Ek’ Balam – Campeche

Location

This site is situated on the north-eastern coastal plain of the Yucatan Peninsula, where the topography is sedimentary rock that formed in the Cenozoic period, 63 million years ago. Nearly all the terrain is flat, with a few elevations in the south rising to a maximum height of 210 m. There are very few sources of surface water and the phreatic water table is situated between 20 and 25 m below the ground. However, there are numerous large underground aquifers, as well as several cenotes in the area; two of these are fairly large and situated at the east and west ends of the core area, approximately 1 km apart. There is also a large quantity of funnel-shaped depressions, known as k’op in the Maya language and doline in English; although usually dry, they can store water during the rainy season. In some cases they have a diameter of up to 100 m and are 17 m deep, nearly reaching the aquifers, and for this reason the ancient Maya excavated wells at the bottom of them. The site must have obtained its water supply from the cenotes and sinkholes, storing rainwater in the chultuno’ob (underground artificial cisterns) and other types of tanks. The climate in the region is of the hot, sub humid variety, with the rain falling mainly in the summer months. The average temperature is 26° C and the annual precipitation is usually at least 1,200 mm.

The archaeological site is situated approximately 190 km from the city of Merida. The path is well signposted. Take the Tizimin road from the city of Valladolid, drive through the town of Temozon and 7 km further along the road join the 5-km road leading to the archaeological area.

Pre-Hispanic history

According to data from the first investigations at the site, conducted by an American team, Ek’ Balam was occupied from the Middle Preclassic to the colonial period (from AD 600 to 1600). During the explorations carried out as part of the INAH Ek’ Balam Project, one of the sub-structures of the Acropolis furnished the earliest example of architecture, dating from the Late Preclassic (c. 300 BC-AD 300). Ek’ Balam experienced its heyday in the Late Classic (c. AD 770-896), during the reign of Ukit Kan Le’k Tok’ and his descendants. In the Postclassic, changes occurred for reasons that we have not yet determined and no more large constructions were built, giving way to small adoratoriums, platforms and altars. Ek’ Balam continues to be inhabited to this day, and although the most important constructions are partly in ruins, they are used for ceremonial purposes. For example, an altar has been built on the collapsed Ball Court, and offerings are even deposited in the rubble of certain structures, such as the East Hieroglyphic Serpent and the south-east corner of the Acropolis. This means that the Walled Enclosure continues to be regarded as an important sacred space. The occupation of the site continued in the 16th century and there is a colonial settlement situated north-east of the core area with the remains of an Indian chapel.

Little is known about its origins as most of the information we have comes from the Late Classic constructions. However, its long history dates back to the Preclassic and its continued existence to colonial times, marked by different stages of occupation and development. Its golden age has furnished important information about its architecture and artistic development, and also about its governors, who forged the magnificent Talol empire. One of the most significant pieces of historical evidence is the existence of the emblem glyph, which means ‘sacred king of Talol’ and which has confirmed both its nature as a kingdom and its name, associated with that of King Talol. Although that was the name of the kingdom (and its meaning has yet to be deciphered), the capital was Ek’ Balam, which means ‘black, or bright star, jaguar’. The first king associated with the emblem glyph was Ukit Kan Lek Tok’, the second K’an B’ohb’ Tok’, the third Ukit Jol Ahkul and the fourth K’inich Jun Pik Tok’ K’uh…nal. The name of another governor, K’ahk’al Chu, has recently been found but there is no date associated with it so we do not know where it fits in with the others.

Site description

Ek’ Balam occupies an area of 15 sq km, but its core area is a walled enclosure containing over 40 buildings, mainly situated in the North and South plazas.

