Palau de la Música Orfeó Català – Barcelona

If you have any interest at all in Modernisme (the Catalan name for what is called Art Nouveau in Britain) then any visit to Barcelona has to take in the unique Palau de la Música Orfeó Català at the Via Laietana end of the narrow Sant Pere Més Alt. The work of the Barcelonan Moderniste architect, Lluís Domènech i Montaner (whose other great monument to Modernism is the Hospital de la Santa Creu i Sant Pau) this one building encapsulates all the aspects which arose time and again in the short 20-30 year period of Moderniste dominance which straddled the 19th and 20th centuries. Love it or hate it you can’t ignore it!

Here I don’t intend to give a history of the building, facts and figures and all the rest. Others have done that before with more authority and knowledge and all I would be doing is paraphrasing what they’d already written. Here I want to address a few matters that came to me after my visit in February 2014.

If Modernisme was to have a revival in Barcelona in the 21st century it could never take off in the same way that it did in the 1880s. Most of the skills that were used in the buildings that litter the Eixample district (and which appear in other locations in the city and Catalonia in general) have been lost in the intervening years and bringing together craftsmen with such a variety of skills would be a Herculean task in itself.

The lack of skills is one thing, the lack of materials is another. All the materials that were used in buildings such as the Palau de la Música were sourced and manufacture locally. At the end of the 19th century Barcelona had become a centre for ceramics and provided the Moderniste architects an inexhaustible supply of materials for the trancadís (which means broken) style of using tiles on curved surfaces so beloved by Gaudí – as is seen in Park Güell – and by Domènech i Montaner’s construction for the Orfeó Català.

The other materials used extensively included wrought iron, bricks and coloured glass all again major industries in Barcelona and the surrounding areas at the turn of the 19th/20th centuries. The de-industrialisation that Barcelona (as have so many other European cities) has undergone in the last 30 years or so means that all such material would have to be brought in from abroad, most likely from China. And China is now probably the only country in the world which could produce such buildings and I wouldn’t be surprised to read that some opportunistic capitalist in the once great Socialist country is planning to open a Moderniste theme park.

When I had the opportunity to go inside the Palau de la Música in the late 90s there were only something like one or two chances a week. If you didn’t book well in advance there was little chance of getting in. I also think, but can’t be sure, that the numbers in those groups were relatively small. Now there are tours on the hour and they take up to 60 people at a go. At €18 a go that adds up to a lot of money.

One of the consequences of this huge rise in visitors is a dumbing down of some of the history of the building. When it was started in 1905 Catalan nationalism was big and as well as the influences from nature, the moving away from the man-made straight line with a greater use of curves and the depictions of women as an integral part of the designs this nationalism became a fourth strand in the Moderniste architects armoury.

