Ukraine – what you’re not told

Mary Barbour and the 1915 Glasgow Rent Strike

Introduction

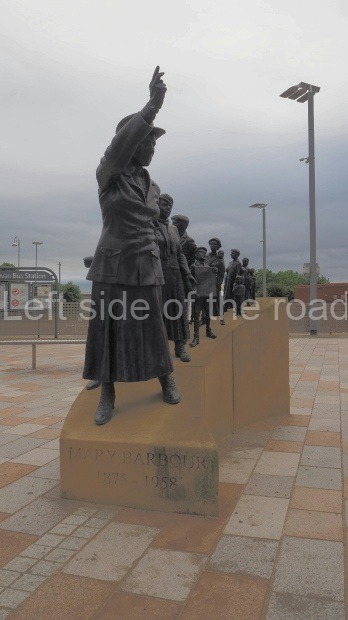

A sculpture commemorating the 1915 Glasgow Rent Strike and one of its female leaders, Mary Barbour, was unveiled on International Women’s Day, March 8th 2018. It can be found in the square in front of Govan Subway Station on Govan Road, Glasgow. It’s the work of sculptor Andrew Brown who won in a competition of five shortlisted entries.

There are many examples of Socialist Realist Art posted on this blog, mainly from Albania but also some from Georgia and the erstwhile Soviet Union. There are, in various parts of the UK, statues and monuments that seek to commemorate working class struggles of the past. There’s not that many but there are a few.

One of the finest is the monument next to the Pierhead in Liverpool. It was originally commissioned to commemorate those men in the engine room of the Titanic who kept the generators running to the very last minute – although they were sealed in and had no chance whatsoever of escape. However, before it was completed the First World War (when workers and peasants fought each other for the benefit of their masters and their respective country’s imperialist ambitions) intervened and so the monument was re-titled ‘To the Heroes of the Engine Room’, meaning all those below decks engineers who died in Naval and Commercial shipping between 1914 and 1918 – as well as those engineers from the Titanic.oo

But Socialist Realist Art needs the workers to be actually involved in the struggle to make a new society if it is to merit such a description. Art that represents workers’ struggles in capitalist societies merely do that, represent a moment, even in the past. It has little more to say. And sometimes instead of actually commemorating the past they just go to demonstrate how matters have not changed.

That’s one of the problems (but not the only ones) with the Mary Barbour statue in Govan. It was inaugurated more than a hundred years after the event it commemorates yet in Glasgow, as in the rest of the UK, the dire situation of housing for millions of people is only slightly (but not much) better than it was in 1915. The workers of Glasgow were facing exploitative landlords who were making even more money due to the very fact that the country was involved in what was to become the first really global conflict. Speculation in housing in early 21st century Britain is rife and its the workers who have to face the consequences.

Profiteering during wartime is not new – and the war of 1914-1919 wasn’t the first where that had happened. And we only have to look at the almost unimaginable amounts of money that have been made out of the disastrous conflicts of the last 20 years – in Afghanistan, Iraq, Libya, Syria and Yemen – to see that it goes on to this day.

One of the important aspects of Socialist Realist sculpture is the relationship that those depicted have with each other. What is the power relationship, what is the hierarchy, where is the unity and equality of the efforts of those being celebrated?

And it is this relationship in the statue in Govan that is the most disturbing.

The statue

I would be one of the first to argue for leaders, both as individuals as well as organisations and parties. But what is the relationship here?

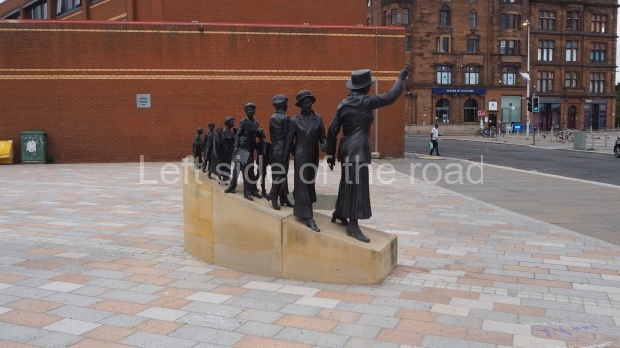

Brown has depicted Mary Barbour as at the head of a group of people taking part in one of the many marches that occurred at the end of 1915. However, I have not seen any photo were Barbour is physically at the head of the column of marchers. In fact, most photos seem to depict more of a melee rather than an organised march. Brown has interpreted Barbour’s leadership role in the struggle as being at the front.

