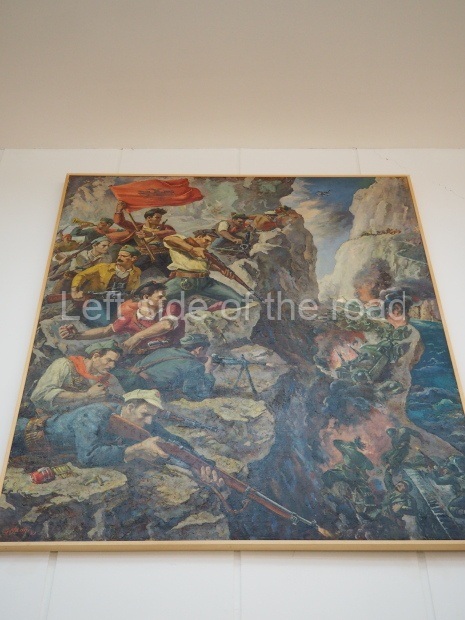

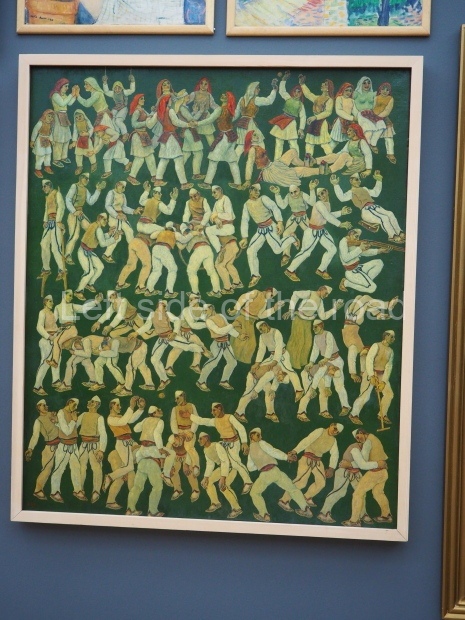

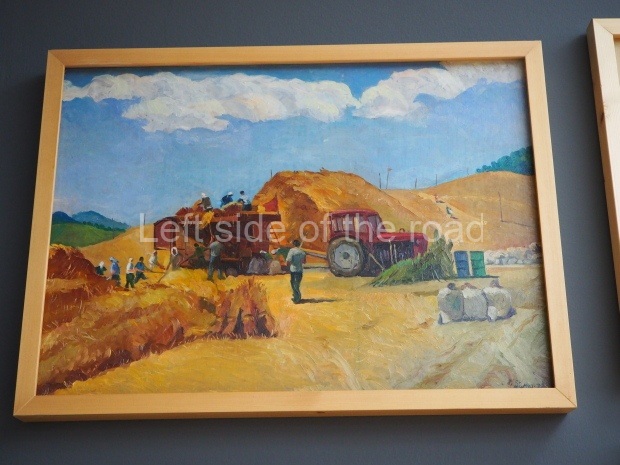

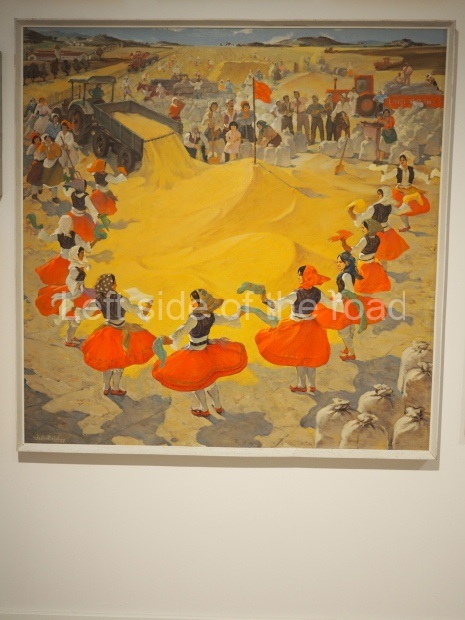

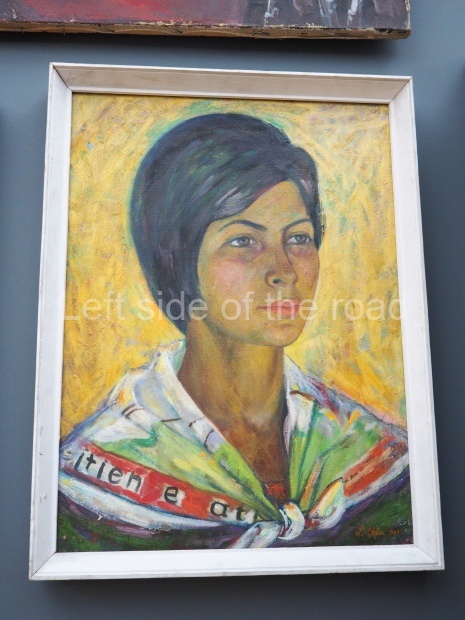

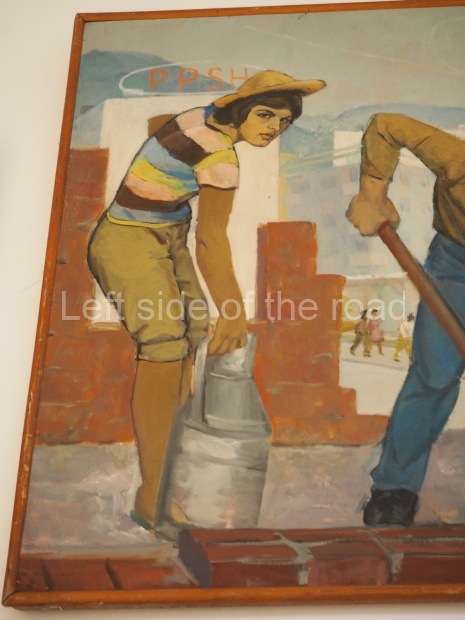

Paintings of pre-revolutionary times are displayed next to some of the last paintings produced under socialism. The works of particular artists can be found anywhere on the two floors which the exhibition occupies. It’s so chaotic that you are never able to understand any development in the ideas of socialist realism in what was Albania’s Cultural Revolution – which started at about the same time as the more famous one in China (the mid-60s) but which lasted longer, going into the 1980s.