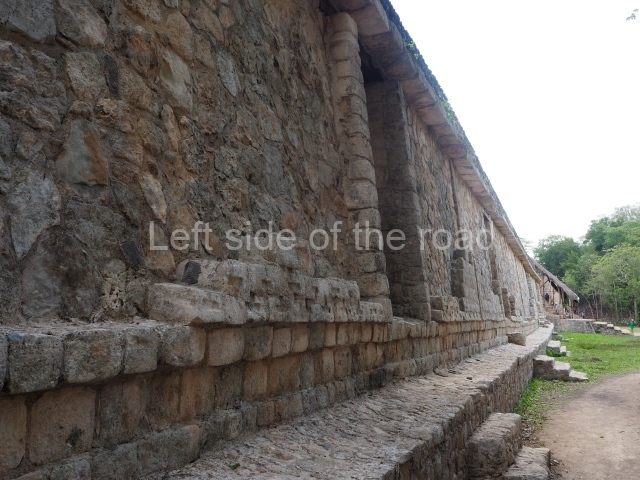

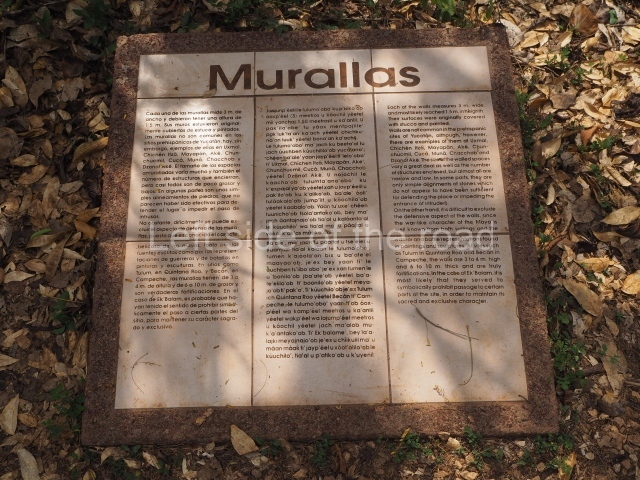

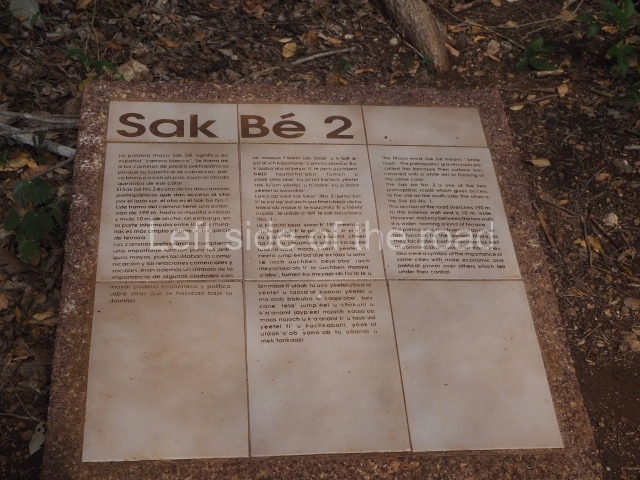

The walled enclosure occupies 1.25 sq km and is surrounded by two concentric stone walls – called Exterior Wall and Interior Wall – relatively low in height but originally with high wooden palisades. There is a Third Wall which connects some of the main buildings and during pre-Hispanic times provided greater protection to the royal seat. Five causeways or sacbeob once departed from the Exterior Wall to other parts of the city, and one of them even appears to have led directly to another city. Two of these causeways are situated on the south side and the remaining ones at the other cardinal points and the ramp of Structure 8 furnished an important offering of more than 90 vessels and numerous burnt stone balls. Structure 9 contains a partly concealed room with a stucco-modelled frieze painted in blue, black, green and red; the scene depicts an important personage in profile, seated on a throne and holding a bird in his hand. During the excavations, the ring of Structure 8 was found but unfortunately the ring from Structure 9 was stolen many years ago. The last stage of the Ball Court was built in AD 841, as evidenced by a painted capstone bearing this date and the name Tz’ihb’am Tuun.

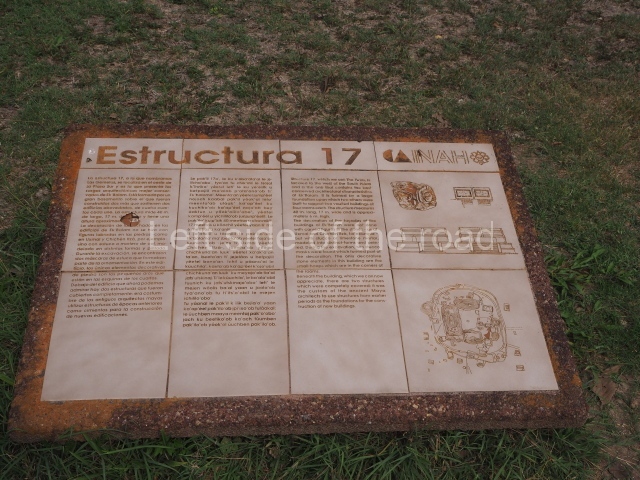

Among the grand constructions in the north plaza are several smaller structures, including Structure 4, composed of a group of altars and a steam bath; several tiny temples were also found, such as structures 5, 7 and 21, and a platform-altar at Structure 6. These can only have been used for depositing offerings because they are too small for any other activity.

