Alberto de Agostin – Puerto Natales

Indigenous representation in public art – the church

Whoever decided that the 500th anniversary of the ‘discovery’ of America should be commemorated on 12th October (previously known as ‘Columbus Day’) 1992 they must have been surprised by the reaction that followed the announcement. How could a piece of land, however huge, have been discovered by Europeans if there were already millions of people there who had developed a whole series of complex and successful societies which compared more than favourably to ‘Old World’ empires. The history of these civilisations in the Americas went back as far as those of which the Europeans were aware.

This wasn’t the first time this event as a celebration had been challenged but, especially in western Europe, the call for a celebration opened up the discussion that the arrival of Columbus and his small fleet of three trips in the Caribbean island of what he named San Salvador was, in reality, the beginning of one of the greatest genocides in world history.

Whether by accident (the indigenous population hadn’t encountered diseases common in Europe, such as influenza and smallpox, and therefore had no resistance and these diseases killed an untold number of people – however when the colonisers knew of this they used the first examples of ‘biological warfare’ well into the 19th century against the Plains Tribes of North America) and then through slavery and exploitation the indigenous population were virtually extinct – if we were to use the modern definition of extinction that is applied to flora and fauna throughout the world.

In Latin America countries there had been various names for the ‘celebration’ of the 12th October – too many, too diverse and too complicated for me to go into here (even if I understood all the local arguments) – but none of them really were concerned about the people who once populated the lands that were now in the hands of the descendants of the first European colonisers.

As was said about the missionaries and the colonisers in Africa (I thought there was a version of it for Latin America but I haven’t been able to find it yet) ‘when they came we had the land and they had the Bible, now we have the Bible and they have the land’ – attributed to Chinua Achebe in his novel ‘Things fall apart’ – so was the case in Latin America.

But after 1992 the governments in that continent thought they had to make some sort of concession to the past crimes. Not that they were going to give the land that had been stolen back to the ‘owners’, not that they were going to treat the descendants of the indigenous peoples in any way other than the one they had been following for the previous 500 years. No nothing like that.

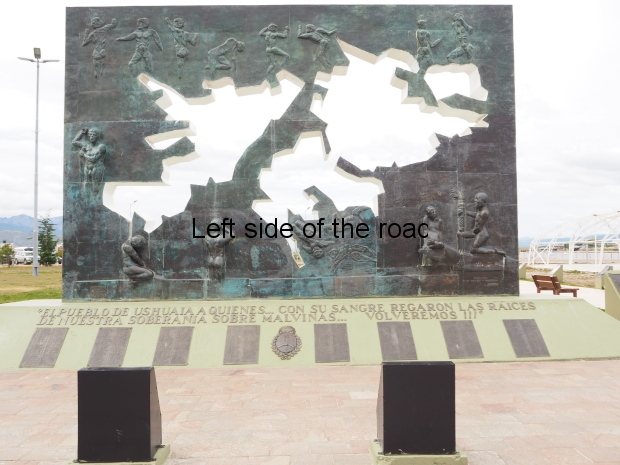

They would issue a mea culpa, they would erect statues and monuments and they would shed crocodile tears but the situation would not change for the indigenous peoples. They would still be the ‘untouchables’ of the American continent.

(As an example of this I can only refer to my previous posts, and experience in Argentina, on the demonstration on the occasion of the G-20 summit in Buenos Aires earlier this year as well as the demonstration I encountered a few days earlier.)

One of the consequences of this is that there have been a perfusion of monuments erected to the ‘indio’. But although these are supposed to turn the invasion of the country into an ‘encounter between two worlds’ (which seemed to be the compromised reached in Europe in the 1990s) I think the images that have been, and still are being produced in Argentina only serve to perpetuate the old way of thinking.

‘New wine in old bottles’ might be a way to describe this approach. A more aggressive way would be to say that the racism is so ingrained that even when the intention is supposed to be good the result is not.

I intend in this post to describe some of the images I have seen in my relatively short visit to the Argentina – with a short diversion to Chile due to geography and the drawing of borders – giving my interpretation of those images. Instead of waiting until the end of my trip I will post what I have already seen and add any more that I encounter in the future, together with changing my approach if something catches my attention which indicates a different point of view.

The Catholic Church

I might as well start with the biggest bunch of hypocrites, thieves and perverts who have been involved in so much that has caused suffering to the indigenous population to millions in Latin America – yet so many of the victims will still consider themselves part of the faithful. (When looking at the fate of the indigenous population in Latin America it’s perhaps important to remember that they are also part of their own problem.

