Impressions of Saranda, Southern Albania

At one time a quiet port in the south of the country, the Albanian town of Saranda gets the Benidorm treatment.

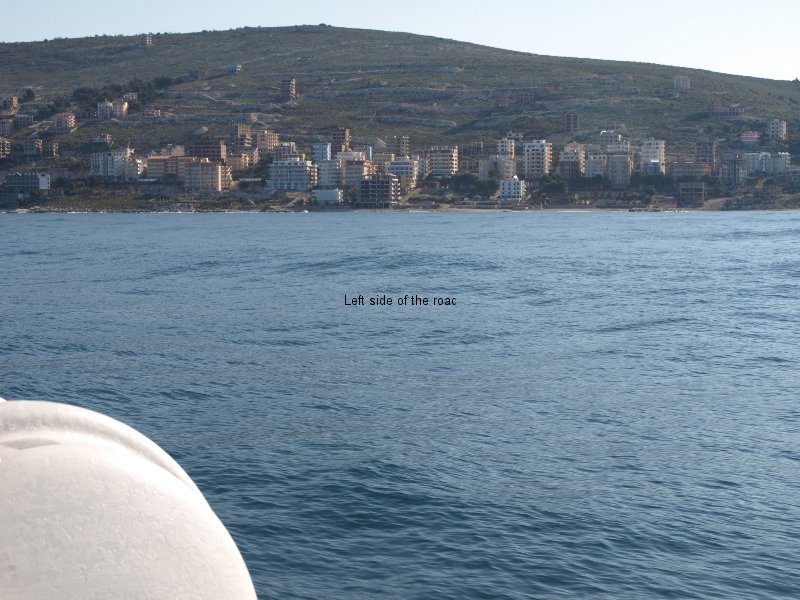

Saranda is one of the few towns where you can arrive from another country by easy, quick and readily available public transport, i.e., the fast ferry from Corfu, Greece. When I first made that journey I was looking forward to seeing a small town from the sea but the closer you get to your destination you see that ‘progress’ has already made its mark on the town.

Like the rest of the world the town is in the mad dash for the tourist dollar/pound/euro/leke, you name it they want it. This has meant that over recent years there has been a rapid increase in construction and this has been done in a seemingly unplanned manner. Or if there is planning there are few attempts to maintain what would have been the charm of the small Mediterranean sea port.