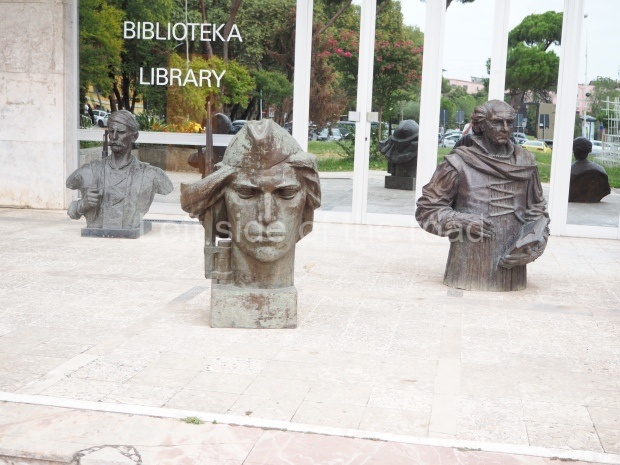

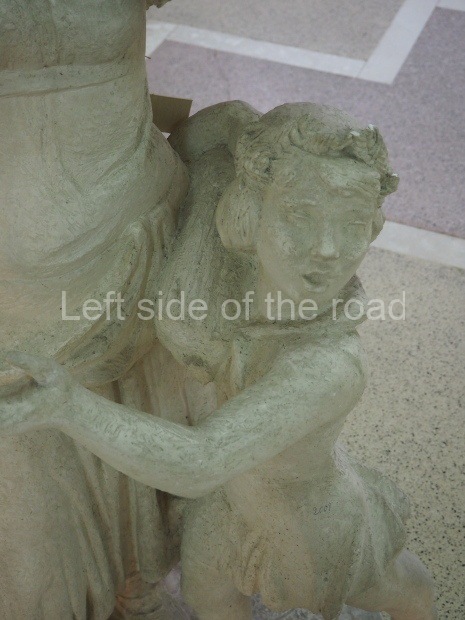

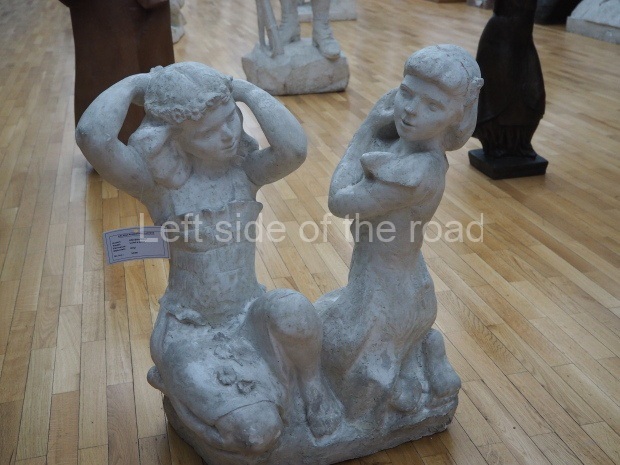

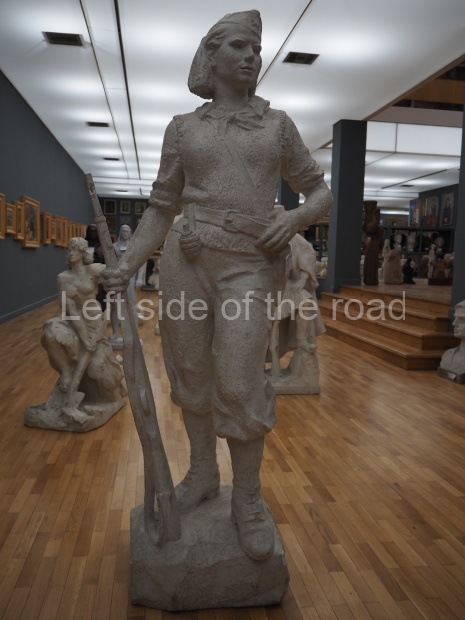

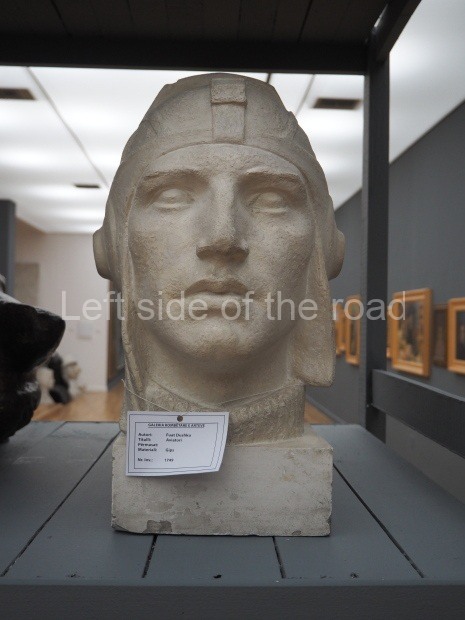

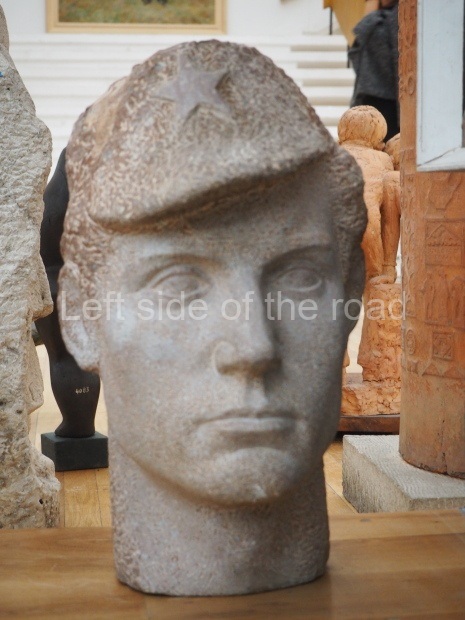

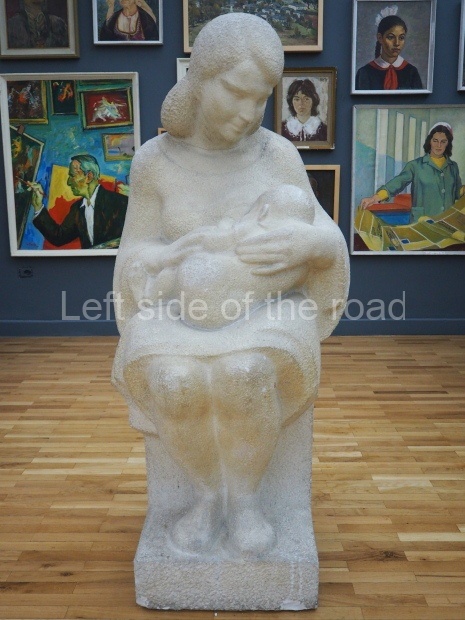

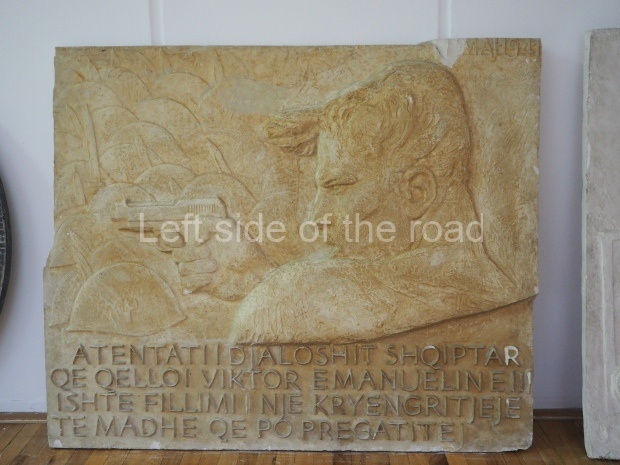

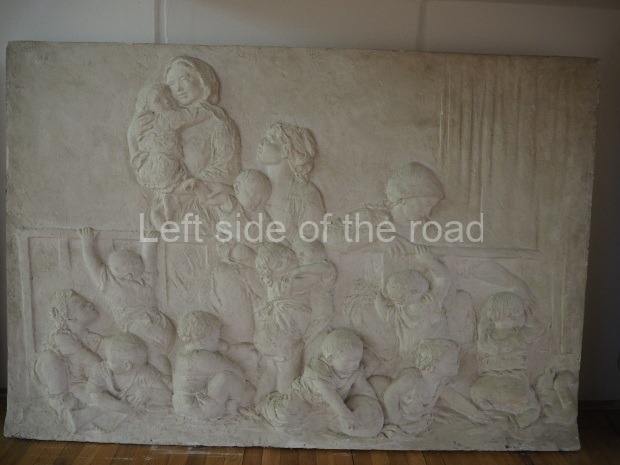

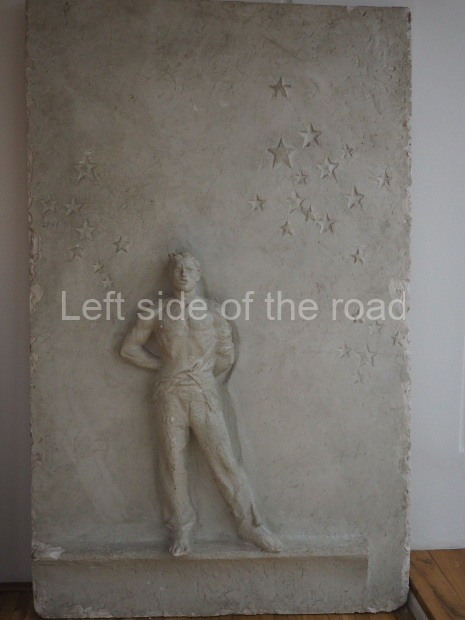

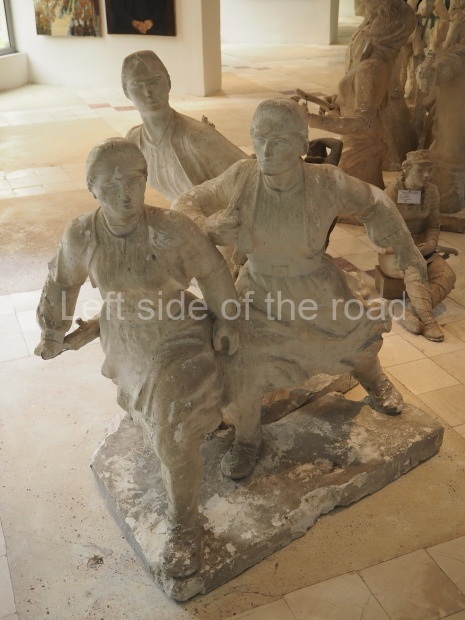

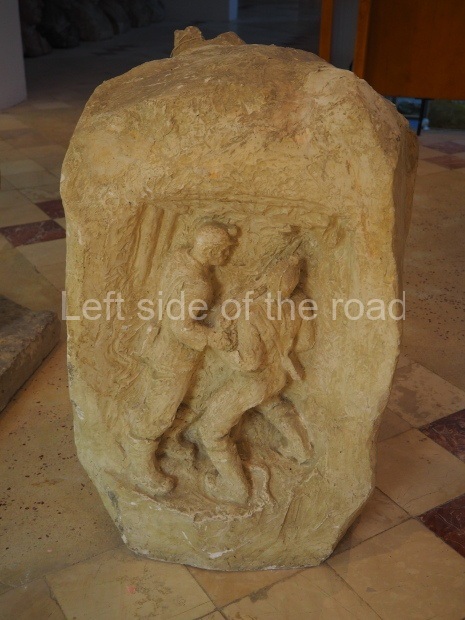

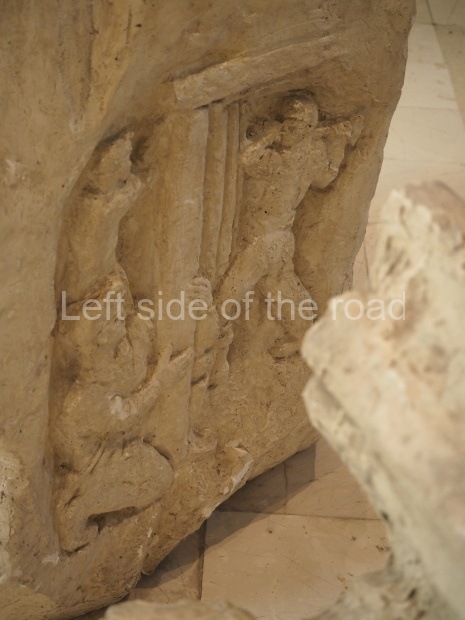

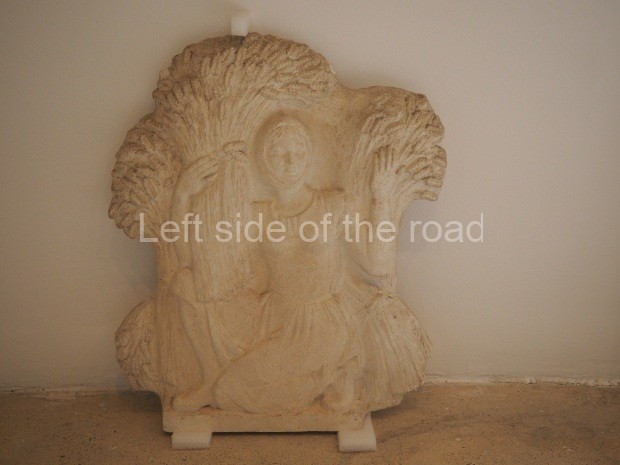

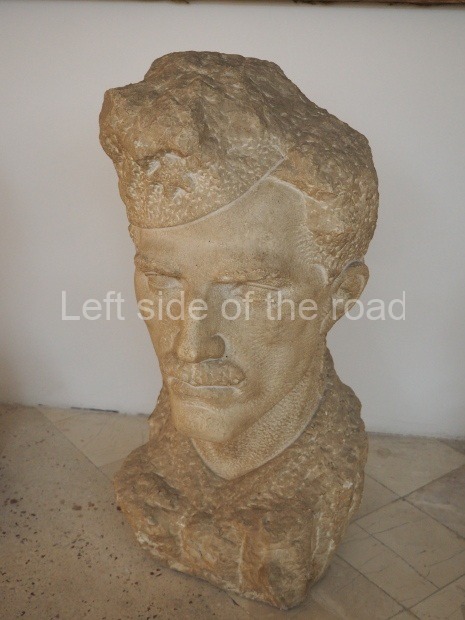

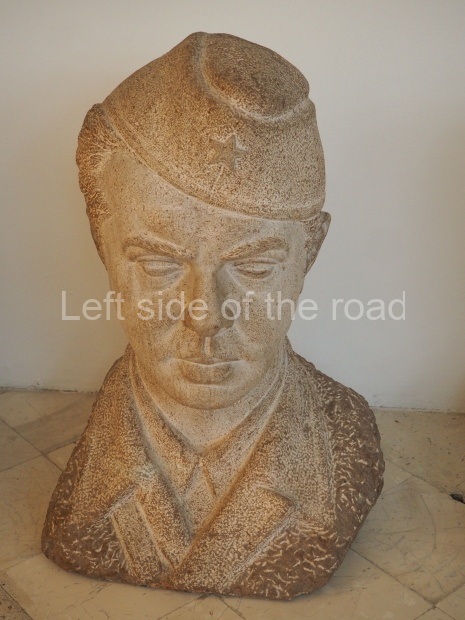

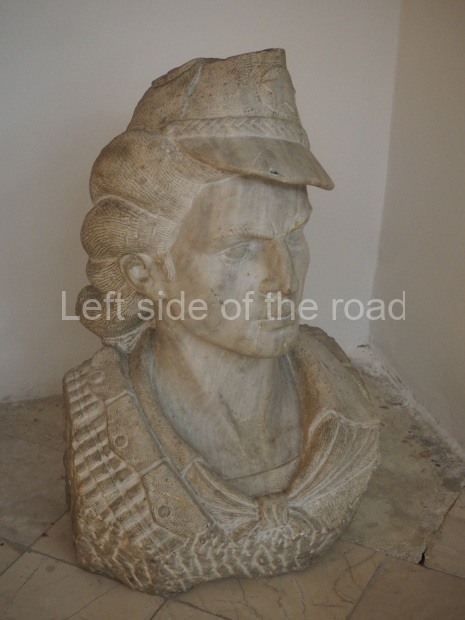

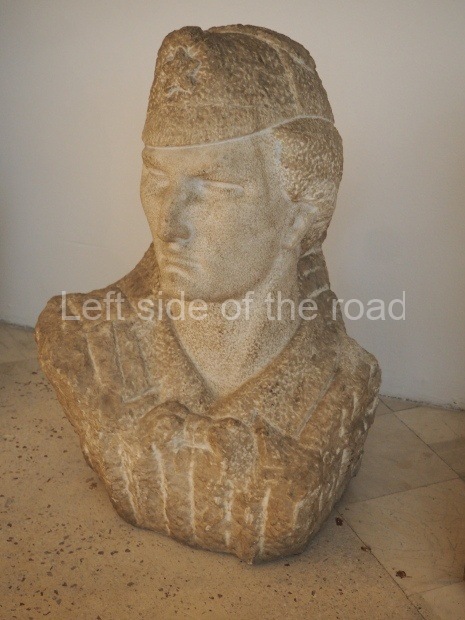

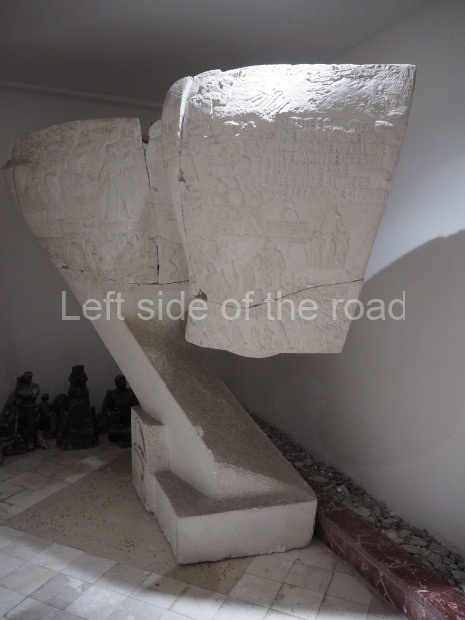

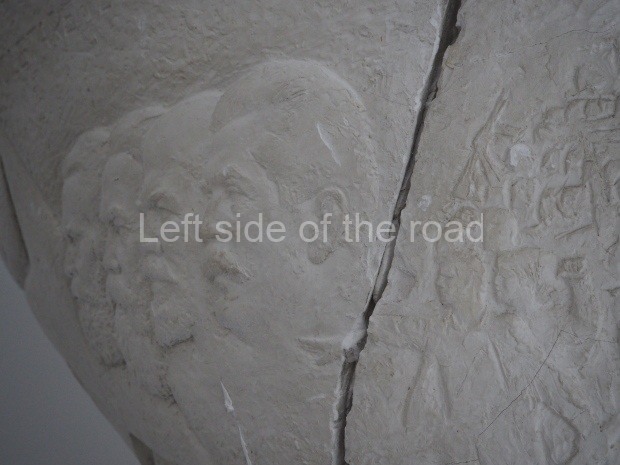