(As an indication of this I’ve never seen images of Christ on the cross, made by local indigenous artists in any Latin American country I have visited, which display so much pain and suffering. The images in Spain and Italy are mild by comparison.)

The incumbents in the Vatican might have taken a slightly different view in public but substantially the situation has remained the same – just take a look at the politics of contraception and abortion.

I was in Peru a few years after Karol Wajtyla had visited the city of Cusco in the late 1985. In preparation of the visit a large white cross was erected in the area around Sacsayhuaman (the pre-Colombian ‘fort’ above the city) and which could be clearly seen from the city. Local people considered the erection of this cross (which I assume is still there more than 28 years later) as a dagger into the heart of the indigenous people. The cross is planted in Inca territory and looks down on the Inca capital. Not much of an apology there.

But Wajtyla was the most recent fascist wearer of the Triple Crown so nothing other could be expected from him. But such an imperialist attitude has, is and will pervade the Catholic Church as long as it exists. How can it be otherwise? If there is only one God how can the church (Catholic or otherwise – the Protestants weren’t slow in coming forward to destroy indigenous religions) accept societies who have a myriad of religious entities? Such ideologies cannot live side by side. In the 16th century in Peru this eradication of the heathen was known as the ‘extirpation of ideology’. I don’t see any reason to believe that this approach has changed in any way.

So to how the indigenous people are represented in Argentinian and Chilean churches.

Cathedral – Rio Gallegos, Argentina

First, a bit of background. Giovanni Bosco was a 19th century Italian priest. He established the Salesian Society and it was these missionaries who were sent to Argentina and Chile in 1975. It’s for that reason his image is in virtually all Catholic churches and cathedrals in Patagonia, if not in other parts of Argentina.

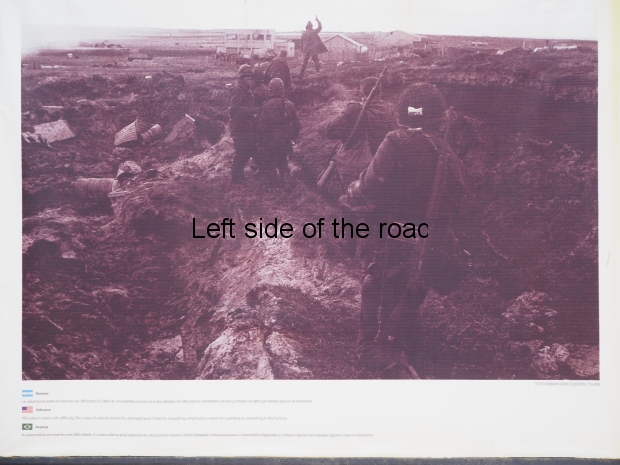

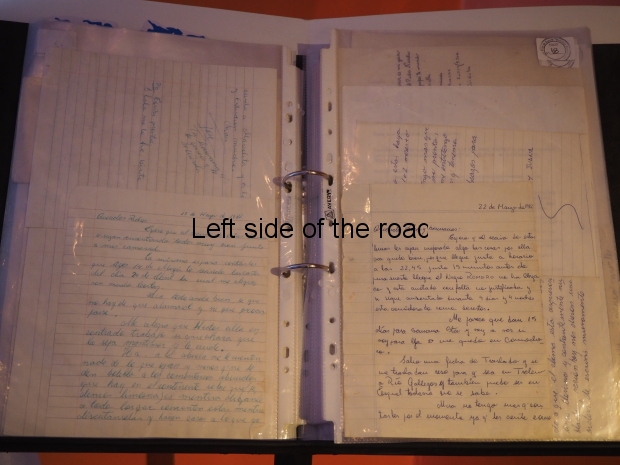

Rio Gallegos Museum

In this small cathedral (must be one of the smallest in the world) is a statue of Bosco and two young boys. The one of European extraction is standing, is dressed like a little bourgeois, together with a bow tie, and is wearing shiny, black shoes. He has a book under his arm together with a bunch of flowers and is looking up admiringly at the face of Bosco who returns the favour by placing his left hand on the boy’s left shoulder. In his right hand the boy holds a scroll with the words ‘La muerte mas no pecar’ – ‘Death but not sin’ (I don’t really understand that.)