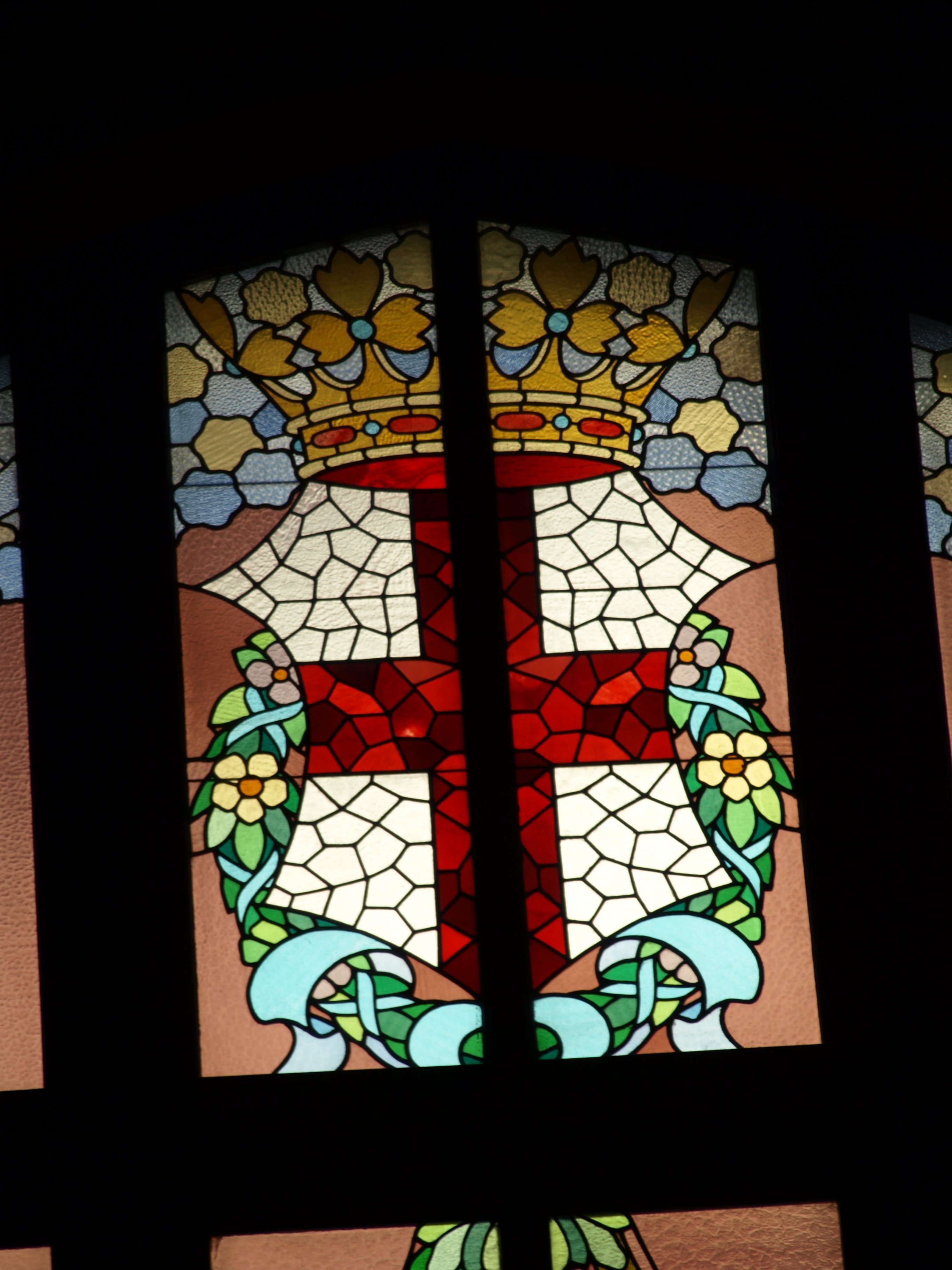

This meant the repeated representation of the Catalan flag, the yellow and red, and the red cross on white, symbolising St Jordi (St George) especially in glass but also in ceramics. The shield of the Catalan lines also appears carved into both wood and stone. But come the victory of the Fascists under Franco in 1939 this all became a no no.

Franco was for a ‘united’ Spain at any cost and imagery that contradicted that ideology was removed from view. That meant that the Catalan flag that appears on the top half of the windows on all three levels of the main concert hall were blanked out. Why they weren’t just destroyed and removed forever I don’t know. Presumably the Fascist in charge had an uncharacteristic sense of culture. This was mentioned as part of the tour some years ago but is not considered to be of relevance now, or so it seems.

This de-politicisation of the past, more significantly the period between 1939 and Franco’s death in 1975, is something which none of the regions of Spain that I’ve had the opportunity to get to know seem prepared to face. Just ignore it and it will go away, seems to be the hope. But that won’t happen when parties like the PP (Partido Popular, a mish-mash of proto-Fascists and head banger Opus Dei Catholics) are around and even in power at a national level at the moment.

On a completely different tack, and something which I can’t remember occurring to me in the 90s, is how Domènech i Montaner was able to design a structure which uses so much hard material (such as marble, ceramic tiles and glass, as well as a not insignificant amount of wrought iron) was able to produce a concert hall that has been used for solo singers to full-blown orchestras and no one complains about the acoustics.

I’ve never attended a concert in the building (which must be difficult for those who either love or hate the design – one group would be forever looking around in admiration and the other with their eyes closed) but just experiencing the voice of a female guide, talking quite normally in a large space, I had no impression that sound quality was an issue.

This I find difficult to understand. Most concert halls I’ve been to seem to be buried in the deepest heart of the building away from any outside influence but here the main concert hall, on three sides, has the outside world just the other side of the glass windows. (OK they are now ‘double glazed’ but that’s not making much of a difference from the original arrangement.) It even gets lit in the day time by the light provided by the sun.

If I compare this place with the Liverpool Philharmonic Hall, for example, they are so completely different. In the Liverpool Phil there’s nothing harder than the brass instruments (if you ignore the heads of some of the patrons) to interfere with the acoustics – soft wood and highly technological design of the padding is the order of the day there. All missing from the Palau de la Música Orfeó Català, which has been around for considerably longer.

