Xcalumkin – Campeche

Location

The pre-Hispanic settlement occupied a large savannah of kankab or reddish earth, measuring approximately 5 km along its north-south axis and 2 or 3 km wide, and surrounded by hills that are nowadays used for irrigation and/or seasonal farming. In the core area of the site are two cenotes or natural wells, which may have given rise to the human settlement. In any case, the Maya complemented these sources of water by building underground cisterns or chultunes near their dwellings. The name of the site is derived from the Yucatec Maya and may be a reference to a ‘very fertile spot well lit by the sun’, which is characteristic of the savannah. Xcalumkin is situated 85 km north-east of Campeche City. After reaching Hecelchakan, take the road to Cumpich and after 12 km turn off on to the dirt track leading south to the archaeological area.

History of the explorations

Teobert Maler was the first person to report the site, in the late 19th century. He took photographs and recorded the architecture still standing. During the first half of the 20th century the carefully cut veneer stones covering several of the buildings were heavily plundered and sculptures and hieroglyphic inscriptions were acquired by collectors. The ruins of the Maya city were then visited sporadically by experts such as Alberto Ruz, Paul Gendrop and George Andrews. However, they were studied in greater detail in the 1990s by a team of French archaeologists from the Museum of Mankind in Paris, led by Pierre Becquelin and Dominique Michelet. They drew up the first map of the site and a detailed record of the surface architecture. Around the same time, Antonio Benavides C. embarked on the first consolidation works. He has been joined in subsequent campaigns by Heber Ojeda and Vicente Suarez from the Campeche branch of the INAH.

Timeline, site description and monuments

The architecture and ceramics indicate a timeline of occupation commencing in AD 500 and ending in 900. The settlement is large and only a few buildings in the core area have been restored. The more distant groups are still covered by vegetation.

Building on the north-west hill.

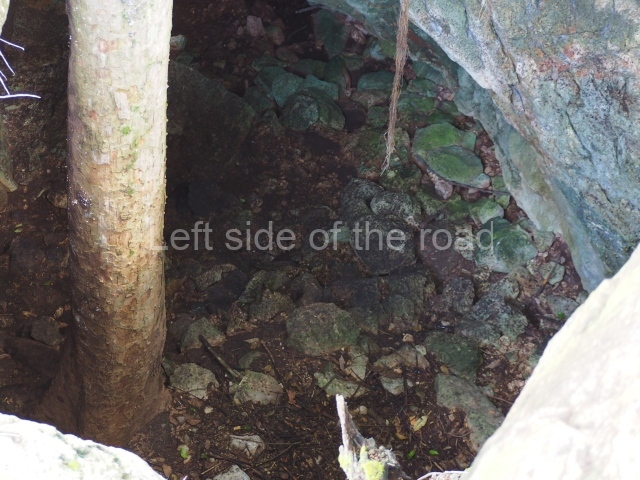

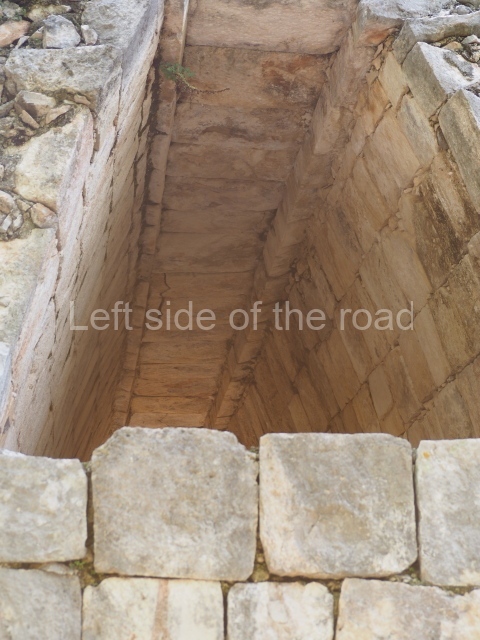

The first building that can be visited is situated at the top of a natural elevation some 15 m above ground level and consists of three south-facing rooms; the central one is connected to another interior space and its facade is partly covered by a projecting stairway leading to the roof or top floor. The northern section bounds a plaza at the top of the hill, at the centre of which the Maya built a cistern. Here, a new concrete ring protects the mouth of the chultun and prevents accidents. Originally, there was a carved stone ring with four perforations to channel the water.