The indigenous boy, on the other hand, couldn’t be represented in a more different way. He is naked apart from an animal skin that is over his left should but his right is bare. His hair is long (the bourgeois’s is trimmed short and tidy) and he has a ‘heathen’ golden band around his head. He is kneeling on the ground and is bare footed. He holds the base of a wooden cross in his right hand and his left hand supports the cross piece. His left cheek is pressed against the cross and he is in the process of going to kiss the cross. He is ignored by the other two characters in the tableau.

He doesn’t even get to have the Bible, all he gets is a bit of old wood.

Cathedral – Punta Arenas, Chile

In this cathedral, in the first chapel on the left as you walk through the main entrance, are two stained glass windows that depict the indigenous people from the local area.

Punta Arenas Cathedral

The first is of a male figure, with a large animal fur draped around and otherwise naked body, who is bare footed and carries in his hands a bow and arrow. At the bottom of the window is the name Rio Grande a town quite a distance away, even today, on the Atlantic coast of Tierra del Fuego. Above this large figure, which fills most of the window, is the image of a 19th century church building (presumably the main church of Rio Grande – but I never saw it) and in front of this church a priest, both his arms raised high above his head, with a crucifix in his right hand, is preaching to the (male) heathens who are sitting on the ground in a circle around him.

Punta Arenas Cathedral

In the same chapel is a companion window, this time of an indigenous woman with a baby on her back. She is also naked but for a large animal skin (do you start to see a pattern developing here?) and is likewise bare footed. I think we can assume the little child is also naked under the skin she shares with his/her mother. The woman is carrying a bag, presumably made from animal skin. below her feet is the name of Isla Dawson, a large island to the south of Punta Arenas.

Above her head this time we have a couple of nuns standing and around them are sitting, on the ground, a group of indigenous women. Out at sea is a large sailing vessel, the image representing modernity and civilisation which the Europeans had brought with them.

So increasingly in these images we are being shown the contrast between what was in Patagonia for many generations – with the low technology and ‘primitiveness’ – as opposed to the modern clothing and way of life that existed in mid-19th century Europe.

There’s another interesting image of the contrast between the two distinctive groups in the cupola over the main altar. I think it’s important to stress that idea of separateness. In none of the images is there any indication of the races mixing. One is of European extraction and is sophisticated the other has been in Patagonia longer but had never achieved anything like the same advances in technology.

Punta Arenas Cathedral

Here we maintain the separate education of the boys and the girls. As in the statue in Rio Gallegos the European boys and girls are in their bourgeois Sunday Best. But the area I would to discuss here is the group around the priest on the left.

Cathedral – Punta Arenas

This group is comprises six male figures. The priest in the most prominent position, a young adult and three boys – all in late 19th century dress. The five Europeans all have either a paper representing different aspects of religious teaching or have some contact with the written word – the priest has his right hand on a Bible. The idea of modernity is stressed with the inclusion in the classroom of a globe and various scientific instruments.

In the middle sits someone who is totally out of place – and as in the Rio Gallegos statue, he is there but not there. If any of the characters is relating to him in any way it is by bombarding him religious homilies and he looks totally bemused, seeming to say to himself, ‘What am I doing here?’.

As is the norm in such circumstances he is dressed in some animal skin, very much like a sheep’s fleece, but his nakedness, and hence is difference, is depicted here by the bare skin around his throat. His ‘heatheness’ is depicted by the necklace. He’s not on the ground this time but on a small stool but that’s the only level of elevation.