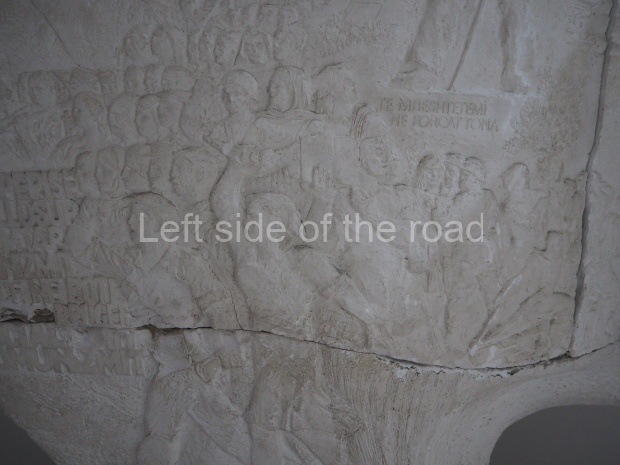

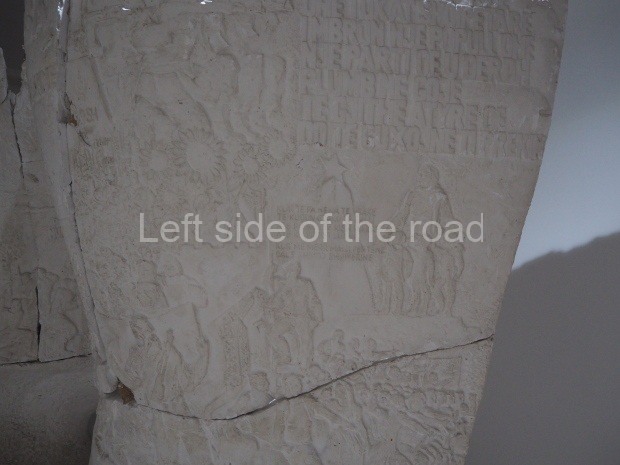

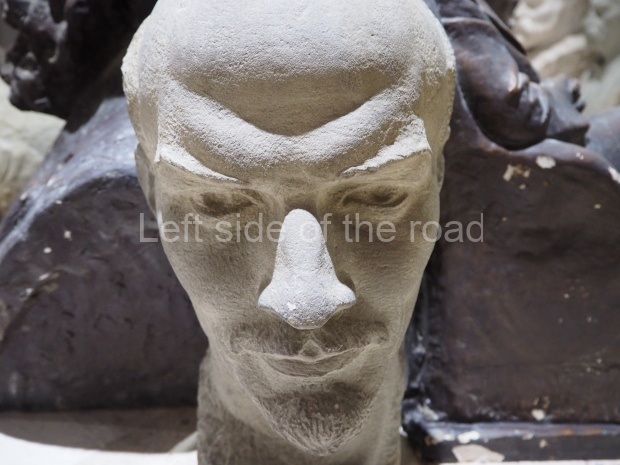

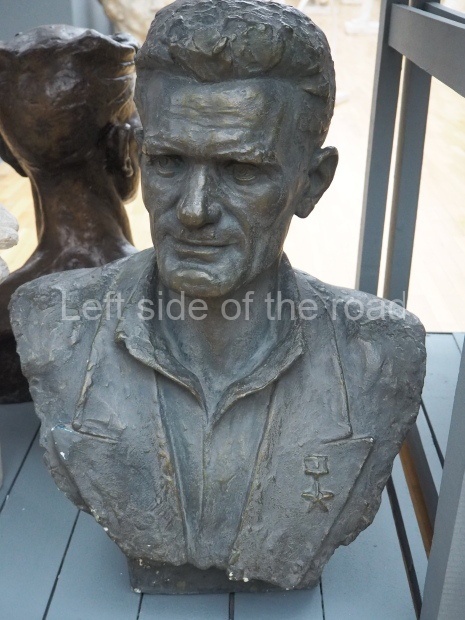

This is the situation with the paintings but this is mirrored with the sculptures. Many are ‘displayed’ on the same storage racks that would have been used in the building’s basement, many more are just placed on the floor. This means you can’t appreciate any one sculpture in itself as it is so close to another, either to its side or behind. A number of the sculptures have an original label attached so you get discover the name of the artist and work title but little more. The fact that so many of them have even those labels missing gives the impression that even the gallery itself probably doesn’t know for certain the artist, date or subject matter.