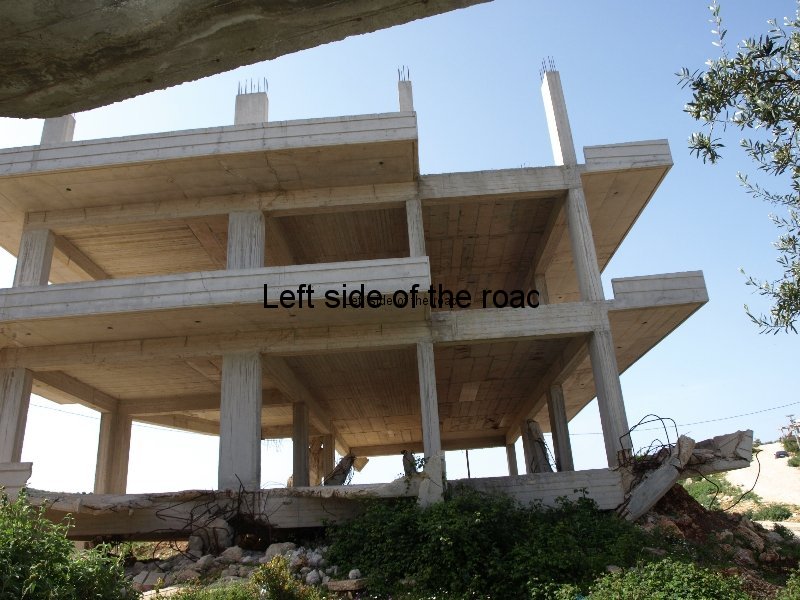

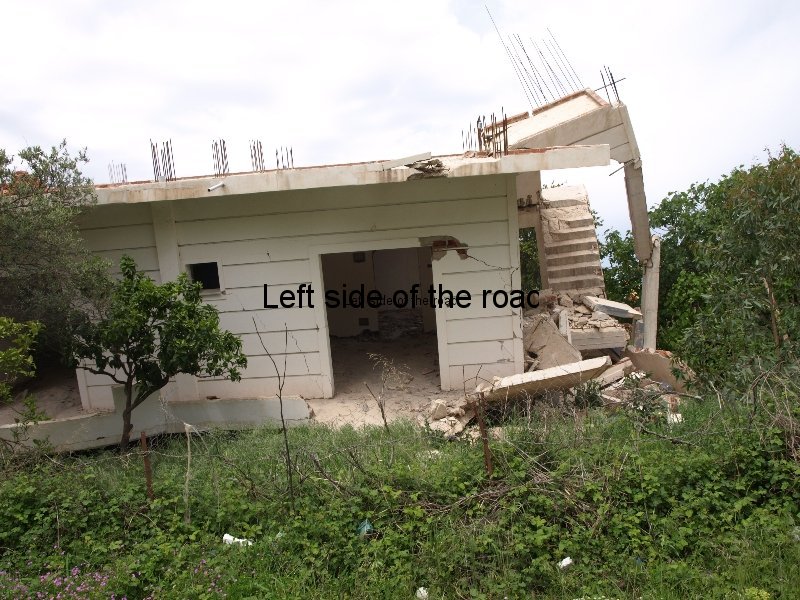

From the sea you are aware of the buildings slowly creeping up the high hills that confine the town along a narrow stretch of coast. One of the problems is that many of these are incomplete, with little sign that the buildings will ever be completed. Many of them appearing on the slopes are obviously after a space where no one is able to build in close proximity to spoil the view across the Ionian Sea towards Corfu. This includes constructions that sit on or close to the summit of the hills, something which other Mediterranean countries are starting to make illegal as it spoils the look of the countryside.

Although there doesn’t seem to be the same reaction to illegal/unplanned/spontaneous construction in Saranda as in Ksamil the blot on the landscape is even greater. This is even more evident along the road which heads south from the town towards Butrint and the Greek border. But this explosion in construction is also taking place in the centre of the traditional town.

Here the new construction has had the effect of basically ‘hiding’ the old town from any visitors, perhaps not on purpose but certainly as a consequence of the mad rush to turn the town into a popular tourist destination. And this small area that remains untouched (but for how long I don’t know) is only a 2 or 3 minute walk from the town’s main square.

Obviously developed in a time before the level of car ownership that now exists the area is a relatively quiet and pleasant oasis, although some drivers will try to get up any road, however narrow and however low their driving ability. But it does offer an insight to what the town would have been like 20 to 30 years ago. The houses seemed to be relatively self-contained in that many have gardens and if you pass by at the right time of year you will be welcomed by the smells from the orange blossom, the smell of ripening figs or just the scent from jasmine and a whole variety of herbs, so different from the almost sterile area alongside the seafront promenade.

And remarkably free of litter. The random dumping of rubbish is a real problem throughout Albania but I got the impression in these few streets that there was an element of pride in the neighbourhood, unfortunately lacking so often, and you’re not ploughing through piles of litter.

And an ‘introduction’ to the post-Communist resurgence of superstition.

Most writers of the guide book entries for Saranda seem to like the seafront, but I’m not so inspired. Bars and restaurants are being built over the beach (which is already very narrow) and denying any public access. There’s also an extremely adventurous (and I would have thought a bit pie in the sky) plan to develop this seafront/promenade area, with even an Olympic size swimming pool. Not, I think, in my life time.

Now a few ‘secrets’ not mentioned in any of the guide books, so a bit of a ‘Left Side of the Road’ exclusive!

If you’re into street markets there’s a daily market hidden away behind the buildings, a stones throw from the central archaeological square. With the sea at your back go up Rruga Vangjeli Pandi, the one beside the synagogue/basilica and effectively the ‘bus station’. Cross over Onhezmi and pass the taxi rank. About 50 metres on the left there’s a dead end road which seems to just go to a car park. Go up this a short way and then look for an alley way to the left, behind the new buildings on Rruga Onhezmi. This is the start the general market that’s open every morning, closing down at around 13.00/14.00. I’m not into such markets but for general bits and pieces is probably your best bet, although I’m sure you have to bargain (again something that’s not for me).