Now we have to assume that the idea that is represented by the figures getting smaller as the sculpture moves further away from the woman at the front is to give the impression of the large amount of people who would have been on the streets at the time of the biggest mass gatherings outside local government and court buildings – the idea that parallel train lines ‘merge’ the further they are away from the viewer.

However, by using this device he has also introduced a change in attitude of his subjects.

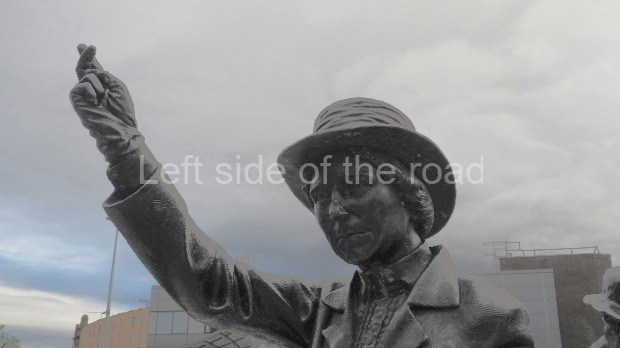

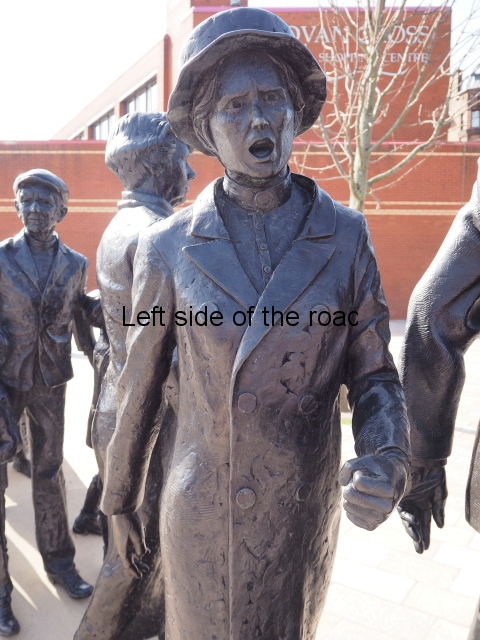

At the front Barbour is ‘respectably’ dressed in a fitting overcoat – as befits a leader. She wears a smart hat and her hair is immaculate – what we can see of it. She is depicted striding forcefully ahead, hand raised in confrontation with the authorities. She knows were she is going, knows what she wants and is determined to get it. But as we move to the back of the statue the characters become more downtrodden, they hang their heads in despair, the looks on their faces is one of desperation and not determination.

Immediately behind her are two women, both also similarly ‘respectably’ dressed, slightly smaller, and probably supposed to be a helpers, lieutenants, of the real leader. (Or they could also be supposed to represent some of the other women in the leadership of the struggle, but not as important as Mary Barbour.)

The first, who is not looking in the direction of ‘march’ but to her right, wears a long overcoat over a fashionable dress (the decoration showing through the open coat just below her neck). The dress extends below the overcoat. On her head she wears a fashionable floppy hat with a wide brim and embroidered decoration. On her feet she has very smart, pointed shoes or boots. She shows her determination in a couple of ways. Her mouth is open as if she is shouting her opposition to the police, sheriffs and bailiffs and her left hand is clenched into a fist.

The second wears a smart fitting jacket with a tailored skirt and although she is bare-headed she wears a long woollen scarf around her neck to keep her warm from the winter cold (things came to a head in November). She also walks in a more elegant manner, her hands away from her body and her fingers apart.

But as we go further back the state of dress becomes more shabby, more neglected. The women wear threadbare caps or scarves tied under their chin. Some have no hats or head coverings at all – the really poor. The same goes for the footwear. These aren’t leaders as they don’t dress the part.