And you can’t appreciate a sculpture if the only way to get a decent view is to lie on the floor (if that was indeed possible without knocking over its neighbour).

To add to the ad hoc feel of the exhibition a number of the paintings are lacking a proper frame and are just as they would have been after the artist had completed the task.

One important matter is clear from the taking of these works of art from storage is that no one employed by the art gallery really cares at all about this part of the country’s heritage. As with the lapidars throughout Albania many of the sculptures show signs of damage, presumably due more to lack of care rather than deliberate cultural and political vandalism but the results are the same.

The pictures in the gallery/slide-show below are in an as chaotic order as the exhibition itself. Some are not as I would have liked as the lighting was so harsh in places that to avoid the reflection the photo had to be taken from an angle. Also the pictures that were mounted high up on the walls have obviously been taken from below and hence a certain amount of distortion. And the general ‘crush’ of the exhibits prevents any true appreciation from a distance.

One of the reasons for making such an extensive record of this exhibition is I fear that these objects are very unlikely to be ever displayed again – certainly as a whole representation of Socialist Realist Art. My greatest fear is that some of the more seriously damaged sculptures will move from the exhibition space to the nearest skip to end up in landfill. The State won’t pay for the time and effort that would be needed to return them to something akin to their original state and as such will just take up valuable space. The same could be the fate of the damaged paintings.

These fears are reinforced by decisions which now seem to being made in some other aspects of the depiction of the country’s Socialist past. Not only are those examples of socialist art that have for many years formed part of the permanent exhibition in the sme gallery now covered – for some inexplicable reason – but also the rooms devoted to the anti-fascist struggle in the National Historical Museum are presently closed to the public.

Perhaps the answer will be partly given when The Albanians (the name given to the huge mosaic on the facade of the Historial Museum) which is currently undergoing ‘restoration’ is unveiled. The word ‘restoration’ implies repairing and returning to an original state. However, the mosaic had much of its political significance removed by one of the original five artists (Agim Nebiu) sometime at the beginning of this century – still haven’t been able to find out exactly when – who was willing, for his equivalent of ‘thirty pieces of silver’, to remove the stars from the flags carried by the central characters. A few red stars remained after this act of political and artistic vandalism but whether they will survive the present ‘restoration’ is another matter.