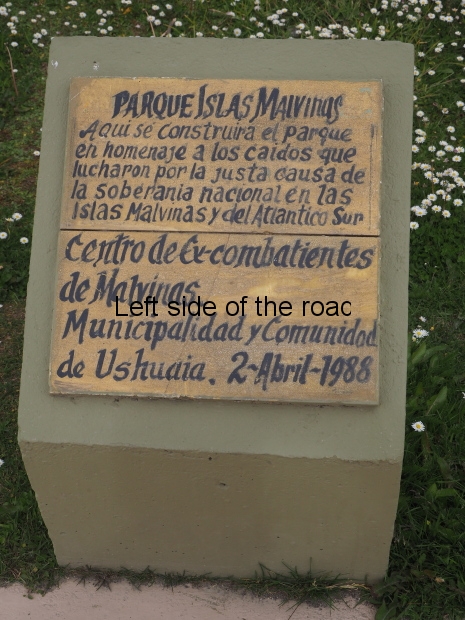

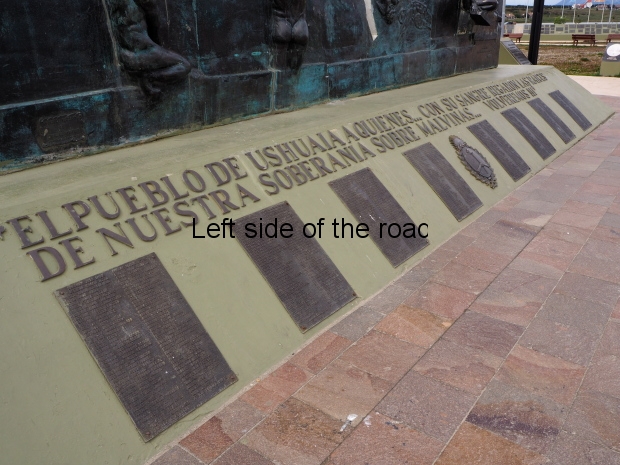

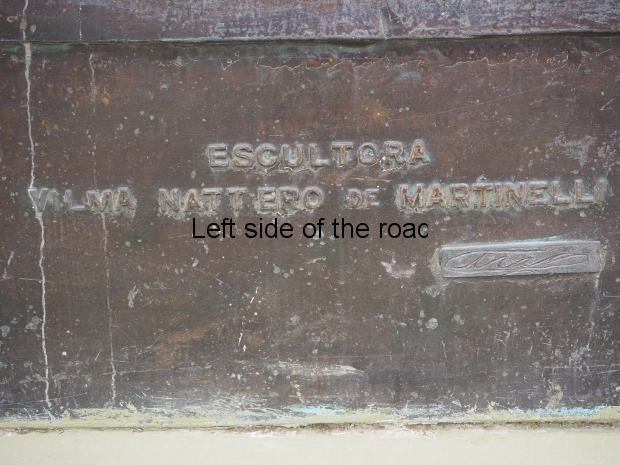

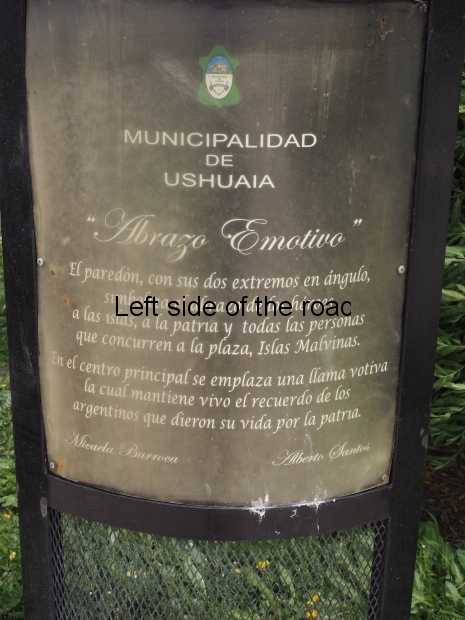

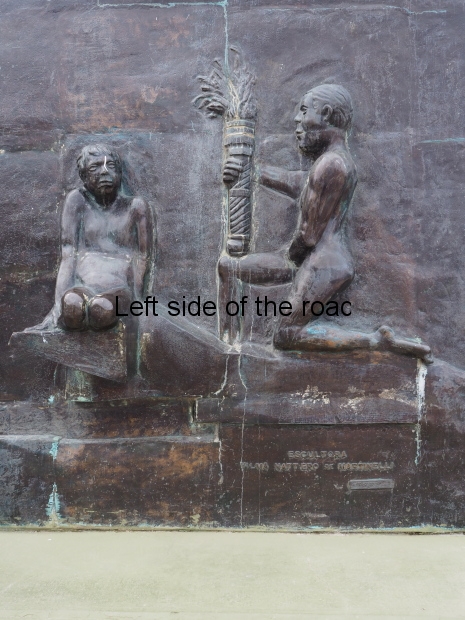

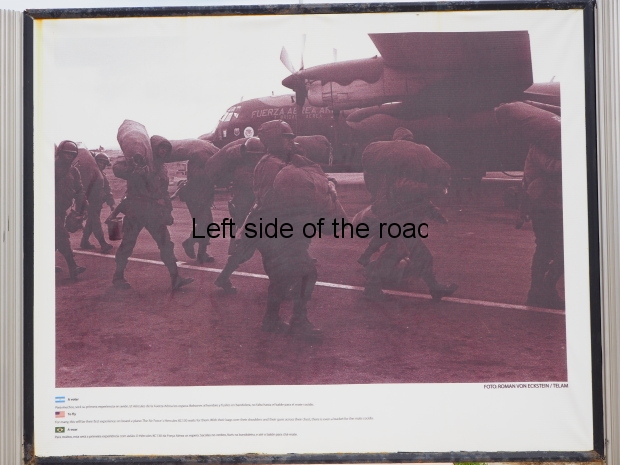

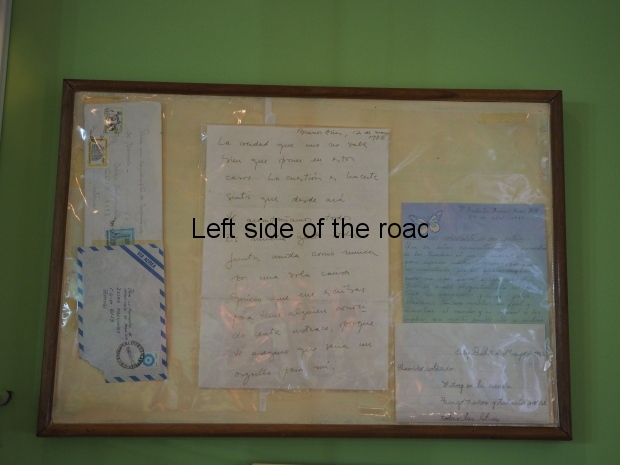

Cathedral – Puerto Natales – Chile

Cathedral – Puerto Natales

This again revolves around an image of Bosco. In any painting he will always be depicted in a prominent way, even if only his image is sharper and brighter. And it by this contrast that we see the representation of the indigenous people in the Cathedral of Puerto Natales.

These’s the difference in dress, as we’ve seen before, but here they are also pushed, literally, into the background. The group of three, one standing and two sitting, to the right of Bosco seem to be there merely to fill in the space. They play no role in the story (Bosco never came to Patagonia himself) and seem disinterested in the role they have been asked to play.

Cathedral – Puerto Natales

On the left of the painting, however, there’s a story we haven’t come across before. The young boy standing with the red smock is halfway from becoming civilised. He wears trousers and shoes but he is still not quite European as his smock emphasises. He is starting to become European, even with his haircut, but he has adopted the church as he is holding a large book in both his hands.

I’m not totally sure how to read the three people on the edge of the painting. The two women standing and looking up to Bosco in adoration might be the mother and sister of the boy. These dress is animal skin like though worn in a more ‘European’ fashion that in previous images, i.e., it appears cut to fit in a way other skins weren’t, they were just thrown over a shoulder.

The boy kneeling and in rags might also be a relative of the boy with the book but he is still outside the pale of the church, hence his lowly and marginal situation.