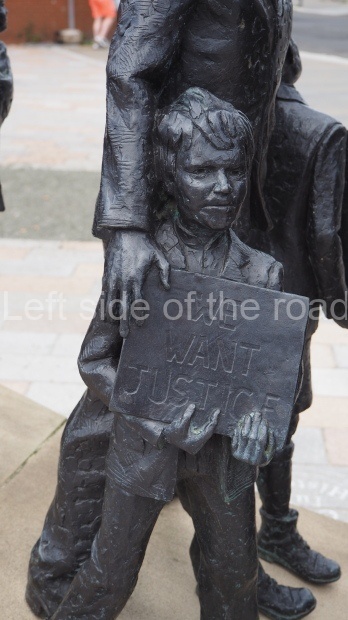

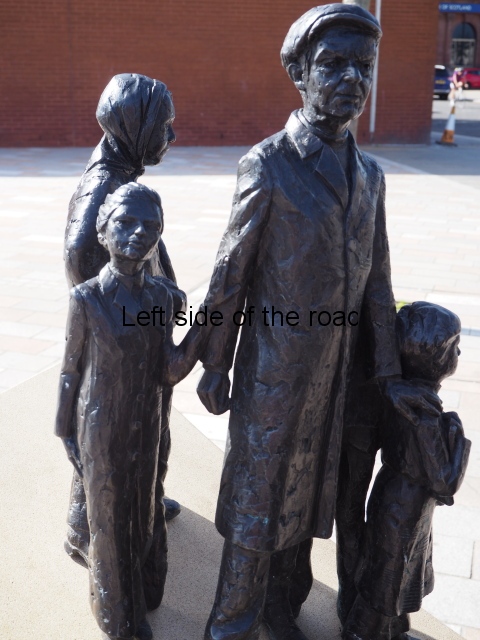

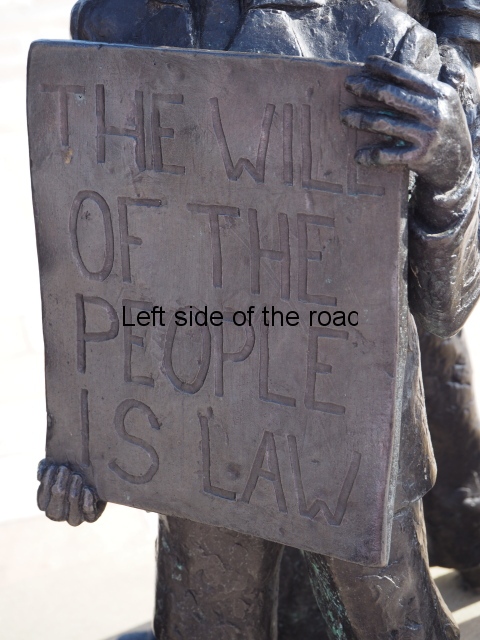

Next comes a group of three, a old man (we must remember this was at a time of conscription and if not in one of the ‘protected trades’ all young men would have been in the slaughter fields of the Western Front or some other hell hole in more far flung locations) and two young boys. He has his right hand on the shoulder (also touching the placard) of the boy on the left, the younger of the two. The other child is leaning against the left side of the man, presumably their grandfather. The depiction of children in these marches, demonstrations is accurate as can be seen by photos of the time. Both these boys are carrying placards, the one on the right saying ‘The will of the people is law’ and the one on the left ‘We want justice’.

Next is a group of three, but this time female. On the right is an old women who seems to be bearing the woes of the world on her shoulders as well as the babe in arms she carries in her left arm, wrapped in a large shawl. Her clothes are makeshift, wearing whatever (possibly all) she had to combat the cold of a Glasgow winter’s day. She also wears a wide-brimmed hat but it’s a not a fashionable copy of the one worn by lieutenant number one, being without decoration.

Next to her is a young teenage girl. She’s wearing what would have ben quite fashionable for a young working class girl at the time – a short cropped jacket. This is worn over a long dress, the standard of the time. She has a scarf on her head, tied under the chin in a rather large bow, presumably also the fashion for young girls of her age. But however fashionable, or not, these two women show their roots by their footwear. They are both wearing functional but not very fashionable heavy and durable shoes – compare with the three ‘leaders’ (whose footwear, incidentally – to again show them different from the hoi polio – have high heels).