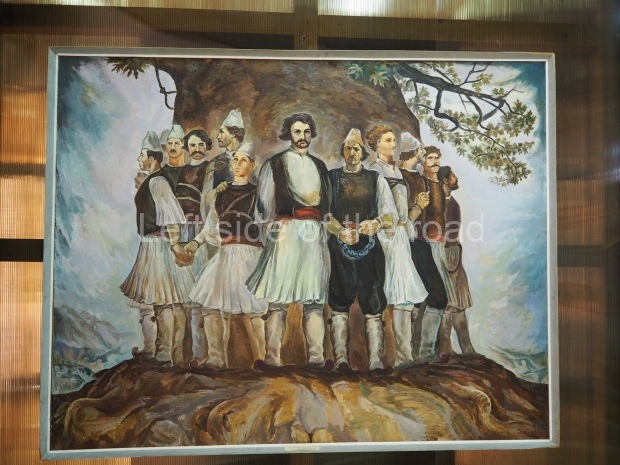

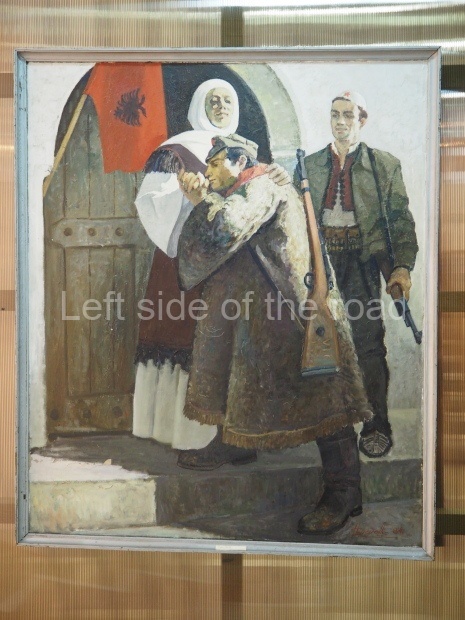

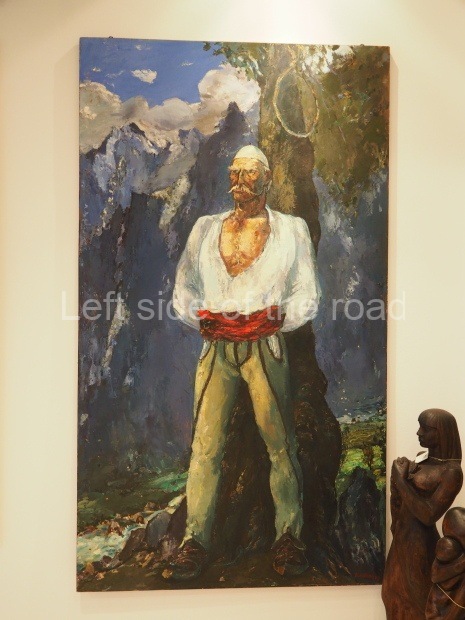

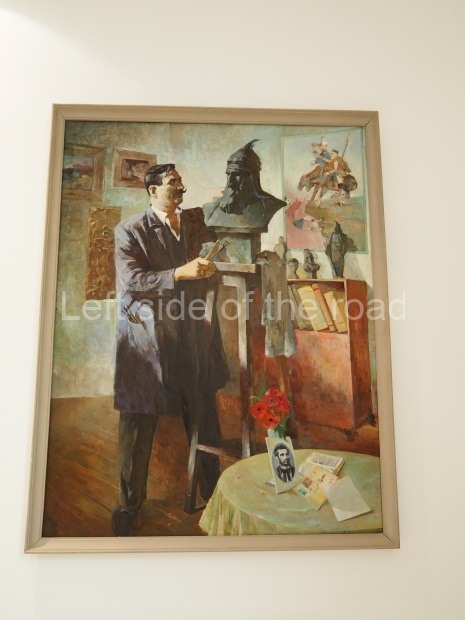

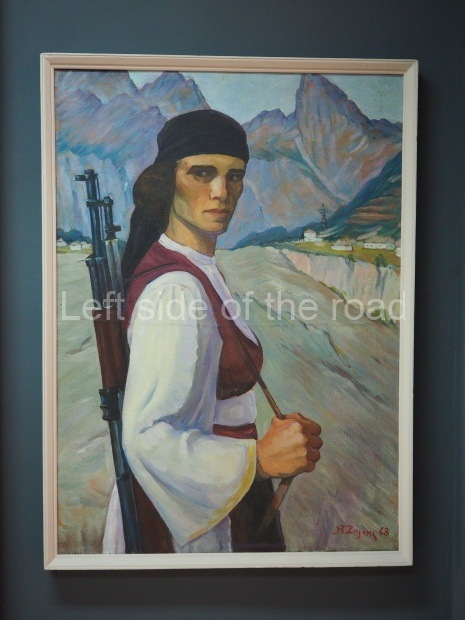

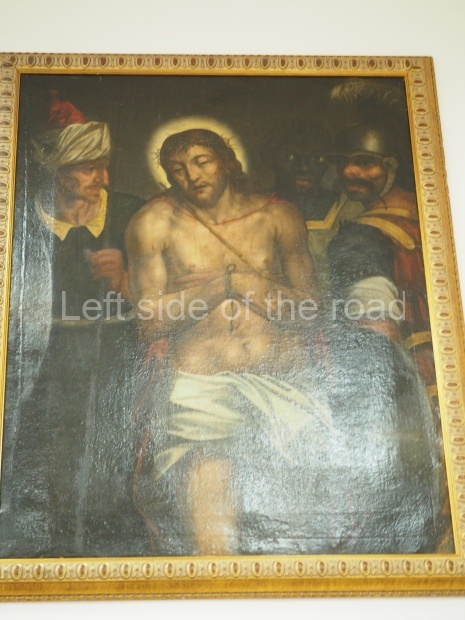

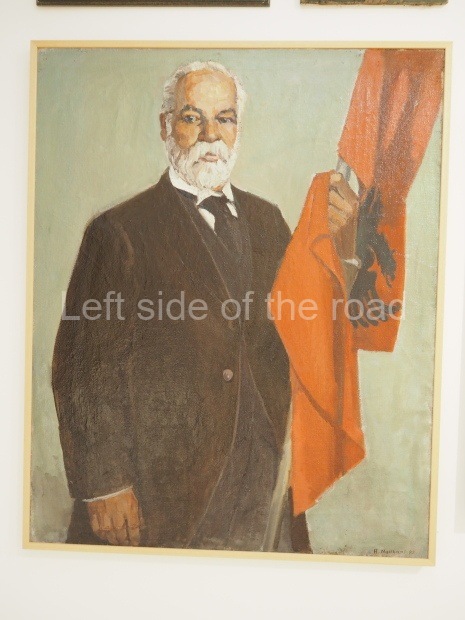

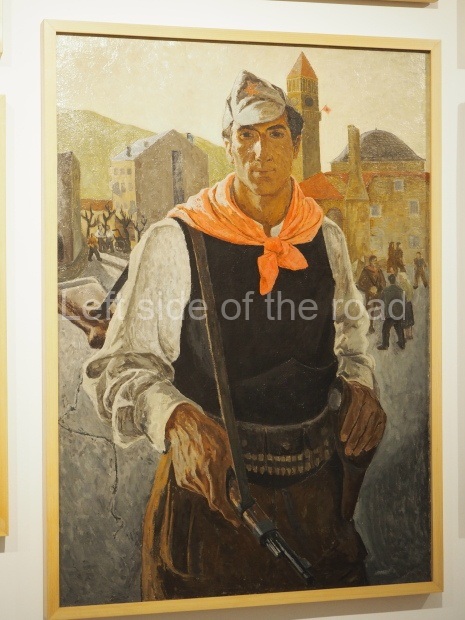

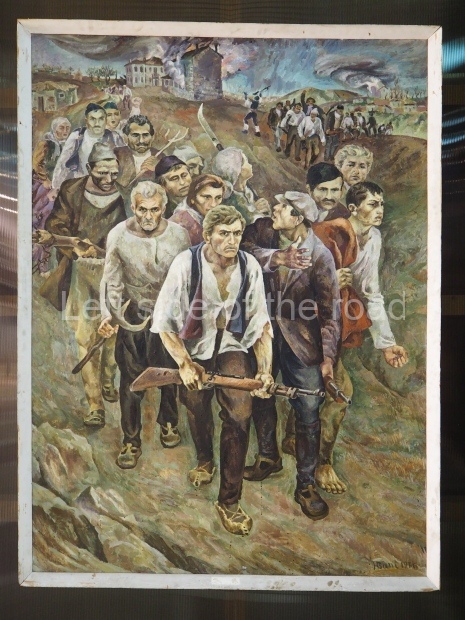

As well as the examples of socialist realist art there were a considerable number of paintings that represent the past struggles of Albanians for independence. Such imagery played a role during the Socialist period as the country was constantly under threat of invasion (or intervention) from either neighbouring Yugoslavia or any of the imperialist nations who couldn’t reconcile themselves to the fact that this small, yet strategically situated, Balkan country had chosen a future not under the control of capitalism.

But even during the 1970s and 1980s this glorification of a 15th century aristocrat was a little over the top. Banging the nationalist drum whilst attempting to construct socialism will always have its dangers as that nationalism can distract from the principal task in hand. And this very nationalism, that was used to reinforce the idea of independence under socialism, is what the present capitalist leaders of the country rely on to give them some sort of historical credibility – as they certainly have no interest in independence, fighting each other in deciding to which imperialist force to sell the country.

What to look out for

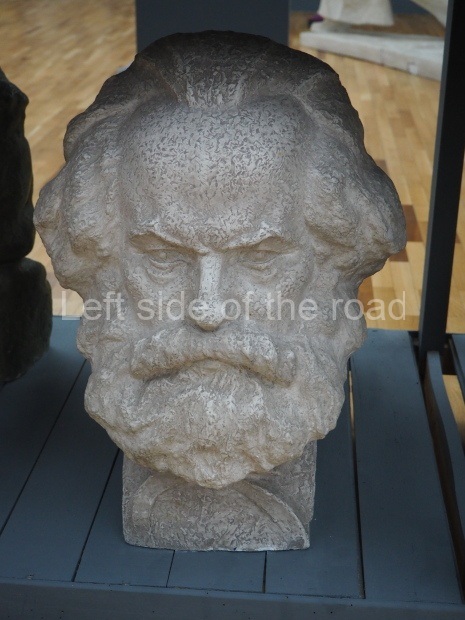

- a bust of Chairman Mao Tse-tung

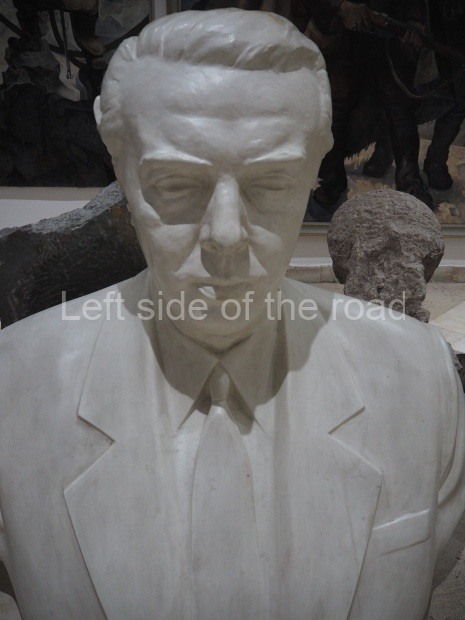

- busts of Karl Marx, Frederick Engels, Vladimir Ilyich Lenin and Joseph Stalin – most of these would have previously been displayed in the Lenin and Stalin Museum (the building now used as a government office, next to the big, new mosque in the centre of Tirana, just behind the Art Gallery itself)

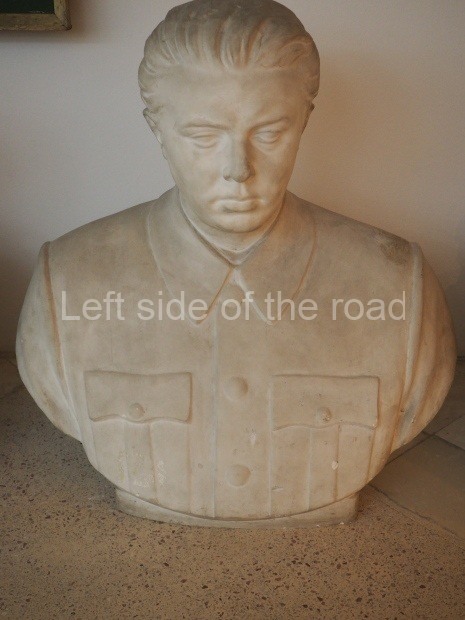

- at least four busts of Comrade Enver Hoxha, all in ‘good’ condition and without having been vandalised (as is the example in the ‘Sculpture Park’ at the back of the building, on the right hand side)

- maquettes of a number of sculptures that were later made into much larger structures which can still be seen in various parts of the country such as the ‘Thirsty Partisan’ (ALS10) and Pickaxe and Rifle – one of the sculptures in the ‘Sculpture Park’