Here we see that the only true way for the indigenous people to advance is to give up their old ways, their old traditions and religions, including their own dress. So there’s no respect paid by the Catholic Church to those old traditions, only the supplanting of them by the cult of Christianity.

Cathedral, Bariloche, Argentina

It might seem a little perverse to be going into Argentinian and Chilean churches looking for ‘proof’ of how they might speak well of the indigenous peoples but that doesn’t reflect reality nor does it reflect how those people have been represented in the art that decorates those churches.

This is the most substantial of the churches I’ve visited so far on this journey, the ones in southern Patagonia being oft times little more than corrugated iron shacks, although big shacks. This one resembles more of what Europeans would recognise as a Cathedral, although falling into the category of a small one.

It is relatively recent, being completed in 1946 but having undergone some major work in the last decade or so. That’s an important date to bear in mind as it shows that these racist and generally disparaging attitudes to the people who were here before the Europeans is really being brought into the present.

A statue here, or a painting on a cupola there can be put down to attitudes and thinking of the past – an argument that I don’t accept but will let it stand for the sake of argument. However, that argument falls down when we are dealing with a couple of stained glass windows, as is the case in the Bariloche Cathedral.

There are a lot of stained glass windows in this building and they don’t come cheap. Most of them are of the general, generic story from the Bible, of the life of Christ etc., etc., etc. Boring really but two of them are different. I’ve seen countless images of Christian Martyrs before but these two are different as they fit into my argument that the Catholic Church, has, is and will always put the interests of itself before the interests of any marginalised group in society. That marginalised group in this case is the indigenous population of Patagonia.