Finally, everything must change, nothing stays the same, but why is it that so much change is for the worse?

Although I’ve been to Barcelona over the last few years (there was a gap in the early 21st century when I wasn’t in Catalonia at all) for different reasons I hadn’t been around the Sant Pere district, where the Palau de la Música is located. So it was with an element of shock that I returned to find that someone, in their infinite wisdom, had decided on a modern extension to the building on its western side, the one facing Via Laietana.

I might have known, but hadn’t remembered if I did, that the building had been given a World Heritage Building status in 1998. I can go with that. It’s unique and seems to deserve that level of recognition as a form of protection – but that hasn’t been the case.

I fail to understand what ‘World Heritage’ status really means.

I’m not, I believe, against modern architecture. In fact just the opposite, it’s just that where I live we seem to get the worst of the results. If ‘planning’, as we’ve got to know it in the 20th century and subsequently (even though the Tory philistines are seeking to claw back what little we’ve gained in the UK), means there are restrictions on what and where developers can build this should be supported by international bodies.

If cities and, in the case of the Palau de la Música, buildings are going to boast about and promote the fact of their World Heritage Status (it’s even on the entrance ticket) then the awarding body has to take some action if, after the designation of such an accolade, the city/building then goes and does something which, for any normal, thinking and concerned individual, seems to go against the principles of the award in the first place.

For example: the building of three totally inappropriate buildings on Mann Island, between the Albert Dock and the Pierhead in Liverpool.

For example: the building of a huge (though almost certainly impressive technologically) road bridge over a valley close to Dresden, Germany, and destroying the classic view of the city, known as the Waldschlösschenbrücke.

For example: the building of a high-tech extension to the Palau de la Música.

When I first saw the building I’m sure I came from the direction of Via Laietana. That’s how most people arrive. When it was planned,and then built, in the first years of the 20th century it was on a limited space, a church being on the west and apartment buildings already on the north, east and south. Some years ago the church was knocked down which opened up a square so that by turning the corner from the main road you would, all of a sudden, be confronted by this wonder/monstrosity – depending upon your attitude.

Now that’s all gone.

The western façade is hidden behind a glass walkway and the part directly joined to the main entrance of the original building has been totally obliterated. So what at one time was an opening up of the view of the building has been lost behind modern concrete, glass and brick.

The rounded brick corner that follows the line of the main entrance is a clever piece of brick work and design, but it’s in the wrong place. On the corner there’s a representation of a tree and if it had been anywhere else I would have had nothing but praise for the architect/designer. As it is this structure houses a smaller concert hall – if one was really necessary in the centre of Barcelona did it need to be there? – and, I’m sure, of more importance to the owners/managers of the space, a fancy corporate entertainment space. The day that I was there was the day before the opening of some the Mobile World Congress conference/jamboree/blowout/extravaganza.

Now in all these cases the owners/managers/politicians would have said that this was vital for the economy of the building/enterprise/economy/employment/etc./etc. I’m not from Barcelona but I’m not aware that all this wealth has ‘trickled down’ to those who are facing dire consequences due to the bankers/politicians created ‘crisis’. (How can it be a ‘crisis’ if the rich continue to get richer and the poor get poorer?)

But my final comment/question is: Why does World Heritage continue to go against its stated aims? If the organisation doesn’t care about these places and puts the dollar/pound/euro before any historical or cultural considerations then at least be honest and say so. Don’t maintain the moral high ground and then fall at the first hurdle.

Next we will read that Coca Cola has put a flashing neon/LED sign on top of the Taj Majal and McDonalds are serving their special, unique and nourishing creations to visitors as they behold this monument to love and devotion.

And no one will care a toss.

Practical Information:

Location: From Via Laietana the Palau is at the beginning of the narrow Sant Pere Més Alt. The ticket office is in the new part of the building, at the opposite end to the main entrance, and after the corporate entertainment section – few of you will be invited there.

Getting there: From Metro L4 (the yellow line) on the Via Laietana exit it’s only a few metres from the beginning of Sant Pere Mès Alt,

Entrance:

There are two types of tour, with a physical guide or self guided. For either it is probably best to book online – although you can also book at the ticket office attached to the building.

Price: Online €11 + €1 booking fee, children under 10 Free

Price: Online €10 + €1 booking fee, children under 10 Free

The tour is offered in the following languages: Catalan, Spanish, English, French and Russian – check the screen beside the ticket office for the times when your choice of language is being offered. The guided tour is about an hour long, entering and leaving at the same place, the original main entrance in Sant Pere Mès Alt.