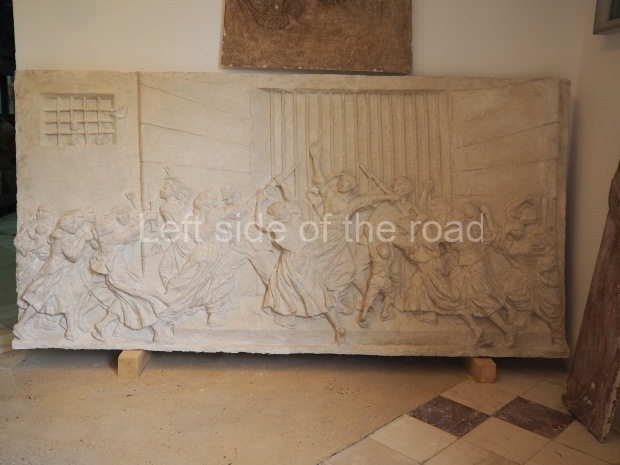

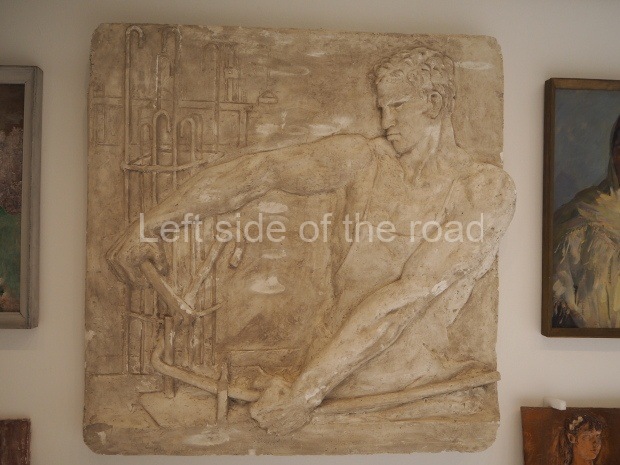

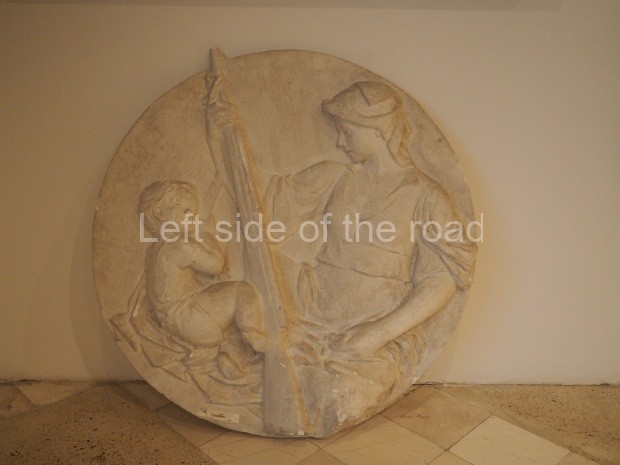

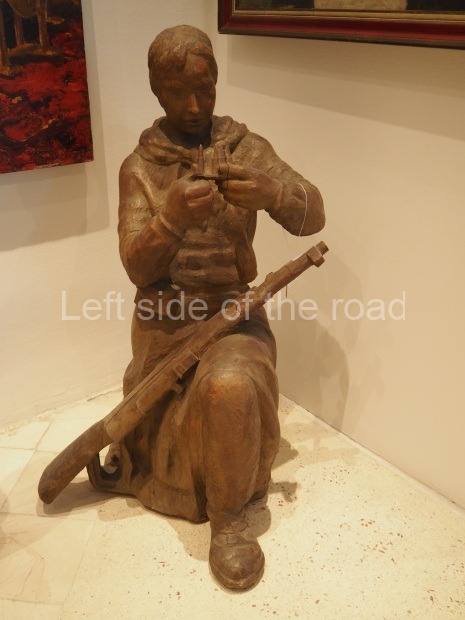

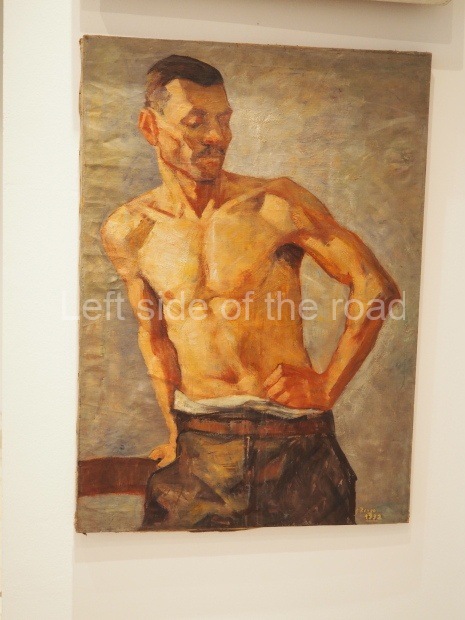

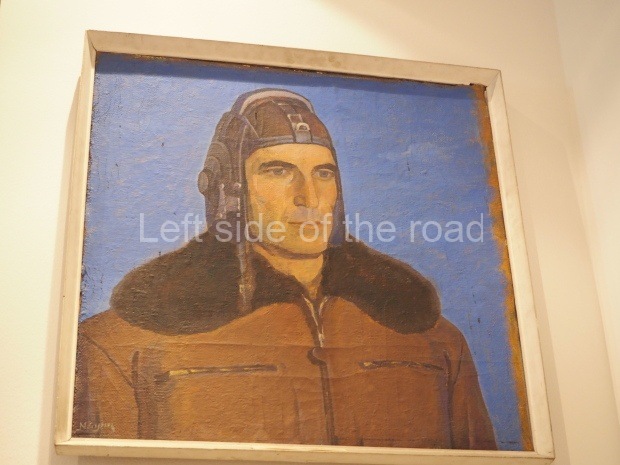

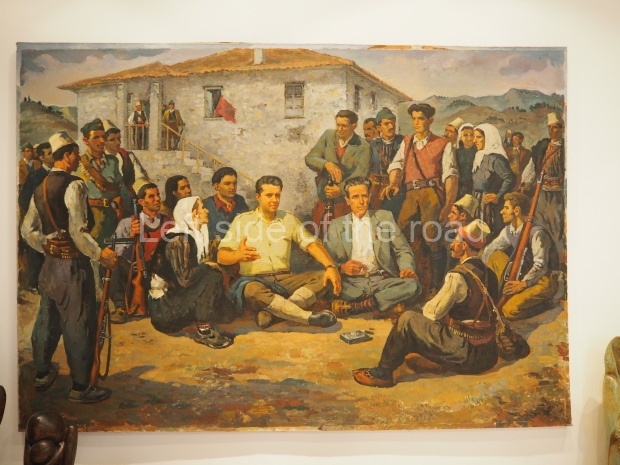

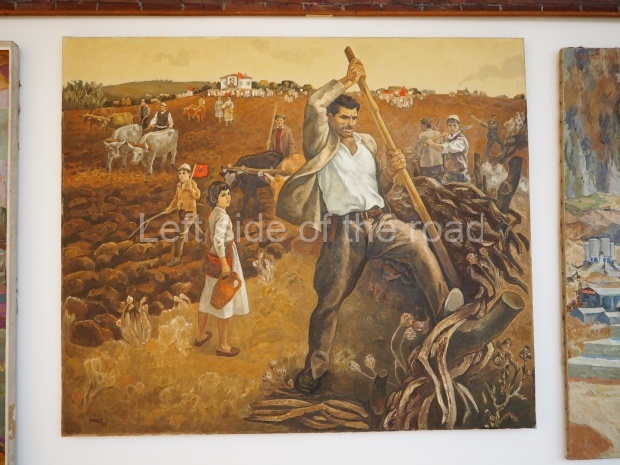

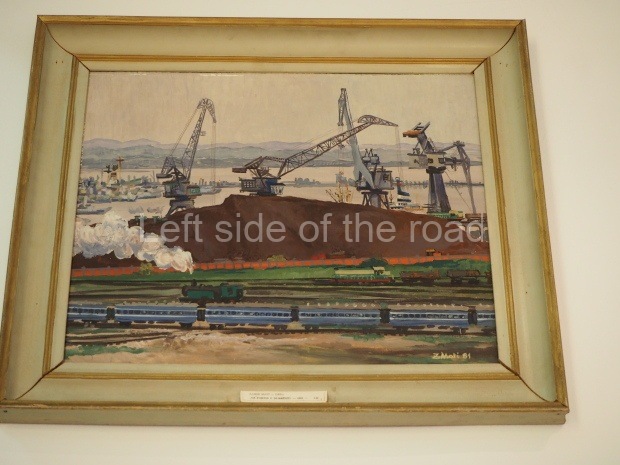

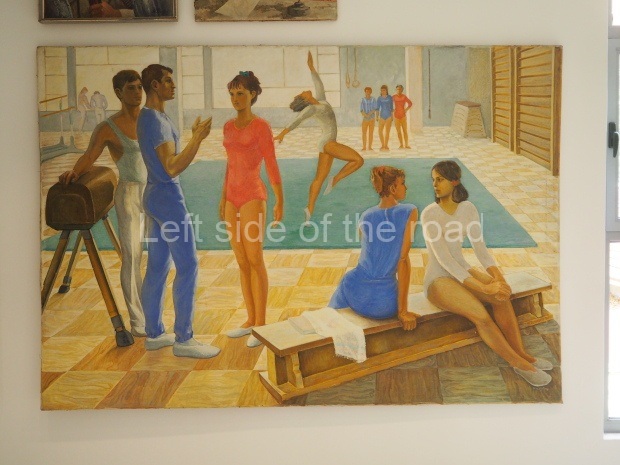

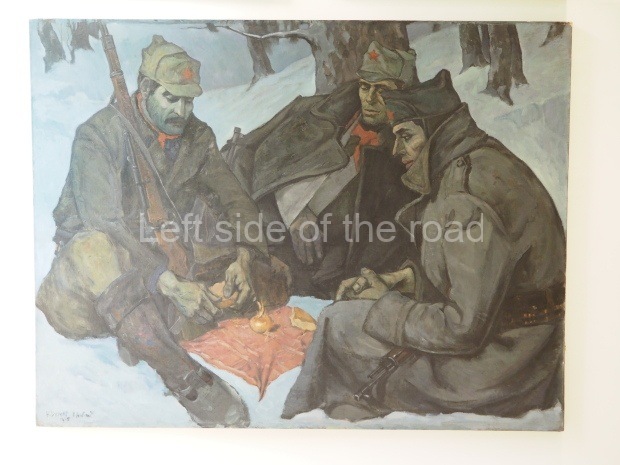

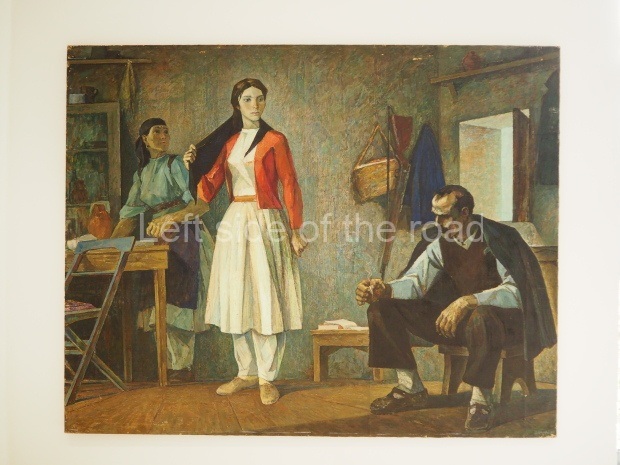

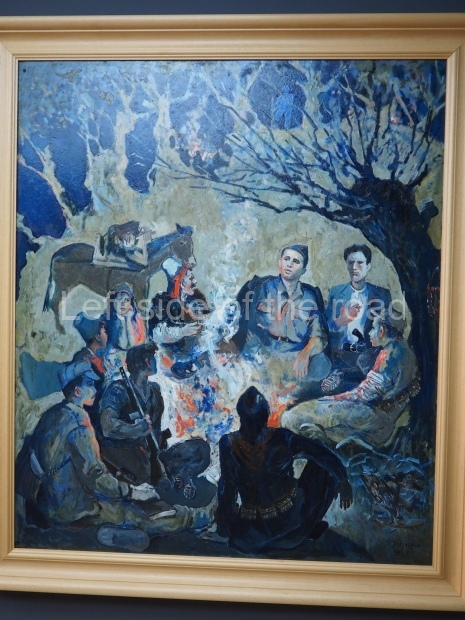

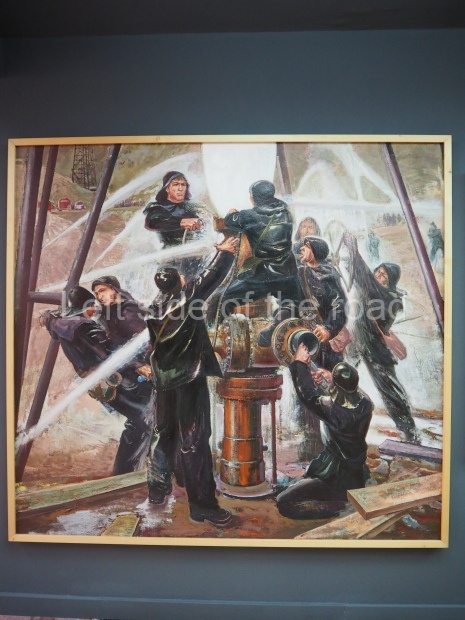

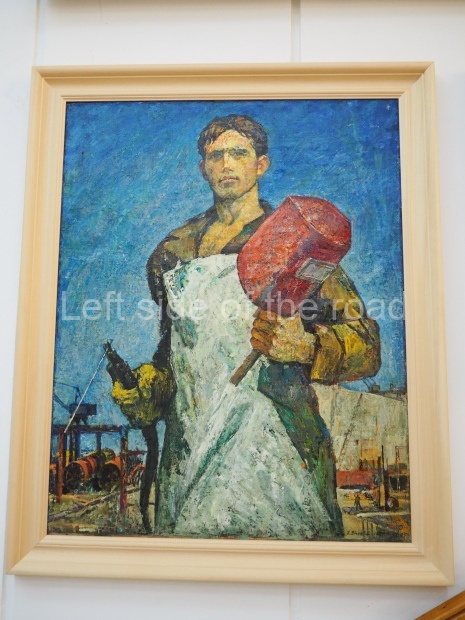

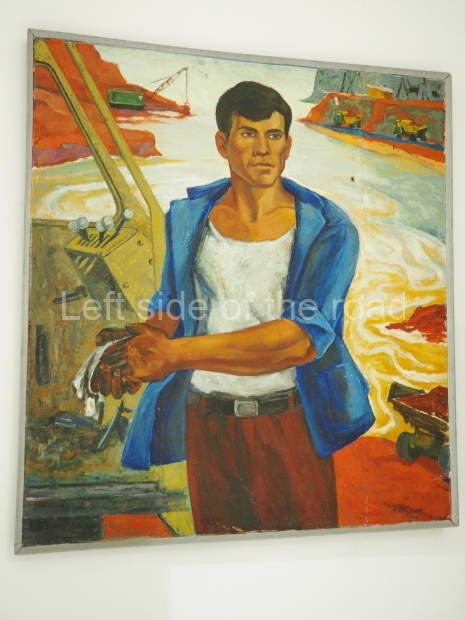

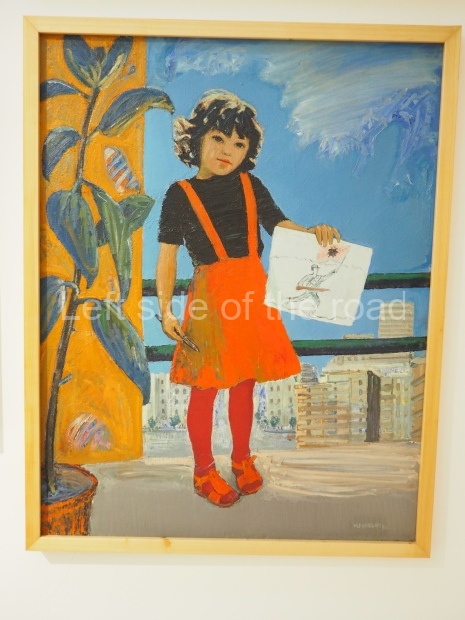

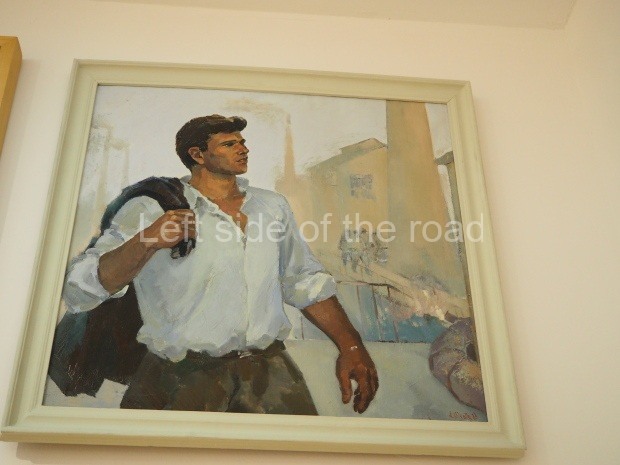

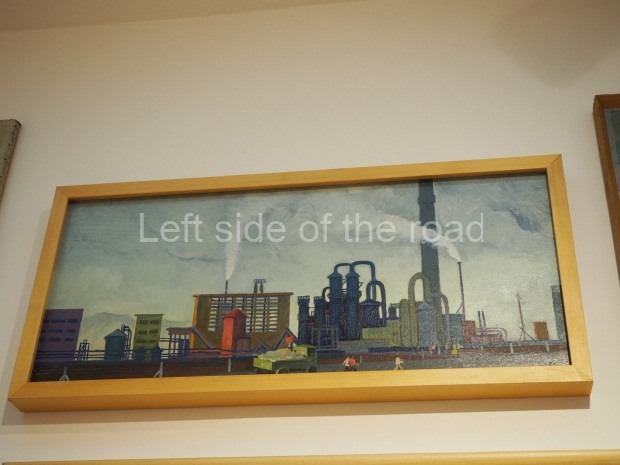

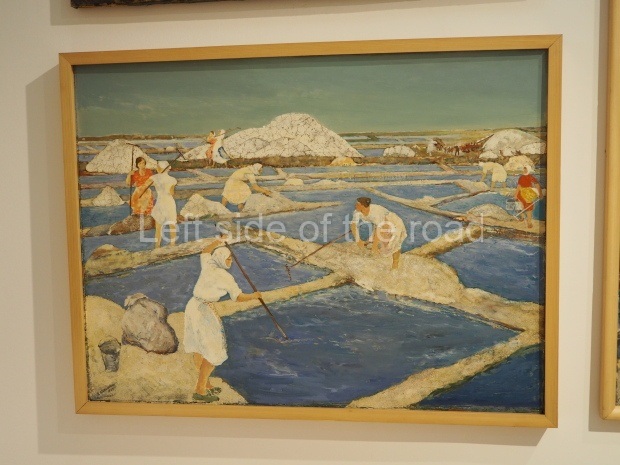

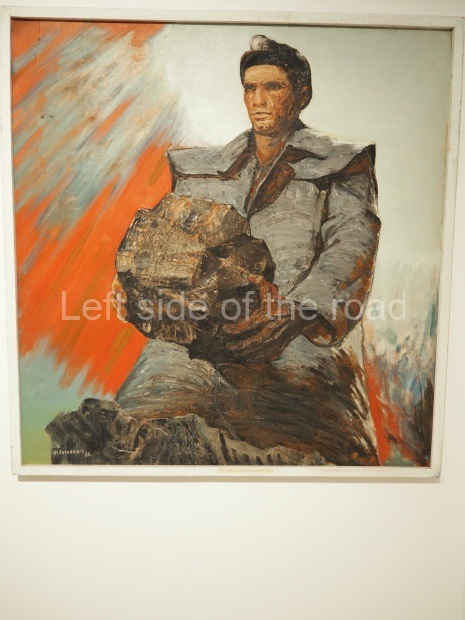

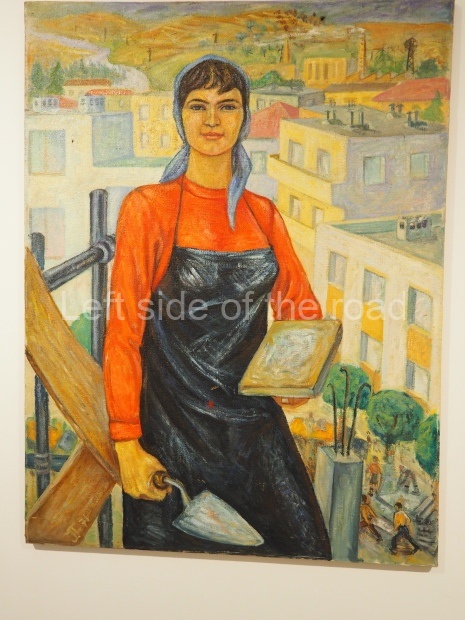

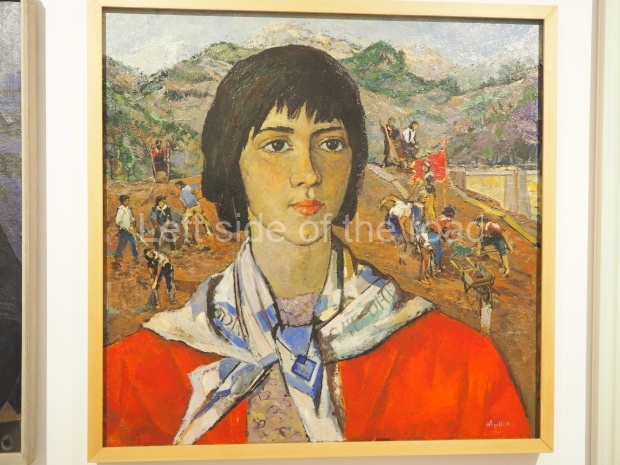

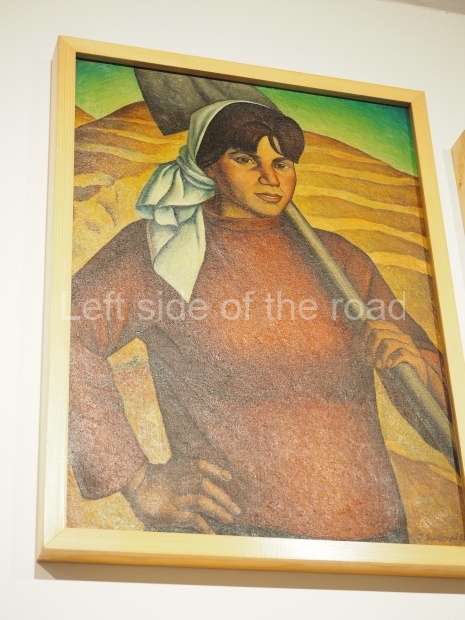

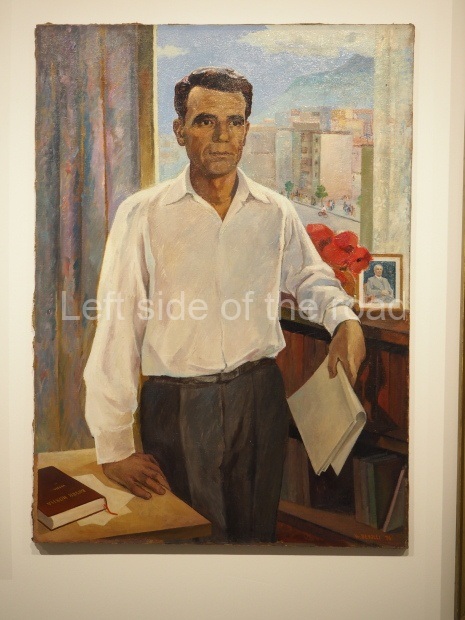

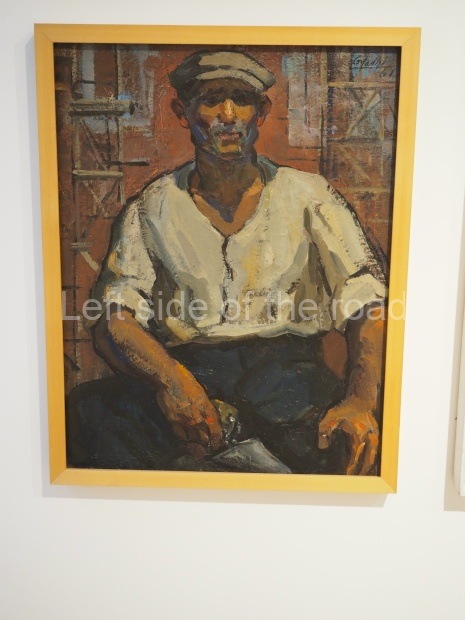

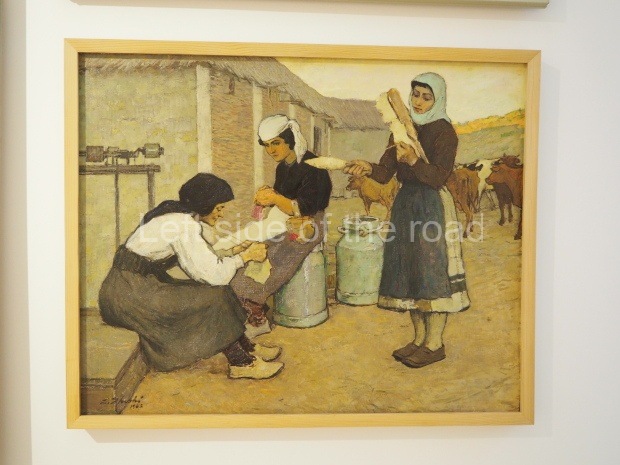

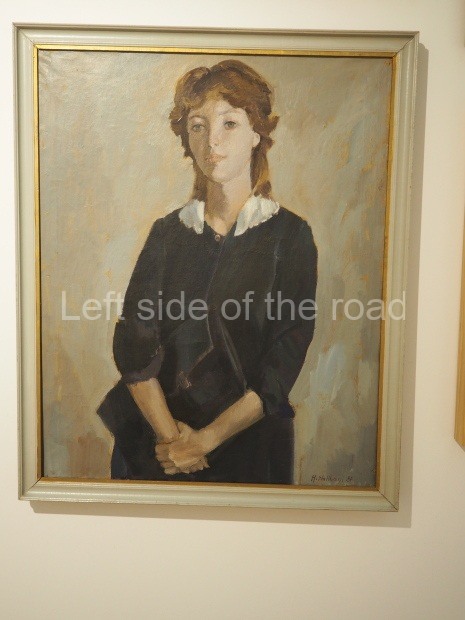

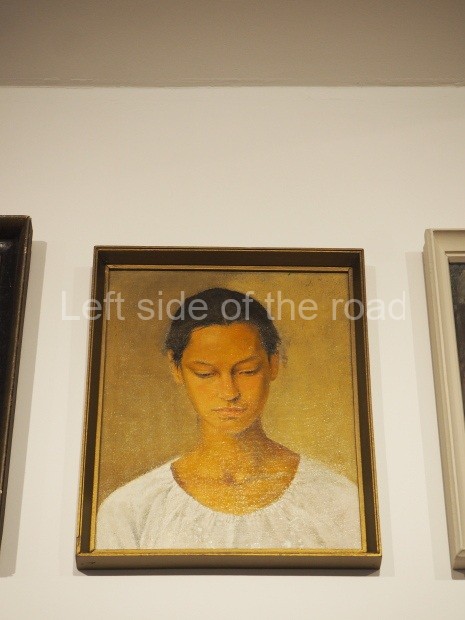

- those images show the lives of working people, using their efforts to create a different type of society to the one devoted to capitalist profit – the art that makes Socialist Realism so radically different (and advanced) than all the art that has gone before