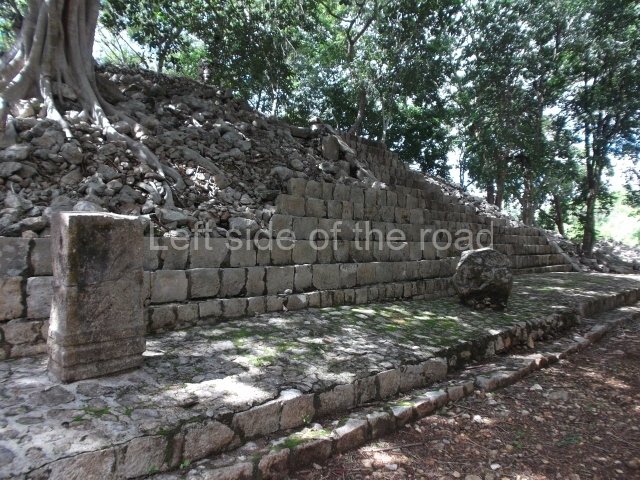

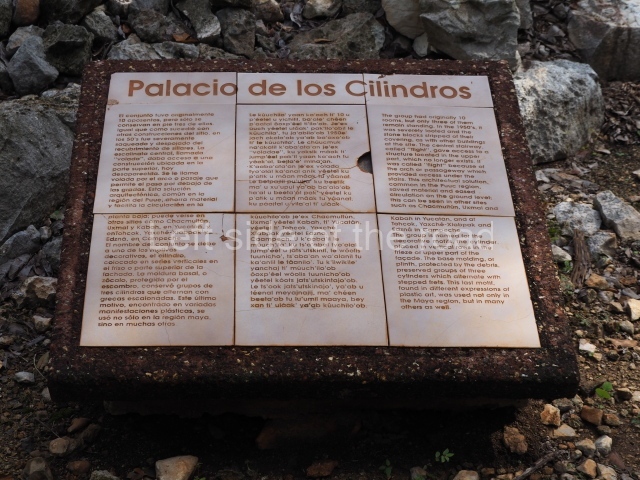

Palace of the Colonnettes.

This monumental building once contained ten rooms, each with their own entrance. The name of the palace is conventional and suggests that it was the residence of the Xcalumkm rulers. It stands on a large rectangular platform and its south facade has a stairway leading to the second level. At the top and bottom of the stairway, the corners are decorated with three smooth colonnettes crowned by a triple moulding. The impression is of small constructions that summarise the Classic Puuc architecture. In front of the building and the platform stands a monolithic column of a later date. It probably formed part of another monumental construction, but during the Postclassic it must have been used either as an altar or a place for depositing offerings. Behind the stairway a vaulted passage facilitates the circulation between the rooms on this side. The building takes its name from the long colonnettes that decorate the frieze or upper section of the wall. Due to various episodes of plundering, only three of the original rooms are still standing today. The one on the west side contains a stone sculpture that was rescued near the site. It represents a seated aged female (xnuk, in Yucatec Maya), a mythical figure that appears in the legends of rural communities and who is said to grant special favours in exchange for children or human lives.

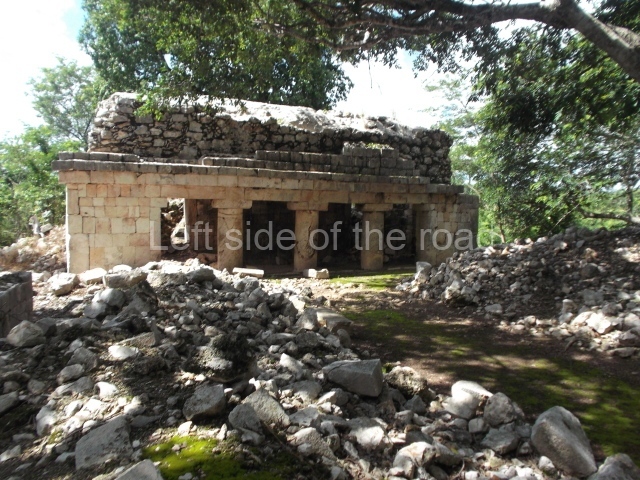

Courtyard of the Columns.