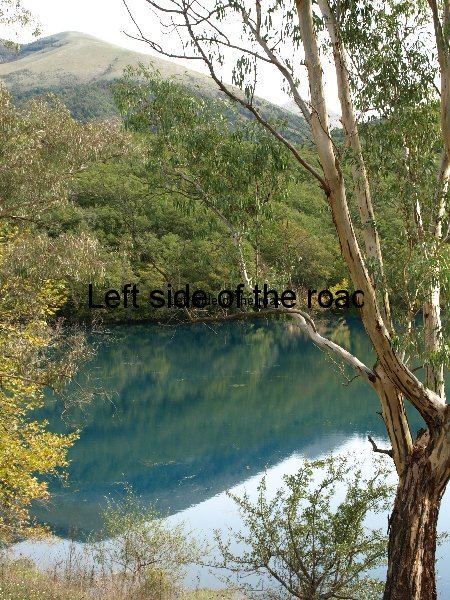

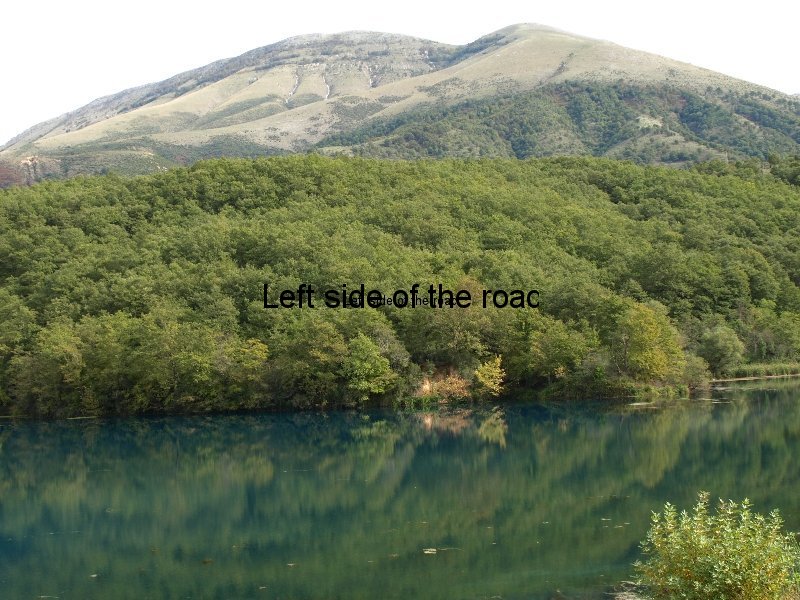

Also, if you are in Saranda when there’s a ‘r’ in the month and like mussels you can buy them from street sellers who congregate on Rruga Onhexmi, just above Central Park. The mussels have been cooked and shelled and are sold stuffed into what were once water/soft drinks bottles. I know this sounds dangerous, shellfish can really hit you for six if you get a bad one but this is where the restaurants get their mussels and the reputation seems quite high. They are good and come from the floating shellfish racks you see in the lake that’s on the left side of the road as you head towards Ksamil or Butrint. This lake is kept surprisingly clean when you compare it with other water sources throughout Albania not least, I’m sure, due to the value of the cultivated mussels.

Although I consider these mussels to be OK you have to make up your own mind about the risks. That’s my disclaimer.

The fresh food market is along Rruga Ionian, the street that runs parallel and closest to the coast. This starts to close down around 13.00/14.00. There are also a fresh fish stalls in the street. At the end of this street, by the huge tree in the centre of the intersection, is the bus stop for the bus to Butrint.

I hope that I don’t give the impression that Saranda is a place to avoid. It’s pleasant enough but not special for me and I don’t have the same approach to the place as other writers who might be more into holiday resorts, with their bars and street restaurants. It doesn’t, perhaps, help that my visits there have always been in the off-season, and that presents a different face to visitors.

Despite that Saranda is a pivotal place for visiting Ksamil, Butrint, Syri i Kalter (the Blue Eye), the Dema Monument, the small war memorial, and, at a stretch for a day trip, Himara and Gjirokastra.

The port is also the departure and arrival point for the fast hydrofoil ferry between Albania and Corfu.