- the many images, in both the paintings and in the sculptures, where women are presented as being armed and prepared to make the ultimate sacrifice in the achievement of victory against the Fascist invaders or in the construction of Socialism

- and generally the preponderance of ordinary working people in all the images rather than the ‘celebrities’ and the ‘rich and famous’ which dominate in capitalist society.

NB From the end of 2021 the gallery has been closed. I have no information about exactly why but there had long been signs of the need for structural repairs. When it will reopen I have no idea. There didn’t seem to be much activity when I was in Tirana in the summer of 2022. Neither do I have any idea of what will be exhibited. There is, I’m sure, a possibility that the items that were part of the permanent exhibition, works of Socialist Realist Art, might well be confined to the depths and the gallery will become a centre of decadent capitalist ‘art’.

Ukraine – what you’re not told

Well, you may be right about that, for little appeared to be going on this week ((the one which ends up with oil being wiped over the British head of state. But the statutes of Lenin and Stalin, at least, have moved from the gallery’s back yard to the (impeccably kept) front garden of Mehmet Shehu’s house, now guarded by security men. Makes of that what you will….

Thanks for the update of the whereabouts of Lenin and Stalin. Does it mean both the Stalin statues have been moved there. And do you have the address of Mehmet Shehu’s house? I don’t think I’ve ever been there. If you give me the adress I’ll update the post in case anyone wants to go looking for them now that the art gallery may not return to what it was if any renovation actually takes place.

If you walk down rr Ismail Qemali from the Boulevard, into the former Blok, you walk along the north side of a little park. When you get to the end of the park, the house on your left is Mehmet Shehu’s house, so the address is probably the corner of Ismail Qemali and rr Ibrahim Rugova. The front or Enver Hoxha’s house is diagonally across the crossroads in front of you and at the back of the Shehu’s house, but whether there is a tunnel connecting them, as Kadare wrote, is not known. The house is used as a government guest house, and is under security guard, which prevents getting near. In the front garden you can see (the top parts of) Lenin and Stalin (and a jeep-like truck). I am afraid I cannot say whether there is any more, though someone suggested that some works from the gallery of Figurative Arts were being stored there on the inside.

Thanks for the update Adrian. I’ll try to work out how best to include the latest information in the other blogs where I’ve mentioned the statues of Lenin and Stalin. It will also be interesting to see how, or indeed if, they find a permenant home – accessible to the public – in the future of all the statues that were hidden away at the back of the National Art Gallery. I’m particularly concerned with the fate of the statue of Liri Gero