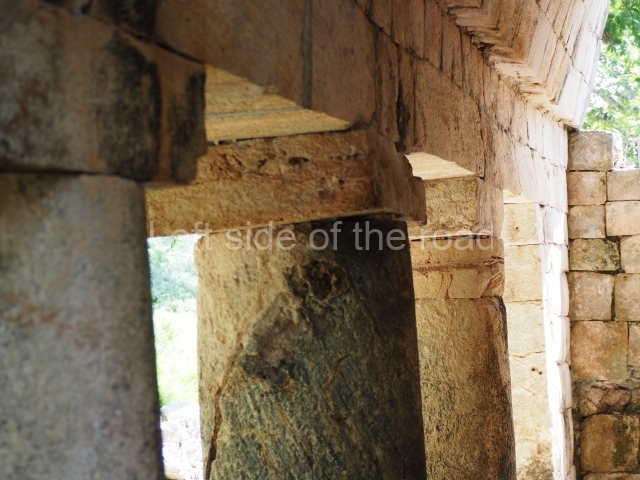

Just south-east of the Palace are two courtyards. The north side of this one is bounded by early buildings that contained rooms with numerous entrances formed by columns, while the east, south and west sides display constructions with several entrances. In the south-west section of the courtyard a ramp leads south to the adjacent courtyard.

Courtyard of the Altars.

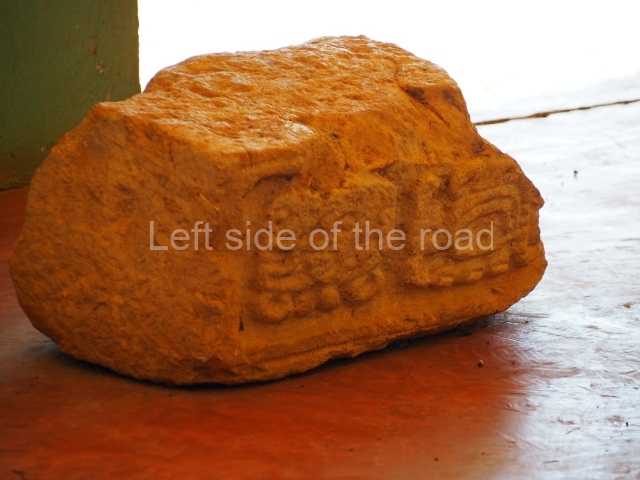

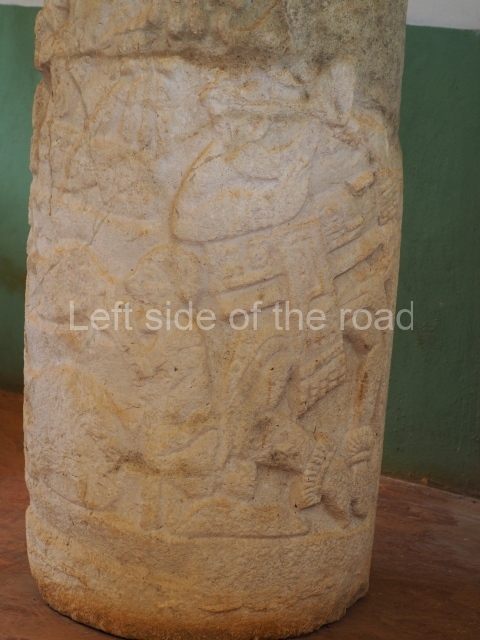

This is accessed via the north-west corner, coming from the previous courtyard. In the middle stands a large but low platform, quadrangular in shape, which had small stairways on two sides. Just south of the platform, two stairways lead to two separate temples built on older constructions from the Early Puuc phase. These have several entrances formed by columns, which now serve to support the temples. The stairway in the south-west section has balustrades and the temple at the top was accessed by a tripartite entrance formed by columns with several drums. Inside, it is still possible to see a small rectangular altar in the middle of the space. In the south-east section are two altars at the foot of a stairway. One adopts the form of a rectangular limestone prism decorated with criss-crossed lines to indicate a woven mat, the pre-Hispanic symbol for political authority. The other altar was a large colonnette, also made of limestone, but due to erosion and neglect it now looks like a large sphere.