Next in line, and as has been the case so far, slightly smaller in size, is a group of four – an old man (again above conscription age and probably the grandfather) with two young boys on his left and a young girl (probably just pre-teen) on his right. The two boys seem to be stuck to him like glue as they are pressed right up against him.

The boy who is the youngest of the children is carrying a placard with the slogan ‘Justice for all’. His older brother, who is pressed against his back as well as the thigh of the grandfather, seems to be more interested with what is happening behind the group than where they are going. The girl on the old man’s right is the oldest of the siblings and she is depicted in a charming manner as her left hand rests on the right sleeve of her grandfather, too old to be holding hands but too young to be totally separated from him.

They are all reasonably dressed, especially the young girl as she wears a very long overcoat, with large buttons on the front and a high necked shirt, the collar of which we can see behind the turned back collar of her overcoat. She has her long hair tied back in a bun and wears nothing on her head, as do her two brothers. The old man wears a flat cap.

Bringing up the rear is the most desperate of the whole procession, this is a group of four – a women (who really looks like she has suffered all her life) with her three children. The two on her left are in a strange combination. The oldest boy is holding his baby brother/sister in his arms but the two of them are then wrapped in the same large shawl that passes around their mother – sharing body warmth as well as the protection provided by the shawl.

They look the poorest of the statue as although they are all wearing decent clothes and shoes they don’t have enough to pay for an overcoat that is necessary in a Glasgow winter. The only one that has anything on their head is the mother who has a large scarf over her head tied with a large bow under the chin – as did the teenage girl earlier in the procession. The final figure of the ensemble is a young boy who is slightly away from his mother but also more interested in what is happening behind the group than the direction it is moving.

The Plinth

The group, which is made of bronze, is standing on a sand coloured concrete plinth which gets higher as it curves at the back as the characters get smaller, extenuating the idea of distance between the ones at the front and those at the back.

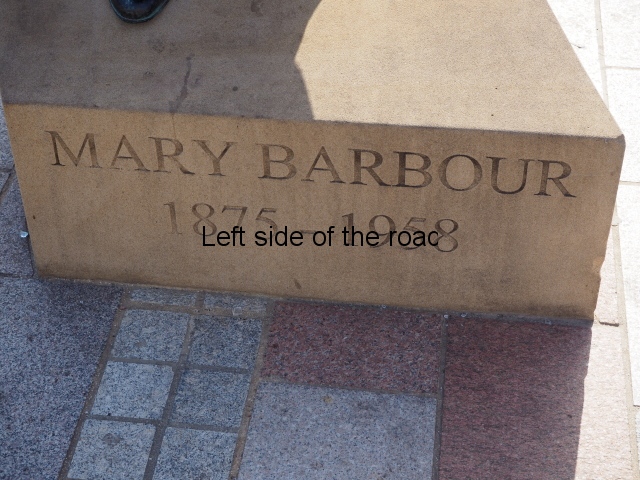

On the very front of the plinth, under her feet, is the name Mary Barbour and the dates 1875-1958.

History and staues

But that’s the only information provided. And that’s one of the problems when statues are erected in many capitalist countries – most people don’t know why. Statues do become a point of focus in certain circumstances but if everything is without conflict then any new statue might cause a short amount of discussion (e.g., the Mary Wollstonencraft statue in London) but it is soon forgotten.

Obviously there are times when statues become the centre of focus of a particular event or political situation. Presently there’s controversy of the statues of those who were related to the African slave trade, both in America (where a number of Confederate statues and monuments are being taken down) or in the UK when the statue of Edward Colston was pulled off its plinth in Bristol and dumped in the docks.

But that ‘debate’ which has been promised, in pre-revolutionary circumstances, will only go so far. Horatio Nelson was a prominent supporter of the trans-Atlantic slave trade but it’s unlikely he will be deposed from his dominant location in London’s Trafalgar Square. And other statues of British pro-slavers will remain throughout the country because people, in general, don’t know they exist.

It’s a sad fact that British people, at least, have a poor concept and knowledge of history and the placing of this statue is a case in point. When I first saw the Barbour statue it had been in place for over a year yet whilst I was taking photos I was approached by a local woman who asked me who it was and what is was all about. A Sassenach had to explain her history to a local, Govan woman.

So a plaque somewhere in the vicinity would not go amiss.