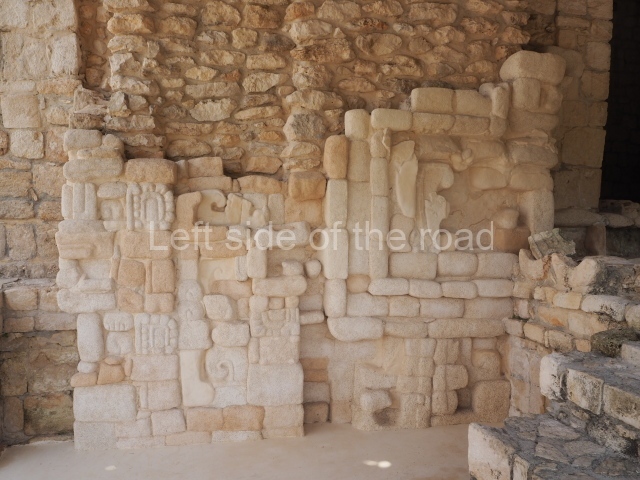

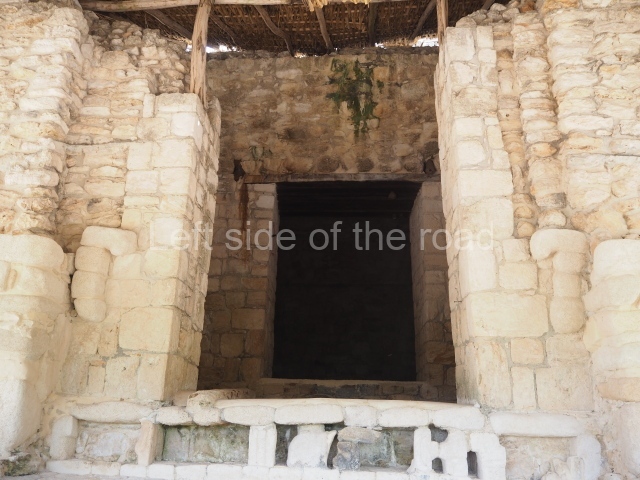

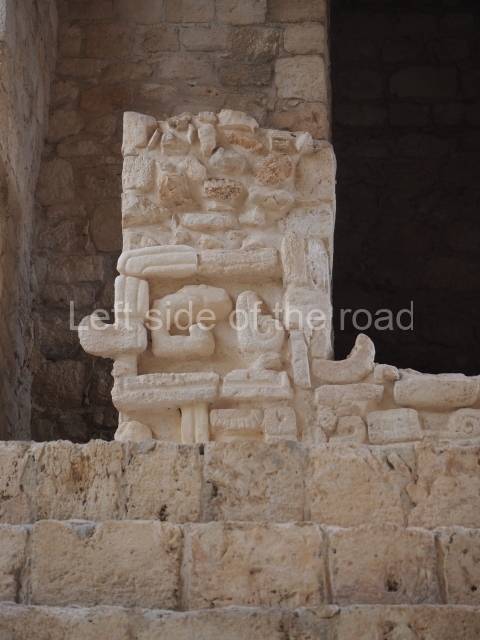

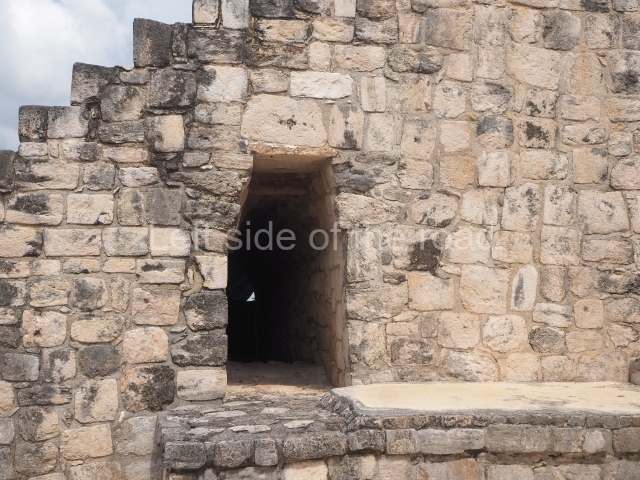

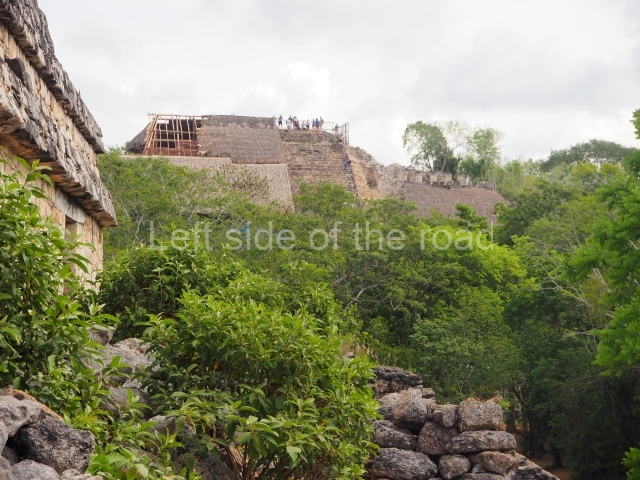

The North Plaza is the largest and oldest at Ek’ Balam and is distinguished by three large constructions numbered 1, 2 and 3. Structures 2 and 3 have not been excavated, but Structure 1, known as the acropolis, has been undergoing excavation and restoration works since 1997; this large construction is 160 m long, 60 m wide and approximately 31 m high. It is a vast and complex volume with numerous superimposed construction phases; it contains countless vaulted rooms, distributed on six tiers and connected by numerous stairways and passageways. On the fourth tier, the facades are profusely decorated with modelled stucco; one of the motifs represented is the face of a mythical creature, the earth monster, which for the ancient Maya symbolised the entrance to the underworld. The central facade is distinguished by the imposing monster-mouth entrance surrounded by fangs, which ‘devoured’ or ‘spat out’ those who entered or left the construction. Known as the Sak Xok Naah de Ukit Kan Le’k, ‘the White House of Reading’, the bowels of this building also provided shelter for the mortal remains of the founder of the ruling dynasty during the Late Classic. The offering accompanying his burial contained 21 vessels, some made of clay, others of alabaster, as well as 7,000 objects of shell, jade, bone and other materials; some of these were very rare, such as a gold earring in the shape of a frog and three pearls.

Monuments and ceramics

Stelae 1 and 2 were the only such monuments found inside the walled area; another stela was rescued from a nearby bank of materials but it was not erected at the site during pre-Hispanic times. Stela 2 is greatly eroded, but Stela 1 displays beautifully carved bas reliefs of two governors of Ek’ Balam; the one at the top is Ukit Kan Le’k, represented as a deified ancestor. The principal figure is a king who erected his stela on 18 January 840 to commemorate his coronation; the name is eroded and nowadays only partly legible: ‘… K’uh Nal ….’

The Hieroglyphic Serpents commemorate the construction of one of the stages of the Acropolis and represent the open mouth of a serpent whose forked tongue ‘descends’ the steps. According to the inscription, the stairway is called Win Uh and was built by Ukit Kan Le’k Tok’, the sacred king of Talol. Numerous stone and stucco sculptures have been recovered at Ek’ Balam, but most of them are incomplete and much deteriorated. Nevertheless, a few of them display traces of paint and fascinating details corresponding to personal garments and adornments.