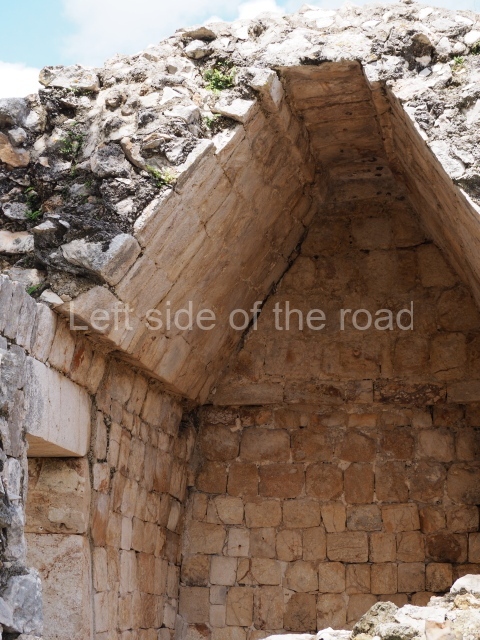

Initial series group.

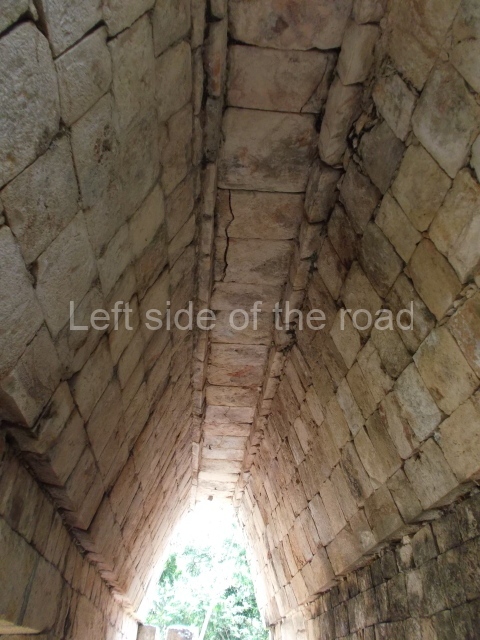

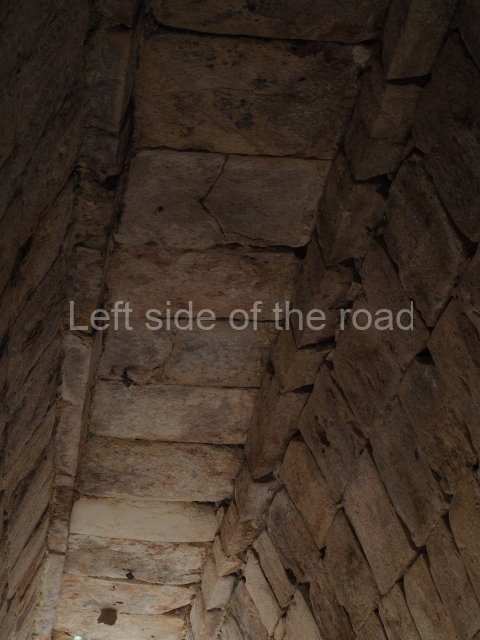

Situated south of the previous space, this is composed of a platform 3 m high on which four monumental buildings were erected, although nowadays only the north and south ones are still standing. The south building has four entrances formed by three columns. Its facade displays carefully cut blocks of limestone which were once decorated with a variety of painted stucco motifs. Inside, it has an elegant and very high corbel-vault ceiling made out of blocks specially cut to fit specific points. The group takes its name from the north building because this construction once boasted a long hieroglyphic inscription containing an ‘initial series’, that is, the appropriate information to match the Maya date with our calendar. The Maya date in question is ‘9.15.12.6.9. 7 Muluc 1 or 2 Kan kin’, which is equivalent to 27 October AD 743. Unfortunately, the inscription was stolen and nowadays graces a private collection in Mexico City. The central section of the rear wall of the north building is recessed, this being the place where the hieroglyphic inscription was found.