Nicolas Mascardi – Bariloche Cathedral

This is an image of a priest, in whatever danger he might be not be able to let the crucifix fall from his grasp as he holds it close to his chest, in his left hand, even though he might be in his final death throes. He is being attacked by two aggressive males. As they are ‘indios’ they are naked from the waist up and wear only a simple wrap around skirt. Around their foreheads they wear a band and have long hair. Even the depiction of the hair length is important as long hair for Europeans, at the end of the 19th century and into the 20th was not common and would put you outside the pale.

They are bare footed (of course) whilst he is wearing shoes, the product of European civilisation. Both of them, one in his right hand the other in both hands, hold what could be a wooden club (we don’t see the end but that’s what it appears to me) ready to crush the life out of the priest whose only fault was the wish to bring the truth of the Lord to the ignorant savages.

(It might be worth remembering that when Pinochet led the September 11th 1973 coup against the legally elected government of Salvador Allende it was long hair that condemned many young males to imprisonment and eventual murder in the Santiago football stadium.)

On the other hand the priest, Nicolas Mascardi, is dressed as would a 17th century representative of the Catholic faith. For it was on 15th February 1674 that Mascardi met his maker – and achieved what he was after all the time, martyrdom.

The mountains of Patagonia are in the background and surrounding the scene of the murderous attack are the plants that are found in the region. On the edges of the main image are depictions of the ‘bolas’ – the weights connected to long rope which the ‘savages’ used in hunting. So here we have a reinforcement that the perpetrators were not civilised.

On the ground, having falling from Mascardi’s hand in the violent encounter, lies an open book where we can read the words, in Latin, ‘For the greater glory of God’.

At the bottom of the panel are the words: ‘Martir, IC, DL, R.P Mascardi’ – Martyr, ??, ??, Padre Mascardi’.

Below all, in the middle of a blank, white scroll is the national symbol of Argentina, two bodyless arms holding a stick from either side upon which is a red peasant’s cap. (A strange national symbol but it seems that in the 1830s the new independent state of Argentina needed a symbol and that one was available.)

The second is of another priest on the point of martyrdom. This time Padre Poggio. This looks like a Mission is being attacked (Mascardi was treacherously attacked while alone in the countryside). Buildings are on fire and smoke is everywhere, there are even flames and smoke in the chapel, where a table knocked over gives the impression of the chaos caused by the attack.

Poggio – Bariloche Cathedral

The ‘indios’ are dressed the same as in the previous stained glass window. One of them, outside the chapel, is just about to club to death one of the faithful. Another, who we see in full, is just about to plunge a spear into the chest of another of the faithful who is falling over in his attempt to save the Mission, the chapel and the priest.

Throughout all this chaos Padre Poggio remains calm, resigned to his fate he is on his knees praying to an unseen crucifix. The altar remains intact and clean. There’s a golden chalice sitting upon the white, embroidered cloth behind which an open book has the single word ‘Oreimus’. To complete the tableau a candle burns in a candlestick on the right of the altar.

Poggio is from a later era. His clothing is a large white vestment and on his left shoulder is the symbol of the Argentina.

Likewise with Mascardi has the words ‘Martir, IC, DL, P Poggio’ – Martyr, ??, ??, Padre Poggio’ and the Argentinian national symbol below all.

Both these windows can be found on the left hand side of the nave, looking towards the altar.

It might be said that these images reflect a past which has changed (but an expensive past, stained glass windows of such complexity don’t come cheap) but that’s not the case. In the Cathedral there’s an exhibition which includes the names of 5 ‘martyrs’ from the 17th and 18th centuries. Mascardi appears there but strangely, as he merits a window, Poggio is not.

So, for the Catholic Church and those active in the faith in Bariloche the fate of these priests still has resonance.

The problem with this situation is that there is an overwhelming stress on the importance of the Europeans, a Eurocentric (or perhaps now ‘western centric’) approach to other countries and peoples, that Europe is always right. If these same ‘indios’ had arrived in Europe and had attempted to convert the people there to their religion those who opposed that would have been seen as heroes and would have had stained glass windows commissioned in their honour – in the event that the invasion had been defeated.

But when the indigenous people of the Americas, both north, central and south, tried to do the same to protect their homes, their lifestyle, their culture and religion they are seen as being murderous savages.

Is there any point in saying more?