St George’s Hall – Minton Tile Floor – Liverpool

St George’s Hall is one of the most impressive buildings in Liverpool (in a city which has many) and gives an indication of the wealth that once passed through what was once claimed to be ‘the second city of the Empire’ – after London (although other cities claim this ‘accolade’, Glasgow and Bristol being two of them). The Minton Tile floor is an expression of this wealth.

I don’t want to go into too much detail about the building itself (I’ll do that in other posts) as here I want to concentrate upon the Minton tiled floor of the main concert room, which has recently been on public view for a couple of weeks. It wasn’t long after the building opened in 1854 that a decision was made to cover the sunken part of the floor to protect the tiles for posterity. In some ways a strange decision as the covering of the more than 30,000 tiles takes away much of the splendour of the hall itself. Don’t get me wrong, the concert hall is still very impressive, but it’s a bit like a book with part of the story missing.

However, that decision made so long ago does mean that on the occasions when the floor is uncovered visitors get an unparalleled idea of what was it was possible to achieve during the heyday of Britain’s industrial greatness. Comparing the protected tiles with the surrounds you are able to appreciate the way that the lack of protection has taken its toll in some places but also to realise that these tiles are incredibly hardy as many areas have survived quite well.

So a few facts and figures. St George’s Hall, built in the middle of the 19th century, is classified as a neoclassical building. That means it takes its architectural influence from the buildings that remain from ancient Greece and Rome – and the Hall mixes the two. Not strictly so, but more or less Greek on the outside and Roman on the inside, especially in the main concert hall where the inspiration for the architect, Harvey Londsdale Elmes, came from the Baths of Caracalla in Rome.

At the time when it was unveiled the floor was the largest pavement of its kind in existence being some 140 feet long and 72 wide and was constructed using more than 30,000 tiles. The part of the floor that is normally covered is sunken and is a couple or feet or so below the walk way that goes around the edge of the hall. When uncovered it’s possible to see the grills that were all part of the central heating (and cooling) system that was all part of the original design and one of the first of its kind in the modern world – we have forgotten much of what the Romans had learnt. However, the covering of the floor meant that the imaginative innovation came to nought, at least in the main hall.