A large number of utensils and ceremonial objects have been found at Ek’ Balam and shed light on the activities, customs, beliefs and trade with other regions. The materials vary from stone, bone, shell and metal to clay; the latter is a crucial find because it establishes the timeline of the site and its relations with the other peoples with whom it traded such materials.

Importance and relations

Ek’ Balam is situated at a geographical point at which no other pre-Hispanic site of such scale and characteristics is known, and it therefore fills a geographical and temporal void between the domains of Coba and Chichén Itzá. We now know that the four kings of Talol that have been identified governed for an approximate period of 100 years, from AD 770 to 870, and were responsible for the kingdom’s prosperity. This interval of time matches exactly the decline of Coba, around AD 770 and the flowering of Chichén Itzá around AD 860. Ek’ Balam coexisted with both sites at different moments in time and undoubtedly maintained a different type of relationship with each of them, which we are currently trying to confirm. Much of its importance lies in its distinctive architecture and decoration, which display an interesting mixture of characteristics from other regions in the Maya area, such as Peten, the Puuc region, Rio Bec and Chenes; this principally affects Building 1 or the Acropolis, whose exquisite and well-preserved facades are unique in the Maya area.

Leticia Vargas de la Pena and Victor R. Castillo Borges

From: ‘The Maya: an architectural and landscape guide’, produced jointly by the Junta de Andulacia and the Universidad Autonoma de Mexico, 2010, pp417-421.

1. Exterior wall; 2. Interior wall; 3. Sacbe 1; 4. Sacbe 2; 5.Structure 18; 6. South Plaza; 7. The Oval Palace; 8. The Twins; 9. Structure 14; 10. Ball Court; 11. North Plaza; 12. Acropolis; 13. Structure 2; 14. Structure 3.

Getting there:

From Valladolid. Colectivos leave from Calle 37, between 44 and 42. M$70. To return you need four passengers, which might mean a long wait at the archaeological site combi stop – or you could pay for four seats. If you can organise a group of people going at the same time it would make life a lot easier.

GPS:

20d 53′ 10″ N

88d 08′ 12″ W

Entrance:

M$531