Brown reproduced the placards from those that were on the streets at the end of 1915 – so are authentic in that sense. However, a placard that also appeared in a number of newspaper pictures was one with the slogan ‘My father is fighting in France and we are fighting the Huns at home’. This just goes to emphasise the climate in which this dispute took place.

(For many the war (that was starting to take a dark turn) was still a patriotic affair – this was the case even though many of the leaders of both the Rent Strike and other industrial disputes in Glasgow at the time were Communists and members of the various groupings that were later (under the instigation of VI Lenin) to form the Communist Party of Great Britain in the early 1920s. Many of these activists were against the war as an imperialist war where the workers were fighting and dying for the imperialist interests of their own ruling class – but this was not necessarily the case with a majority of the working class.

Although attitudes to the war changed in the next couple of years when Lloyd George’s promise of ‘Homes fit for Heroes’ became, very quickly, just mere words and the whole of the UK was plunged into the deprivation of the 1920s, there was still a reluctance on the part of the workers to ditch the ‘patriotic’ stance and make previous promises a reality.

More than a hundred years later that’s still the case – as is shown by the chronic situation of housing and the impossibility of the problem being resolved under capitalism.)

But if there was a reason for including the derogative ‘Hun’ in the placards of the strikers in 1915 there’s also a reason, in the climate in the second decade of the 21st century, NOT to make reference to the word on a public statue – a change in sensitivities.

History and background of the 1915 Glasgow Rent strike

For more information on the history and background to the strike you’ll get some reasonably good information on the links below. Unfortunately, some of the sites are Trotskyite but as they had no presence at all in 1915 Glasgow all they can quote are Labourites or Communists who were either in the leadership of the rent strike or were shop stewards and union representatives in the Clyde shipyards.

Some of these articles contain interesting archive photos of the struggle.

1915 Glasgow Rent Strike: how workers fought and won over housing – a reprint (published on the centenary of the strike) of an article produced on the occasion of the Fiftieth anniversary in 1955.

Mary Barbour & Rent Strike 1915

Trish Caird looks at the life of Mary Barbour, leader of the 1915 Glasgow Rent Strike – a movement that was principally led, organised and executed by women

Our Housing Heritage: How Glasgow tenants ‘fought the huns at home’ during World War One

as well as an article that seeks to find inspiration from the past struggle to address the current crisis in housing in Glasgow

We need spirit of Mary Barbour to reform rents

Ukraine – what you’re not told

I have to admit, and I do mean this respectfully, but I find this critique of the Mary Barbour monument a bit bizarre. You might want to actually speak to the people of Govan about what the statue means and why it was installed (or even do a quick social media search…you’ll find lots on Barbour’s monument). Most important to understand is that it was never intended as ‘Socialist Realist Art’, and it was a commemoration of Mary Barbour, not the Rent Strike (though Brown did choose to depict that; not all of the maquettes did). You might also want to learn a bit more about Barbour’s history; what she accomplished as a politically active working-class, rather than middle- or upper-class socialist woman; and what she meant and still means to the Govan community. Heck, maybe even learn a bit more about Glasgow and Scotland while you’re at it, if you are truly interested in the art. La Pasionaria would be right up your alley. You are of course entitled to your opinion, but I would just encourage you to first make sure your opinion is informed.

Once a piece of art is placed before the public the artist loses the right to determine how that piece of art is interpreted. The context of the art is important, and in this case it’s the Rent Strike of 1915. As the artist (who won the competition) decided to include reference to that struggle in his work the fact that the initial idea ‘was a commemoration of Mary Barbour’ ceases to be primary. It seems from you statement that you would have preferred one of the other submissions to have been selected, one that considered individuals as the prime movers in society. That would be following the tradition of the many hundreds of statues that litter the streets of Britain ‘celebrating’ those who ruled over the majority and with the implication that we should be grateful for what they did – even, supposedly, the slave traders. You suggest that all of Govan is aware of Barbour ‘and what she meant and still means to the Govan community’. However, I was only there for a matter of minutes but even during that short time I was asked, I assume by a ‘local’, what the statue represented – as I wrote about in my post. Perhaps if people were made more aware of the mass struggles of the past, rather than a select few individuals in temporary positions of leadership, we might realise that those mass struggles are what we need to revive to solve the issues of the present.