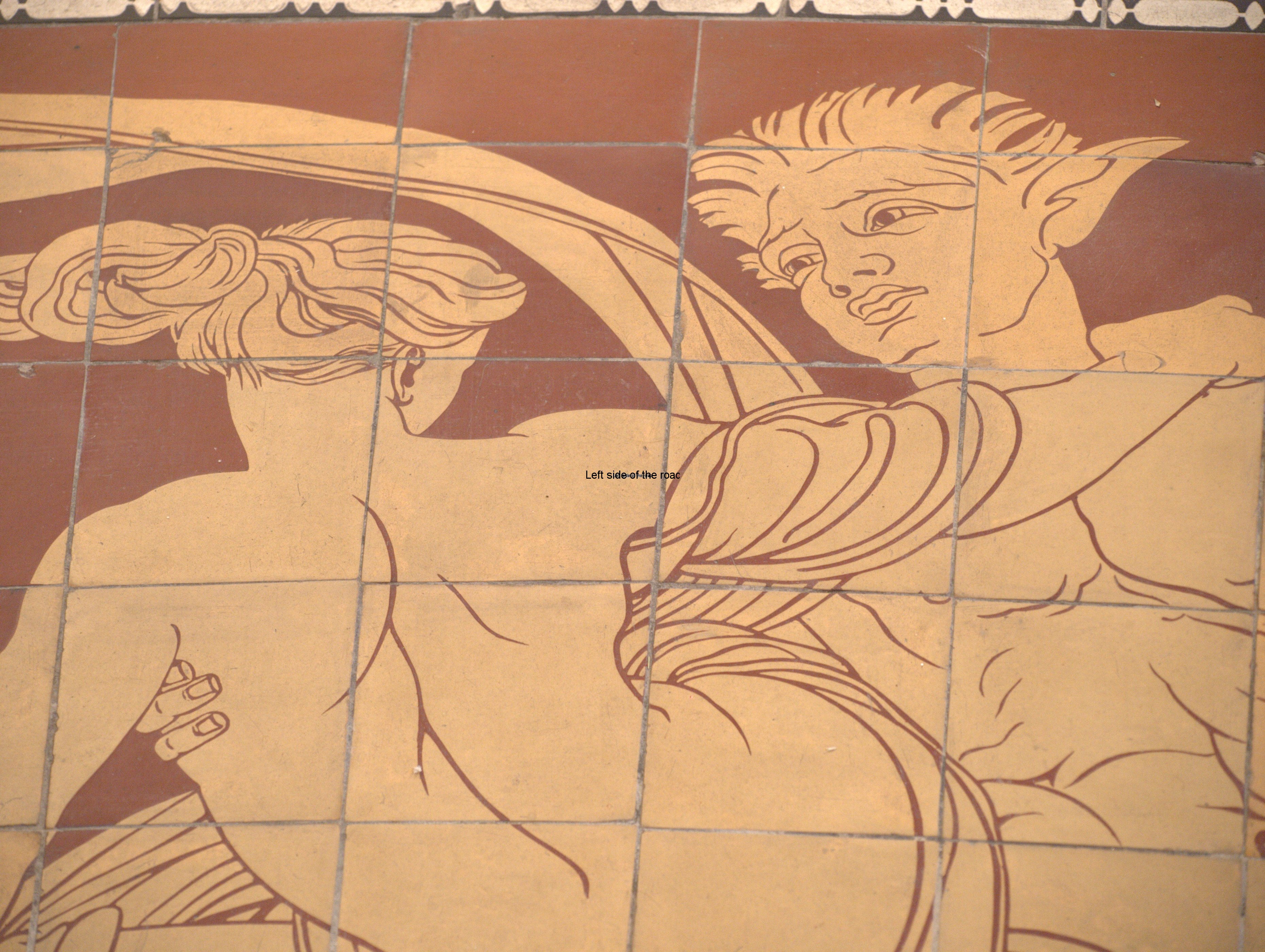

In the centre there’s the Royal Coat of Arms, measuring 5 feet in diameter. On both sides of that design the rest of the floor is basically symmetrical, along the length of the hall. Within those two areas are found: the Liverpool Coat of Arms; the Star of St George; the Rose; the Thistle; and the Shamrock. I’m afraid for the Welsh there is nothing, even though the Welsh had a huge influence on the early development of Liverpool and it’s more than likely that many of the men working on the site would have been Welsh, the building trades being where they tended to gravitate. Between these picture designs there are large swirling arcs which are made up of flower designs and filling the gaps geometric designs following a regular patter. At both ends of the hall there are semi-circles that have the face of Neptune at the apex and on both sides are sea satires and nymphs in amorous embrace, together with dolphins and other sea creatures. The dominant colours are buff, brown and blue.

To give an idea of how the tiles were made I can do no better than reproduce a description from one of the local Liverpool newspapers which carried a long story about the Hall at the time of its opening in 1854:

The antique practise of tile making, as appears from the existing remains of ancient works, confined the manufacture of the use of few colours or tints. The method commonly used seems to have been this: – A piece of well tampered clay having been prepared, of a proper size (usually about six inches square and one inch in thickness), a die, having some ornament in relievo was pressed upon it, the indented pattern thus produced was then filled in with clay of some other colour, generally white, the tile was then covered with a metallic glaze, which imparted to the ground (usually red) a deeper and richer colour, and gave the white ornament a yellowish hue. These tiles were often arranged in sets of 4, 16, or more, and sometimes intersected with bands of plain tiles, of a self colour, such as black, red and white, and frequently displayed great geometrical skill and beauty of effect. Good examples may be seen in the churches of St Denis and St Omer, in France, and specimens from the abbeys of Juvaulux, Westminster, and other buildings in England. The modern process of encaustic tile making, as adopted by Messers MINTON, HOLLINS and Co, enables them to produce not only a far greater variety and brilliance of colour in the general effect of a pavement, but admits of several colours being placed upon a single tile, thus producing a soft effect of fine mosaic work, in a much more durable and less expensive material.

From The Liverpool Mercury, September 19th, 1854

In the more distant past the floor was only uncovered at very long intervals, 10 years or more, but it looks like this event has set to become an annual affair.

There have been suggestions to try and construct a glass floor over at least a part of the sunken area but so far they have come to nought. And anyway that might allow an understanding of the skill of the craftsmen and the beauty of the design but not of its scale, which can only be appreciated when fully uncovered. To keep the floor on permanent display would bring into conflict the preservation of a unique architectural attribute with the desire to use a major City Centre public indoor space.

I hope the slide show below will provide an idea of what is hidden from view 48 weeks of the year.

Minton Tile Floor Reveal 2019

This year the floor will be uncovered between Thursday 1st and Monday 26th August 2019. Entrance is via the Heritage Centre on St John’s Lane from 10.00 – 17.00 everyday (but not Monday 19th August). Entrance to the Great Hall is £3.30 (under 16s normally get in free – but no information on webpage this year). This allows the visitor to get an overall view of the floor from the balcony.

There are opportunities to walk on the floor, obviously providing a closer view of the art work, as part of a guided tour. These will take place between 10.00-11.00 and 16.00-17.00 each day the floor is uncovered. In the past the demand has been so great that extra slots have been created – so check back of the ticket site for an updates if tours start to fill. Each group is limited to a maximum of 30 people. Only bookable online by visiting the TicketQuarter website. Tickets cost £13.20 per person.

There’s another option to get a closer look at the floor if you book for the event known as ‘A Night on the Tiles’ which takes place on Thursdays, Fridays and Saturdays between Thursday 1st August and Saturday 24th August from 18.00 and 21.00. This allows you to walk on the floor, you get a class of something fizzy and costs £15.40 per person. Get all tickets in advance, online, at the TicketQuarter page.

Update March 2021

The ‘reveal’ has become an, at least, annual event but this has been thrown into chaos with the pandemic. However, it will be safe to assume that once restrictions the pattern of opening will be resumed. Once details are known (perhaps towards the end of 2021) the updated information will be posted here.