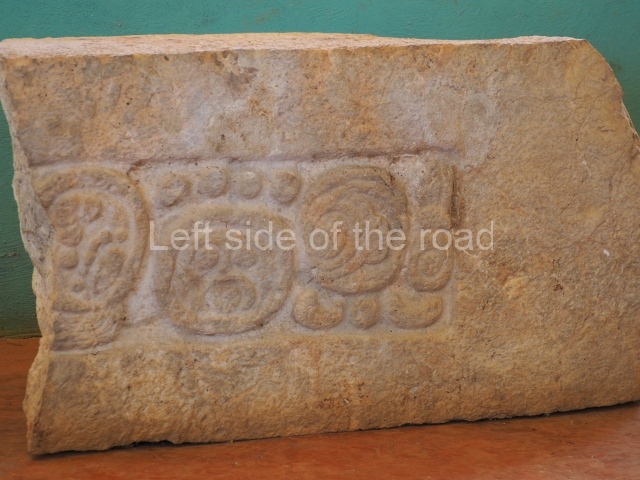

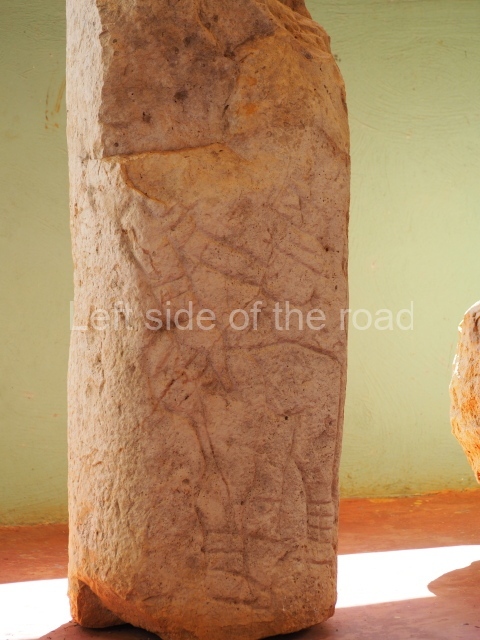

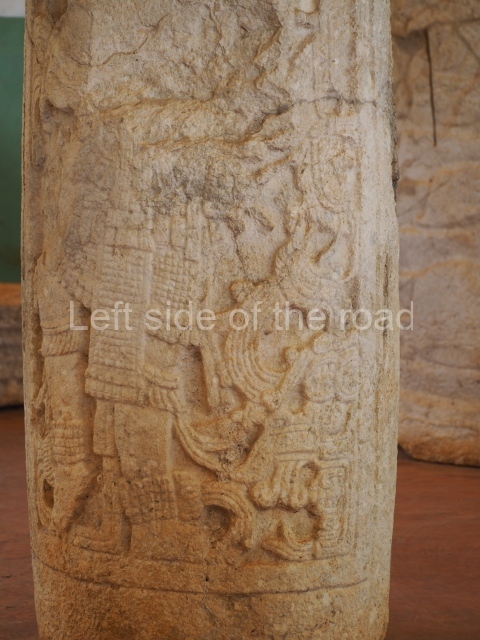

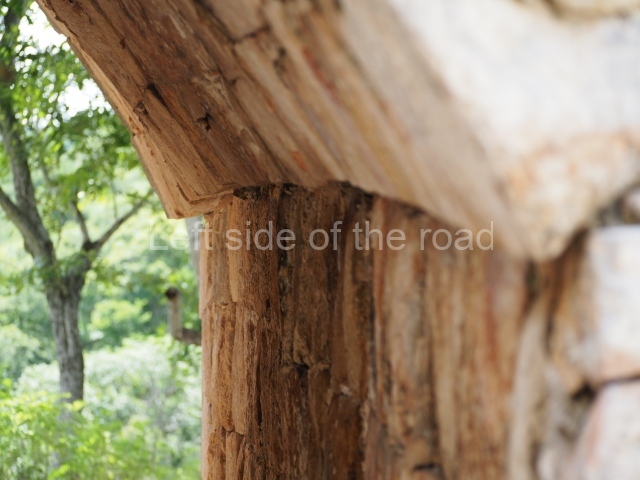

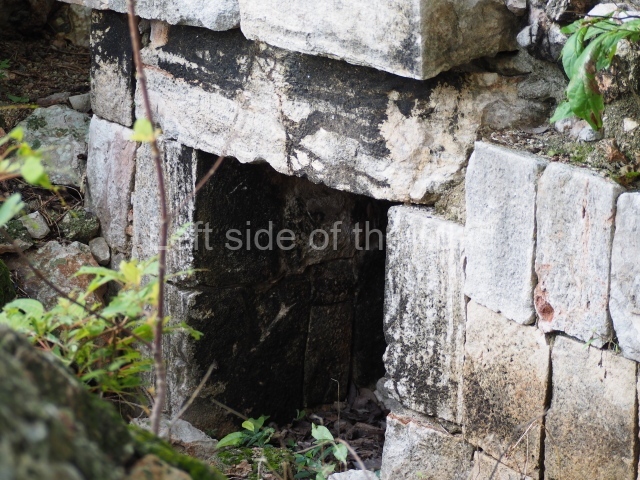

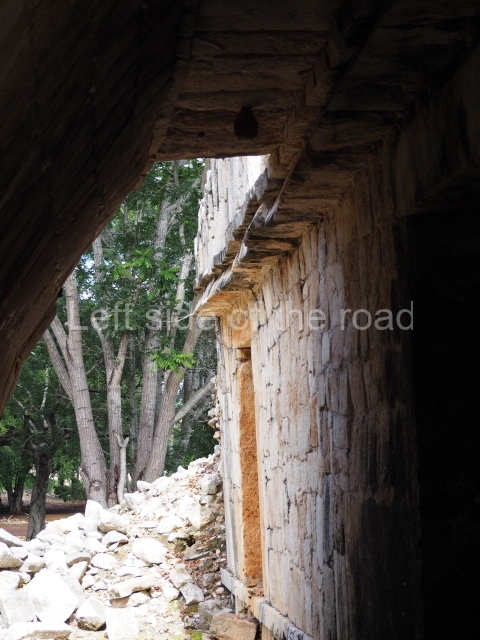

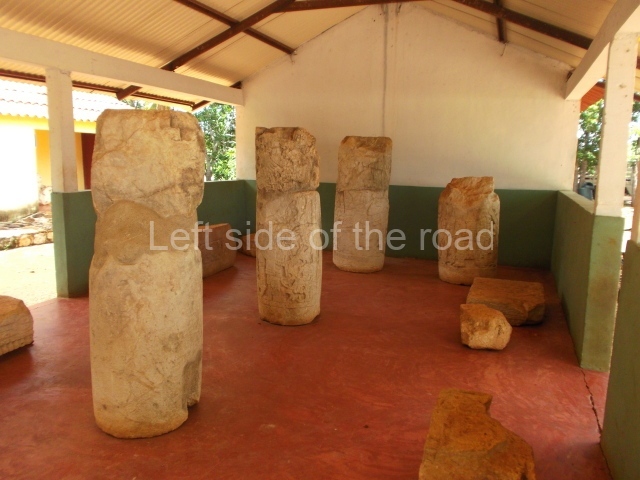

House of the Great Lintel

This is situated in the south-eastern section of the site and was thus named because of the size of the lintel above the main entrance. It once contained three rooms but only the central one is still standing. It was built between AD 700 and 800. Several pieces from Xcalumkin are on display at the Hecelchakan Museum and in various museums in Campeche City (the Baluarte de la Soledad tower and Fort Saint Michael). The most interesting items are the monolithic columns with large hieroglyphs. These formed the entrances of some of the palaces at the site. Other important items are the blocks of stone with glyphs culminating in serpents’ heads, which formed part of an impressive hieroglyphic doorway. There are also jambstones and panels depicting important pre-Hispanic dignitaries at the ancient site.

Importance and relations

Xcalumki’n maintained strong ties with its neighbours. With the closest ones, it shared the Xcombec Valley, east of Hecelchakan, where the palaces at many sites had multiple entrances formed by columns with carvings of figures. It also maintained relations with the coast, specifically with Jaina, whose emblem glyph has been identified at Xcalumkm. It was a contemporary of Uxmal and Kabah in the north-east, of Halal and Itzimte in the south-east, and of Kanki in the south-west. The numerous hieroglyphic inscriptions reported at Xcalumkm are also indicative of its former importance.

From: ‘The Maya: an architectural and landscape guide’, produced jointly by the Junta de Andulacia and the Universidad Autonoma de Mexico, 2010, pp 317-319

How to get there:

There is no public transport along the road between Hecelchakan and Bolenchen so the only way is probably to hire one of the purpose built (as opposed to the Heath Robinson constructions) tuk-tuk’s. You will need the best part of an hour at the site.

GPS:

20d 10’ 19” N

90d 00’ 36” W

Entrance:

Free